|

By AJ Staff

Entrepreneur Greg Herrick says the Golden Age of Aviation has been forgotten. Because of that belief, he’s formed the Aviation Foundation of America, a nonprofit organization for which he serves as CEO and president dedicated to making sure that others remember that era. “Everyone remembers that on Dec. 17, 1903, at Kitty Hawk, N.C., the Wright brothers made the world’s first powered flight,” Herrick said. “Then, for some reason, people seem to think that the history of general aviation went from there to barnstorming to the jet age. Back up; that’s wrong! If it hadn’t been for the Golden Age, we wouldn’t have had the jet age of flight.” The Golden Age was carved out between 1925 and 1931. “In the U.S., many advancements in aviation occurred during World War I and World War II—a time that became the Golden Age,” Herrick explained. “Ironically, that time has been overshadowed by the aircraft and action of the two wars that framed it.” Herrick, who personally owns more than 35 vintage aircraft, one of the largest holdings of aircraft in the U.S., admits he’s invested $10 million or more into purchasing and restoring them. He says he knows people often ask this question: “Why would a man who made a substantial amount of money in the nineties from the sale of his mail-order computer business (Zeos International) chase aircraft around the world—and to his detriment at times—give a damn about the Golden Age?” Herrick, who earned his private pilot’s license as a high school graduation present from his parents, says he’s the only one in his family to become a pilot, so he didn’t inherit his passion. His unexplainable love for vintage aircraft started early, when he grew up in Ottumwa, Iowa, where headquarters for the Antique Airplane Association was located. |

“I remember in grade school they’d have fly-ins where old airplanes would come in from all parts of the world,” Herrick said. “I never forgot that, so when I found that I was in a financial position to give back, I wanted people to remember the Golden Age.”

Spectators stand on their tiptoes to get a glimpse of this 1927 Ford 4-AT Tri-Motor, during the original Ford Air Tours.

Fifteen years ago, after not flying for decades, Herrick purchased his first vintage aircraft, a 1943 Fairchild PT-23, and brushed up on his flying skills. Although that particular plane wasn’t part of the Golden Age, it’s what pushed him more in that direction because he thought there were enough warbirds.

“Frankly, the world doesn’t really need another restored P-51,” he laughs.

Most of Herrick’s vintage jewels are stored at the Anoka County-Blaine Airport, near Minneapolis, where he opened the Golden Wings Flying Museum.

“You can’t just walk in, but for those who lust after vintage birds, we’ll open the doors,” he said, adding that numerous pilots have had marriage ceremonies performed at his museum over the years.

Herrick agrees that he’s been lucky to have had the money and time to fiddle around with vintage aircraft. However, he wasn’t satisfied with that, so he created an event he could share with the world, the National Air Tour 2003.

Greg Herrick and Edsel Ford II are never too busy to talk about airplanes; Ford waved the flag to start the National Air Tour 2003—something his grandfather did more than 72 years ago.

The National Air Tour 2003

Herrick recently accomplished something that hadn’t been done since 1931; he recreated the Commercial Airplane Reliability Tours, which became known as the Ford Air Tours.

During the tours, winners who completed the tours with “reliability,” those that flew safely and didn’t hotdog or perform daredevil antics, received the “Edsel B. Ford Trophy.”

During the mid-1920s, Henry Ford and his only son Edsel wanted to prove that flying was safe, so they sponsored the tours. However, in 1932, the scheduled annual tour was cancelled because people were still feeling the sting from the Great Depression, and there wasn’t enough money to welcome touring pilots.

“The annual tour not only promoted aviation, but also encouraged cities and towns to build airports or improve the existing ones they had, which were mostly muddy fields posing as airstrips,” Herrick said. “The Ford tours promoted aviation advancements in both aircraft technology and aviation infrastructure.

Most people don’t know this, but Henry Ford was the first person to build a concrete runway. Dozens of aircraft featuring the latest in aircraft development toured across the U.S., which created a traveling air show of sorts.”

The FAA’s DC-3 was flown by FAA pilots and crew Michael F. Ahern, John H. Boatright, Kim Brown (honoring Earl K. Campbell), Richard Delafield, Thomas H. Dorman, Stanley T. Cole, Jorge A. Malcun, JC Pierce Jr. (honoring Ernest Greenwood) & Scott Thompson.

On Sept. 8, 2003, at the start of the recent National Air Tour, Edsel B. Ford II waved the starting flag—the same dedication that his grandfather, Edsel B. Ford, had done 72 years ago to promote the tours. At the close of another historical chapter in history, more than 80 volunteer pilots and crew from 20 states and Canada returned to Willow Run Airport, Ypsilanti, Mich., and completed the 4,000-mile journey that was cancelled all those years ago.

