By Di Freeze

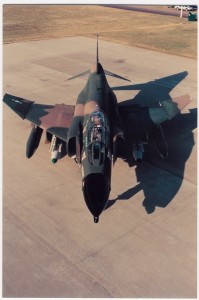

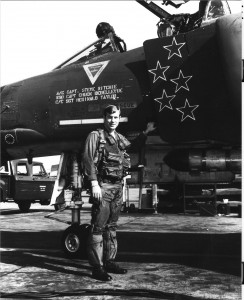

Brig. Gen. Steve Ritchie has flown the Phantom more than 100 times at air shows nationwide and special events. The actual aircraft in which he downed his first and fifth MiGs is on permanent display at the Air Force Academy.

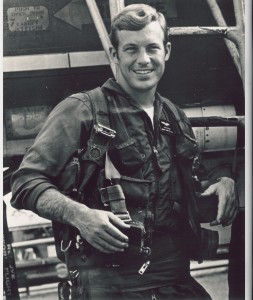

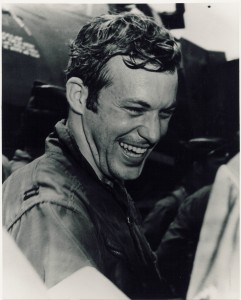

“Every day is a plus,” says Brig. Gen. Steve Ritchie, the only U.S. Air Force pilot ace of the Vietnam Conflict. “Every day I wake up thankful to be alive and healthy in the United States of America. Friends think I’m joking when I say I never thought I’d live this long, but it’s true.”

Ritchie, awarded the Air Force Cross, four Silver Stars, 10 Distinguished Flying Crosses, and 25 Air Medals, was inducted into the Colorado Aviation Hall of Fame in 1997. He served 10 years on active duty and 10 years in the Colorado Air National Guard, where he made the rank of lieutenant colonel. He served 15 years in the Air Force Reserve, completing his military service as mobilization assistant to the commander of Air Force Recruiting Service. He retired from the Reserve as a brigadier general in January 1999.

At about that time, he began flying a restored F-4 Phantom—the only privately-owned Phantom in the world—painted to resemble the one he flew most of the time in Vietnam. He has flown the Phantom more than 100 times at air shows nationwide and special events. The actual aircraft in which he downed his first and fifth MiGs is on permanent display at the Air Force Academy.

Ritchie, who recently moved from Monument, Colo., where his son Matt lives, to Florida, is president of AeroGroup Inc., a company that provides training and tactical air services for the military.

Ritchie says he’s been fortunate; he’s had “incredible life experiences.” Those experiences and his thankfulness for them have led him to travel millions of miles, visiting all 50 states and many foreign countries, as a motivational speaker and to support Air Force recruiting efforts.

He has given more than 5,000 speeches, many times pro bono, for young people, civic clubs, high schools, colleges, non-profits, etc.

“I strive to encourage youngsters and try to be an inspiration the way people like Robin Olds and Carl Miller were to me,” he said. “I’ve quoted General Patton so many times: ‘We fight with machinery but we win with people.'”

Among his personal heroes is former Air Force Chief of Staff Charlie Gabriel, who was Ritchie’s wing commander in Vietnam.

“He was a leader I would’ve died for,” Ritchie said. “That’s the way it is in our business. You’re with a group of people and your survival depends on your ability to protect each other—mutual support. Flying together in combat, as a unit, a team, forms very close relationships. It presents the ultimate challenge. When the bullets are real, it’s an entirely different scenario. There’s nothing else like it. It can’t be formed at IBM, General Electric, American Airlines or anywhere else. Those are great companies but it’s different in combat. Think about being in an arena where living or dying depends on winning or losing—and you win and you live. That’s exciting. It’s like winning the Super Bowl or the Master’s or Wimbledon. It’s the top of your game.”

Ritchie, although proud of his accomplishments, once again credits “the team.”

