By Di Freeze

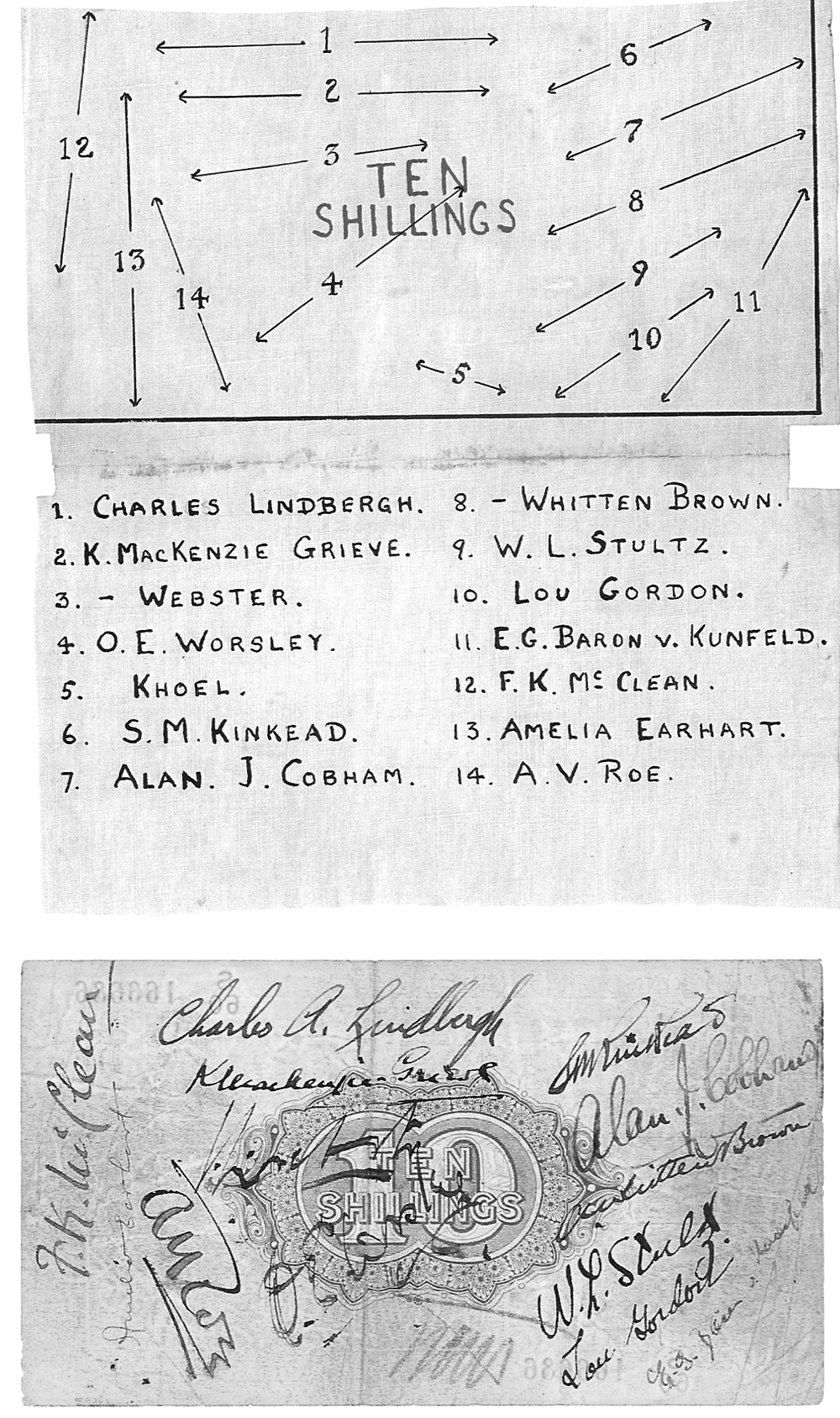

The pride of Chuck Holmes’ autograph collection is this 10-shilling note, which bears the signatures of 14 famous over-water flyers, including Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart.

