By Di Freeze

With a little more than 17,000 flight hours, including time spent in Southeast Asia and corporate flying, Bob Pardo says he’ll never have as much flying time as a lot of other people.

Shown as an Air Force cadet in 1954, Bob Pardo developed an interest in aviation as a youth. His family was living in Hearne, Texas, when a pilot with a Taylorcraft opened a small grass strip.

“That’s not a lot compared to my airline buddies,” he said. “But I’m not trying to break any records. I just love to fly.”

Born in North Central Texas, in a small town of about 3,500 people, just outside Waco, the fourth of five children born to Roland and Lucille Pardo says his family was “quite poor,” but never went hungry. Pardo’s grandfather, a truck farmer who raised vegetables, etc., trucked them to market. During World War II, when the town was home to a prisoner-of-war camp, Pardo’s family faced tough times, but did so by raising their own vegetables also, as everyone was encouraged to do.

“We’d dig up lawn and put in a garden,” he said. “My dad was always winning best garden of the month and best lawn. Our meat supply was supplemented with wild game.”

The Pardo family moved to Hearne, Texas, when Pardo was seven. Five or six years later, he watched as a pilot with a Taylorcraft opened a small grass strip. It wasn’t long before he took a ride, and decided to learn to fly. He and his older brother, Louis, worked at the airport mowing grass, washing airplanes and digging drainage ditches alongside the runway in turn for a few unrecorded flying lessons.

Eventually, after the pilot had taught all who were interested in the little town, business dropped off and he moved on to another. Pardo’s attention turned back to school; working with his father in the summer for the Lone Star Gas Company in the pipeline department, repairing leaks, installing measuring stations, etc.; and his involvement with sports such as football, baseball, basketball and track.

During his junior year in high school, the running back and linebacker attracted the attention of scouts for different colleges in the Southwest Conference. But Pardo had already decided he wanted to go to Texas A&M, 20 miles from home. However, his hopes of obtaining further glory in that sport were dashed when in his first game of his senior year he tore up his knee.

After graduating from high school, he worked for a seismic company, looking for oil. That was fun for the summer, but Pardo knew there was a bigger world than what he had seen. With an offer of free room and board from his sister and brother-in-law in Houston, Pardo entered the University of Houston. To make ends meet, he took various jobs on campus, in the laundry and mailroom, as well as on the switchboard, which left little time to study.

“That year was literally a waste,” he said. Then, he briefly worked with his dad on the pipeline again. At the beginning of 1954, a buddy tracked him down and they continued earlier discussions about getting into Navy or Air Force cadets.

“I have a very strong appreciation of what we have in this country and where it came from,” Pardo said. “Most of the men in our family served in the military at one time or another. Dad was in the National Guard. My uncle was in the Army, and my oldest brother served in World War II. My other brother served during Korea. A few men in the family made a career in the military.”

When they first began discussing a military future, requirements had been lowered to two years of college, instead of four. But, Pardo didn’t see how he was ever going to get two years at that point in his life. Then, the Air Force lowered their requirements to a high school diploma. Pardo, at the time 19, joined up and qualified for pilot training.

He took primary training at Spence Air Force Base in Georgia, starting in the Piper PA18 Super Cub, and then going to the North American T-6. Basic training was at Bryan AFB in Texas, about 20 miles away from home, where Pardo progressed from the T-28 to the T-33 jet trainer. He made his first jet landing in his hometown, at an auxiliary strip at the disposal of the Air Force.

Out of 550 students in his class, at two or three different bases, only eight were selected to go to fighters. Pardo went to Del Rio, Texas, to Laughlin AFB, for phase-one gunnery school, continuing to fly the T-33.

“We were already familiar with the airplane; the only thing new was the gunsight,” he said.

There, they learned about bombing, aerial gunnery, air-to-ground gunnery, rockets, etc. Then, it was on to Luke AFB in Arizona for phase-two gunnery.

In 1955, just before turning 21, Pardo flew his first supersonic aircraft. However, he says the swept-wing Republic F-84F Thunderstreak wasn’t that “supersonic.”

