By James G. Stanley

After a brief slow-down in a long and illustrious aviation career, Robert E. Drew moved his family and commercial real estate consulting business from southern California to Seattle, in 1990.

Later, he teamed with The Museum of Flight as a volunteer docent and youth education instructor. He is now deeply involved in research of World War II fighter planes for a new display wing at the museum.

Drew’s experiences as a Douglas test pilot are legendary, including that with the Douglas F4D “Skyray.”

Douglas F4D “Skyray”

The tailless, bat-winged Douglas F4D “Skyray” nosed over at 50,000 feet in an 80-degree power dive on the way to a pullout maneuver at altitude not to exceed 7,500 feet.

This structural and aerodynamic test, called Positive Low Angle of Attack Pullout, was a standard Navy specification, SR-38, performance criterion for new fighter aircraft. All systems were “go” during the rapid climb to altitude; the test pilot confidently entered a combination push over/wing over technique at zero gravity into an increasing wind gradient, as the nose turned steeply downward.

This test, in early 1956, was conducted over the open ocean to assure adequate altitude for recovery and to move shock waves away from populated areas. It was routine until test pilot Bob Drew realized that on initiation of pullout at 30,000 feet, at full aft-stick and speed of Mach 1.55, the rate of dive angle decrease was much slower than his earlier similar test flight. The present maneuver generated only 1.5 G’s, as opposed to 2.3 G’s on the previous flight. This was unexpected, since the pitch-trimmer setting had been reduced only one degree from the last flight, where level flight was attained at 3,500 feet. Wind tunnel tests had not indicated this potential decrease in control effectiveness. Since the rate of descent of the F4D at this time was 60,000 feet per minute (the altimeter needle was spinning), Drew had to make a split-second decision.

He decided to try to complete the test!

Slowly, the G-factor increased and the nose came up as the test continued at full power and indicated airspeed of 770 mph. Upon achieving the PLAA test point, 7,500 feet altitude, it was time to complete the pullout or end up in the drink.

Bob Drew, in the mid-fifties, serving as the project engineering test pilot on the F4D Skyray, the F5D Skylancer and the AFC Skyhawk.

Chopping the power, while maintaining full aft-stick and attempting to add up trim, began immediate full recovery. It wasn’t until the F4D slowed to subsonic speed, however, at approximately 6,000 feet altitude, before adequate control effectiveness and pitch-up angle response was obtained.

The last few seconds of dive recovery was hectic, to say the least, as level flight was achieved right on the deck and just before impact with the water.

Drew reported that it felt as though ocean spray was coming over the cockpit. He had a crazy thought: “Maybe if the aircraft hits the surface flat enough, it will bounce up and give me time to eject?”

Meanwhile, as speed fell, the Skyray finally responded to the stick-back, plus up trim at level out, and almost immediately was in a near-vertical climb, pitching up at nearly 7 G’s. Drew quickly pushed the stick full-forward, applied full power, and moved the trim back to faired position. The fighter responded, stayed in one piece, and leveled off at 4,000 feet altitude.

Drew’s chase pilot’s voice came over the radio: “I thought you were going in that time.”

“So did I,” said Drew.

The test chase pilot, Captain Mel Apt, USAF, in a F-100 Super Sabre, pulled up in close formation to look over the Skyray on the return to Edwards Air Force Base. He reported some wrinkled skin and popped rivets. In that condition, Drew made a straight-in approach to base andlanded without incident.

The Edwards test pilots staged a wild “Welcome Back” party that night, and the day was made complete by the approval of the flight data reduction and the desired final PLAA point being achieved.

Robert E. Drew

Drew was born in southern California, and like many other draft-age Americans during the early days of World War II, decided he preferred to fly rather than spend the next few years in the infantry or at sea. He enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1943, and earned his commission and silver wings at Williams Air Force Base, Arizona. Beginning on May 13, 1943, he graduated in 13 months plus 13 days. He completed transition training and was assigned to the 13th Air Force in the South Pacific.