“I wouldn’t be a fighter ace or alive, if it weren’t for thousands and thousands of people that contribute to this entire network of people, airplanes, equipment,” he says. “Everybody that played a part in all that equipment and effort is ultimately responsible for what and who I am. What if the radio failed? What if the engine quit? What if the radar didn’t function? What if the missiles didn’t work or if the guns jammed? What if the intelligence information was incorrect? What if the electronic warning equipment gave false information? The list goes on and on. One can name 100 things that could have failed and I wouldn’t be alive.”

The Navy originally ordered the F-4B as a carrier-based fleet defense aircraft. The Air Force later ordered the F-4C. More than three-quarters of the USAF’s fighter wings were eventually equipped with the Phantom.

Ritchie seems to give a lot of thought to being “alive.” It’s no wonder, when you hear his story.

Born in Reidsville, N.C., a little town of about 15,000, on June 25, 1942, Ritchie says he was a “late bloomer” when it came to getting excited about aviation.

He was first introduced to the field, after his father, who was drafted into WWII and was in Patton’s Third Army in Europe, came back and used the GI Bill to get his pilot’s license.

“I flew with him one time in a little Piper Cub, but he didn’t have the money to keep flying,” Ritchie said.

When a buddy on the football team at his high school encouraged him to attend the U.S. Air Force Academy, Ritchie considered it, even though he “really was not all that interested in flying.”

“Going out west to Colorado and being a part of this big new school sounded exciting though,” Ritchie said.

He entered the Air Force Academy the same year that the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom, which first flew on May 27, 1958, entered active service.

The U.S. Navy originally ordered the F-4B as a carrier-based fleet defense aircraft. Soon after its introduction to active service in December 1960, a fly-off competition was conducted between the Phantom and various frontline Air Force fighters. The Phantom excelled in the competition and the U.S. Air Force ordered a slightly different version of the aircraft—the F-4C. (Over three-quarters of the USAF’s fighter wings were eventually equipped with the Phantom.)

As more and more pilots were flying the Phantom, Ritchie was often making his way across a football field, as starting halfback for the Falcons. He played during the 1961, 1962 and 1963 seasons, finishing his last season in the 1963 Gator Bowl.

During the summer before his senior year, he and others went through pilot indoctrination, each taking 12 rides in a Cessna T-37, a twin-engine primary trainer known as “Tweety Bird” or simply “Tweet.” This made up his mind.

“I got excited,” said Ritchie. “I said, ‘This is what I want to do.'”

After graduating in 1964, with a BS in engineering science, Ritchie headed to Laredo, Texas, for pilot training, where he was “lucky enough” to graduate first in his class.

His initial assignment was in Flight Test Operations at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, flying the Lockheed F-104 “Starfighter.” However, he would soon transition to the Phantom, which held the speed, altitude and time to climb records.

Richie began his first combat tour in 1968. Based at Da Nang Air Base, Vietnam, he flew with the 366th Tactical Fighter Wing (Gunfighters). He also flew the Air Force’s first official F-4 Fast-FAC (Forward Air Controller) mission in Southeast Asia.

“The F-100 Mistys were the first ones to fly FAC missions in a jet airplane,” explained Ritchie, “and then we flew it in a Phantom.”

After flying 195 missions, Ritchie returned to the USAF Fighter Weapons School (equivalent to the Navy’s Top Gun) at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, where he would be one of the youngest instructors in the school’s history.

In 1972, Ritchie volunteered for a second combat tour, and was assigned to the 555th “Triple Nickel” Fighter Squadron, based at Udorn Air Base, Thailand.

After the massive invasion by the North Vietnamese of South Vietnam on March 30, President Nixon suspended peace talks, and ordered Operation Linebacker, the renewed bombing of North Vietnam and the aerial mining of its harbors and rivers.

On May 8, Ritchie narrowly missed his chance to score a victory against an enemy MiG. He wouldn’t miss the chance, however, on May 10, 1972, an eventful day in many ways.