The Colorado Aviation History Society began its work in 1966 to honor the state’s aviation pioneers, and those at the time furthering the industry. They continue to do so; helping in this endeavor to preserve history is Charles W. “Chuck” Holmes.

Holmes began his work with the society over two decades ago, in 1982, and has been a board member since 1983. In 1994, the Greeley resident, who had undertaken an unfinished project, completed “The Honoree Album of the Colorado Aviation Hall of Fame,” whose first members, honored in 1969, included balloonist Ivy Baldwin (see page 29).

Since then, Holmes has devoted much of his time to collecting biographies and corresponding photographs for the three-ring binder, distributed to members of the society, public libraries and others, and supplying new pages each year, as the list of inductees grows.

His work with the society doesn’t stop at editing that album. When the directors started on the major project of the Heritage Room at the Wings Over the Rockies Museum, Holmes volunteered to prepare all of the plaques for the honorees, Holmes wrote most of them, and prepared the pictures and mounted them for presentation.

It’s fitting that the man who has spent years honoring others for their accomplishments has in recent years been honored for his. The CAHS honored Holmes with a Special Recognition Award in 2001. An active member of the Antique Airplane Association of the Aviation Internationale (Estes Park) and other aviation organizations, Holmes is also a board member of the OX5 Pioneers, which honored him in 2002 as Aviation Historian of the Year, citing his “unselfish efforts” and demonstration of rare qualities “towards the preservation of the true aviation spirit.”

Born in 1925, Holmes was educated in Gardner, Mass., and after graduation from high school, entered the Army Air Forces, as an aviation cadet. He went to Buckley Air Field for basic training, but was a victim of a huge epidemic of rheumatic fever, which grounded him permanently.

Shortly thereafter, he was assigned to gunnery school, at Laredo, Texas, from which he graduated as an aerial gunner on B-24 bombers. Later, after crew training, he was reassigned to parachute rigging and repair.

After the war, Holmes returned to Colorado, where he entered Colorado State College of Education (now UNC), from which he graduated with courses in science and mathematics, and later earned a master’s in audiovisual administration.

He later joined the Greeley Public Schools, teaching in junior high schools before becoming the district coordinator of audiovisual and libraries. He also taught classes for Colorado University and UNC, before retiring in 1988. A reward for introducing aviation into the science curriculum whenever possible was hearing later that some students had become military and airline pilots.

Like another well-known Holmes, the historian has spent countless hours sleuthing for obscure information, and in so doing, has met many of the world’s aviators, famed and not so well known, as well as becoming a resource for others who have been able to glean knowledge from his large personal library of books and videotapes—and from his contacts with other aviation historians.

Among his treasures is a collection of autographs that includes 116 of the 178 members of the Colorado Aviation Hall of Fame, but is far from being limited to those signatures. Holmes began his autograph collection in 1972, when he decided he wanted Igor Sikorsky to autograph a book the aircraft designer had written. Holmes wrote a letter with his request, and sent the book to the author. It soon came back with the coveted signature. That was enough to convince Holmes to try for other signatures. He now has a prized collection of over 450 books signed by the author and/or subject. However, he has over three times that number in signatures.

Holmes said it isn’t as easy as just sending the book off. The secret to his successful “autograph collection” has been writing a letter that establishes a common thread, and, he says, never actually using the words “autograph” or “collection.” He adds that sending a return envelope, complete with proper postage, is important.

One of his books contains the signatures of James “Jimmy” H. Doolittle and 18 members of the Tokyo Raiders, as well as that of the book’s author. Holmes, who delights in sharing his knowledge with others, recently sent a letter to the “Journal,” which was accompanied by a photograph of a 10-shilling note. The pride of his autograph collection, the note bears the signatures of 14 famous over-water flyers, signed, he believes, in an 18-month period during 1927-28.

Holmes said he heard about the historical piece in 1983, while his wife attended a nursing school reunion, and he killed time in Omaha, Neb.

“I stopped in at a used book store, which was reputed to be an antiquarian book shop, and when I asked about their having any autographed books in stock, I was told by the owner that he had one item in his home in which I might be interested,” Holmes said.

