By Di Freeze

It seems that some people are just destined to meet. Take actor Morgan Freeman and businessman and attorney Bill Luckett. Since they met in the mid-1990s, they’ve partnered in a blues club, an upscale restaurant and a couple of different aircraft. If they were different genders, you’d say theirs was a “marriage” made in Heaven.

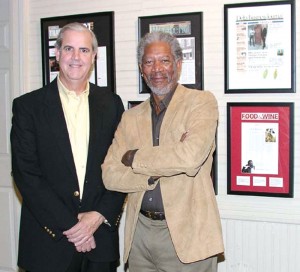

Bill Luckett and Morgan Freeman are partners in Ground Zero Blues Club and Madidi, an upscale restaurant.

“We just really hit it off. As Morgan would say, we started ‘dating,'” Luckett says, in his easy-going Southern drawl. “That sounds a little bit suspect in some circles, but that’s the way he tells it. We got to be very good friends.”

Although all those partnerships now seem so logical and natural, not all of them were instantly apparent. They both loved blues music and good food, but when they met, Luckett had been flying for over two decades and Freeman was enamored with sailing.

Bill Luckett has lived in Mississippi all of his life, except for about six weeks. Although he also has a house and law office in Memphis, he’s lived in Clarksdale for all of that time except about six months.

“My mother and father married, and he was called into the service in World War II,” Luckett said. “My mother went back with her parents to Texas and had me there. Later, when he ended his service, he picked me up and we came back to Oxford, Mississippi, where he finished law school. Then we moved to Clarksdale. He practiced here for about 25 years.”

Luckett’s father was a naval aviator, but mustered out before he had a chance to do “any serious flying.”

“He got moved around and ended up on submarines,” Luckett said.

The fact that his father was a pilot didn’t influence his decision to later fly.

“Although he probably mentioned it, I really wasn’t aware that my dad had even studied piloting,” he said. “I recently found his logbook and it meant a lot more to me now that he’s dead and gone.”

Bill Luckett graduated from Clarksdale High School in 1966, and attended the University of Virginia. Later, he attended Ole Miss Law School (the University of Mississippi School of Law). After graduating in 1973, he joined his father’s law firm.

“There were a number of Lucketts here practicing law at that time—father, wife, uncle down the street,” he said.

He developed an interest in wanting to learn to fly while chartering planes at Clarksdale Fletcher (CKM), to fly to Jackson, Miss., on business.

“I realized I could convert what was a full day driving—doing my business, round-trip travel—into a half-day, by flying,” he said.

Luckett got the opportunity to learn to fly right after he started practicing law.

“My father-in-law was nice enough to offer a Piper 140 to me and his daughter, who was my wife at the time, and another law partner of mine here in Clarksdale,” he said. “He offered to let us learn to fly. He sent a pilot and a 140 over here and said, ‘I’ve leased the airplane for 90 days, and you can call on Carl any time you want lessons.’ My father-in-law had been an Air Force pilot, and served in Africa in World War II. He was very generous to do that.”

Luckett soon began taking lessons with Carl Graves, who was a supervisor working for air traffic control in Memphis at the time.

“I was the only one of us three who finished the program, so to speak, and got my private,” he said.

When he initially thought of the value of flying, he couldn’t help thinking that it just didn’t look that difficult.

“I had a little bit of a head start because I had radio skills I learned in the military, and I knew the phonetic alphabet,” he said. “I knew how to navigate, and instruments were pretty crude back then, too. We were flying off just VORTAC, mostly. We didn’t have GPS or Loran or any of that back then. Now, Loran is even extinct.”

Luckett, who has about 2,700 hours and now serves on the Clarksdale-Coahoma County Airport Board, said that as soon as he got his private license, his law firm bought a Piper Cherokee 6-300 from his father-in-law.

“He moved up to a Piper Seneca,” he explained. “I got time in that one, and then moved into a turbo t-tail Piper Lance, and got a couple of years in that. In the mid-eighties, we bought a Seneca II, which we’ve now put our third set of engines on.”

Morgan Freeman enters the picture

Luckett would eventually have a partner in that Piper Seneca II, a light twin-engine six-passenger aircraft. Morgan Freeman would also invest in a 414 Cessna with Luckett. After Freeman got involved with the Seneca, a few years ago, the aircraft saw more work.