According to Stephen Coonts’ book, “War in the Air: True Accounts of the 20th Century’s Most Dramatic Air Battles by the Men Who Fought Them,” Brig. Gen. Steve Ritchie is the “last of the breed.”

That day, the Americans used laser-guided bombs for the first time against two of the most heavily defended targets in North Vietnam—the Paul Doumer Bridge in Hanoi and the railroad bridge at Thanh Hoa—and the North Vietnamese launched their largest aerial effort of the war against inbound American strikes. Also on that day, Navy Lieutenant Randy Cunningham scored three kills, making him the first American pilot ace of the war.

That day in May was also one of the low points in Ritchie’s career. When Ritchie learned that the number three pilot of Oyster Flight, a flight of four Phantoms scheduled to precede bombers to Hanoi, had failed to appear for a brief, he volunteered for the position.

Major Bob Lodge, a close friend of Ritchie’s and classmate from the Air Force Academy, would lead the flight. The other pilots would be 1st Lt. John Markle, flying Lodge’s wing, and 1st Lt. Tommy Feezel, flying Ritchie’s.

On several previous missions, North Vietnamese MiGs had orbited northwest of Hanoi, near the Yen Bai airfield, waiting to hear from ground control intercept. When vectored, they would ambush American strikes on their way to Hanoi to deliver their weapons.

Lodge and the others knew this because for several days, intelligence and mission planners of the 432nd Tactical Fighter/Reconnaissance Wing had been gathering data on the MiGs’ location and flight patterns.

As planned, the flight entered North Vietnam at a few hundred feet above the treetops. About 30 miles southwest of “bull’s eye,” Hanoi, the pilots picked up four MiGs orbiting northwest of Hanoi.

Soon, the Phantoms were climbing, and then heading straight at the MiGs. Lodge was the first to fire a Sparrow, and then another, and hit his mark. Markle did the same. The men watched as their targets exploded.

When the two remaining MiGs streaked in front of the Phantoms, from left to right, Oyster Flight closed in behind them. Ritchie, on Lodge’s left wing, would target the left MiG-21. Lodge would take the other.

With “their” MiG about 6,000 feet ahead, Ritchie’s weapons system operator, Chuck DeBellevue, succeeded in locking radar on the enemy aircraft. Ritchie followed every turn of the MiG, keeping it in the radar’s field of view for four long seconds while the seeker in the Sparrow’s nose phased in with the plane’s radar. He then squeezed the trigger, released it, and squeezed again. One after the other, the Sparrows ignited.

Ritchie watched, keeping the MiG within a 60-degree cone of his radar. He saw the MiG make a hard turn—and saw the first Sparrow miss. But the second detonated as it passed under the nose of the MiG.

Ritchie watched as the pilot ejected. He had scored his first victory. However, there wasn’t time to think about it; there was still one MiG left.

Lodge seemed to have the situation in control. He was in position, Markle to his right. Then, the unexpected happened.

“We saw a flight of MiG-19s coming in from behind readying for an attack on Oyster One,” Ritchie said. “We screamed over the radio for them to break off the attack.”

As Lodge and his backseater Roger Locher concentrated on the MiG-21, the incoming MiGs got into position quickly. Soon, 30-mm cannons peppered the Phantom. Ritchie watched in disbelief as the aircraft caught fire, rolled over and entered a flat spin within seconds. His eyes followed the plane as he searched, in vain, for parachutes.

Later, Ritchie, Feezel and Markle returned to Udorn. But there was no celebration for Ritchie’s victory, or the other two. No one knew the fate of Lodge and Locher.

It would be 22 days until they would know anything. On the twenty-third day, in one of the most daring rescues of the war, Locher, who landed about five miles from the Yen Bai airfield and managed to evade capture, was rescued.

