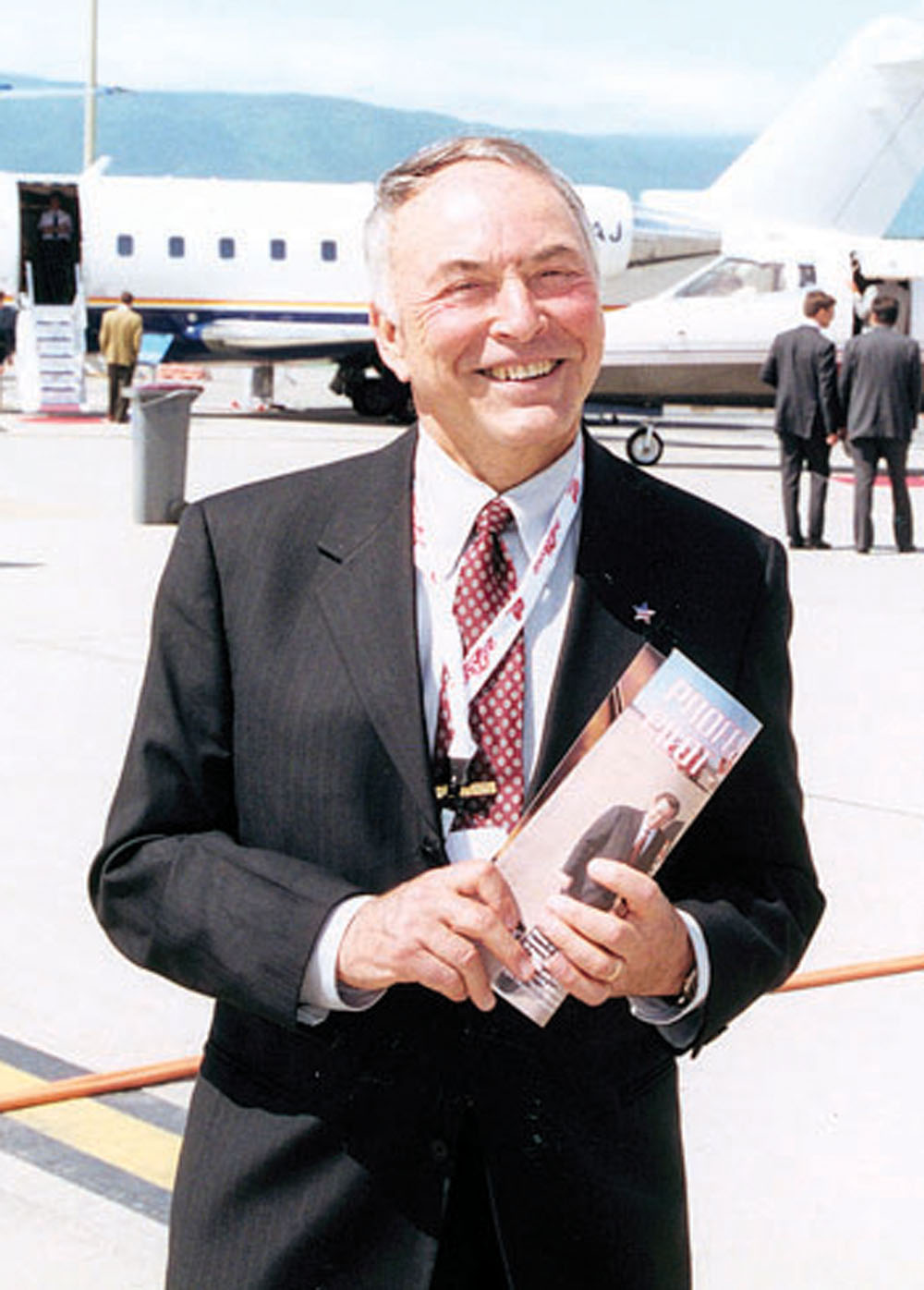

The Writer in the Right Seat – Murray Smith

The first issue of Professional Pilot was published in January 1967. Since then, Murray Smith has never deviated from its values. He has three editorial canons: “accuracy ahead of speed,” “advertising follows readership” and “people are more important than machines.”

The first issue of Professional Pilot was published in January 1967. Since then, Murray Smith has never deviated from its values. He has three editorial canons: “accuracy ahead of speed,” “advertising follows readership” and “people are more important than machines.”