“For more than two weeks, pilots flew rare birds from the twenties and thirties over America’s great landscapes,” said Herrick. “For myself and for all the wonderful pilots, we’re happy that we could share a unique slice of aviation history with hundreds of thousands of people.”

Every Plane Tells A Story

Herrick laughs and says he knows he’s become a “fanatic” at collecting, but he can’t stop now.

“Currently, I’m restoring other aircraft in New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Georgia, Iowa and Michigan,” he said. “For example, exclusive of the cost of restoration, a vintage J-3 Cub costs about $25,000—well over 10 times its original cost.”

Gene Frank, a former crop-duster, sold Greg Herrick this 1938 Cunningham-Hall PT-6F and his 4-AT Ford Tri-Motor.

Herrick does his best to restore the aircraft to the color it originally was at the time it rolled out of the factory.

“If I don’t know what color it was originally, I’ll try to find out what color it was when it performed a certain kind of service,” he said. “In the case of my Stinson Tri-Motor, the oldest surviving American Airlines airplane, which flew over a million and a half miles carrying over 100,000 passengers, I chose American’s paint scheme even though it flew for four other airliners.”

Herrick said paintjobs run a range of $2,000 to $25,000, depending on the airplane. Wingspan length and other factors, such as having to sand down the entire frame, drive the price. For example, his 1927 Ford Tri-Motor, which is almost ready for flight, cost about $20,000 to paint.

One of Herrick’s missions is to show people that vintage aircraft aren’t going to “fall out of the sky.”

“These restored aircraft, mine and others, are gone over with a fine toothed comb; they’re in better condition than a used Boeing 747,” he said.

Finding vintage aircraft is what sometimes poses a problem. In fact, it can be downright dangerous, but Herrick stops at nothing to obtain them. For instance, one time he ignored a “No Trespassing” sign on Gene Frank’s ranch in Caldwell, Idaho, and was confronted by the rancher’s dog, which jumped up against his car door. Thinking quickly, Herrick tossed the dog a cracker with peanut butter on it, hoping he could get close enough to the oldest Ford 4-AT Tri-Motor in existence.

“I got out of my car real slowly and told the dog to sit,” he said. “When the dog sat, I gave him more crackers. I was all set.”

Herrick had spent several years calling the rancher, but this time he meant to convince him once and for all to sell the plane, which was lying in poor state behind a wire fence. However, when Frank drove up in his pickup and saw that his guard dog wasn’t minding the store, he reached for his shotgun.

“That damn dog!” Herrick recalled the rancher saying. “I told him I’d won the dog over with crackers, so he didn’t shoot him.”

They became friends, and Frank eventually did sell the Tri-Motor to Herrick. He also sold him several other vintage beauties he had, such as a 1938 Cunningham-Hall PT-6F and a 1929 Keystone-Loening Commuter K-84, which is the last biplane flying boat of its type.

Grover Loening designed the first flying boat while he worked for the Wright brothers. After opening his own company, he competed for Navy contracts with Leroy Grumman, who was then one of his employees. Before Frank acquired the K-4 in 1954, it was under the control of Alaskan Airlines.

“Even though we’re good buddies, he was teary-eyed when he sold his planes to me,” Herrick said. “You have to understand the mindset of pilots who have these vintage aircraft. Like Gene, who was a crop-duster pilot, they see tremendous personal value in them, which you have to respect.”

For Frank and other pilots who’ve sold their prized possessions of history to Herrick, seeing them completely restored to the luster they originally had is also emotional, but they’re grateful at the same time.

“This particular Ford Tri-Motor is special,” says Herrick. “The tail number, NC-1077, is the very aircraft that was flown by Harry Brooks, who was Henry Ford’s chief pilot. This was also the very airplane that transported Evangeline Land Lindbergh to Mexico City, where she’d visited her son Charles Lindbergh, who also flew this plane.”

Herrick said that to keep the plane’s integrity, he won’t paint it.

“The word Ford is painted on the side over its natural skin of aluminum,” he explains. “The people working on its restoration pulled it outside of the hangar, but because it’s so shiny, they could hardly work on it.”

Herrick said that vintage aircraft strikes a pang in the hearts of thousands of people who in yesteryear watched them fly overhead.

