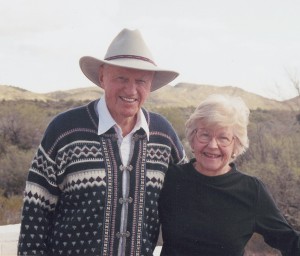

Harry and Virginia Combs at their home in Wickenburg, Ariz.

Harry and Virginia Combs at their home in Wickenburg, Ariz.

It was 1917. Four-and-a-half year old Harry B. Combs, who would one day make his mark on aviation history, was traveling across the country on a three-day trip from Denver, Colo., to his final destination—a Royal Flying Corps training field in Deseranto, outside of Toronto, Canada. Nearby sat his grandmother, who was taking him to visit his father, a pilot in training for the Corps. Once in Buffalo, they took a boat across Lake Ontario.

“I remember my grandmother telling me, ‘Now, this is not the ocean. This is one of the Great Lakes,'” Combs said, from his winter home in Wickenburg, Ariz.

For Combs, who was born on Jan. 27, 1913, the son of Albert Henry and Mildred (Berger) Combs, this would be his first glimpse of “an aeroplane.”

Once in Deseranto, Combs’ father illustrated what he and other pilots had learned.

“He folded a piece of paper in the form of a dart and threw it,” said Combs. “‘Now,’ he said, ‘we turn the back end of it up (resulting in) elevators, and do a loop to loop.’ He turned the ends down and it dove into the ground. He turned one end up and one end down and it spiraled.”

Wide-eyed, the child followed his father out to the airfield—a cow pasture.

“There were all of these planes lined up and they were beautiful,” said Combs, launching into a description of the material that was used back then to make the cloth wings on aircraft. “Today we use Flytex. Those days there wasn’t any Flytex, which is better but isn’t as nifty, so they used Irish Linen—166 strands per inch. You could put your hand under the wing and see it. The wings were so shiny—almost transparent.”

Now 88, Combs clearly remembers his excitement of watching an airplane roll out.

“Some guys were turning the prop,” he says. “Others were holding the wings. He explains that then, aircraft had no brakes, only a tailskid. “The fellow who was going to fly put on a pair of goggles and helmet and got in the cockpit. The mechanic yelled, ‘contact,’ and whirled the propeller around and that engine just started roaring. I jumped up and down and thought, ‘Oh boy!'” He also remembers how, one afternoon, a thunderstorm sprung up, causing tremendous wind, and causing the crash of about 16 aircraft in 12 minutes. He remembers the distress of his grandmother, but his innocent reaction—he wanted to see the excitement again!

In 1920, Combs, now seven, set off on another adventure. He headed off to Massachusetts for Fessenden, a preparatory school for boarding school, built on “the old British system.” He would be there for six years before attending Taft School, a boy’s preparatory school (later a coeducational boarding school) in Connecticut, where he would spend five years.

“He had to eat lamb chops going all the way across the country,” says Virginia (Ginney) Combs, the aviator’s wife of 45 years. (The couple met scant weeks after meeting.) “That was the only thing he could read on the menu. They sent him off on the train with a tag on that said, ‘put this child off in Chicago.'”

While in school, he remembers reading a book, “Warbirds: The Diary of an Unknown Aviator,” by Elliott White Springs, later considered my many as the most important writing on World War I aviation ever produced. White Springs’ words, “I’m absolutely spoiled for anything else,” referring to flight, had Combs itching to try it.

In 1926, on summer vacation back in Denver, Combs and a friend named Rocky Hall, both “bicycle kids,” decided that they “just had to fly.” This, in spite of the fact that Combs’ father, who had been shot down twice during the war, told him never to get in an airplane.

They hopped on their bikes and pedaled to an airfield at 26th and Oneida.

During the last several years, general aviation in Colorado had taken big steps. Three Denver airfields established in the 1920s, within blocks of each other, played a significant role in the early years of Colorado aviation history.

These airfields were located at 26th Avenue and Oneida Street, 38th and Dahlia Street, and 46th Avenue and Colorado Boulevard. Each airport ran under several names over the years.