“We’ve repainted and reupholstered it,” Luckett said.

Luckett and Freeman became friends after Myrna Colley-Lee, Freeman’s wife, asked the attorney for some legal advice in the mid-1990s.

“I’d heard that Morgan and Myrna were building a house nearby,” he said. “One day, Myrna called and introduced herself. She told me they were having some difficulty, which translated to some legal matters involved in building a house that they’ve now finished and live in. I eventually met her and Morgan.”

Although he was born in Memphis, Tenn., in 1937, and although his stepfather and mother lived temporarily in Chicago, and in Bruce, Miss., Freeman lived most of his youth near Charleston, Miss., a small town about 40 miles southeast of Clarksdale.

Freeman recalls that as a youth, he spent Saturday mornings doing chores and Saturday afternoons watching cowboy movies. He graduated from high school in Greenwood, about 50 miles from Clarksdale, but would soon leave the Mississippi Delta. In 1955, he considered himself lucky to have traded life in Mississippi for studying dance and theatre arts at Los Angeles City College. In 1967, he made his Broadway debut with Pearl Bailey in “Hello Dolly!” He became nationally known when he created the popular character, “Easy Reader,” on the children’s show, “The Electric Company.”

In 2001, the Mississippi Legislature commended Freeman for his “outstanding career as an actor.”

“Morgan got the longest standing ovation ever offered anyone in the Mississippi House of Representatives, and it was 100 percent attendance,” Luckett said. “He was presented with a resolution honoring him and citing his many accomplishments and basically thanking him for making Mississippi his home. The whole house stood up at least three or four times in what was really about a 10-minute presentation, and they clapped for eight minutes after that. It was a tribute of the highest proportions. He was commended for his wide body of work in film, but also for his local philanthropic efforts since moving back to Mississippi in the early 1990s.

In the resolution, they acknowledged Freeman’s awards including a Tony Award, the Clarence Derwent Award, Drama Desk Award, Obie Award and the Dramalogue Award.

Since 1966, Freeman has been seen in more than 50 films, including the one which really launched his career, “Street Smart” (1987). He’s been busy since then, appearing in films including “Clean and Sober” (1988), “Lean on Me” (1989), “Driving Miss Daisy” (1989), “Glory” (1989), “Unforgiven” (1992), “The Shawshank Redemption” (1994), “Se7en” (1995), “Kiss the Girls” (1997), “Hard Rain” (1998), “Deep Impact” (1998), “Under Suspicion” (2000), “Nurse Betty” (2000), “Along Came a Spider” (2001), “High Crimes” (2002), “The Sum of All Fears” (2002), “Bruce Almighty” (2003) and “The Big Bounce” (2004).

He’ll be seen in at least 10 more movies in the near future, which have either recently finished production, are still in production, or have already been announced. He won the Los Angeles, New York and National Society of Film Critics Awards for best supporting actor and was nominated for an Academy Award and Golden Globe Award for his performance in “Street Smart.” He won his second Academy Award nomination, the Golden Globe Award and The Silver Bear for best actor at the Berlin Film Festival for “Driving Miss Daisy” (he played his same role, that of chauffeur Hoke Colburn, in the stage version). He was nominated for an Academy Award for the third time for “The Shawshank Redemption.” In 1993, he made his film directorial debut with “Bopha!” starring Danny Glover and Alfre Woodard. Soon after that, he formed Revelations Entertainment, a production company.

Although Freeman couldn’t wait to leave home, he later often visited his parents. Then, when his father died, he returned to look after the family farm. He was surprised to eventually discover that coming home, getting away from “the crush,” felt good.

His return to Mississippi would also remind him of another childhood fascination. Besides westerns, war movies had also captivated him.

“I wanted to be a fighter pilot,” Freeman said. “I wanted to strafe freight trains and dogfight and re-fight World War II.”

The movies that inspired him included “Battle Hymn,” “The Bridges at Toko-Ri,” “Strategic Air Command” and “God is My Copilot.”

“I watched anything that had aircraft in it—flying from the ground, from off of a ship,” he said.

That passion didn’t carry over to endless hours building models, however, as it did for many other children.

“I wasn’t too good with model aircraft. I did build one, and it was fine, but I couldn’t gunk it, so I just stepped on it!” he said.