After 13 months overseas, he returned to the United States. One of his sons was born on Friday the 13th in October; good

thing he had never been superstitious!

Drew’s assignment in the South Pacific Theater in 1945 was as a fighter pilot in P-38 Lightning and P-51 Mustang aircraft. He became a flight commander and squadron operations officer by the time he was discharged in 1946.

Drew joined the California National Guard in 1946 as a flight commander, and during his CNG service joined the Douglas Aircraft Company as flight test engineer, in 1952. His work on various test programs led to transitioning to production test pilot status at Douglas Aircraft on the Navy AD Skyraiders, and later to engineering flight test on the F4D Skyray at Edwards AFB.

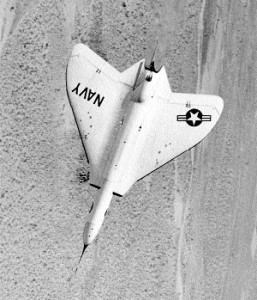

The Douglas F4D Skyray was no doubt named for its resemblance from above or below to a giant manta ray. It was designed during the Cold War as a high-altitude interceptor for defense of the U.S. fleet against possible Soviet air attack. The XF4D-1 prototype first flew on Jan. 23, 1951; only 419 were built during its service life from 1956 to 1962. It was primarily known for its fantastic climb rate, providing outstanding capability to scramble against high-flying bombers. This airplane holds the unofficial world record from brakes-off to 10,000 feet altitude, at 56 seconds.

The F4D was also the first delta-wing aircraft to attain supersonic flight and it held the world speed record for both three-kilometer and 100-kilometer courses, as well as five Time-To-Climb records in the early 1950s. It was the first Navy airplane to hold world speed records since a Navy seaplane set the record in 1934.

For his design and development of the record-setting Skyray, long-time chief engineer at Douglas Aircraft, Ed Heinemann, was awarded the Collier Trophy.

Bob Drew served as the project test pilot for the Skyray and, after the preliminary tests at Edwards, completed the formal structural and aerodynamic demonstration tests required at the Naval Air Test Center at Patuxent River, Maryland, in 1956. Some of his chase pilots at both NATC and Edwards were future astronauts Deke Slayton and Al Shepard, pilots Ivan Kincheloe and Mel Apt of the altitude and speed record holder X-2, and Captains Bob White and Bob Rushworth, pilots of the hypersonic X-15.

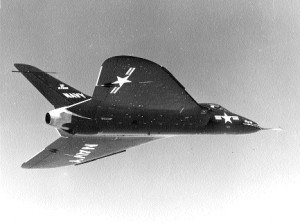

The F4D was a challenging and thrilling airplane to fly. Later models were powered by a Pratt and Whitney J-57-P8A, twin-spool, axial flow turbojet with afterburner, which runs cool under all conditions and has excellent starting characteristics on the ground and in the air. The engine may be handled rather abruptly in the traffic pattern if emergencies arise, though not recommended in normal circumstances. The aircraft has hydraulically-actuated controls with a built-in artificial “feel” system. The control surfaces are elevons (combination elevators and ailerons), which are actuated symmetrically for pitch control and asymmetrically for roll. A mechanical disconnect can be operated by the pilot in the event of failure of both 3,000-pound irreversible power supplies.

The Skyray was one of the most advanced interceptors of its era, and Navy and Marine pilots who flew it praise this jet as a little-appreciated legend. Nonetheless, its service life was short, due to a number of technical problems with early models and rapid technological advances during the Cold War.

Drew continued flight test work for Douglas Aircraft until 1962, flying everything from subsonic and supersonic fighters to four-engine, commercial airliners and military cargo craft. He also flight tested and competed in Formula One Pylon Racers across the country for 40 years, between 1953 and 1993.

In total, this combat, test and racing pilot accumulated nearly 10,000 hours of flight time in more than 75 aircraft types over the past 50 years. Very few could match his amazing aviation record!

Robert Drew’s wife was formerly a TWA Stewardess, and one of his three sons races Formula Mazda sport cars nationally; Drew is his crew chief.