“It was a time when children would run out to meet a pilot, run their hands along the airframe, step inside and gawk at the cockpit controls—as if they had just landed on the moon or something,” he said. “Today, nobody runs out to see a modern aircraft. Today, nobody cares if we go to the moon.”

However, said Herrick, fly a 1931 Sikorsky S-39-C painted like a giraffe, like the one Dick Jackson owns, or the 1929 Sikorsky S-38 with the zebra paint scheme Thomas Schrade owns—both of which flew in the 2003 tour—and people will notice that. Herrick explained that the reason for the paintjob on the original flying boat came about so the natives wouldn’t become frightened when exploratory flights took place in Africa.

He added that the first flight was Dec. 24, 1929, but on Dec. 30, the aircraft crashed due to lack of power from one engine. However, the little short-hulled float-boat established an envious service record when the S-39 Sprit of Africa, flown by Osa and Martin Johnson, established two aviation world records.

Herrick has hopes of restoring a 1931 Sikorsky S-39 one day, but first he has to rescue it from the bottom of a lakebed, where it sunk in 1958, into glacial silt—about the consistency of peanut butter. He’s spent about $200,000 in rescue operations.

This beautiful 1929 Alliance Argo, owned by Greg Herrick, is displayed at his Golden Wings Museum. Built by Alliance Aircraft, only two of this type of aircraft remain today; Herrick’s is the only one that’s airworthy.

His obsession in obtaining this rare craft started as most of his hunts do; he looks them up in the late Joe Juptner’s nine-volume U.S. Civil Aircraft series.

“Then, I comb the Federal Aviation Administration’s register to see how many of a certain type are still in existence,” Herrick says.

In 1996, he located three Sikorsky S-39s—one not salvageable, one in a museum and one whose owner didn’t return Herrick’s phone calls over a six-month period. Pilot Victor Lenhart was the owner; Herrick tracked him down after he had called every Lenhart listed in a nationwide Internet phonebook.

“When he returned my call, he said, ‘You’ll have to bring it up from Two Lakes in Alaska; it hasn’t been touched since,'” Herrick recalled.

Lenhart didn’t want to return to the crash site, where he and his wife lost most of their possessions and their lifelong dream of starting a hunting lodge at Two Lakes, but Herrick’s boyish charm, and a little “pleading” convinced Lenhart to help him.

The two men stood looking over the lakebed with Lenhart pointing to where he thought it had sunk, but Herrick’s sonar device couldn’t locate it. Later, a park survey map identified the distance of the crash from different points on shore, which finally led to the discovery of the S-39. Herrick was initially ecstatic.

“It was good news at first,” he said. “The bad news was that the attempt to lift the Sikorsky failed after lines hooked to the plane snapped. As boats tried pulling it up to the surface, it was dead weight sitting 213 feet below on a bed of mud. All of us stood there and cried like babies.”

After that rescue stint failed, Herrick brought a fully equipped team of professional scuba divers in, which would have to clean debris from the aircraft, sitting on the bottom of the lakebed. Because the divers had to dive down to such deep levels, they sat in a decompression chamber after they resurfaced to avoid getting the bends. That was two years ago.

Owned by Greg Herrick and on display at the Golden Wings Museum, this eye-catching 1929 Buhl Sport Airsedan is in perfect condition after restoration.

“The last effort didn’t lead to much progress, so my team has gone back to the drawing board to figure out another approach,” he said. “When I do find a way to successfully rescue my Sikorsky, I’m going to paint the wings silver and the fuselage a yellow color that was of its time.”

Herrick says that if you’re going to become a professional aircraft connoisseur, disappointments are to be expected.

“Right now I’m looking for wreckage somewhere in South America—a Curtiss Condor is there somewhere, but that’s all I know,” he says. “I found out about it from investigating accident records, but I don’t know what I’m going to find.”

What Herrick does is similar to that of archeologists; he spends a lot of money recruiting “find crews.” Carefully, but in a timely fashion, he has to determine an exact location, which is a daunting undertaking—one that requires nerves of steel and the patience of a saint.

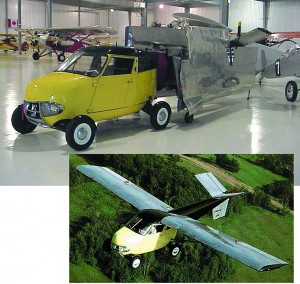

Herrick said that although many rescued aircraft involve expensive machinery efforts, there have been times when animals have been used to help pull aircraft out of hard to reach places, such as the depths of canyons. As dangerous as it can be at times, there are finds that bring a humor of sorts to the situation, such as the comedy of his 1954 Aero Car.

