By Di Freeze

Charles Taylor, the designer and builder of the engine that powered Wilbur and Orville Wright’s craft on Dec. 17, 1903.

Aviation maintenance technicians, the unsung heroes of aviation, are finally getting long overdue recognition—at least in California, with the recent proclamation of May 24 as Aviation Maintenance Technician Day.

Choosing that date was easy—it’s the birthday of Charles E. Taylor, the designer and builder of the engine that powered Wilbur and Orville Wright’s craft on Dec. 17, 1903.

Since the early 1990s, the Federal Aviation Administration has sponsored the Charles E. Taylor Master Mechanic Award, which recognizes aviation maintenance technicians with over 50 years of documented distinguished service in aircraft maintenance (30 of which must be as a FAA-certificated aircraft mechanic or repairman).

With the FAA already acknowledging aviation maintenance technicians, it was only natural that representatives of the organization would be at the forefront of the successful push for Aviation Maintenance Technician Day. But there were others as well.

The Aviation Maintenance Career Commission, founded in September 1999, has the vision of seeing that next year’s celebration of 100 years of flight will include worthy mention of those involved in aviation maintenance.

The AMCC includes representation from Embry-Riddle as well as the Professional Aviation Mechanics Association and the North Carolina Historical Society. The commission has been brainstorming ideas, including a memorial to the “Father of Aviation Maintenance,” which has a target dedication date of May 24, 2003. The memorial should be created at Wright State University, in Dayton, Ohio, with a second hoped-for memorial on the West Coast.

Officers of the commission include Mike Mulcare, president, who is retired from Delta Air Lines. Phil Randall, safety program manager (airworthiness), Greensboro, N.C., is the chairman of the FAA board of advisors, on which Richard Dilbeck, safety program manager (airworthiness), Sacramento Flight Standards District Office, also sits. The Honorable John Goglia, National Transportation Safety Board, Washington D.C., serves on the commission’s board of trustees.

Serving as a member of the NTSB since August 1995, Goglia, with 30 years experience in the aviation industry, is the first board member to hold an FAA aircraft mechanic’s certificate. His interest in Taylor’s history led him to call Giacinta Bradley Koontz, at the time director of the Portal of the Folded Wings, Shrine to Aviation, where Taylor is buried, and ask for a tour.

As director and an aviation historian, Bradley Koontz researched the history of those buried at the Portal.

“As I was doing that, I interfaced with Howard DuFour, a machinist who had this fire in his belly to write the life story of Charles Taylor,” said the Burbank resident.

DuFour, 86, led the volunteer effort, made possible by grant funding, of creating a full-scale replica of the 1903 “Wright Flyer” that is suspended in the atrium of the Paul Laurence Dunbar Library at Wright State University. Begun in the fall of 1999 and accomplished in two years through 4,000 volunteer hours, the project had been DuFour’s dream since he first became fascinated with the engine construction of “The Flyer” two decades ago.

Prior to that, after years of research, DuFour, with Peter Unitt, published “Charles E. Taylor: The Wright Brothers Mechanician,” in 1997. Bradley Koontz utilized the book to create a display that was shared with Goglia on his visit.

His interest in Taylor further enhanced, Goglia has been campaigning for recognition for Taylor, including talks with the post office regarding a stamp.

In August 2001, Bradley Koontz held a reception at her home to honor Goglia and others. Richard Dilbeck attended the reception.

“He had the same passion to do something to honor Charles Taylor,” Bradley Koontz said. “He flew down from Sacramento specifically to meet John Goglia and to see Charles Taylor’s grave.”

Dilbeck, with the FAA for about five years and bearing his present title for about three, credits a round black and white TV set he watched back in rural Iowa when he was a child with getting him involved in aviation. Although he was fascinated with “Sky King,” he was more fascinated by the action centered on a helicopter in “The Whirlybirds.”

