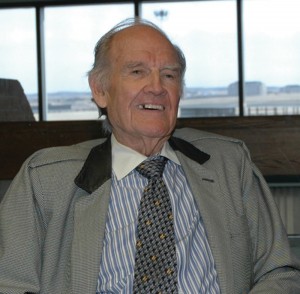

American As Apple Pie – George McGovern

Many contemporary Americans remember George McGovern in defeat. His loss in the U.S. presidential race in 1972 was fought in a terrible time in the country’s history. The late historian Stephen Ambrose painted a clearer image of the aviator, war hero and U.S. senator in his book, “The Wild Blue: The Men Who Flew the B-24s Over Germany.”

Many contemporary Americans remember George McGovern in defeat. His loss in the U.S. presidential race in 1972 was fought in a terrible time in the country’s history. The late historian Stephen Ambrose painted a clearer image of the aviator, war hero and U.S. senator in his book, “The Wild Blue: The Men Who Flew the B-24s Over Germany.”

McGovern was there in the skies over Europe during World War II, flying 35 combat missions in a sturdy B-24 bomber. His perilous missions earned the 21-year-old pilot the Distinguished Flying Cross.

McGovern first learned to fly in the Civilian Pilot Training Program. He took eight hours of instruction in a government-supplied, single-engine Aeronca before soloing on a windy day over Mitchell, S.D.

“Frankly, I was scared to death on that first solo flight,” McGovern remembered. “But when I walked away from it, I had an enormous feeling of satisfaction that I had taken the thing off the ground and landed it without tearing the wings off.”

In the fall of 1941, McGovern saw B-24 bombers for the first time at a local airport but couldn’t have imagined that he would soon be in command of one. In a matter of days, he had enlisted in the Army Air Corps and was sworn in at Fort Snelling, Minn. After basic and advanced pilot training, the Army trained McGovern to fly the B-24 Liberator in 1944.

In September 1944, McGovern was posted to the 741st Squadron based in Cerignola, Italy. The squadron’s mission was bombing Hitler’s oil refineries in Germany, Austria, Poland and Czechoslovakia. The boys of his crew decided that since he was the only married man on the ship, their B-24 should be named the Dakota Queen, as a tribute to his wife Eleanor.

Over the course of 35 harrowing missions against Axis military sites, McGovern and his crew braved terrible danger. His last mission might have been his worst. On April 25, 1945, the Dakota Queen joined all four squadrons of the 455th in an air assault on heavily defended Linz, Austria—Adolf Hitler’s hometown. The flak was intense, riddling the Dakota Queen and its crew with shrapnel.

To hear how George McGovern landed his crippled ship safely and returned to the U.S. to carry on a celebrated career in politics, read George McGovern Visits Airport Journals – By S. Clayton Moore

A Close Fraternity – Arnold Palmer

When Arnold Palmer was recently asked what he “never” travels without, he said, “Pete Luster, cell phone and golf clubs.”

When Arnold Palmer was recently asked what he “never” travels without, he said, “Pete Luster, cell phone and golf clubs.”

Clubs? That’s easy to figure out. The cell phone? He’s still an incredibly busy man. And Pete Luster? He’s the latest in a short list of chief pilots—a “good little fraternity”—who have shared the cockpit with Palmer. That list includes Charlie Johnson, who would go on to head Cessna, and Lee Lauderback, who’s made a name for himself at Stallion 51.

Arnold Palmer has spent a lot of time in the air, much of it in the left seat. The legendary professional golfer has about 18,000 flight hours. He spent time building model airplanes when he was a child, but credits an experience when he was 20 for his rekindled interest in aviation. While traveling on a DC-3 to an amateur golf tournament, the plane flew through a thunderstorm.

“There was a ball of fire rolling up and down the aisle,” he said. “I had no idea what it was. I thought it was all over.”

He would find out that it was an electrical phenomenon known as St. Elmo’s Fire.

“It was just static electricity,” he explained. “It released, and of course, nothing serious happened.”