The airport at 26th and Oneida came into being when Ira Boyd “Bumps” Humphries and his younger brother, Albert E., soloed in OX-powered Jennies in 1918.

After WWI, both brothers returned to Denver. Bumps formed the Curtiss-Humphries Airplane Company in 1919 to open and maintain an airport, sell airplanes, and engage in other air operations, including, in its early years, passenger service/sightseeing trips (at the rate of $12.50) to limited areas.

By the following year, the company had eight aircraft—five Curtiss Orioles and three Curtiss Standard J-1s. The field was also the site for the Martin-Sweet Motor Company, which operated until 1921.

In 1921, Humphries surrendered his Curtiss distributorship and sold his aircraft to devote his time to oil and mining interests. The next owner was Don Hogan, a successful automobile dealer. When Colorado Airways won the contract to carry airmail over a route that included Cheyenne, Denver, Colorado Springs and Pueblo in 1926, they leased the field from Hogan. (In 1934, Walter Higley bought the airport and formed Colorado’s first flying school; it became known as Higley Field. Then, in 1942, the Colorado Wing of the Civil Air Patrol assumed control of the field. They remained there until 1947.)

In January 1924, Lowry Field at Denver’s 38th Avenue and Dahlia Street was opened to await arrival of the 120th Observation Squadron, Colorado Air National Guard (activated in late 1923) aircraft. The 120th started flight operations, on grass runways, with eight JN-4 Jennies, WWI surplus aircraft, which were housed in two corrugated steel hangars.

When the Post Master General canceled Colorado Airways contract, Boeing Air Transport ran an airmail operation from this field, as did one other airmail operator— the US Army.

The third airfield was located at 46th and Colorado Blvd. In the mid-1920s, this field, Denver Union Airport, totaling 391 acres, was the location for the Colorado School of Aeronautics, Rocky Mountain Airlines, and the Rocky Mountain Flying Club, all owned by Frank Van Dersarl.

Curtiss-Wright took over the operation in 1930. Frank stayed on until 1933. In the following years, the airport went through several names.

The field set up by “Bumps” and “Al” was the field that Combs and Hall rode to.

“Bumps and Al had a lot of dough and lived in a mansion between 7th and 8th streets on Pearl, across from the big red brick house where I lived,” said Combs. When they decided to take up flying, the boys searched for the “best” plane, and in 1919, purchased an Italian-made biplane, the Ansaldo.

Combs and Hall arrived at the field with $4 between the two of them. After a mechanic heard of their plight, he arranged for a pilot to take them up for the meager amount. The money exchanged hands, and soon they had squeezed into the front seat of the Ansaldo, once owned by the brothers.

“We were real jammed,” says Combs. “It was only meant for one man.” Soon, they heard the familiar, “Contact!” They were off. “We taxied out and then he poured the coal to it. It was roaring like hell. Suddenly, we were airborne.” Later, the boys experienced their first wingover. Hall didn’t know quite what to think. The ride was now almost over. The boys saw the ground getting closer and closer, then, bump, bump, bump, they had touched down. Combs was hooked.

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh made his historic flight across the Atlantic. The next year, Combs, still attending Taft, was rooming with Henry Dingley.

“We had hung up a blanket in our room,” says Combs. “We took pictures out of aviation magazines of nifty races, like the King’s Cup Races, and hung them up.” In the process of looking for pictures, the boys came across an ad in a magazine: “Learn to fly for $99.”

“It was Charles Lindbergh’s old company,” said Combs. The allure was too great. But how to get St. Louis? Luckily, Dingley, 17, was in possession of an automobile. In June 1928, they set off for Robertson Aircraft Company at Lambert Field. They were going to learn to fly!

“I lied,” says Combs. “I did! I told them I was 17, but I was 15.” He smiles. “But the statutes of limitation have run out now, and I don’t give a damn!”

The boys stayed in a small house near the airfield for two weeks. It would be days before they had their chance to train in an OX5-powered Curtiss Standard J-1, a biplane.

Finally, it was time for his first lesson with his teacher, Julius Johan Peter. The first few minutes were tough.