“You had to climb to about 40,000 feet, roll over and come straight down full power, and then, at about 20,000 feet, it would go supersonic—barely,” he said. It was planned that pilots would complete training in the F-84F, to see how they would do going right out of trainers into a supersonic jet. However, they were halfway through ground school when the aircraft were grounded because of engine problems, and they were switched to the Republic F-84G Thunderjet, and went through the second half of gunnery.

Pardo’s first assignment out of gunnery school was back to the F-84F.

“They also put us in another little experiment a little bit later on,” he said. “Some of us were sent to England. The weather over there can be bad, and they wanted to see how we’d do with minimal flying time, in a single-pilot airplane.”

Those chosen for the experiment were sent to a special instrument school.

“Navigation aids weren’t very good,” he said. “We had a minimum amount of radio equipment in the airplane, and it could get kind of tough. But, everybody did fine.”

Pardo was there between 1956 and 1959, flying the F-84F before transitioning into the North American F-100 Super Sabre. At that point, the fun began; everything from the F-100 and beyond was exciting to fly. However, after flying the F-100, Pardo was unexpectedly pulled out of the cockpit.

“Not enough people were signing up to be weapon’s controllers, so they told a certain number of us that’s where we were going,” he said.

For the next three years, Pardo sat behind a radarscope.

“I got to keep flying all that time,” he said. “I’d fly target missions sometimes, which was fun.”

Through Operation Turnabout, Pardo was back in the cockpit after those three years were up. When he finished his tour in Ground Control Intercept, he went to Kansas City, Mo., to Richards-Gebaur AFB, and checked out in the Convair F-102 Delta Dagger, a fighter interceptor. With no school slot for him, he read the book on the aircraft and began flying.

“The airplane’s systems were quite similar to the F-100, so transitioning was pretty simple,” he said. “The guys in the squadron helped a lot—monkey see, monkey do. Get in the airplane, turn it on, and it either works or it doesn’t.”

After about a year and a half in the F-102, Pardo went to the Convair F-106 Delta Dart, also a fighter interceptor, which he flew in Caribou, in Northern Maine. On his way to his next assignment in Southeast Asia, in early 1966, he went to MacDill Air Force Base, Tampa, Fla., to fly the F-4 Phantom II. In the six-month school, he learned the complexities of the Air Force version of the jet, designed to do everything “fighters do,” including air superiority and close air support.

Next, it was snake (jungle survival) school in the Philippines. Pardo had been to Air Force survival school, when he was a second lieutenant, and had been through escape and evasion school, but this school taught basic survival skills for a jungle environment—skills that would later come in handy.

Following ground school, they were turned loose in the jungle for 24 hours of evasion, to be chased by natives. Each pilot carried several quarter-size small discs; he would surrender one each time he was caught.

“They could turn it in for a pound of rice, so they were interested in catching you,” Pardo said. He and two or three others managed to get home with all of their discs.

Scheduled to leave the Philippines in four or five days, Captain Pardo visited the officers club in late October 1966, and met up with a flight instructor he had in basic, who was flying out of Clark Air Base, shuttling dignitaries, classified materials, etc., from the Philippines to areas in Southeast Asia. Not wanting to wait for a transport coming through to pick up his class, Pardo hitched a ride to Bangkok, Thailand, and from there, boarded a C-130 to the North Country.

“They would land at small Special Forces camps,” he said. “They never slowed down—just continued to taxi. They’d shove stuff out the back of the airplane, go back to the end of the runway, and take off. Eventually, it made a stop in Ubon, and I got off.”

Pardo didn’t arrive at Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand, with a unit.

“We didn’t get to go as one,” he said. “Everybody went to replace someone who had either finished his tour or was MIA or killed. There was a constant turnover of people.”

Those flying over North Vietnam flew 100 missions or completed a year. Pardo explains that there was a significant difference in flying in North and South Vietnam.

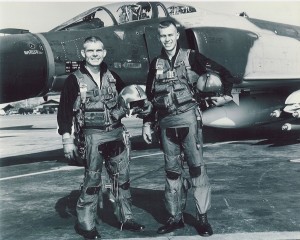

Bob Pardo followed a strong family tradition when he entered the military. “I have a very strong appreciation of what we have in this country and where it came from,” he says.