That incident prompted Palmer to want to learn more about aviation. Later, when another friend introduced him to acrobatics, he vowed to learn to fly when he could afford it. In 1955, when he finished the year on tour, he began taking flying lessons, and soloed in 1956, getting his private pilot’s license that same year. In his early flying days, he trained in Cessna 172s, 175s and 180s, and began chartering aircraft.

Palmer bought his first plane, an Aero Commander 500, in 1961. In 1963, he traded up to a Commander 560F. He acquired his first jet, a Rockwell Jet Commander, three years later. After that, he flew a Lear 24 for nine years. Later, he started a long-term relationship with Cessna aircraft, through his attorney, Russ Meyer, then chairman of Cessna. He’s worked his way from a Citation I to a Citation X.

Some pilots who have gone from flying turboprops to flying jets like the Citation X have lamented the fact that their days of “pleasure flying” are gone. Palmer takes a different attitude.

“My pleasure ‘is’ flying my jet,” he says.

Read More: Arnold Palmer and his Chief Pilots—A Close-knit “Fraternity” – By Di Freeze

Stuck Between A Medal & A Court-Martial – Bob Pardo

The day was March 10, 1967, and Capt. Bob Pardo was flying an F-4 Phantom out of Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand. He had been sent on a mission to strike the only steel mill in North Vietnam, in Thai Nguyen.

The day was March 10, 1967, and Capt. Bob Pardo was flying an F-4 Phantom out of Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand. He had been sent on a mission to strike the only steel mill in North Vietnam, in Thai Nguyen.

Flying tail end Charlie with a strike force escorting F-105s, Pardo was within about 50 miles of the target when Earl Aman and his backseater, 1st Lt. Robert Houghton, took a hit, and then, arriving at the target, took another from antiaircraft fire. Soon, Pardo and his backseater, 1st Lt. Steve Wayne, would also be hit.

As they left the target, Pardo lagged behind, mindful of Aman’s seemingly more critical problems. With both dangerously low on fuel, Pardo had continued to fly formation with Aman, until eventually, after trying other methods, he was able to push Aman’s ailing craft to relative safety.

“Pardo’s Push” was accomplished by having Aman lower the large tailhook beneath Aman’s aircraft, to rest as gently as possible against Pardo’s windshield. Later, when the windshield began showing cracks and gouges, the tailhook was placed against the metal just below the windshield. At times, Pardo operated without his left engine, which had caught fire and needed to be shut down. He would fly the last 10 minutes on one engine. Once over the Laotian jungle, it was time to get out from underneath Aman’s aircraft. Pardo and Wayne watched both Aman and Houghton punch out, and seeing chutes open, headed for a LIMA sight with a pierced steel planking runway, estimated to be 25 or 30 miles away, which would provide a good place to belly in and crash land “among friendlies.”

However, less than halfway there, they flamed out and both pilots punched out, coming down about 20 miles north of Communist-held Ban Ban. It was “not a very good place,” but at least, as Pardo put it, it was “better than going down in North Vietnam.”

Breaking branches and limbs as he went along, eventually his canopy collapsed and Pardo found himself freefalling, then landing in rocks, where he stayed slightly conscious for a couple of minutes, before slipping into unconsciousness.

To find out what happened next, read “Stuck Between a Medal and a Court Martial” – By Di Freeze

Careful First, Freedom Second – Sydney Pollack

When Sydney Pollack, Academy Award-winning director, producer and actor, thinks about flying, a couple of words come to mind.

When Sydney Pollack, Academy Award-winning director, producer and actor, thinks about flying, a couple of words come to mind.

“I would say the first word is ‘careful,’ followed then by the word ‘freedom,'” says Pollack, adding that with the kind of flying he does, it’s important not to get those words out of order.

That kind of flying is from the left seat of a Cessna Citation X, a mid-size aircraft that’s the fastest business jet available today. He’s been piloting the jet for three years, and bases it at Clay Lacy Aviation, at Van Nuys Airport in California.