That person’s mother, who lived in England, had purchased the item from the Phillips Auction House in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1977.

“After writing to him later, I found that two of the names on this paper money were Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart,” Holmes said. “I just had to have it.”

Holmes was promised provenience on its authenticity, but it never came, even after continued requests.

“But I have no question in my mind about its being genuine,” he said.

At the time that the note was signed, Holmes said, it was common for large testimonial banquets to be held to honor someone who broke a flying record.

The Colorado Aviation Historical Society presented Chuck Holmes with a Special Recognition Award in 2001. Holmes, second from left, is shown with (L to R) Gordon Page (at the time president of the CAHS), Robert C. Cherry (2001 inductee, now deceased), Lt.

“It seems that everyone who had a plane, and perhaps a license, searched for a record to break, and many of these were done,” he said. “Some of these banquets were really posh and only those persons well connected might gain entry. I believe that this note was signed for some person with the connections to have been invited to attend.

Holmes adds that he knows that the note wasn’t signed at one place and time.

“A time line of the personal dates of the signers with the dates of their accomplishments and deaths proves that fact,” he said. “This note was carried from place to place in a wallet or purse and shows some wear on it.”

The note was issued first in October 1919, but is not dated.

“It fits with the years in question,” he said.

Those who signed the note are Lindbergh, Earhart, Arthur Whitten Brown, Alan J. Cobham, Lou Gordon, Wilmer Stultz, Kenneth McKenzie Grieve, Hermann Koehl, E.G. Baron Von Huenefeld, Francis K. McClean, Alliot Verdon Rose, Sydney N. Webster, C.E. Worsley and Sam Kinkead.

Holmes said the original owner had the forethought to make a “map” of the side of the note holding the signatures, done on a piece of light blue oilskin paper and indicating, through arrows, where each name is placed.

“Without this help, some of the signatures would be unrecognizable today,” Holmes said. “To preserve this information, the map was placed behind the note in a frame, which is how I received it.”

Holmes gave a brief history of the signers.

“Lou Gordon and Wilmer Stultz were the crew of the Fokker airplane, ‘Friendship,’ in which Amelia Earhart flew the Atlantic (as a passenger) in June of 1928,” he said.

Stultz died in a crash on July 1, 1929.

“He had alcohol problems and took two passengers with him when he died,” he said. “Lou Gordon lived for many more years.”

Baron Guenther Von Huenefeld and Capt. Hermann Koehl, both German World War I combat veterans, with a third crewmember, Maj. James Fitzmaurice, an Irish military pilot, had the distinction of flying the first plane, a Junkers W-33, across the Atlantic from east to west. At that time, Koehl was on leave from his piloting job at Lufthansa. Von Huenefeld promoted the flight.

“Their plane can be seen today in the Ford Museum, in Dearborn, Michigan,” said Holmes.

Kenneth McKenzie Grieve attempted an Atlantic crossing with Harry Hawker, in the “Atlantic,” in May 1919. The “Daily Mail” sponsored the flight with a 10,000-pound prize.

“They landed on the sea about halfway across,” said Holmes. “They were rescued by a fishing boat, which had no radio, and for about a week were presumed dead.” When they returned, the sponsor, happy that they had survived, awarded them with half of the prize money.

“The eventual winner of the trip still received the full prize,” Holmes said. “McKenzie Grieve later made many other important flights.”

Alan Cobham, a famous long-distance flyer in England who had owned an air circus, flew from England to Australia and back in 1919, in a DH-50 biplane.

“He proposed and experimented with mid-air refueling through hoses, and also flew from England to the Cape of Good Hope and back in 1925,” said Holmes. “On a flight to Australia, with a mechanic and a motion picture cameraman, his mechanic was shot to death from the ground while flying over Baghdad. Cobham also pioneered many of the early air routes flown by Imperial Airways and lived to a ripe old age, dying in October 1973.”