“The planes weren’t like planes today,” says Combs. “You were constantly correcting them to make them fly right. All of a sudden, I got the idea. Then we did everything. After three hours and 45 minutes, (my instructor) said, “You’re ready.” Combs admits that he wasn’t ready to solo, because he hadn’t tried any spins or other aerobatic maneuvers, but that was what $99 paid for.

Later, Combs bought flying time in the long-winged Alexander Eaglerock, nicknamed “the Brick.” After the aviator had about 30 hours of flying time under his belt, he decided to try his hand at building his own sport biplane, and, at the age of 17, completed the Vamp Bat—which he had been working on for two years—with the help of Frank Van Dersarl. The Vamp Bat’s short life ended when, after flying it to Pueblo, Combs lost control of the airplane on a runway, while taxiing into position in a high wind.

“You didn’t have any means of controlling when the wind was blowing,” says Combs. “There were no brakes—just a tailskid. If you sped up, it got away from you and you turned upside down. I was hanging upside down inches from the ground. It busted up. I should have known that when you don’t have brakes you have to (stay) on the grass.”

In 1931, Combs entered the hallowed halls of Yale University, in New Haven, Conn., where he enrolled in Sheffield Scientific School, majored in applied economics, and participated in and lettered on both the school’s track and football teams. He also served as president of St. Anthony Hall, Delta Si Fraternity and Torch Honor Society and chairman of Cannon & Castle Military Society.

Upon graduation in 1935, Combs attended the Colorado School of Mines for a summer camp (reserve officer’s training), where he was commissioned ROTC second lieutenant, U.S. Army Corp of Engineers.

He laughingly tells how he had no interest in becoming an engineer, and as a “smart” businessman, offered to pay an engineer to do a stress analysis test on a bridge for him; after all, wasn’t that what smart businessmen did?

Cadet training would have followed, but Combs was in love, and cadets couldn’t marry. (He married Clara Van Schaack in 1936. The marriage, which lasted until their divorce in 1954, produced three children, Harry B. Combs Jr., Anthony Combs, and Clara Combs Moore.)

After graduating in 1935, and taking a trip to Europe, he took a job as a ticket agent with Pan American Airways. 1937 brought more changes. He began working for an investment banking company, Bosworth, Chanute, Loughridge & Co., in Denver and, in the meantime, was commissioned as a second lieutenant pilot officer in the 120th Observation Squadron, Colorado National Guard, where he would get the chance to rack up hundreds of hours of flight time in the Guard’s biplanes.

“I flew and flew and flew, with Uncle Sam paying the bill,” Combs said. “I started getting 30 hours a month.” Soon, he had his commercial license and his flight instructor rating, which also resulted in flight hours paid by someone else—the student.

Along with the investment banking business, Combs, after earning his instructor rating, hired on as an instructor with Ray Wilson, the future founder of Monarch and Frontier Airlines, who was operating a flying school. Wilson’s flying school, Ray Wilson Flight School, was located at 46th and Colorado Boulevard.

When a fellow employee warned Combs, who had been out instructing each morning for an hour or two before arriving at the office to sell barns, that “management is not going to hold still for you exercising your energies elsewhere,” he decided that it might be time to exercise all of his energies elsewhere.

In 1938, the Colorado Air National Guard abandoned Lowry Field and moved to Denver Municipal Airport (later Stapleton Airport), which had opened in 1929, taking their hangars with them. This gave Combs the opportunity to lease the field, about 30 acres, from Charlie Boettcher.

On this site, in the winter of 1938, Combs incorporated Mountain States Aviation, a flying school and aircraft sales division.

The school started with one “air knocker”—a 50-hp Aeronca. Combs traveled to Middletown, Ohio, to the Aeronca factory, to pick it up. Arriving, he called a roommate from college, Ted Gardner, who lived in nearby Dayton. As any ex-roommate should, Gardner invited Combs to spend the night. When Gardner’s mother heard what business he was going into, she offered to introduce Combs to a good friend by the name of Orville Wright, who happened to live down the street.

True to her word, Mrs. Gardner placed the call. Mr. Wright was not available the following day, but he was available the next day. But there was a time conflict; Combs had been invited to dine with an FAA agent and Jimmy Doolittle in St. Louis. Although at the time, meeting with Doolittle, a “god,” was more important, in later years, Combs would dearly regret the missed opportunity.