Freeman said he joined the Air Force when he was 18, in hopes of becoming a jet pilot.

“In the fifties, that wasn’t happening,” he said. “I guess if I’d come out of college it would’ve been somewhat easier. I don’t blame the Air Force so much as time and circumstance. I didn’t like military service, so it was a wash anyway.”

After his honorable discharge in San Bernardino, one acting job led to another, and he ended up in New York.

Although it would be decades before he would actually fly, Freeman later discovered a love for sailing. He ponders a similarity between himself and singer Jimmy Buffett, another well-known sailor/pilot.

“Maybe I sort of mirrored Jimmy Buffett in that I discovered sailing when I was about 30 years old and just dove into it,” he said. “I’ve been doing it ever since then. I thought of that as flying, in a sense, because you’re riding the wind. I really like it a lot.”

When Luckett first met Freeman, the actor was splitting his time between his co-op apartment in Manhattan and his boat in the Caribbean. Luckett, who has spent time on Freeman’s boat, praises his abilities—and the boat.

“It’s a beautiful boat,” he said. “When it was new, he sailed it from Rhode Island all the way down in the Atlantic. We’ve had some great sails. He’s an excellent sailor.”

Luckett explains that a lot of the concepts of sailing and flying are the same.

“A wing is a sail, or a sail is a wing,” he says. “Then, there are nautical miles, knots. You have bearing, track and drift. You don’t talk on the radio as actively sailing, but most everything else is pretty similar, in many respects.”

With that in mind, once the two became friends, it wasn’t difficult for Freeman to take up flying. He says that his longing to fly “on this last incarnation” was due to Luckett.

“When we hooked up, he was flying his Seneca all over the place,” he said. “One day he invited me just to go up and fly with him, look around. When Bill and I started tooling around in the sky, he said, ‘You have to get lessons. You have to learn how to fly.'”

Madidi

Before that could happen, the two would hook up in other ways. First, once Bill and Francine Luckett and Morgan Freeman and Myrna Colley-Lee began spending time together, it didn’t take long to realize they were limited to where they could dine, since the area suffered from “a dearth of fine restaurants.”

“There are a few, but we had to travel a long way,” Luckett said. “A lot of the entertaining we do—dinner parties, cocktail parties, social events like that—is here at home.”

Dining out meant Memphis or possibly Oxford—that is, until 2000, when Luckett and Freeman decided to open their own fine dining establishment in Clarksdale.

The idea was appealing to Luckett for another reason; he had always had an interest in architecture, construction and design. It began in the ninth grade, when he started painting houses. Later, during college holidays and summers, he continued painting.

Then, between college and law school, joining the military would give him more practice. He joined the Army Reserve and later the National Guard, and had a year of active duty. While in law school, he went to Officer Candidate School, and became a second lieutenant; he ultimately was the commander of an engineering construction unit, which did several large construction projects.

While in law school, he also continued painting.

“I had a successful paint business going in law school,” he said. “I had a lawyer and three law students working for me. I actually lost money the first month I was a lawyer, because I was making more painting than I was as a lawyer. I think I’m doing better now.”

After dabbling in renovation, in 1992, he completed his first house.

“I was never serious about it until then,” he said. “Then for a while, I was buying another house about once a month. I did about 40, and then started buying old buildings and making multi-unit places out of them. Some buildings may have two units; some might have seven or eight. It’s just a mix.”

He’s renovated five old buildings in downtown Clarksdale.

“Sometimes they’ve been empty as long as 50 years before I converted them,” he said. “Usually, it was just four walls left standing, with a falling-in roof. I like the challenge.

He remodeled the three-story Hotel Clarksdale, turning it into eight apartment units.

“I’ve also done some others in neighboring Lyon, Mississippi,” he said. “I’ve done another four out there.”

And he owns a 101-unit apartment complex in Clarksdale.

“We have fulltime maintenance people,” he said. “Then we have occasional other crews, depending on what I’m doing.”

All that remodeling meant that Luckett felt comfortable renovating an early-twentieth-century redbrick building in Clarksdale into an upscale restaurant, with Freeman as his partner. Madidi, named after a national park in Bolivia, had a soft opening in November 2000, but officially opened in January 2001, with David Krog (formerly of La Tourelle in Memphis) as the chef de cuisine.