Arthur Whitten Brown was the mechanic and copilot on the John Alcock Vickers Vimy bomber, which flew the Atlantic on June 14, 1919.

“Although this trip was hazardous, it proved to be successful,” said Holmes.

“Alcock died in a crash of the same type of plane in December of that same year in France. Brown never flew again, and died in 1948. The plane is now in the Science Museum in South Kensington, London, England. Both men were knighted for their success on the flight.”

Francis “Frank” McClean owned a Short-built Wright plane in the very early years of aviation, and in August 1912, flew a Short floatplane under all the bridges on the Thames, including the Tower Bridge in London, and landed on the river at Westminster.

“He was reprimanded by the police for both acts but adored by the public,” said Holmes. “He was forced to taxi back down the river to his starting place.”

Sydney N. Webster was the winner of the (all seaplane) 1927 Schneider Cup race, held in Venice, Italy.

“The major countries flying in this prestigious biannual race were the United States, England, France and Italy,” Holmes said. “Many great records were made with these planes, which included the Supermarine racers, which were designed by R.J. Mitchell, who later designed the famous Spitfire, which made its name in the Battle of Britain.

“O.E. Worsley came in second in another Supermarine S-5. Sam Kinkead, a WWI ace born in South Africa, also flew, but failed to finish because of a malfunctioning reduction gear in the propeller mechanism of his Gloster IV biplane. He still holds the speed record for biplanes at 277.1 mph. He was killed while practicing for the next year’s race. Jimmy Doolittle of the United States team won the race in 1925, and David Rittenhouse won for the USA with a Curtiss racer in 1923. The British retired the cup in 1931.”

The final name on the note is Sir (Edwin) Alliot Verdon Roe (1877-1958) who was, says Holmes, possibly the first person to fly a heavier-than-air craft in England, but was declared the second.

“He did build and flew the first HTA craft, which he called his Avroplane,” said Holmes. “He was a pioneer aircraft designer and builder who built the AVRO planes, which were very famous up to World War II.”

Holmes believes the note may have been signed at the International Civil Aviation Conference, held in 1928, and the Air League of the British Empire Conference, held in London in 1928. One reason for his belief the note “traveled” is that at least one signer died before others did their “thing.”

He admits that it is pure conjecture on his part that the person who carried the note, and had it signed by these 14 important people, was one of several women who had influence, money and position, and made major contributions to public life and government. Possibilities, he said, are Lady

Mary Heath, a wealthy pilot of some note; Lady Houston, the widow of a millionaire magnate who gave 100,000 pounds to the British government to finance the Schneider entry one year when the government couldn’t raise the money; and Mrs. Amy Phipps Guest, owner of the “Friendship” aircraft and a sponsor of the Earhart flight.

“She was also the wife of the former British air minister and heiress to a steel fortune,” Holmes said. “Pictures show her in a boat greeting Amelia Earhart on her arrival in Burry Port, Wales.”

Another is Mrs. Foster Welsh, the first woman lord mayor of Southampton, England. Holmes said that in his correspondence with the Phillips Auction House, they were unable to verify that the note was ever sold there, because it was, in all probability, sold as part of a lot.

Holmes says that signatures of Lindbergh are fairly common, because he lived so long (1902-1974), although he was reluctant to sign items in his later years.

“Signings of Amelia Earhart (1897-1937) are much rarer, because she lived so short a life after her aviation exploits,” he said. “The same can be said of some others who signed the note. I personally have never heard of another item, which had been signed by both Earhart and Lindbergh at the same time, if ever.”

Holmes said that he had hoped a write-up in “FlyPast” magazine, published in England in 1985, would elicit some response from readers, but that he received no inquiries or further information.

He hesitates to say what he believes the true value of the relic is today, but adds that he would never sell it. Holmes does have plans for that and other memorabilia, however. He will eventually divide his bounty between the Wings

Over the Rockies Museum and the CAHS. The nonprofit society’s inheritance will include his signed aviation books.

Holmes has set one firm rule for himself, when it comes to the information he provides to others. He doesn’t sell anything.

“I never have and I never will,” he said.