As the editor and publisher of Professional Pilot, Smith is fortunate to be able to use two great talents—writing and flying—on a regular basis. Although Professional Pilot focuses more on the people behind the stick, make no mistake about Smith’s love for the aircraft. It took some severe lessons from an early instructor to balance his passion for the plane with a respect for its limits.

“When I started flying, you had to let the airplane spin, and then you had to roll it out on a point,” he said. “When you did the spins, you had to wear a parachute. The rest of the time, you didn’t. I remember my instructor saying, ‘Murray, I know you just love these airplanes, but don’t get so attached that you ride it all the way down, because this airplane’s a machine; it has no brain. It’s people that make it fly.'”

That’s when Smith began looking at “who” the people in the cockpit are, and when he started combining his love for aviation with writing. Smith, who presently owns a Baron, a Saratoga and a Sundowner, is a certified flight instructor and the only publisher he knows of in this field with a valid airline transport pilot certificate. He believes he spends more time with chief pilots and flight departments then any of his competition. That’s been true since the early days of his magazine, when he began mentioning that he was available to fly in the right seat.

It’s been an interesting road for the gifted journalist. Born in Chicago, he attended Lake Forest College and later, the University of Illinois School of Journalism. He worked for the Leo Burnett Advertising Agency for about a year before he joined the Navy, where he worked as a technical journalist.

He was on his way to flight training in Pensacola when a different opportunity emerged. A commander under Admiral Nimitz invited Smith to join the Navy Chief of Information Office at the Pentagon, where he was inspired to create a new magazine for the general aviation community.

To find out how Murray Smith created one the most popular aviation magazines in the country, read Murray Smith—Squeezing Together a Love of Writing and Aviation. – By Di Freeze

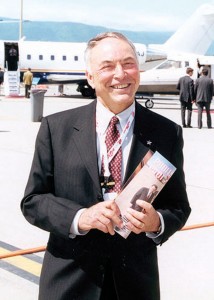

A Rendezvous with History – Paul Tibbets

In January 1927, 12-year-old Paul Tibbets Jr., had his first airplane ride. Sitting in the cockpit of a biplane, he pitched out Babe Ruth candy bars, due to his father’s wholesale confectionary business.

“Nothing else would satisfy me, once I was given an exhilarating sample of the life of an airman,” said the man who, 18 years later, would pilot a bomber to Hiroshima “with a cargo of death instead of chocolates.”

By 1934, he soloed for the first time in a Taylor Cub. However, years before Tibbets discovered his fascination for airplanes, his future had been decided.

“My father had told me, ‘There’s always been a doctor in the Tibbets outfit until I came along; you’re going to be a doctor,'” said Tibbets.

His father enrolled him at the University of Florida. However, the university wouldn’t take him all the way through; it had no medical school at that time.

In 1936, Tibbets was reading Popular Mechanics magazine, when these words caught his eye: “Do you want to learn to fly?” With the advertisement for the Army Air Corps was the address of the adjutant general. Tibbets sent his application in to become a flying cadet, and reluctantly told his father.

“He said, ‘Well, all right. You know, I think I’ve done pretty good by you, so far. I’ve got you this far in school. You’ve got an automobile. You’ve had a pretty good life. But it’s all finished today. If you want to go fly airplanes, go. Kill yourself. I don’t give a damn,'” remembered Tibbets.

Attending basic training at Randolph Field, San Antonio, Texas, he received the highest flying rating. Tibbets was inclined toward flying the fast fighters, or pursuit planes, but a company tactical officer at Randolph advised him otherwise. If he were to fly fighters, once he got through training he would be going into the GHQ (General Headquarters) Air Corps. If Tibbets decided on that, for at least a year all of his flying would be in formation, with someone else deciding where he went and how he got there. However, observation flying would allow him to make his own decisions.

Having an “independent nature,” he asked for observation. That decision was one of the most important of his life; it opened the door to multi-engine flying, an experience that would bring him to “an unanticipated rendezvous with history.”

To read more about Paul Tibbets’ destiny, read A Rendezvous With History. (3 parts) – By Di Freeze

Evelyn Trout got the nickname of “Bobbi” after being teasing by family and friends after bobbing her hair, to emulate stage and screen star Irene Castle. Years later, the tomboy would be a participant in the original “Powder Puff Derby,” the first Women’s Transcontinental Air Race, held in 1929, which led to the creation of the Ninety Nines.