In May 2003, Lee Craven replaced Krog. Craven, a graduate of the Hyde Park, N.Y., campus of the Culinary Institute of America, arrived at Madidi after training for three years under French Master Chef Jose Gutierrez, at Chez Philippe, Memphis’ four-star contemporary French restaurant located in the historic Peabody Hotel. There, Craven advanced to sous-chef. He left the restaurant with Gutierrez’ “blessing and recommendation.”

At Madidi, the cuisine is prepared with French technique but with “an eye towards distinctively Southern influences.” Or, as Craven says, they serve food “prepared by weaving the ingredients, history and soul of the South with slight refinements in elegance.”

The atmosphere of Madidi reflects the tastes of Francine Luckett and Myrna Colley-Lee, who is a film set and costume designer and helped with the interior design. Works from local artists grace the interior walls. A comfortable bar and main dining area is located on the first floor, with private dining rooms on the second floor.

Ground Zero Blues Club

Clarksdale is in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, the “part of Mississippi that’s called the most southern place on earth.”

Luckett explains that when the couples first began spending time together, they also “tried” to get out to enjoy blues music, but that wasn’t easy to do either.

“Believe it or not, at that time you couldn’t get reliable or consistent blues music even in Clarksdale on weekends, even though we’re ‘ground zero’ for blues music. This is where the blues music started,” he said.

That changed with the creation of Ground Zero Blues Club, a “juke joint” that opened in May 2001, about two blocks away from Madidi.

“We named our club after what we had always referred to the area generally as,” he said.

Luckett said people come through the area consistently on what’s known as “America’s Music Trail.”

“They either start in New Orleans and go north, and then come to Clarksdale and Memphis, and then Nashville or St. Louis, Detroit, Chicago, or they start north and come south,” he said.

Ground Zero Blues Club is at Highway 61, which Luckett said Bob Dylan and other musicians have sung about in their music.

“Blues turned into rock & roll, basically,” he said. “‘Hound Dog,’ by Elvis, was actually a blues song before that by Big Mama Thornton. Muddy Waters (McKinley Morganfield), John Lee Hooker and numbers of other musicians are from here. The name of the band, The Rolling Stones, came out of a Muddy Waters’ song.”

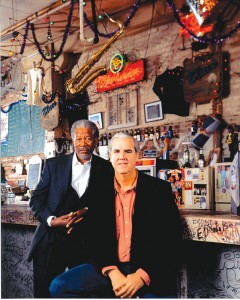

Morgan Freeman and Bill Luckett inside Ground Zero Blues Club, which offers “a true Delta Blues experience at its best.”

Located at Blues Alley, next door to the Delta Blue’s Museum, GZBC features performances by both local and national blues bands, offering a “true Delta Blues experience at its very best.” Luckett and Freeman partnered with Howard Stovall, the former executive director of the Blues Foundation, on GZBC.

Madidi and GZBC have been featured on CNN, Turner South, The Travel Channel and The Discovery Channel, and in Gourmet, Bon Appetit, Food and Wine, Southern Living, Delta magazine, National Geographic Traveler, Flying Adventures, New York magazine and USA Today.

GZBC was the site for filming of “Last of The Mississippi Jukes,” and an eight-part concert film series called “Blues Divas.” Jill Cordes, co-host of the Food Network’s “The Best Of,” visited Clarksdale in May 2002 to tape segments at both Madidi and GZBC for an hour-long broadcast focusing on “celebrity tables.” Rachel Ray recently visited to do a segment on “Inside Dish.”

“It’s a new show they’re just putting together,” Luckett said. “It premieres in November.”

With all the publicity, Luckett admits they still financially have to support both ventures.

“Hence the saying, ‘Do you know how to make a small fortune in the restaurant business? Start with a large fortune,'” he says. “But we’ve been doing this now for three years and hope to keep them going.”

He adds that Ground Zero is going to be expanding.

“We’re going to open a place in front of the new FedExForum in Memphis, as soon as we can get the building up,” he said. “We’re going to be part of a parking garage/hotel complex. It’s going to be called Ground Zero Blues Club Memphis. We may go from there, if that one works. We’re doing that one hopefully to make some money!”

Luckett has also built apartments above Ground Zero Blues Club. Both men spend as much time as possible at GZBC and Madidi.