“At the time, I only knew that Orville was the first to fly,” says Combs. “It wasn’t until I write “Kill Devil Hill” (1979) through the instigation of my friend Neil Armstrong, that I discovered the enormous contribution made by both brothers.”

Soon, Combs and his new airplane were back in Denver—well, actually, not soon enough. The trip home was “rough and slow.” The trip from Goodland, Kansas, to Denver alone, flying against a strong wind, took nearly three hours.

Although with a slow plane, Combs was soon instructing. He instructed his first student (through his new company) on Jan. 29, 1939.

Soon, the first plane was replaced by a 55-hp aircraft, which was eventually replaced by one with a 65-hp Continental, etc. Eager students purchased many of the discarded aircraft.

And soon, Combs had a partner. Lou Hayden, who had purchased an aircraft from Combs, came on board two months after the business started, and began instructing.

In 1939, Combs established Combs Aircraft Corp., to design and build an experimental aircraft known as the Combscraft, an economical, low-wing, retractable gear monoplane. Years later they would find out that the reason the aircraft couldn’t pass a spin test (the nose of the aircraft had a tendency, while rotating, to come up) was because the fin on the craft should have been twice its original size. But, due to the company’s war efforts in upcoming years, the project would be abandoned.

As with all aircraft sales companies, Combs searched for a franchise. The Piper franchise wasn’t available; Wilson had it. Someone in Cheyenne had already gotten his hands on the Aeronca franchise.

But there was one sure-fire way of making money, other than a franchise. There was the government’s Civil Pilot Training Program.

“They told us that if we got so many instructors, we could get a contract and train 10 guys and they’d pay us so much per hour,” says Combs, “but we had to be certified.” And so began a long, hard process. The morning came when the “fellow from the Navy” arrived at the field. Combs grabbed an old Taft sweater and threw it on. The first thing that happened was he was asked if he was trying to “impress someone?”

“No, I’m trying to keep warm,” said Combs. Under the watchful eyes of the Civil Aviation Authority (later Federal Aviation Administration) inspector, Combs flew “the best flight he’d ever flown in his life,” to no avail. He was told that he had flown wonderfully, but that he had some things to work on. It looked suspiciously like the inspector had been “bought” to flunk him. But who would gain from Combs being unable to earn the lucrative government contracts?

But, according to Combs “the wheels of justice grind slow but they grind exceeding fine.”

About four months later, a new CAA administrator by the name of Stone, who had been a commanding officer of the 120th Observation Squadron and had been “framed out of his job to accommodate (Major Fred W.) Bonfils,” came to call. (Early in 1941, Maj. Bonfils and Ray Wilson, both in the 120th Observation Squadron, had formed the Wilson and Bonfils Flying School. They were awarded a contract for the civilian-operated primary flying school to give flight training to Army Air Corps flying cadets at Chickasha, Okla., followed by others.)

Sympathetic to Combs’ plight, and in agreement that he had been “plotted against,” he had a heart-to-heart talk with Combs. He told him that the Army Air Force was trying to decide on which of two planes, a two-place Stearman with a 165-hp Challenger radial engine, or a Waco, would be used for mid-point training. According to Stone, the decision was all but made up. Of course, it would be the Stearman. But the Waco, no doubt, would be used for civilian training, and anyone who landed a civilian flying contract (a secondary contract) would be lucky, indeed. These aerobatic contracts could earn $45 an hour, instead of the $12 to $15 primary contracts.

Stone’s plan unfolded. There were three Wacos in the hands of the military. If Combs would agree to go to Kansas City and take instruction from Joe Jacobson, one of the great aerobatic flying pilots of the day, and if he would agree to put down a deposit on a Waco, the government could loan him one of their existing Wacos, which they would soon discard, until he received his new plane. Of course, he’d have to pass the course. It sounded like a piece of cake—after all, Combs could do spins, loops, stalls. Easy.

Arriving in Kansas City, Combs, who now had between 1,500 and 1,800 hours, found that Jacobson had a Ryan ST—low-wing, all metal, fixed gear—a “wonderful stunt airplane.”