After graduating from high school, in 1970, Dilbeck entered the Air Force and was soon able to fulfill his dream of working on helicopters at a top-secret base in Nevada. Later, when a friend took a hardship leave from the Air Force, Dilbeck helped him moved back to Ohio. They visited Dayton in the mid-1970s, including Wright Patterson’s museum and the famed bicycle shop. The trip to Dayton would long be remembered.

Years later, Dilbeck began campaigning to “show the world there are a lot of folks that don’t get pats on the back like pilots do.”

“I have a passion to get the recognition out there and see these unsung heroes memorialized before they pass away to that big hangar in the sky,” Dilbeck said.

At the reception, and at other times, Dilbeck and Bradley Koontz discussed what could be done to earn Taylor and aviation mechanic technicians recognition. One idea was to have a proclamation drawn up like Bradley Koontz had done to honor early aviator Harriet Quimby recognition.

“I did some Internet exploring and came up with some drafts,” Dilbeck said. “I also made contact with some of the legislation folks under Governor Grey Davis and was able to convince them of the plight of the unsung heroes of aviation. They handed it down to somebody that I suggested, which was Senator Pete Knight, a retired Air Force colonel and test pilot out of Edwards Air Force Base who flew the X-15, whom I was sure would know the importance of aviation maintenance folks.”

L to R, front row: Richard Dilbeck and wife Cheryl; Giacinta Bradley Koontz; Sen. Pete Knight; Tamara and Greg Michael; William Withycombe; and Larry Kephart. L to R, back row: Mrs. Prothero and Ed Prothero and Phil Randall (in gold shirt)

Although Dilbeck continued his work on the draft, he says Knight “took the ball and ran with it.” Out of the loop temporarily, a surprised Bradley Koontz later received a letter from Knight asking her to attend a ceremony in Sacramento.

“Pete said, ‘To heck with a proclamation; let’s just go for a bill and make it Aviation Maintenance Technician Day in the state of California for now and forever on May 24,'” Koontz said.

On April 25, Knight introduced resolution SCR 70 in a session of the California State Senate, in Sacramento. Those in attendance or introduced on the floor included Bradley Koontz, Phil Randall and Dilbeck, and Bill Withycombe, the FAA’s Western Pacific regional administrator; Larry Kephart, FAA division manager (who also has a maintenance background); and Greg Michael, manager of the Sacramento FSDO. Goglia and DuFour were unable to attend, but were invited and recognized.

The resolution specifically mentions Taylor’s building of the Wright’s first engine.

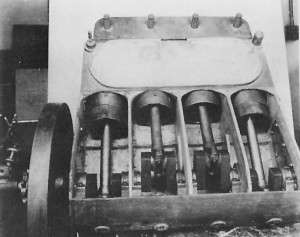

“It explains engine theory and using the drill press and a lathe to make a four-cylinder engine weighing 179 pounds producing 12-horsepower, in six weeks,” Dilbeck said. “That’s a remarkable accomplishment. It couldn’t have been done without Charlie. Basically, the Wright brothers had a very nice glider and then Charlie pounded out an engine.”

The bill passed unanimously and did so again in May when it went before the Assembly. A few days later, Sen. Knight signed the proclamation. Dilbeck is rightfully proud that California was the first state to put a resolution of this type into action.

“My competition are friends of mine back in Ohio and North Carolina,” he said. “We beat them to the punch at Kitty Hawk, where history was made, and in Dayton, Ohio, where Charlie made the engine.”

FAA’s Western Pacific region covers Nevada, Arizona, California and Hawaii. Verbiage in the resolution, however, states that California in particular will celebrate Aviation Maintenance Technician Day.

“Probably the Western Pacific will harness those other states,” Dilbeck said. “I’m meeting with the other safety program managers that cover those states, and asking them to go back to their Senate staff to ask that state to buy into this.”