“Morgan is here when he’s not making movies or on his boat,” Luckett said. “Some years that translates to six months. One year he was here almost the whole year. In just about any movie schedule that goes six weeks or more, they get a break somewhere midway and Morgan will come back for the weekend or something. He’s at these restaurants when he’s in town all the time. Certain stints of time, he’ll be over here seven days in a row.”

In mid-September, Freeman returned to Mississippi after spending time in France. He had about a day to rest up before heading to Memphis with Luckett for a rock & roll gala black tie event at the FedExForum. Following that, they headed to Chez Philippe.

“Lee and his old chef were doing a James Beard regional dinner, which feature chefs from other restaurants as well,” Luckett said. “Morgan and Myrna stayed with us over the weekend in Memphis.”

Freeman finally flies

Luckett remembers the night Freeman decided to take the plunge.

“Morgan had mentioned once or twice in the late ’90s and coming into the turn of the century that one day he might want to learn to fly,” Luckett recalled. “Then, one night, we were at dinner at Madidi, with a group of people. Just out of the blue, he said, “Bill, I’m ready.” He took me by surprise. I looked up, and I said, “You’re ready to leave? Ready to go to the blues club?’ He said, “I’m ready to learn to fly.” I said, “Okay. Two o’clock, tomorrow, Clarksdale Airport.”

The next day, Luckett drove out to where his Seneca II was hangared at Clarksdale Fletcher Field.

“He showed up on time,” he said. “I told him I wasn’t an instructor. I’m multiengine, instrument, single and multi, but I did what an instructor would do. I said, ‘There are some principals involved here,’ and I talked to him about drag and lift and some of those basics, and then took him on a preflight.”

Freeman occupied the right seat, since Luckett needed to be pilot-in-command. According to Luckett, at first, he let Freeman “gently handle the controls.”

“After a couple of times up, which were like introduction rides, I started letting him maneuver the aircraft some,” Luckett said. “Early on, as time progressed, I would let him go a little lower, and I felt comfortable with him doing it.”

Luckett grins and says the experience reminds him of a trial he once attended.

“A long time ago, I was at a trial that involved a lawsuit by a pecan orchard owner against an ag pilot—we used to call them crop dusters,” he said. “The lawyer for the pecan orchard was complaining that his client had lost his pecan crop because the cotton duster/pilot had defoliated his pecan trees in addition to defoliating the cotton crop—you drop a chemical to knock all the leaves off, so you get to the bowls of cotton.

“He had the pilot on the witness stand just grilling him. He was trying to get Jimmy to give him a distance from back from the pecan orchard as he was flying over the cotton, when he would pull his airplane up and turn off the sprayer. Jimmy was just giving him fits right back. The jury’s intent; this got pretty tense. Finally, Jimmy said, ‘This is the best way I can tell you an answer to your question. I stayed out over that cotton. I’m getting closer and closer to those pecan trees. I’d stay down there just as long as I could stand it, and then I’d pull up and turn off the spray.'”

Luckett laughs and says, “With Morgan, we’d be flying over the Mississippi River, and I’d say, ‘Let’s just follow the center line of the river. Now, turn back over the airport. Let’s line up. Let’s overfly the field. Let’s get in the pattern. Let’s land.’ I would let Morgan fly the airplane around, and we’d be coming in on final. He’d be kind of wrestling with it and scared. I would let him keep control of that airplane just as long as I could stand it.”

Freeman said he was “game” and willing to “just go for anything.” He’s thankful that Luckett trusted him.

“I thought, ‘You’re taking an undue chance, letting me take this thing close to the ground,'” Freeman said. “And he did; a couple of times he had to take over and correct so we didn’t wind up out in a cotton field or something. What amazed me most was that he could correct the landing from that close to the ground. Of course, an airplane is like another part of Bill’s body.”

Luckett said it was good training for him to take over at the last second, get the aircraft corrected and back on track, and land.

“But after a while, he got very proficient,” Luckett said.

He said they continued their routine through about eight flights, up until June 2002.

“The last time we went up like that, I said, ‘Morgan, I’m going to follow you around now on a preflight. Then, I’m gonna just cross my arms in the left seat. You take care of it,'” he recalled. “We went down the river, went over to Charleston, on a little strip there, did a touch and go, and flew back. He landed the airplane. I was tempted, but I didn’t ever uncross my arms. He slipped it right in.”