“I’ve always been a little crazy,” says Bobbi Trout. “As a kid, my golly, I wanted a hammer and saw, and I made things! At 4 or 5 years old, I was a carpenter. I hated dolls.”

One spring afternoon in 1918, as she made her way home from school, an airplane passed over.

“It thrilled me to death!” she recalls. “I thought, ‘I’ve got to fly someday!'”

Throughout her life, she blazed her own path. Her pioneering spirit led her to a place, in the 1920s, where just a few fearless women had gone before—the spacious skies.

She took her first flying lessons in 1928, on New Year’s Day, in a Curtiss Jenny. She soloed in April 1928, and was soon flying a four-place International K-6 biplane.

On Jan. 2, 1929, in a flight out of Metropolitan of 12 hours and 11 minutes, she broke an earlier eight-hour endurance record set by Viola Gentry. After Elinor Smith had bettered her record by one hour, on Feb. 10, 1929, Trout set out from Mines Field, returning 17 hours, 5 minutes and 37 seconds later, holding five new records, including the first all-night flight by a woman and the new women’s solo endurance record. One headline read, “Tomboy Stays in Air 17 Hours to Avoid Washing Dishes.”

In the 1930s, Trout instructed and took up photography. Later, during the WWII years, she founded a rivet-sorting company and deburring service. Following that, she opened a real estate office, took a turn at offset printing and opened a life insurance and mutual funds office.

Her thrill seeking throughout the years included motorcycle riding and driving around San Diego County in her red Porsche 914.

We mourned the passing of Bobbi Trout’s death in 2003, but to read more about this wonderful woman’s adventures, read Plane Crazy – By Di Freeze and Dan Miller and Remembering Bobbi Evelyn Trout. – By Di Freeze

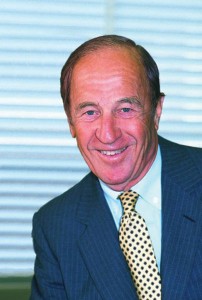

Committed To Good Causes – Steven F. Udvar-Hazy

Steven Ferencz Udvar-Hazy, Airport Journals’ 2005 Lifetime Aviation Entrepreneur award recipient, is the chairman and CEO of International Lease Finance Corp., a $40 billion global aircraft-leasing empire. He’s also the benefactor of the world’s largest aviation museum.

In 1958, shortly after the Soviet Union violently put down the revolution, Hazy’s family left communist Hungary and fled to Sweden. When Hazy was 13, his family emigrated to the U.S.

“We had virtually no material possessions; we lost everything,” he said

At age 18, he started Airline Systems Research Consultants. He mailed letters and telegrams to the airlines, offering them ideas on how they could improve operations.

“Some airlines had too many types of airplanes; I could see that they could consolidate and do things more efficiently,” he said. Aer Lingus, a small government-owned airline in Ireland, became Hazy’s first account in 1966.

When Hazy realized he’d make more money by owning commercial aircraft and leasing them out instead, he and two partners formed a company that would eventually become ILFC. The company revolutionized the way typical leases worked, by introducing a concept now known as the “operating lease.”

By 1983, ILFC was leasing planes to existing airlines and to start-up carriers, after deregulation. That year, the company went public with a $26 million IPO. Seven years later, ILFC merged with American International Group, the world’s leading international insurance and financial services organization. ILFC now has more than 800 aircraft in its fleet.

Hazy, who has earned his multi-engine, instrument and commercial ratings, has a love for aviation that extends way beyond leasing commercial aircraft or flying aircraft. That love was one of the reasons he gave the Smithsonian $60 million, which was the institution’s largest donation to date, for the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.

Located near Washington Dulles International Airport, the center is the companion facility to the Museum on the National Mall. It opened in December 2003, and provides enough space for the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum to display the thousands of aviation and space artifacts that can’t be exhibited on the National Mall. The two sites together showcase the largest collection of aviation and space artifacts in the world.

“I felt in my heart it was the right thing to do, for our country that gave me so much,” he said.

