By S. Clayton Moore

The fire retardant used by the bombers leaves behind a slippery red dye, which can be tricky for line firefighters.

One of the crucial ingredients in the fight against Colorado’s wildfires is based at Jefferson County Airport. The air tanker base, which is operated by the United States Forest Service, has been busy since the beginning of summer dispatching slurry bombers, the fixed-wing aircraft used to bombard mountain wildfires with fire retardant.

“Last week was great. It was controlled chaos,” said Mark Michaelson, 33, the air base manager for the Forest Service facility. It’s Friday, May 3, a week after the bombers were instrumental in extinguishing the Snaking Fire, which burned over 2,500 acres near Bailey, Colo.

The base has a great view of a dangerously dry Front Range that faces a summer with a low snow pack, high winds, and drought conditions. As the pilots and crew look out over Colorado’s mountains, the consensus is that they’re going to be busy again soon.

“We’re going to fly today. I can feel it,” says Michaelson. The pilots agree with his judgment. Maybe not today, but the pilots are sure they’ll be flying again by the weekend. Within 48 hours of Michaelson’s prediction, the crews of the slurry bombers are pounding the Black Mountain fire near Evergreen, trying to contain it with a perimeter of retardant. Ultimately the fire would burn nearly 400 acres and scorch the mountain within a quarter mile of the subdivisions that dot the ridge.

“I get kind of jumpy for fire season. I can’t wait for it to end, but at the same time, I can’t wait for it to start again,” said Michaelson, who has 12 years of experience in emergency medical services as well as working as a wild land firefighter in the Montana backcountry. “That’s when all the action starts and the magic begins.”

“It’s a good job. We’re really glad to be able to be here and fight these fires, especially in conditions like you have here. Unfortunately we’re expecting to be pretty busy,” said Gordon Koenig, a pilot for Hawkins & Powers Aviation out of Greybull, Wyo. About 42 air tankers are under contract around the country to fight fires. Each year, Michaelson is responsible for contracting for air tankers and pilots like Koenig with a number of aviation services, as well as caring for the aircraft, pilots and facilities during the season. It’s no small feat.

“There’s a lot of different issues, variables, and scenarios that are constantly playing through my head,” said Michaelson, who was on his twenty-first consecutive day of duty by the time the Black Mountain fire was contained. “If we get a big firebreak today, there’s a lot of questions to go through. How big is the fire and how fast is it spreading? How many air tankers are we going to be using? Are more air tankers going to fly in? I have to look at how much retardant I might fly. I have to look at the weather.”

Jeffco’s supply of retardant, or slurry, weighs in at about 12 pounds per gallon, and is housed in three 12,000-gallon tanks. The retardant is comprised of a number of different compounds including ammonia polyphosphate fertilizer, a corrosion inhibitor for the aircraft tanks, and a series of clays that help keep the retardant in suspension as it drops. The ground crew uses high capacity pumps to produce a five-to-one ratio of water to liquid concentrate retardant.

Iron oxide is also added to provide the shocking red color that permits pilots flying in dense smoke to view their drop patterns. Great caution is used to avoid ground crews; one 18,000-pound load can knock down trees and potentially roll vehicles. The slurry load leaves behind phosphorus from the fertilizer component, as well as the marker dye. The remains can be exceptionally slippery for line firefighters.

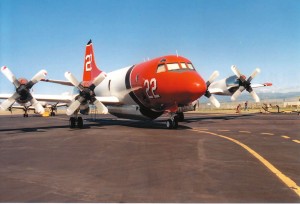

This P-3 Orion aircraft was originally built by Lockheed for the U.S. military before being converted for use as an air tanker.

Michaelson’s crew has the task of rearming the bombers with retardant down to a science. A single-engine air tanker can be loaded with 800 gallons of retardant within a minute and a half. Larger planes like the converted B-24 and P-3 aircraft can carry up to 3,000 gallons yet still take less than six minutes to refill.

Michaelson often gets a heads-up about fires from the regional coordination centers.

“If I do get the heads-up before an order is placed through the dispatch system, I can already have pilots notified and the air tanker filled and ready to go. As soon as we get that official order from dispatch, all the pilots have to do is turn the props and they’re gone,” said Michaelson, who can have multiple air tankers airborne in as little as 15 minutes from the time he receives a request for aircraft support.