Pollack said that as a child, he had a normal interest in aviation, but it wasn’t until after he got married and was in the Army Reserve that he really got interested. His wife’s father, a general in the Air Force, had a Boeing Stratocruiser assigned to him, and gave Pollack a ride in it. The next turn of events that led to his “obsession” with aviation was a ride he took with screenwriter and producer Roland Kibbee.

“It was in the middle of the afternoon, on a beautiful autumn day,” Pollack said. “We were working on the script, and he was sort of looking longingly out at the sky, obviously not wanting to be working, but to be flying. He just said, ‘Come on. Let’s go fly.’ I’d never been flying, really; not in that sense. That’s how it started.”

Pollack says that the most difficult thing about flight training is that he has “a day job.” He described the two-week Lear school he attended as grueling, but said the 21-day Citation X course was worse. Although flying is a lot of work these days, he says it’s definitely worth it, and he’s given a lot of thought as to why it is.

“It started out purely as pleasure; I just loved flying,” he said. “Then it graduated to the sense of freedom of it, a kind of sensuality, to a sense of pride in being able to do it well as it got more difficult.”

To hear more about what aviation means to Sydney Pollack, read “Careful First, Freedom Second” – By Di Freeze

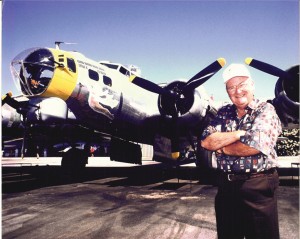

An Enthusiastic Collector – Bob Pond

Bob Pond is proof that when you do what you love, the rest will work itself out. Perhaps no other place proves the validity of this multimillionaire’s daring philosophy like the Palm Springs Air Museum in California. There, enthusiasts from all generations still gather to enjoy his extraordinary collection of fighting airplanes and dashing automobiles.

Bob Pond is proof that when you do what you love, the rest will work itself out. Perhaps no other place proves the validity of this multimillionaire’s daring philosophy like the Palm Springs Air Museum in California. There, enthusiasts from all generations still gather to enjoy his extraordinary collection of fighting airplanes and dashing automobiles.

From his first bumpy ride at Chicago’s Meig Field in 1935, to flying PBY4 bombers for the Navy Air Corps during World War II, Pond has loved piloting a diverse range of aircraft. In more than 60 years of flying, he’s amassed 22,000 hours.

The celebrated businessman made his fortune by growing his grandfather’s Advance Machine Company into the world’s leading manufacturer of industrial cleaning equipment. When his business career started to take off, he was the first to recognize the utilitarian nature of airplanes.

Then, once he had his feet under him financially, in 1970, Pond took advantage of his success to start collecting aircraft, beginning with a P-40 Warhawk and a P-51 Mustang. His collection grew to include a whole range of Grumman “Cats,” a rugged B-17 Flying Fortress, a Spitfire and two Douglas A-26C Invaders. His B-25T Mitchell is one of the most flown aircraft, appearing in the film “Pearl Harbor,” and still highlighting air shows at the museum.

A lifelong fan of automobiles, Pond has also accumulated a collection of more than 100 classic cars. But it’s not just airplanes and other high-velocity vehicles that get Pond’s attention these days. He also gives a great deal of time, money and energy to ensuring that future generations are given the same opportunities that he enjoyed. He funds a number of significant projects and scholarships at his alma mater, the University of Minnesota, but his heart belongs to the Palm Springs Air Museum.

“It’s the center of my life now,” Pond said. “It’s one of the top attractions in Southern California and it’s great to enjoy the direction that it’s going. There’s no way to really get the sense of what a wonderful museum it is without visiting it in person.”

To find out how Bob Pond and a dedicated group of museum enthusiasts launched the Palm Springs Air Museum, read “Pond & Palm Springs Museum” By S. Clayton Moore

The Right Role – Dennis Quaid

It wasn’t a stretch for Dennis Quaid to play Capt. Frank Towns in “The Flight of the Phoenix.” Quaid has been a pilot since the early eighties. He decided to learn to fly to ready himself for the role of Mercury astronaut Capt. Gordon Cooper in “The Right Stuff,” released in 1983.