“The Aero Car was used for many years doing traffic reports in Seattle,” he said. “It had about 700 hours on it when I purchased it. Molt Taylor, the plane/car designer, had always said, ‘Sooner or later cars would fly.'”

The Aero Car, with detachable wings, converts from road car to plane in 10 minutes.

“Of the five craft made, I’m flying one that’s airworthy, but on the whole, they weren’t great cars or planes,” he said.

A glorious moment in Herrick’s life was finding out about the history of his Stinson Tri-Motor.

“In March 2001, this old American airplane turned 70 years old,” he smiles. “Before people flew in it, horses, mail and all sorts of freight and parcels made destinations via this aircraft.”

At one point, the aircraft was used as a crop duster and on another occasion, it flew as a bush plane. However, Herrick pointed out that there’s another interesting fact about this particular plane; it was National’s first Tri-Motor for a brief time in 1937. More research revealed that on National’s first flight, Charlotte “Georgie” Robbins, the airline’s first stewardess, went through an experience that led to the discovery that the plane had engine problems and had to crash-land.

Since Robbins was new to her job, she wasn’t familiar with the sounds of the aircraft, and when passengers became nervous because they heard strange sounds from the engine, she tried to calm them down by saying, “The pilots have to adjust the stabilizer every time I walk up and down the aisle; it’s all perfectly normal.”

“That wasn’t normal at all,” Herrick said. “From detailed accounts we know that they made a stop at Miami, and then continued on to St. Petersburg, where during the flight she was called to the cockpit and informed they were about to make an emergency landing because of an engine problem.”

Robbins strapped herself tight into her jump seat and waited until the plane landed harmlessly in a farmer’s muddy field. The only real mishap was to Robbins’ uniform, designed and made by the stewardess and her mother, which was muddied when she waded out of the swamp. Her one magnificent year as a stewardess ended, too, when her boss explained that the added frill of having a stewardess was an expense he no longer could afford.

Herrick said that finding old one-of-a-kind Golden Age aircraft sometimes brings with it “mixed emotion.” Such was the case of his 1927 Avro Avian 7083, the same type of plane Amelia Earhart was flying when she disappeared.

“To resurrect, if you will, Amelia’s Avian 7083, it was necessary to travel to Australia, which is where I located a sister ship that had been manufactured only a few weeks earlier, back in 1927,” Herrick explains. “I acquired it in 2001; by the time it left Australia, it was the oldest registered flying airplane in the country. The Avian was destined to recreate Amelia’s first record flight.”

However, that wouldn’t be its first significant flight re-creation. Its former owner, Lang Kidby, took on what even today would be a daring adventure.

“In 1998, Kidby duplicated Bert Hinkler’s incredible 11,000-mile flight of seven decades earlier, from England to Australia,” Herrick said.

When Herrick got the news that the plane was available, he contacted Kidby who pointed out the illustrious history of Avians and their penchant for being involved in record-setting flights by historically important pilots.

“Being an admirer of Amelia, I was reminded of her flight in the Avro Avian 7083, and the idea struck me—why not honor her by duplicating her 1928 fight?” he said.

Another record-setting aircraft of the Golden Age is Herrick’s eye-catching 1928 Stinson Detroiter SM-1B.

“Like so many of the aircraft of its time, this one has a unique story, as it was considered a refined plane of its day with an enclosed cabin and wheel brakes, and was a self-starter,” says Herrick. “It had a Wright radial engine and made headlines with a near 13,000-mile flight from the U.S. across the Atlantic to Japan. It was a hazardous flight. When it reached two-thirds of the way around the world, the flight ended in Tokyo. The airplane was shipped home to the relief of the pilots, who then realized the folly of their undertaking.”

A Detroiter also made the first flight from New York to the Bahamas, which was also a dangerous flight during that era.

“We acquired the Detroiter from the Ford Museum, and it has the distinction of being the first airplane to make a diesel-powered flight. The Detroiter, only one of two left, was also flown by Lindbergh,” he said.

Herrick has numerous other aircraft, including the only 1929 Kreutzer Tri-Motor left, which is located in Mexico, until it finds a home in the U.S. He also has the only flying 1929 Buhl Sport Airsedan, which he says astounds him.

Herrick looks forward to continuing his pursuit of rare and exotic aircraft.

“It’s what I love to do, and share with people,” he smiles. “I’m humbled to be the custodian of such exquisite aircraft. I’ve been very fortunate.”

For more information, visit www.nationalairtour.org or call 763-786-5004 for a tour of the Golden Wings Museum.