He tells how Lodge told him to eject, but, it would seem, didn’t eject, himself. Lodge’s squadron members and friends remembered that during the morning briefing, more than three weeks before, Lodge expressed, as he had many times before, that should an emergency occur, he wouldn’t be ejecting. He had a Special Intelligence clearance, and didn’t want to risk giving away any critical intelligence, should he be captured and tortured.

The day after his last victory, Steve Ritchie received orders not to fly anymore. Sentiments were that if the only MiG-21 ace were to be shot down, it would be a “great propaganda victory.”

Ritchie’s second victory, another MiG-21, came on May 31, 1972, with Capt. Larry Pettit as his WSO. On July 8, with DeBellevue once again in the backseat, while leading a flight of four F-4 Phantoms, Ritchie doubled his score, downing two MiG-21s with three missiles in one minute and 29 seconds.

Flying the same aircraft in which he had scored his first kill, with DeBellevue again as backseater, Ritchie scored his fifth victory, on Aug. 28, 1972, while flying his 339th combat mission.

This was DeBellevue’s fourth victory as WSO. Before his tour would end, he would help another pilot score two victories, earning him six victories and the title of non-pilot ace.

As for Ritchie, he had become the second pilot ace of the war, the only Air Force pilot ace of the war, and the only American pilot to down five MiG-21s—North Vietnam’s most sophisticated fighter aircraft.

According to Stephen Coonts’ book, “War in the Air: True Accounts of the 20th Century’s Most Dramatic Air Battles by the Men Who Fought Them,” published in 1996, Ritchie is the “last of the breed,” and will most likely be the last fighter pilot to become an ace, due to the changing nature of warfare. The last chapter of Coonts’s book, “The Last Ace,” tells Ritchie’s story.

The day after his last victory, Ritchie, with 800 hours of accumulated combat time, received orders not to fly anymore. Sentiments were that if he—the only MiG-21 ace—were to be shot down, it would be a “great propaganda victory.”

Home

When Ritchie returned to the U.S., he received the MacKay Trophy for the “most significant Air Force mission of 1972.”

Although he says he garnered respect from a “tight group within the military and military supporters,” he adds that he didn’t escape the contempt that other Vietnam veterans faced.

“I received the anger and was spit on just like other people,” he says. “When I came back, during my very first interview by the Washington Press Corps, it was as if I was being interrogated by the enemy. They were so pro-North Vietnam and so anti-U.S. it was unbelievable.”

Ritchie’s biggest regret regarding Vietnam was the number of close friends who “died for no reason.”

“We were sent to Vietnam and ordered to fight, but we were not allowed to win. That is immoral,” he says, and looks down at the POW/MIA bracelet he wears on his wrist, a remembrance of his backseater and dearest friend in combat, Woodrow “Woodie” Parker II.

On April 24, 1968, Parker, on his tenth mission, was flying with another pilot on a scramble out of Da Nang. The aircraft went down while the men orbited at low altitude over North Vietnam, looking for trucks at night. The flight leader was unable to establish radio contact, no parachutes were observed, and no emergency signal detected. Hostile threats in the area prevented a ground search and rescue operations.

But since there was a possibility that the two men had been able to safely eject; they were listed as missing in action. It would be 30 years before Woodie’s remains would be identified and returned to the U.S. for burial, in 1998.

Ritchie flew to Hawaii to escort his friend back to Washington, D.C.

“I was in first class,” said Ritchie. “They treated me very nicely because they knew my friend was in a casket in cargo. There I was having steak and champagne, and I got to thinking, ‘Why am I in first class getting royal service and my dearest friend is in the cargo section?’ The tears started rolling down my face.”

Parker, buried at Arlington, was honored with a 21-gun salute and an F-15 missing man flyby.

“I spoke at the graveside,” said Ritchie. “It was very sad. His mom and dad are like parents to me; their only son was missing for 30 years for no reason. So many great young Americans and Allies died for no reason.”

Life After The Military

While on active duty, Ritchie was promoted to major, two years early. But, he resigned his commission in 1974 to run for the United States Congress at the prompting of Senator Barry Goldwater, who told him, “We need a lot more people in Congress with military background.”