To read more about Steve Hazy, read Steven F. Udvar-Hazy: Committed to Good Causes. – By Di Freeze

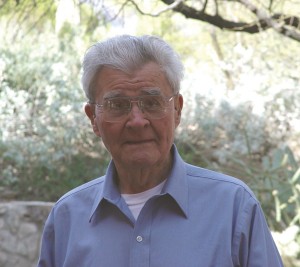

Saving Lives & Saving Sight – Al Ueltschi

A.L. Ueltschi is the founder and chairman of FlightSafety International, the world’s largest provider of aviation services and training. The company’s mission is helping its customers in their quest for safe, reliable transportation.

Ueltschi says the best safety device on any aircraft, anywhere, remains a well-trained pilot. More than 75,000 pilots, technicians and other aviation professionals train at FlightSafety facilities each year. The company designs and manufactures full-motion flight simulators for civil and military aircraft programs, and operates the world’s largest fleet of advanced full flight simulators at more than 40 training locations.

Ueltschi is also the chairman of ORBIS International, an international nonprofit organization dedicated to saving sight and eliminating unnecessary blindness worldwide. Through the work of the organization, more than a million people have received direct medical treatment. More than 93,000 healthcare professionals have enhanced their skills through ORBIS programs in more than 80 countries.

After four years in a single-room schoolhouse in Choateville, Ky., Ueltschi transferred to a school in Frankfort. Nothing he learned in school was as fascinating as the stories he loved to read about the pilots of the day and the aircraft they flew.

“I loved airplanes from the very beginning,” he said.

Ueltschi will never forget the excitement he felt when Charles Lindbergh made his historic flight across the Atlantic in 1927. He listened intently to the radio for any report on the flight; he knew with certainty he would be a pilot, too.

“I’d follow my father around and tell him what I was going to do,” he said. “He probably thought I was a little nuts, but he never discouraged me. When Lindbergh flew the Atlantic, I told `him, ‘Now, dad, I’m really going to be a pilot.’ He said, ‘Al, you are a pilot.’ I said, ‘What do you mean, I’m a pilot?’ He said to me, ‘You pile that cow manure over here and pile it over there; you’re a pile-it.'”

Ueltschi did become a pilot, and he’s accumulated more than 35,000 hours of flight over the years. His career has included flying for Juan Terry Trippe, the founder and CEO of Pan Am.

To read more about Al Ueltschi, read Saving Lives and Saving Sight. – By Di Freeze

Still Thrilling Crowds – Patty Wagstaff

Patty Wagstaff is a three-time U.S. national aerobatics champion and internationally acclaimed air show pilot. These days, she’s also dedicated to helping preserve wildlife in Africa, while assuring the safety of the pilots who protect them.

For several years, Wagstaff and a friend have traveled to Africa to provide aerobatic and recurrency flight training for pilots of the Kenya Wildlife Service. Wagstaff, who first earned her flight instruction certificate when she was a bush pilot in Alaska, feels that her work in Kenya is probably the most interesting thing in her life right now, except for keeping up with her air show schedule.

“These Wildlife Service pilots patrol in all the national parks in the country and are the biggest single deterrent to poaching in Kenya,” Wagstaff said.

In a desire to challenge herself, Wagstaff was drawn to aerobatics and competition flying. She continues to perform regularly throughout each air show season.

Although Wagstaff’s father was an airline pilot, and her younger sister chose the same profession, she didn’t earn her pilot’s license until she was in her late 20s. She said that her free-spirited, “gypsy” nature pulled her in other directions at first, and that she didn’t have the opportunity to fly growing up. But frequent moves, part of an airline pilot’s life, plus her desire to live apart from her family as she struggled to find her life’s path, delayed Wagstaff’s plunge into the world of aviation.

It was Bob Wagstaff, a pilot with a flight instructor rating whom she met in Anchorage, Alaska, who really introduced her to the pleasures of flight. She said the instant she took the controls, she knew exactly what she wanted to do with her life. Flying added true meaning to her life and it gave her a new attitude. She found that it was something that allowed her to be herself—something at which she could excel. She looked at aviation as the “great equalizer.”

“There was equality at the yoke in the cockpit,” she said.

To read about Patty Wagstaff’s journey, read Patty Wagstaff—Still Thrilling the Crowds. – By Di Freeze and Chuck Weirauch

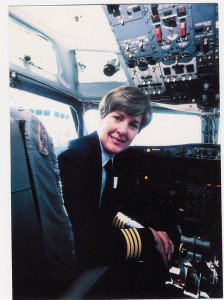

Conquering A Male Dominated Industry – Emily Howell Warner

Emily Howell Warner paved the way for female pilots in 1973, when she became the first woman hired as a pilot (in modern times) by a U.S. scheduled airline carrier.