It wasn’t a stretch for Dennis Quaid to play Capt. Frank Towns in “The Flight of the Phoenix.” Quaid has been a pilot since the early eighties. He decided to learn to fly to ready himself for the role of Mercury astronaut Capt. Gordon Cooper in “The Right Stuff,” released in 1983.

“I felt like I should learn to fly, because that’s what these guys did,” he said. “It helps you get into the role. Right after getting it, I found out Gordo Cooper lived a couple of miles from me in LA. I went over and talked to him, and he turned me on to Clay Lacy.”

Before that, Quaid admits, he was afraid to fly.

“I really didn’t understand aerodynamics,” he said. “Also, I had an ex brother-in-law who took me up in a little plane, cut the engine and put it into a spin. So I was sort of turned off to little planes.”

He recalls his flight with the expert pilot that would help turn that fear to excitement.

“Clay gave me a ride in a Learjet at about 50 feet off the deck over the Mojave Desert,” he said. “That was quite a thrill.”

In 1981, Quaid soloed in a Cherokee 180.

“I think every pilot remembers that moment,” Quaid grins.

In his early days of flying, Quaid rented various aircraft, before acquiring a TC Bonanza.

“For the way I use airplanes, it’s maybe the best plane I ever had,” he said. “I kind of wished I hadn’t sold it.”

After the Bonanza, he got checked out for twin-engine aircraft, and bought a Cessna 421, before purchasing a Cessna Citation II.

“I went down to FlightSafety and got certified for jets,” he said. “The first year I got my Citation, I flew it about 400 hours. The last year I had it, I flew it less than 100 hours.”

He lists flying over the Grand Canyon as one of his more memorable flights.

“We flew over before they shut it down for flyovers,” he said. “We came over the Grand Canyon pretty low. That was really something. I loved that flight. It was just like being on a magic carpet.”

Read more: The Right Role for Dennis Quaid – By Di Freeze

In Love with the Sky, But Willing To Change It – Vern Raburn

Vern Raburn has been described as a tsunami—he can’t be controlled or stopped. From the beginning, naysayers tried convincing Raburn, founder and CEO of Eclipse Aviation Corp., he’d never get his very light jet off the ground. Raburn ignored skeptics and kept on going.

Vern Raburn has been described as a tsunami—he can’t be controlled or stopped. From the beginning, naysayers tried convincing Raburn, founder and CEO of Eclipse Aviation Corp., he’d never get his very light jet off the ground. Raburn ignored skeptics and kept on going.

When we first interviewed Raburn, he had just made it beyond one hurdle—changing the power plant on his Eclipse 500 jet from a Williams to a Pratt & Whitney. That set FAA certification back.

“If anyone believes that we’re not going to have our Eclipse certified, they better sit down,” Raburn said at the time.

Recently, everyone stood up—in applause—when FAA Administrator Marion Blakey, in a special ceremony at EAA’s 2006 AirVenture, presented Raburn with provisional FAA type certification for the Eclipse 500. Full certification is expected soon.

Raburn, Airport Journals’ 2005 Aviation Entrepreneur of the Year, believes that the revolutionary Eclipse 500, a six-place, twin-engine jet, will forever change how people travel point-to-point. He also believes that Eclipse Aviation sets an example of taking risks; it has changed the way others within the aviation industry are doing business.

“There’s been no competition in general aviation for a long, long, long time,” says Raburn, who received the 2005 Collier Trophy.

He’s speaking in past tense, because there’s competition now.

“It always takes some asshole like me to come in and shake things up,” he quips. “It’s always when people and companies come along and say, ‘No, we can do a better job,’ that competition truly sets in.”

Raburn said the Eclipse 500 was “designed to serve both the existing general aviation market and a new market,” which the company termed the “air limousine” concept. An accomplished pilot, and former executive in the IT sector for several large companies, he began working on his aircraft business concept in late 1997.

In March 2000, the launching of Eclipse Aviation Corporation was formally announced. The company revealed that the Eclipse 500 aircraft development program was “designed to apply technological breakthroughs in creating a series of safe, reliable, low-cost, jet aircraft” that would enable transformation of the U. S. air transportation system. A group of high-technology auto and aerospace executives backed Eclipse with the initial funding of $60 million.