“Being stationed in Thailand, for some political reason, we weren’t allowed to dispense ordinance in South Vietnam,” he said. “In fact, we weren’t considered to even be involved in the war. We weren’t allowed to go on R&R. You’d have to take leave to get time off, but they paid us combat pay. So, we were in it, but we weren’t.”

If they wanted to make a strike in the North, they could get out to the Gulf of Tonkin, flying across South Vietnam.

“If we were going to hit the northeast railroad, that was the way to go, because you didn’t want to fly all the way across North Vietnam because of all the antiaircraft fire, missiles, MiGs and so forth,” he said. “You could get to the target and get out quicker by flying way out over the water, and coming in from the east.”

He quickly learned of the mission of the U.S. aircraft involved. The F-105s were the primary bombers; the F-4 had a dual mission.

“We would escort the F-105s, both within and outside the strike force,” he said. “We would put our dedicated MIGCAP (MiG Combat Air Patrol) airplanes outside the strike force, to roam around looking for MiGs. There were always two flights of F-4s in the strike force. We carried (iron) bombs and always carried four missiles.”

If needed, they would jettison the bombs wherever they were, to take on the MiGs and keep them off the 105s. At first they hit targets that were “hardly worthwhile.” But, at the end of February 1967, the president announced that beginning March 1, the U.S. military would start hitting big industrial targets; the first on that list was a steel mill in Thai Nguyen, the only one in North Vietnam.

“They kept it going 24 hours a day,” Pardo said.

Once the mission began to hit the mill, Pardo, dedicated to air superiority, alternated between strike CAP and MIGCAP.

“The weather really gave us fits; the first couple of days we couldn’t get there,” he said. “We ended up taking our bombs to secondary targets—either to North Vietnam or Laos, and dropping them. A couple of days, the strike force commander was able to take us directly over the target, but we couldn’t strike it because of the clouds; we couldn’t see anything.”

He added that the clouds, however, don’t bother antiaircraft shells.

“The guys up north were very good at shooting at sound,” he said. “They listened to you and figured out where they needed to be shooting. Then, the radar-guided antiaircraft guns could lock on and trap you. The clouds don’t hamper the surface-to-air missiles either; that always made it interesting.”

Pardo and others traveled the route to the steel mill for nine straight days, without being able to hit the target.

A Change In The Weather

On March 10, 1967, the weather cleared.

“We knew we were going to hit it,” Pardo said. He didn’t know, however, that over three and a half decades later, people would still be talking about what happened that day.

The participating pilots and their backseaters headed for a tanker. At the last minute, Earl Aman, a ground spare, and his backseater, 1st Lt. Robert Houghton, filled in for a crew that had to abort when their aircraft began having problems.

As was Pardo’s customary luck, he and his backseater, 1st Lt. Steve Wayne, would be flying the precarious position of tail end Charlie with the strike force.

“By the time you get there, the gunners have had a lot of practice,” Pardo said. “And, after the second day, there wasn’t any surprise. We weren’t allowed to vary the route. Someone in Washington wanted it to occur at exactly the same time every day.”

On that day, Pardo and the others were within about 50 miles of the target, when they began making a turn.

“Sure enough, the gunners open up and Earl took a hit,” Pardo said. “The airplane was flying all right. He and his backseater talked it over, and we pressed on.”

Arriving at the target, just as Pardo had pulled up to start the roll in, Aman, directly over the target, took another heavy hit from antiaircraft fire.

“He could have left right then, but he elected not to,” he said. “Down the chute we go, to get rid of our bombs.”

After nine day’s practice, says Pardo, the strike force leader was offset too far.

“He had to make kind of a circle to get back to the target, and this started jamming the people up behind him,” he said. “Everybody’s roll in was not the way it should have been. It’s like playing crack the whip; at the back end of the formation, we’re trying to follow the people in front. From the time we rolled in, we were very shallow. We were supposed to be doing a 45-degree dive, and we were doing around 15 degrees. We were way above what air speed we would normally release the bombs; we knew we needed the extra air speed to keep the bombs airborne long enough to reach something worthwhile.”

Due to their position, they were “kept down in the hot area.”

“Well, the whole place was hot,” he said. “Intelligence, the day we started, indicated about 180 antiaircraft guns within about five miles of the target. That increased daily until on the ninth day, the intelligence guy says, ‘Okay, they’ve got a thousand guns within five miles of the target. I’m not going to bother briefing this anymore.’