Then, Luckett told Freeman that their “lessons” had to end, since he wasn’t really an instructor.

“He was teaching me, though!” Freeman said. “He had enough courage to let me try and land it. That’s trust!”

“I told him, ‘You have this down now. Now you need to do this with somebody where you can get real credit,'” Luckett recalled.

That someone would be an independent flight instructor named Jimmy Hobson, who happened to taxi up with a student, as Luckett and Freeman stood talking that day.

“He got his single engine land and kept working with it,” Luckett said. “Then he bought into the Seneca with me. He’s got his multiengine now. He has about 560 hours, in two years and three months.”

After getting his private in October 2002, Freeman kept taking lessons with Hobson, a CFII out of Helena, Ark., who comes to Clarksdale frequently.

“He’s a terrific instructor,” Freeman said. “He’s taken me all the way through. I’ve been having a great time. Bill and I also own a twin Cessna 414, which is a great airplane. When we bought the Cessna, the insurance company wouldn’t let me fly it solo, so I had to do one hundred hours with an instructor.”

Freeman says he flies to as many film locations as he can.

“Every opportunity I get, I fly myself,” he said.

“He flies routinely now into Santa Monica, Teterboro and Newark,” Luckett says proudly. “He flew into Houston Intercontinental and just came back last night from there, because he had to take a Continental flight to France and back this week. He’s just a student of it. He loves it. He’s into it big time.”

Luckett says he wouldn’t call Freeman’s involvement in aviation “obsessive,” but he would say he certainly became “preoccupied.”

“He would go on location, say, to shoot a movie, in Hawaii, and fly all over Hawaii,” he said. “He’s flown out of Santa Monica, Van Nuys, all over Southern California, that busy air space there.”

The actor is thoughtful when he hears Luckett describe his involvement in aviation as “preoccupation.”

“When you fly, you spend a lot of time thinking about flying,” he says. “I do, because I’m new at it. If I’m going to fly tomorrow, if I’m going to take a long trip, I will fly it in my head three or four times, just to try and think of everything that you have to think of, because when you get into the airplane, you want everything to be in place.”

He pauses, and then adds, “They say every air crash is a culmination of small things.”

Memorable flights

Freeman says that particularly every flight he makes is “memorable,” but one flight really stands out in his mind. On that flight, on which Luckett wasn’t present, thunderstorm activity facing him meant an alternate landing in South Dakota.

One evening in June 2003, Freeman was returning to Mississippi from Kamloops, British Columbia, where he’d been filming “An Unfinished Life,” which also stars Robert Redford and Jennifer Lopez. Because of the weather, he changed flight plans and landed at Wagner, S.D., instead of his scheduled refueling stop in O’Neill, Neb.

“It was dark, so we just decided to go to the nearest available airport and land,” he said.

Wagner Municipal Airport Manager John Otte was incredulous when Freeman stepped out of the plane, but disappointed to be without a camera. Freeman, knowing he’d be spending the evening in town, graciously offered to pose for a picture the next day, while he refueled. He also caused a stir at the local Super 8 Motel, where he spent the night. The town’s people won’t forget that visit, and neither will Freeman.

“That was the first long trip I’d taken, and we were in the Seneca, which is not pressurized,” he said. “We flew over the Rockies in Canada, so we had to go up about 16,000 feet. It was verrrry cold. I don’t think that Seneca had ever been up that high. We were listening to the starboard engine miss about every minute or so. But it was okay. That was memorable, because going up that high, we were in the clouds, and it was freezing cold. We had to turn on the pitot heat and we didn’t have anti-icing so we were watching very carefully for ice. Then, that landing at night at the tiny air strip. I’ll probably remember that one for a while.”

Another interesting flight, which is also the farthest distance Freeman has flown, was with Luckett to Virgin Gorda, in the British Virgin Islands last November. Freeman flew about 80 percent of that total trip, with Luckett flying a few legs to give him a rest.

“Bill was selflessly trying to help me build up hours,” Freeman explained.

Luckett happened to be flying the Seneca during the most harrowing leg of the trip. He says he was lucky to have Freeman in the right seat for that particular leg of their adventure.