To read more about Vern Raburn and the making of the Eclipse 500, read In Love with the Sky, But Willing and Able to Change It – By Di Freeze, Eclipse Founder and CEO Vern Raburn Won’t be Stopped <http://www.airportjournals.com/Display.cfm?varID=0403003> – By Karen Di Piazza and NAA Says “Don’t Bet Against Eclipse”—Winner of Collier Trophy <http://www.airportjournals.com/Display.cfm?varID=0607004> – By Karen Di Piazza.

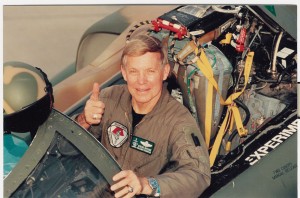

The Last Ace – Steve Ritchie

Brig. Gen. Steve Ritchie, the only U.S. Air Force pilot ace of the Vietnam Conflict, says he’s been fortunate to have had “incredible life experiences.” Those experiences have led him to travel millions of miles, visiting all 50 states and many foreign countries, as a motivational speaker and to support Air Force recruiting efforts. He’s given more than 5,000 speeches for young people, civic clubs, high schools, colleges and nonprofit organizations.

Brig. Gen. Steve Ritchie, the only U.S. Air Force pilot ace of the Vietnam Conflict, says he’s been fortunate to have had “incredible life experiences.” Those experiences have led him to travel millions of miles, visiting all 50 states and many foreign countries, as a motivational speaker and to support Air Force recruiting efforts. He’s given more than 5,000 speeches for young people, civic clubs, high schools, colleges and nonprofit organizations.

“I strive to encourage youngsters and try to be an inspiration the way people like Robin Olds and Carl Miller were to me,” he said. “I’ve quoted General Patton so many times: ‘We fight with machinery, but we win with people.'”

According to Stephen Coonts’ book, “War in the Air: True Accounts of the 20th Century’s Most Dramatic Air Battles by the Men Who Fought Them,” Ritchie is the “last of the breed.” He’ll most likely be the last fighter pilot to become an ace, due to the changing nature of warfare. The last chapter of Coonts’ book, “The Last Ace,” tells Ritchie’s story.

When a friend on his high school football team encouraged him to attend the Air Force Academy, Ritchie considered it, even though he “really wasn’t all that interested in flying.”

“Going out west to Colorado and being a part of this big new school sounded exciting though,” Ritchie said.

He graduated from the Air Force Academy in 1964, and began his first combat tour in 1968. After flying 195 missions with the 366th Tactical Fighter Wing, Ritchie returned to the USAF Fighter Weapons School at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, where he would be one of the youngest instructors in the school’s history.

On May 10, 1972, Ritchie, assigned to the 555th (“Triple Nickel”) Tactical Fighter Squadron and flying an F-4 Phantom, scored his first aerial victory. On May 31, he scored his second victory, and on July 8, he downed two more MiG-21s. He scored his fifth victory on Aug. 28, while flying his 339th combat mission. Ritchie had become the second pilot ace of the war, the only Air Force pilot ace of the war, and the only American pilot to down five MiG-21s.

The day after his last victory, Ritchie, with 800 hours of accumulated combat time, received orders not to fly anymore. Sentiments were that if the only MiG-21 ace were to be shot down, it would be a “great propaganda victory.”

To find out what Steve Ritchie’s up to now, read “The Last Ace” – By Di Freeze

Time Must Have A Stop – Cliff Robertson

Cliff Robertson, Academy Award and Emmy Award winning screen star, recalls reading “Time Must Have a Stop,” by Aldous Huxley, years ago, and wondering about the title.

Cliff Robertson, Academy Award and Emmy Award winning screen star, recalls reading “Time Must Have a Stop,” by Aldous Huxley, years ago, and wondering about the title.

“I never knew what he meant, but I’m beginning to realize now,” he said. “We need more time!”