“At that time, they admitted to six mobile surface-to-air missile sites. The target was located within 25 or 30 miles of two MiG bases. They saw us come back day after day, and knew we were serious. They didn’t want to lose that mill. They just kept bringing in more guns; 25 percent of all the antiaircraft guns in North Vietnam ended up right there at that one target.”

Then, coming off target, Pardo took a hit.

“We had a bunch of lights on,” he said. “My backseater was cool. He says, ‘Keep flying. We’ve still got flak going off all around us.’ As we egressed, it became obvious number four (Aman) was having trouble keeping up. I started lagging back to see what his problem was.”

During radio communication, Pardo and Aman were told to use afterburners to catch up.

“The flight leader had already called for a fuel check,” he said. “We have bingo fuel, to get back to the nearest airfield. But coming off target, the ship should have had 7,000 pounds of fuel left. I only had 5,000; Earl had 2,000. When he got hit the second time, he lost a lot of fuel instantly.”

Pardo continued to fly formation with Aman, while the men approached the Red River, on the northwestern side of North Vietnam. To the west of that is the Black River, and just to the west of that, the Laotian border.

“As you’re approaching Laos, you start getting into some pretty good jungle,” said Pardo. “We were crossing the Red, climbing up, and I was trying to figure out if there was anything I could do to help Earl. It was obvious he was going to punch out; he wasn’t even going to make it out of North Vietnam. If you bail out up there, life depends on who gets you. If the civilians get you, you’re dead immediately. If the militia or the army gets you, then you have a good chance of making it to prison. Neither of those were good choices.”

Suddenly, the objective became, “What can we do to get him into the jungle over Laos?”

“The eastern half of Laos, basically, was communist-held, and the western half were still free Laotians,” Pardo said. “If the Laotian military grabbed you, that didn’t guarantee you were going to jail. From what I hear, they’d only keep you about a week, and if some North Vietnamese troops didn’t come through and buy you, they had no use for you.”

When Aman leveled off at about 30,000 feet, Pardo told him to jettison his drag chute.

“The drag chute compartment on the F-4 was the aft most thing on the airplane,” Pardo explained. “It’s a large drag chute and compartment, and I thought with the door fully open and the drag chute gone, we might be able to put the nose of the radome right in the drag chute compartment and push it. But so much turbulence was coming off the top of the airplane, that wasn’t possible.”

Instead, Pardo backed up to drop down slightly, and got in underneath Aman’s aircraft.

“I thought if we put the top of our fuselage against his belly we might be able to support him,'” he said. “Now, he had jettisoned everything else off his airplane. The only thing that he still had was the ECM pod (Electronics Counter Measures), which we used to jam the surface-to-air missiles. We didn’t want to jettison those. We wanted it to always go down on the airplane and be destroyed on impact; we didn’t want to lose that technology.”

By this time, Aman had flamed out, and was gliding. Pardo’s next idea was to get up under the belly of the aircraft.

“We’d get within about a foot of his belly, and I could feel a vacuum trying to pull us into him,” he said. “I thought, ‘That’s probably not a very good idea, because if we bump, it could jam our canopies.’ We knew we were going to punch out; we were running out of gas faster than we were burning it. We figured we had fuel leaks from the battle damage that we had taken.”

“Pardo’s Push”

Pardo backed out from under Aman. As he was sitting under the bottom of the airplane, he suddenly noticed the tail hook, which on the F-4 is large.

“The whole thing is big and strong, just like the airplane. I said, ‘That thing comes down four or five feet below the airplane, so let’s try that,'” Pardo said.

Pardo told Aman to put the hook down.

“We eased in, put the hook on our windshield and started pushing,” he said of the now famous “Pardo’s Push.” “Instead of gliding at 3,000 feet a minute vertical speed, we were able to slow down to about 1,500 feet a minute, which effectively, if you could keep it going, doubles the glide distance.”

But, they could only stay in position 20 or 30 seconds at a time.

“It swivels to the side, but once it’s down, it’s held down hydraulically,” he explained. “It does swivel, so that when you take the barrier on an aircraft carrier or on a runway, it immediately straightens the airplane out, if you’re in a crosswind or what have you.”