After piloting a Boeing 737, in 1974, she became copilot of the de Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otter, becoming Frontier’s first female second-in-command pilot on a DHC-6. That same year, she became the first female officer at Frontier to copilot a Convair 580. Again flying the DHC-6 in 1976, she became the first female captain of a U.S. airline carrier. Eight years later, she became the first Frontier woman captain to fly the 737; during that year, while captain of the 737, she commanded the first all-female crew.

After Frontier broke barriers by hiring Howell Warner, other airlines followed suit, giving women the chance to follow their dreams of flight. But Howell Warner’s path wasn’t easy.

The Colorado native was working at the May Company when she landed a job at Clinton Aviation, a local fixed base operation. The information wasn’t good news for her boss, who had been training her to be an assistant buyer.

“Oh Emily, you’re going to give up a good career in the retail business!” she lamented.

While at the May Company, the 18-year-old often waited on “stewardesses” who would come in on their day off or on breaks. She thought that would be something she’d like to do, but was disappointed when she found out that the minimum age requirement was 20 and a half, since they served liquor.

In the meantime, an acquaintance suggested she take a flight to see how she’d like it, since she’d never flown.

“I bought a ticket on Frontier Airlines in a DC-3,” she said of her first flight to Gunnison, Colo., early in 1958. During the flight, she watched the stewardess’s every move, and since she was the sole passenger on the weekday flight back, she asked if she might be able to see the cockpit.

“In those days, security hadn’t come into play yet,” she said. “I got to ride on the jump seat back to Stapleton.”

She was happy when she didn’t get airsick. In fact, she loved the flight. She was hooked.

To find out what it took for Emily Howell Warner to enter the cockpit, read How Emily Hanrahan Howell Warner Conquered the Male-Dominated Airline Industry – By Di Freeze and “Weaving the Winds”. – By Henry Holden

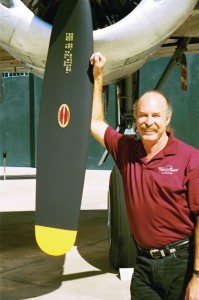

The Fantasy of Flight – Kermit Weeks

Kermit Weeks loves to fly airplanes. He also sees the magic of flight as a powerful tool to educate the masses.

Weeks has always been interested in working and designing machines. Eventually this mechanical interest melded with his love of aviation to help him develop a keen desire to build airplanes. Constructing a kit aircraft was a logical step. His first introduction to the homebuilt movement grabbed his attention and allowed him to develop several aircraft designs.

At age 17, he began construction of his first homebuilt aircraft, which he flew four years later. He flew his second airplane, the Weeks Special, in competition.

After getting his primary flight training out of the way, he decided to add a bit of excitement to his flying through aerobatics. With some friends, he decided to teach himself how to fly. Without an aerobatic instructor to walk them through the maneuvers, the group opted for the next best thing—Duane Cole’s famed aerobatic text, “Roll Around a Point.”

“We practiced all the basic maneuvers at safe altitudes, although slow rolls took us a little longer to master,” Weeks admits.

During his sophomore year of aeronautical engineering at Purdue University, Weeks decided school wasn’t for him, so he quit, finished his Weeks Special design and trained for aerobatic competition. In 1977, at age 24, he made the U.S. Aerobatics Team. In 1978, he won three silver medals and one bronze in the World Aerobatics Championships held in Czechoslovakia. Over the years, Weeks placed in the top three in the world five times, while winning many other contests, including two wins at the U.S. National Aerobatics Championships and several Invitational Masters Championships in different worldwide competitions.

During the late 1970s, Weeks attended a couple of air race events in the Miami area and marveled at the variety of warbirds flying. That’s when he decided he wanted a P-51 Mustang. However, his first aircraft was actually a T-6 Texan.

“I really didn’t want the T-6, but I knew that’s what World War II pilots used to train in before moving into the P-51,” he explained.

He did get his P-51, as well as other aircraft. He soon realized the increasing need to house his aircraft in a large facility. He also wanted to provide aviation enthusiasts the opportunity to enjoy viewing the aircraft. In 1980, he drafted plans for what would be called the Weeks Air Museum.