On went the helmet and the goggles. They stayed away from the paved runway, of course, because the plane had no brakes, but he was used to that. He already knew that when he wished to come down, all he had to do was land on the dirt, hold the stick back in his lap, and dig in with the engine back in idle. The first thing the instructor did was tell him that they would do a two and a half snap roll with a split S…a what??

“What’s that all about?” thought Combs. He’d never even heard of one. Soon, they were upside down and his feet came off the rudder pedals. He had noticed a dirty rag earlier along the throttle shaft and now knew what it was for — to wipe the oil off that now covered his goggles. Then, in midair, the engine quit. He was starting to get queasy and to believe that he couldn’t go on with his plan.

“I was thinking, ‘I’m too old. I have two kids. This is for racecar guys,’ said Combs. “I was sick. I Almost threw up. We landed, and it was hotter than hell. I lay down in the shadow of the wing on the grass, and thought, ‘I’m just not qualified to do this.’ Then I went and got a Coke, and lay down under the wing again. My stomach began to settle itself. I lay there and had a conference with myself. ‘Here you are Combs. You’re up against this, and you say you’re a married man with a family and you can’t do this. Joe’s just too tough for you.’ Then, I got to feeling better, and I had another Coke. ‘If we do this, if we get this thing, I could make a lot of money. Meanwhile, we’re starving.’ I finally convinced myself, ‘You’re just a yellow, son-of-a-bitch, that’s all you are! You haven’t got the guts to do what you’re up against and this is what you’re up against and you’d better do it!’ And so the conference ended. Combs stood up and walked over to Jacobson, and asked if he could take the plane up. After going over the maneuvers again, he took off, and it started again. He was upside down. The motor quit. He got the engine running again. He tried everything once, then four and five times.

“I near got around on one of them!” He says. Then, I got it! I did it again! I got my speed up and around it went. I came up smelling like a rose! I did it to the right, then to the left. I said to myself, ‘I don’t have to quit! Let’s do it some more!'”

Jacobson was in for a surprise. At Combs’ request, he went up with him that afternoon, and after an hour and a half, announced that Combs had learned much of what was covered in a two-week course! He then showed Combs how to “get the speed up by putting the nose down” while at altitude. He did just that. If he raised the nose to do a roll, he wouldn’t lose altitude.

“If you’re flying absolutely level, when you turn the airplane upside down, all the wind is pushing you up,” he says. “The lift is pushing downward, not upward. You can lose 200 or 300 feet and not come out even. You need extra speed. If you kept your nose on the horizon, you wouldn’t lose any altitude.”

But the next morning there were more problems. This time when the engine quit, at 10,000 feet, it didn’t start again. But Combs was bound and determined to make it back to the field. It was a coin toss as to whether the “air traffic controller” would flash a red light from a flashlight that said he couldn’t land, or a green one that said he could. It didn’t matter. Combs was landing anyway, and what the heck, he wasn’t landing on a runway. He came whistling in—on a green light, rolling right up in line with the other airplanes. Jacobson couldn’t believe his eyes, but there was the plane, and the pilot, uninjured. Combs was on his way. His training took two days instead of two weeks.

Back in Denver, the company soon had a new Waco, which they flew throughout the summer and fall, pulling in $65,000 in contract work. They soon had more good news. They were to be awarded Wilson’s primary Civil Pilot Training contracts, which included Colorado University in Boulder and Denver University.

They bought the land they were on and bought Wilson’s fields. They now owned three airfields. Wilson’s former airfield, soon be known as Hayden Field, was used to train students from D.U. Combs’ Field was used for their commercial business. The other field would be referred to as Boulder Field.

Soon, their aircraft included eight Wacos and 30 Cubs. Between 1940 and 1944, Mountains States Aviation trained 9,000 pilots, with 45 planes, 45 flight instructors and 160 employees.

In 1944, Combs joined the U.S. Army Air Force Transport Command, flying four-engine C-54 transports on North Atlantic, Africa and India routes. He did this for a year, when, after applying for the separation board, he was given an honorable discharge, and returned to his company, which was in financial trouble. There were too many military contracts! Too many aircraft orders to fill! They had earlier snagged a contract with Piper (as a dealership) but it had been canceled. After hiring extra help and filling orders, they were reinstated.