“It’s a different lifestyle,” said Koenig, who makes his home in the state of Washington. At the controls of the aircraft are contract pilots who work for Hawkins & Power, Aeroflight, Butler Aviation, and other air tanker services. The pilots move around the country with their location depending on where the fires are burning. “You’re definitely an itinerant laborer. You move from place to place and you can never predict where you’re going to end up. We chase the fires. That can get old, but it goes with the territory. Once the season’s over, you can breathe a little easier.”

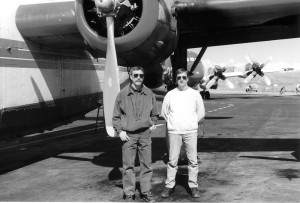

It’s not easy, however, for Koenig to maneuver the aircraft that he flies along with co-pilot Mike Flynn. Koenig’s PB4Y2 is the U.S. Navy version of the B-24 bomber. Many of the aircraft, which include B-24, P-3, C-130 and DC-7 as well as the PB4Y2, are former military planes. The PB4Y2 on the field today was built for submarine patrolling during WWII, used by the U.S. Coast Guard during the 1960s, and then converted for use as a slurry bomber by Hawkins & Power.

Pilot Gordon Koenig flies the converted B-24 behind him with co-pilot Mike Flynn, right. The two pilots fly as close as 100 feet above the tree line to deliver their payload.

“It’s a lot of work compared to smaller and more modern aircraft. All of our controls are cable controls, so it’s quite a grunt to get the aircraft to do what you want it to do,” said Koenig.

Of the process for coordinating firefighting efforts in the air, Michaelson says there are a lot of players in the game. Once on site, the bombers contact the air attack plane, which is the in-flight coordinator over the fire, and then circle between 1,500 and 3,500 feet.

“There’s a whole different science to dropping the retardant,” he says. “When it’s applied correctly and effectively, it works great. It’s actually up to the air tacs (tacticians) and pilots, or the coordinators on the ground to decide the coverage level, whether it’s heavy or light. They tell us exactly how they want it dropped and that’s how we set it down.”

The air tankers, which only fly during daylight hours, are allowed to make their flights up to one half hour before or after sunset, providing an air attack plane is on site.

“We drop at 120 knots. You really have to be paying attention at all times,” said Brad Baker, a copilot on an Aeroflight P-3 that carries up to 3,000 gallons of retardant. The bombers make their runs just over 200 feet above the tree line. “If you’re going a little fast, flaps up, and you’re getting rid of 18,000 pounds, it can go in two-tenths of a second. It’s a pretty good pitch-up, but it’s nothing you can’t correct.”

Michaelson opened the tanker base early, on April 1, after seeing bad signs for this year’s fire season, during a visit to the Pueblo base.

“This year I just got a really weird feeling,” he said. “All of a sudden, they had three fires. When you get a red flag warning, we’re looking at high winds and really low relative humidity. Once you get into single digits, it’s bad news. I was down there, and they were getting red flag warnings at 9:15 in the morning.”

Michaelson rushed back to Jeffco to order retardant and prep the base for tankers.

Air base manager Mark Michaelson pauses in front of the huge P-3 Orion air tanker at Jeffco Airport. Michaelson is currently the only fulltime staff member on the base year-round.

“I was definitely making preemptive movements to get the base open,” he said. So far this year, the base has pumped 176,000 gallons of retardant.

“You can’t really prevent the fires, no matter what you do,” said Michaelson, who has no worries about job security during this dry year. “Things are going to happen whether it’s something intentional or not. Trains spark in the mountains, and there’s always lightning. There are a lot of different factors out there. At the same time, if people just use common sense, we can probably keep it down.”

Troy Stover, acting airport manager at Jeffco, who works with the base to ensure the county meets its needs, says that when the fire season begins, they change their operations a little bit.

“We look at security and a media area to make sure things are being done safely,” he said. Stover has also made room for local residents, who have appeared in lines of 15 cars or more to watch the planes refuel, rearm and take off. “We have people coming out with their lawn chairs and their lunches. They love watching them. It’s like a mini-airshow.”

Local resident Geneva Henry stopped by that day.

“We just wanted to see the operation,” Henry said. “The planes have been flying over our home for four days. They’re doing the job for us, you know.”

Michaelson laughs.

“Tanker groupies,” he says, as he waits for the next air tanker to arrive at the air base. “I love it. We have tanker groupies.”