Ritchie returned to his home district in North Carolina to run.

“I ran as a Republican against a popular Democrat incumbent during Watergate, in the South, right after Vietnam,” he says. “I quickly discovered I’d much rather be flying combat. Because, in combat, the enemy wears a different uniform—not so in politics.”

Ritchie says, obviously, he lost that race.

“We only had 18 percent Republican registration in the six-district North Carolina,” he said, adding he received only about 37 percent total on election day.

“Every day is a plus,” says Brig. Gen. Steve Ritchie, the only U.S. Air Force pilot ace of the Vietnam Conflict.

Much later, Richie helped Cunningham, a good friend, in his successful race for Congress. However, when Bill Armstrong ran for the Senate, Ritchie entered the race for his congressional seat, in 1976.

“I was a carpetbagger in Colorado,” he said.

That experience is another he’d rather forget.

“The Republicans in Colorado treated me worse by a factor of 10 than the Democrats did in North Carolina,” he said. “It was nasty and dirty.”

Ritchie decided to get out of the race. But his experiences with politicians weren’t all bad.

“I was a part of the Reagan administration and knew President Reagan,” he says. “We had two sessions just like this. We talked about the military, politics, flying, combat, philosophy and life. It was an incredible experience.”

In 1976, Ritchie became special assistant to Joe Coors. He held that position for six years.

“It was a great job,” he said. “He’s a tremendous supporter of the military. He was the civilian assistant to the Secretary of the Army for the State of Colorado. Coors won national awards from the Department of Labor for hiring veterans.”

While in that position, Ritchie traveled and spoke extensively on behalf of Coors in regards to the military, our market system, private enterprise, and economic education.

Modern Warfare

Warfare has changed since Ritchie’s day. And he is partially responsible. In a letter to Air Force officials, after he returned from Vietnam, Ritchie and other combat pilots recommended several changes to the way the Air Force trains pilots. One of those recommendations, he said, was the use of aggressor squadrons.

“Soon after that, the Air Force began conducting ‘Red Flag’ missions at Nellis AFB, Nevada,” he said. “Now, we train our pilots using dissimilar aircraft. Our pilots are much better trained and the accident rate is much lower now than it was then.”

Today, Ritchie says, battles are quicker and cleaner, with less collateral damage.

“There are fewer people lost and fewer airplanes downed,” he says. “And, there are more beyond-visual range missiles, remotely-piloted vehicles, smart weapons, etc.”

Ritchie has spent a lot of time with the present day fighter pilots, now flying F-15s and F-16s. He says it’s a thrill to be with them.

“The young fighter pilot of today is really much more advanced than the fighter pilot of yesteryear,” says Ritchie. “These pilots are pulling 9 g’s on a regular basis. That’s very serious work. They have regimented conditioning programs. Diet, sleep, health and exercise—it’s all very important. The kids have to be very educated. It’s not like the old days when there was more of a daredevil-type attitude. Today it’s highly sophisticated. It takes a PhD-type education, high level of discipline, communication, teamwork and understanding of all the systems in the aircraft.

“Not only do you need to have all that knowledge, but you need to be able to employ it under very high-stress conditions—when you’re upside down, when your nose is toward the ground or straight up. It’s called situation awareness, and that’s something that very few people here on earth even understand. It takes a special type of person and it takes a lot of training and expertise.

“I’m with them a lot out there in the fighter squadrons. I flew in an F-16 mission last year at Luke. It was 2 v. 1—two F-16s against an AT-38. I flew in the backseat of the lead F-16 with “Gilligan,” the IP. His student, a lieutenant, was in the other Fighting Falcon. We flew eight engagements at eight g’s each. It was a thing of beauty to witness the way this young captain, 29, led, managed and conducted the mission. As an old guy riding along and watching, I found it very exciting to see these young people performing at such a high level of expertise and knowledge. It makes one so proud of what our folks are doing.”