To read more about Kermit Weeks and the Weeks Air Museum, read Kermit Weeks, Snoopy and the Fantasy of Flight

– By Arturo Weiss

The High Flying Cable Guy – Carl Williams

At the office of Carl M. Williams & Associates, Inc., at the Denver Tech Center, pictures and models of aircraft, as well as many reminders of his rich past, surround this cable pioneer. Although he has a busy day ahead of him, the Colorado Aviation Hall of Fame enshrinee relaxes and talks about some of his favorite subjects: aviation, family, ranching and the cable industry.

Williams, a third-generation rancher, grew up on a 33,000-acre ranch in Douglas, Wyo. During the years after World War I, his father, who was in the Navy Reserve, turned over the job of running the ranch to his children. While one son was serving in the military, at the age of 13, Williams had the entire burden of running the ranch. He attended school regularly, but like other children in the ranching community during the war years, he was released in early spring to attend to the family ranch.

In between school and working the ranch, Williams, who dreamed of one day owning his own business—or several—was busy reading a book. He devoured every word of “Think and Grow Rich,” by Napoleon Hill.

During that period, he also had his first airplane ride. Shortly before he was born, his father had become a pilot and had sold 30 heads of steer to purchase an OX-5 long-wing Alexander Eaglerock. He quit flying after the aircraft crashed into a livestock barn at the state fair in 1927. Still, he was willing to arrange for his son, who had seen pictures of the Eaglerock, to have his first ride in a Cessna 120 at Cheyenne Municipal Airport in 1941. Williams loved it.

Shortly after Williams’ father was assigned to the staff of the adjutant general in Cheyenne, Wyo., he convinced his commander to return him to sea duty. Since he was stationed in Monterey, Calif., the family packed their bags, leased the farm out, and left for California.

As a high school sophomore, Williams made many visits to the air base and had the opportunity to sit in the cockpit of the combat planes and “fantasize.” Life’s choices were starting to get complicated: rancher, businessman, fighter pilot? Williams wanted to do it all, but at that age, didn’t think it was possible.

“At 13 or 14, you don’t know what you want to do, or can do,” he said.

To find out how Carl Williams made a name for himself in the cable industry, and within the field of aviation, read The High Flying Cable Guy. – By Di Freeze

Booming & Zooming – Chuck Yeager

Unlike many aviators Chuck Yeager would meet throughout his life, he never dreamed of flying while he was growing up in Hamlin, W. Va., in the Appalachian foothills.

“I run into guys that say, ‘I hung on a fence, and I looked at airplanes; I wanted to be a pilot,'” he said. “Hell, airplanes meant nothing to me, because I didn’t know what they were. Even after I got into the military in ’41, at age 18, I was just a mechanic, and flying—I just wasn’t interested in it. It wasn’t my world.”

His “world” was doing whatever he enjoyed. It helped that what he enjoyed, he did well.

Charles Elwood “Chuck” Yeager was born in February 1923, in Myra, W.Va., a small town a few miles up the Mud River from Hamlin. In September 1941, an Army Air Corps recruiter caught Yeager’s attention and the 18-year-old signed up for a two-year hitch, thinking he might enjoy the military and get to see a little of the world.

In 1941, while stationed at Moffett Field, San Francisco, Calif., as an airplane mechanic, Yeager saw a notice regarding the Army Air Corps’ Flying Sergeant program.

“Cadets had needed two years of college, and had to be 20 years of age,” Yeager said. “They weren’t getting enough applicants, so they opened it up for aviation students; that’s what they called us, instead of cadets. Basically, if you had a high school diploma and were age 18, you could apply for pilot training, but you wouldn’t be an officer when you graduated; you’d be a staff sergeant.”

Yeager still wasn’t interested in flying, but the deal sounded inviting.

“We were busting our knuckles working on airplanes,” he explained.

At that point, Yeager had never flown.

“I finally took a ride at Victorville in an AT-11 twin-engine bombardier trainer that I was crew chief on,” he said. “Man, I puked all over; I was so sick. When I landed, I said, ‘Yeager, you made a big mistake!'”

Yeager was called for pilot training in the summer of 1942.

“When I started flying the airplane, instead of just riding in it, I had no problem,” he said.

What he eventually did have, was lots of excitement.

To follow Chuck Yeager’s history, including combat and evasion, 13 aerial victories and breaking the sound barrier, read Booming and Zooming (2 parts) – By Di Freeze