“He was working the Garmin 530 and I was trying to keep the airplane in the air,” he said.

During that flight, the men made multiple stops.

“We stopped at Daytona to visit his wife’s dad, and then we flew down to Fort Pierce, Georgetown Exuma, Providenciales and the Turks and Caicos (Islands),” Luckett said.

Although they were just going to make a fuel stop in Providenciales, they were weathered in there.

“There was a big tropical storm over Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands so we stayed a couple of days waiting it out,” he said.

Once back in the air, they headed toward Beef Island Airport, near Road Town, Tortola. They were communicating with San Juan Center and had been assigned an altitude of 5,000 feet to go directly to Road Town, but as they started getting closer, the weather began deteriorating.

“I was trying to call back to center to divert to St. Thomas or somewhere else, but we couldn’t raise anybody on the radio,” Luckett said. “There we were flying into weather, and on an IFR flight, unable to talk to anybody. I called the tower at Road Town and got them to get on a land line and contact San Juan. They did, and came back and gave us an alternate frequency. We were able to make contact to get clearance to land, but then our problems were still compounded because we had bought approach plates in Florida for the whole Caribbean and this particular airport’s approach plate wasn’t in the booklet.

“The tower was very helpful to us there, in giving us a minimum descent altitude. We were able to track—I would call it a ground track, but where we were, it was mostly a water track—coming in to the airport itself, because there are mountains around it. It’s down at sea level.”

Unable to see anything, they finally were able to get down legally low enough to break out.

“But we were in awful rain and made a couple of real tight turns,” he said. “Morgan was a great help on that landing. He was counting down miles and helping me count down the altitude. We were in some pretty rough weather. We were able to land it, but flights right after us were unable to get in. It was raining so hard we couldn’t even get out of the plane without getting totally drenched. We weren’t in a thunderstorm, fortunately, but we were in zero visibility down to minimum descent altitude, at an unfamiliar airport, with mountains around, without the approach plate. That’s a little hairy.

Coming back, the men made three or four stops.

“Going down, because we were going IFR, I think we were flying at 9,000 and 11,000, and 10,000 to 12,000 coming back,” Luckett said.

Nowadays, with the 414, Luckett said they go up to altitude and get in the 20,000s.

“We’ve both been up to flight level 230 in the 414,” he said.

Freeman also owns a Piper Arrow, but has plans to sell it. For the last several years, he’s also had a fractional share in a Beechjet 400A and a Hawker 800XP with Flight Options.

“We just sold out of the Beechjet last week, and we just announced that we wanted to sell his interest in the Hawker, too,” Luckett said. “Now that he’s flying himself to LA and New York, he really doesn’t need those airplanes.”

Flying the T-37 “Tweet”

Recently, Freeman and Luckett had yet another fabulous adventure together. They were invited to Columbus Air Force Base to fly the T-37 “Tweet.”

“A guy who’s known as Poe, who was an air traffic controller there and who lives in Clarksdale now, set it up for us,” Luckett said.

Columbus Air Force Base is home to the 14th Flying Training Wing of Air Education and Training Command’s 19th Air Force. The wing’s mission is specialized undergraduate pilot training in T-37 “Tweet,” T-38C “Talon” and T-1A “Jayhawk” jet trainers.

“The base commander met us with open arms,” Luckett said. “We went through physicals and ejector seat and parachute training, and had our masks and flight suits fitted.”

On the morning of August 12, at 0730, Luckett and Freeman “reported for duty.”

“After the training, we went up for an hour,” Luckett said. “I had a captain and Morgan had a captain. It’s a side-by-side cockpit arrangement. They were in the left seat, the pilot-in-command’s seat. We had a ball. Of course, those guys are real jockeys; they know their stuff.

“We took off at Columbus, in formation, with Morgan and Captain Lee Glenn in the front, and Captain John Speer and me in the back. We’re getting up to the MOA (Military Operations Area), which is 8,000 and above. We sort of trailed each other, and then climbed down in tandem. Once we got into the MOA, we resumed a tighter formation.

“At that time, these guys used this incredible sign language. They nod their head. They kind of glance at each other. They use hand signals. They wriggle the tail of the plane. They have all these little mechanisms of communication. Of course, they could talk to each other, but that’s not cool. They like the element of surprise. So, they kind of give a little head shake at each other, and then, away you go.”