“We were sweating all of the time trying to make people happy,” says Combs. He quickly began building it into one of the most successful FBO chains in the U.S.

In 1944, Denver Municipal Airport was renamed Stapleton Airport. (It would not become Stapleton International Airport until 1964.) By the late 1940s, air congestion near Stapleton Airport had become a serious problem. A campaign began to shut down Combs Air Field. The reasoning was that the small planes landing and taking off at Combs were a danger to both residents and planes going in and out of Stapleton. Two major crashes had occurred there, due to recent land development in the area.

In the meantime, in 1945, Combs was appointed to the newly formed Colorado Aeronautics Commission.

In 1948 Mountain States Aviation’s Piper, Stinson, and Ryan Navion aircraft operations moved to Hangar 2 at Stapleton Airport. The last flight, a Ryan-Navion aircraft, left Combs Air Park in 1949.

In 1950, Mountain States Aviation, which would eventually be credited for pioneering exceptional marketing and customer service techniques, obtained the coveted Beechcraft franchise for Colorado, Wyoming and Montana.

In 1954, Combs bought out Hayden’s share of the business; the fixed base operation and all of its operations were now known as Combs Aircraft Corporation. (In 1956, however, Mountain States Aviation was reactivated as a new corporation to handle Piper and Stinson dealerships.)

Hayden had entered into a separate business with (former) Governor Dan Thornton, which they were still running out of Hayden Field, which he now owned.)

Combs had been forced to sell their original property, due to a fault in the land title. It was worded that if the land were to later be used for anything other than aviation activity, the former owners would have the option to buy it back.

“We had bum legal advice,” said Combs, “and we were airplane people and didn’t know better. If we had kept it, we would have made millions.”

One of his new employees at Stapleton was Larry Ulrich, who is now the president of Denver jetCenter, a fixed base operation located at Centennial Airport, and a longtime friend of Combs.

“Harry’s a renaissance man; he’s a modern Leonardo da Vinci,” says Ulrich. “He’s a consummately good businessman because he’s always been able to see the big picture. There’s hardly anything he doesn’t know quite a bit about.”

Ulrich tells the story of how Combs, a Navion dealer, would often walk out on the wing to show a client just how strong the product was, even after he had come to believe that Beechcraft’s Bonanza was a better product. Ulrich also tells how, when he started with Combs, he started at the “bottom.”

“When guys tell me that they started at the bottom,” says Ulrich, “I tell them, ‘You haven’t seem bottom!'” Ulrich, the other half of the “gold dust twins,” a nickname given to him and Mike Berger, began, with toothbrush in hand, by cleaning old polish off of rivets of a B-35 Bonanza, working his way up to pumping gas on the line two years later. But he isn’t complaining — he considers himself lucky to have been one of Combs’ prodigies. He adds that this man, who he refers to as his second father, sounds remarkably like Jimmy Stewart — and he does.

“His 11th commandment is ‘thou shalt not bullshit thyself,” says Ulrich with a smile. Combs taught Ulrich valuable lessons like one learned from the tale of the rabbit and the fox. “He would tell me, ‘Son, in the eternal contest between the rabbit and the fox, why does the rabbit always win?’ then he would answer, ‘because the fox is running for his meal, but the rabbit is running for his life.’ Then he would say, ‘Run scared like the rabbit, and you’ll always survive.'”

Combs doesn’t deny that his employees worked hard and earned “just enough for grub.”

“The rest of (their pay) they took out in flying time,” he says. “We kept plenty of them out of the draft. They were taken in the Air Force, or went with the airlines. They ended up flying airplanes instead of charging around with a rifle. My dad was a fighter pilot in WWI. He used to say, ‘War is hell. You’d better ride into the war and not walk!'”

This is the first in a two-part series. Next month, learn more about the man who became Beechcraft’s number one distributor in the world, served as the president of Gates Learjet for 11 years, and became an award-winning author.

Harry Combs Enters The Jet Age – Part II