The 2006 National Aviation Hall of Fame inductee would like more time to devote to his immediate family, as well as to his closest friends, and to flying his airplanes. That includes his Grob Twin Astir, a two-place glider he keeps at High Country Soaring in Minden, Nev., on the eastern side of the High Sierras, which he says is the best place to soar in the world.

He shares that passion with friends like Barron Hilton, whose Flying M Ranch is about 35 miles from High Country. Robertson has his diamond altitude, for over 26,000 feet. A few years back, he and a friend set a Nevada state record for distance in a two-place glider—240 miles, from Tonopah to Parowan.

But gliding is only a part of his aviation “obsession.”

“I have a big hole in my head and a stable of planes,” says the man who holds single-engine land and sea, multi-engine, instrument and commercial licenses, as well as balloon, gliding and seaplane ratings.

Those planes include a Beech Baron 58; a Messerschmitt Me-108, which is on display in the Parker-O’Malley Air Museum in Ghent, in upstate New York; and a Stampe SV4, a French fully aerobatic open-cockpit biplane. In the past, he’s also owned three Tiger Moths, as well as a Spitfire Mk.IX.

Robertson was a 5-year-old living in La Jolla, Calif., when he became aware of aviation.

“I saw a little yellow airplane doing aerobatics over our house,” he said. “My uncle and another man were standing there watching the aerobatics, wagging their heads sagely, and one said, ‘You’ll never get me up in one of those little airplanes.’ Then the little airplane turned southward and started to hum its way home. We got into the Ford alongside the curb and it wouldn’t start. In my little mind, I was thinking, ‘What’s wrong with this picture?’ I think I began to become a partisan for aviation at an early age. I was defending it then, and I still am.”

To read more about Cliff Robertson’s passion for flight, read “Time Must Have a Stop” – By Di Freeze

From Curtiss To Cobra – Carroll Shelby

Most people don’t equate the name of Carroll Shelby with aviation. But automotive industry legend Shelby is a pilot. He’s actively used his twin-engine Aerostar, based at Petersen Aviation at Van Nuys Airport, to commute back and forth to his manufacturing plant.

Most people don’t equate the name of Carroll Shelby with aviation. But automotive industry legend Shelby is a pilot. He’s actively used his twin-engine Aerostar, based at Petersen Aviation at Van Nuys Airport, to commute back and forth to his manufacturing plant.

He’s also used that aircraft to fly to his ranch in east Texas. Besides the Aerostar, he owns a Cessna and a fixed-wing ultralight.

“This plane is the only thing that I can fly because they don’t allow any pilots with an organ transplant to fly any registered aircraft,” said Shelby, who has had both heart and kidney transplants.

He enjoys attending EAA AirVenture Oshkosh, often flying with Chuck Yeager, Barron Hilton and actor Cliff Robertson. When time permits, he enjoys hanging out with longtime racing friend and aviation aficionado Robert E. Petersen, founder of Petersen Aviation and Hot Rod magazine.

During World War II, one of his fondest flying memories was dropping letters placed in his flying boots over his fiancée’s farm, while on training missions. He served out WWII as a flight instructor and test pilot of the Beechcraft AT-11 Kansan and Curtiss AT-9 Jeep.

In 1956, Sports Illustrated named Shelby Sports Car Driver of the Year. He received the title of Driver of the Year in 1957. His accomplishments as a race car driver include breaking land speed records at Bonneville in 1954 for Austin Healey and winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1959 alongside teammate Roy Salvadori. He was inducted into both the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in 1991 and the Automotive Hall of Fame in 1992.

Suffering health problems, Shelby stopped racing in 1960, but focused his talents in other areas. As a team manager, he was a part of the FIA World Grand Touring Championship as well as Ford GT victories at Le Mans. Carroll Shelby became a household name in the sixties, with his 427 Cobra models and Shelby Mustangs he built for Ford.

Located in Las Vegas, Shelby American, Inc. has produced at least 40 editions of the Shelby Cobra.

To read more about Carroll Shelby, read Carroll Shelby—from Curtiss to Cobra – By Di Freeze