Staying against the windshield, which soon began to show cracks and gouges, wasn’t easy.

“I was trying to stay as far below his airplane as I could to stay out of the turbulence,” Pardo said. “I didn’t want to go any higher, but we had to, so I eased up just enough to put the hook just below the windshield on the metal. It still worked pretty good, so we continued.”

However, after about 10 minutes, Pardo’s left engine caught fire.

“We had to shut it down,” he said. “We’d go back in and try it on one engine. It didn’t work as well. The vertical speed, about the best we could do, was 2,000 feet a minute. We backed up and restarted the engine, hoping it wasn’t going to blow up. We went back in again, but within 30 to 45 seconds, it caught fire, and we shut it down again. We went about the last 10 minutes on one engine.”

Each time Pardo backed up, the other aircraft would begin sinking.

“With his engines flamed out and his hydraulics systems out, he was flying on what we call a RAT (ram air turbine), a little propeller-driven motor that generates just enough hydraulic pressure to operate the flight controls, and just enough electricity to operate one radio,” Pardo explained.

Once over the Laotian jungle and flying at about 6,000 feet, within range of “people with handguns, rifles and light machineguns,” it was time to get out from underneath Aman’s aircraft.

“We told Earl to eject, and shortly thereafter we saw both of them punch out and both chutes open, so we knew they got out of the airplane alive,” he said. “As soon as we saw the chutes, we headed for a LIMA sight, a Special Forces camp. We knew there was a little PSP (pierced steel planking) runway there. We thought we couldn’t be over 25 or 30 miles away.”

Although he knew there wasn’t enough runway to stop the aircraft, Pardo figured they could at least crash land.

“We figured that if we bellied it in, at least we’d be among friendlies,” he said. “We didn’t even get halfway there. We flamed out; we both punched. Then, the fun started.”

Pardo and the others came down about 20 miles north of Communist-held Ban Ban—”not a very good place, but at least better than going down in North Vietnam.” Wayne didn’t have any problem with his parachute ride.

“When he hit the ground, there weren’t any people around him,” Pardo said. “He just found a good hiding place and settled down to wait for the helicopter.”

When Pardo checked out his parachute, he noted that two or three panels had split slightly, but it was otherwise okay. A bigger problem was the shooting he heard on the ground as he was coming down.

“As a survival instructor, I had taught parachute techniques I learned in survival school—without ever having jumped a parachute,” he said. “So, I thought, ‘Well, this is a good time to see if all that stuff works.’ I’m having fun twisting and turning the parachute, slipping and sliding. About that time, I hear this explosion, and I have a hell of a pain in my hip.”

At a certain altitude, he explained, the life raft is supposed to inflate.

“The survival kit in the pack is supposed to fall away from you,” he said. “It didn’t. The pack didn’t come undone so the survival kit could drop away. The life raft said, ‘Too bad; I’m supposed to be inflated, so I’m inflating.’ A little balloon had come out; it just couldn’t take any more pressure and exploded. When it did, the rubber slapped me on the leg and scared the hell out of me.”

Pardo surveyed the landing areas and decided they weren’t the best. Looking down the mountain, he saw a small open spot, and decided to see if he could slip forward to it.

“I hit a dead tree,” he said. “It was so dead that it wouldn’t grab the chute enough to stop me. I’m breaking branches and limbs as I’m going through. It collapsed the canopy. Now, I’m just freefalling. I landed in some rocks. When my feet hit, my butt hit and my chin hit right in between my feet.”

Pardo was slightly conscious for a couple of minutes, before slipping into unconsciousness.

“I found out later that I’d broken two vertebrae in my neck,” he said. “When I woke up, I could hear people further down the mountain shooting and hollering, heading my way.”

Pardo struggled, but couldn’t get his canopy out of the tree.

“A canopy is always good to have in a survival situation, but I couldn’t wait for that, so I got the survival kit out of the pack and started boogying up hill,” he said. “I climbed about 3,000 feet of mountain in about five minutes.”

When he got to the ridgeline, he found what he first considered a good hiding place—a big hole full of leaves, behind a huge tree. He began digging the leaves out, so he could get in and pull them back over him, when he remembered something: Cobras!

Stuck Between a Medal and a Court Martial (part 2)