The Memorial

A lot of thought has gone into the memorial championed by the AMCC. Information on that project can be accessed at www.amccommission.com, where an artist’s rendition of the memorial can be found. The memorial foundation is shaped like a six-sided bolt head. In the middle of the memorial will be an image of Charles Taylor, working on his engine, complete with his history, and the logo of the aviation maintenance technicians, which combines images of the space shuttle and the “Wright Flyer.”

Behind the image of Taylor will be a structure similar to the Vietnam Wall, displaying names of Charles Taylor Master Mechanic Award recipients.

Bricks in the middle of the foundation can be purchased at $50, with half going towards funding the building of the memorial and the other half towards costs associated with quarterly newsletters, etc. The bricks will bear the name of the individual or company that donated funds.

“On a larger scale, we’re looking for corporate backing as well,” Dilbeck said. “One company has already bought all their employees half the price of the bricks. They come up with the other half. Delta has bought a section.”

It is speculated that in future years, Charles Taylor Award recipients will be honored the week of May 24. At that time, their name would be engraved in the wall.

Although very interested in that project, Dilbeck, Bradley Koontz and others are striving for a memorial in California.

“The East Coast has Kitty Hawk and they have the Smithsonian,” said Bradley Koontz. “Dayton, Ohio has the Wright Brothers’ bicycle shop. On the West Coast, people are hard pressed to distinguish a spot where people honor early aviation, like they do with WWII, private aviation and the aerospace industry.”

Bradley Koontz says that they can’t build a memorial where Taylor is buried because the Portal is privately owned. Dilbeck thinks that the North Hollywood/Burbank area is a likely candidate for “Kitty Hawk West.”

Charles Taylor

Charles Taylor was born in 1868. By 1901, he was living about six blocks from the Wright brother’s bicycle shop. He began working for the Wrights in June of that year, tasked with taking care of the bicycle business, while Orville and Wilbur concentrated on their flying studies and experiments. He was their only employee for eight years.

When the Wright brothers decided to build a small wind tunnel to test out some of their theories on wings and control surfaces, Taylor helped with the project. Later, the brothers announced that they were finished with gliders and wanted to try a “powered” machine. They began work on a craft, larger than previous gliders, in order to carry an engine. When they couldn’t locate a suitable engine, they decided to build their own. The job fell to Taylor, although his previous experience was only with repairs of an automobile’s gasoline engine.

With no drawings to follow, they sketched their own. Soon, a crankshaft emerged from a block of machine steel 6 by 31 inches and 1 5/8 inch thick. The body of the first engine was of cast aluminum bored out on the lathe for independent cylinders. The pistons were cast iron.

Taylor also constructed metal parts needed for the airframe of the craft.

After block testing, the engine was crated for its shipment by train to Kitty Hawk. Taylor stayed behind to run the shop once again.

He learned by a telegram sent to the Wright brother’s father that they had made four successful powered flights. With the engine damaged on the fourth flight, when a heavy wind picked up the aircraft and turned it over, Taylor went back to work.

Taylor built about a half-dozen engines for the Wrights before they formed their airplane company in 1909 and added additional help. He was put in charge of the engine shop.

Taylor continued with Orville after he sold the company in 1915, helping him with inventions and experiments, as well as keeping his car in good running order. His faithfulness earned him an $800 annuity in Orville’s will.

Taylor next went to work for the Dayton Wright Company, where he piloted aerial photographers, in a Dayton Wright FP-2 seaplane, into Canada.

In the late 1920s, he moved to California. He worked in a machine shop in Los Angeles until the Depression put him out of work. With money he had saved, he invested in 336 lots in a new land development on the edge of the Salton Sea, in the southern California desert.

Henry Ford hired Taylor in 1937 to help restore the original Wright home and shop moved to his Greenfield Village Museum at Dearborn, Mich., installed near the first Ford workshop and Thomas Edison’s original laboratory. At that time, Taylor built a replica of the first Wright engine. He died Jan. 30, 1956, at the age of 88.

Information regarding Charles Taylor can be found at [http://www.portalofthefoldedwings.com].