After about 30 minutes, Luckett and Speer took the lead.

“We’re up at 13,000, 15,000 feet, with solid white underneath, because there’s a solid cloud layer below us,” Luckett said. “There’s blue sky above. We get wingtip staggered to wingtip and all of a sudden that guy just kind of nudged his hand. Cockpit to cockpit, 300 knots at 13,000 feet, these guys are looking at each other, just like we’re going down the interstate, looking across at the other car. They just kind of wink or blink; they already know what they’re getting ready to do. They put you through it—straight up, straight down, sidewise, looping—all kinds of fun stuff.

“The ice particles are coming out of the air conditioner system, like floaters in space. All I knew after a while was blue was up and white was down. The dials on that altimeter were spinning like you couldn’t see it. The G’s were up there in the 4 and 5 range. You couldn’t even lift your hands out of your lap. It was exhilarating.”

Luckett said they were told that 90 percent of new pilots and passengers get sick, but they didn’t.

“We both resisted getting sick,” he said. “I guess I have a strong stomach because I’ve been flying a long time, and Morgan’s been a sailor a long time and a pilot as well.

Possible future plans

Freeman and Luckett have agreed to participate in a round-the-world flight being organized by Alex Major and the King Air Foundation, a Mississippi nonprofit corporation.

Since 1985, Major’s company has owned King Air LJ-1, which Olive Ann Beech, the wife of Beech Aircraft Company founder Walter Beech, used as her personal corporate transport. In 1990, he brought in a partner, Dr. Fred Pasternack, to assist in funding the continued preservation of this piece of aviation history. A restoration process has begun that will culminate in an historic flight. Following that flight, King Air LJ-1 will be donated to an unspecified museum.

The purpose of the flight is to honor the history and legacy of Walter and Olive Ann Beech, the Beechcraft brand and the world’s most popular turboprop aircraft, the Beechcraft King Air; to raise money for spinal-cord research and children’s medical charities; and to “spread goodwill for general aviation around the world.”

Luckett said they accepted Major’s offer to fly a leg of the trip on condition that the King Air is made airworthy.

“He’s recruiting celebrity pilots, and other pilots, like me, who are not necessarily celebrities, but who have an interest in aviation and who want to ride and have some fun with it, to take different legs,” Luckett said. “We got the first choice; we picked Prague to St. Petersburg, because I want to see the Hermitage Museum in St. Peter, and Morgan has been to Prague before.”

At the present time, Major is also recruiting people to help in the rebuilding process.

“Alex is dogged in his pursuit of this,” Luckett said. “He’s dedicated to getting it done. We’ve tried to help along where we could. It’s just something that’s going to take some time and a lot of effort getting it all put together.”

Although Freeman and Luckett do a lot together, there are some areas where they agree to disagree. For instance, Luckett loves to fish.

“Morgan doesn’t go fishing with me,” he said.

He said there was one exception, but the cameras were rolling.

“We did do a segment for Turner South’s ‘Off the Menu’ where we were crappy fishing,” he said.

Freeman also doesn’t share Luckett’s love of motorcycles.

“I have a very powerful motorcycle,” says Luckett. “It’s a Honda VTX 1800cc. But Morgan doesn’t ride. He had to ride one in a movie, and he said it almost got away from him. He loves horseback riding though. I’ve never been riding with him. Morgan also has a fabulous BMW 740 that he loves to drive. I think it goes faster than some of the airplanes he’s flown.”

- Master Sgt. Curtis Chiles conducts egress training for actor Morgan Freeman before his orientation flight in a T-37 Tweet Aug. 12. Freeman also ate lunch with about 50 airmen from the base. Chiles is assigned to the 14th Medical Operations Squadron.

- Morgan Freeman and Bill Luckett admiring student class patches in the Operations Group Building. Each class of student pilots creates a patch that they wear during their year of specialized undergraduate pilot training at Columbus AFB.

- Bill Luckett and Morgan Freeman co-own this Cessna 414 as well as a Piper Seneca II.

- Bill Luckett and Morgan Freeman stepping out to prepare for their T-37 Tweet orientation flights.

For more information on Madidi and Ground Zero Blues Cub, visit [http://www.madidires.com] and [http://www.groundzerobluesclub.com].