By Di Freeze

When Sydney Pollack, Academy Award winning director, producer and actor, thinks about flying, a couple of words come to mind. With the kind of flying he does, he says it’s important not to get those words out of order.

Sydney Pollack became interested in flight when his father-in-law gave him a ride in a Boeing Stratocruiser. The next turn of events that led to his “obsession” with aviation was a ride in a Cessna 206 he took with screenwriter and producer Roland Kibbee.

“I would say it’s first the word ‘careful,’ followed by ‘freedom,'” he said.

That kind of flying is from the left seat of a Cessna Citation X, a mid-size aircraft that is the fastest business jet available today, which he’s been piloting for three years. Pollack, who bases his jet at Clay Lacy Aviation, at Van Nuys Airport, was one of many people interviewed by Brian J. Terwilliger for his film, “One Six Right,” which traces the origin, history, glamour and activities of the 75-year old airport. Pollack says there are various reasons he’s made VNY his home over the years.

“It’s convenient,” he said. “It’s a good airport and I know the people there. That’s where I got started flying. What kept me there initially was the place that I was renting airplanes from in the sixties and seventies. Then, I chartered out of there in the seventies and the eighties. I started hangaring my plane there in the nineties.”

Pollack’s 19 films have received 46 Academy Award nominations, including two for Best Picture. “Out of Africa” (1985) won seven Oscars including Best Picture and Best Director. He won the New York Film Critics’ Award for his 1982 film, “Tootsie,” and the David di Donatello Award for “Three Days of the Condor” (1975). He’s also won the Golden Globe for Best Director twice, the National Society of Film Critics’ Award, the NATO Director of the Year Award, and prizes from the Brussels, Belgrade, San Sebastian, Moscow, and Taormina Film Festivals.

The American Film Institute voted “Tootsie” the #2 Comedy of all time, and “The Way We Were” (1973) and “Out of Africa” were both included in the AFI’s top 100 Romantic Films of all time. In 2000, he was awarded the Directors Guild of America John Huston Award by the Artists Rights Foundation. Other acclaimed films he’s directed include “Absence of Malice,” “They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?” and “The Firm.”

As an actor, he appeared in Woody Allen’s “Husbands and Wives,” Robert Altman’s “The Player,” Robert Zemeckis’ “Death Becomes Her,” Steve Zaillian’s “Civil Action,” Stanley Kubrick’s “Eyes Wide Shut,” and Roger Mitchell’s “Changing Lanes.” On television he has appeared on “Mad about You” and “Will & Grace.”

In 1985, Pollack formed Mirage Productions. Under that banner, he has produced “Presumed Innocent,” “The Fabulous Baker Boys,” “White Palace,” “Major League,” “Dead Again,” “Searching for Bobby Fisher,” “Sense and Sensibility,” “The Talented Mr. Ripley” and “Cold Mountain.”

It’s possible that only his success in the film industry has kept him from getting even more involved in aviation.

“It would’ve been great to be a professional pilot,” he said. “I think that would’ve been fun.

He says that these days he doesn’t do any “pleasure flying,” since it’s impossible to accomplish when you’re flying a Citation X.

“My flying now is all business flying,” he said. “It’s pretty hard to fly a jet for pleasure; you can’t stay low enough. Once you’re up that high, there’s no such thing as pleasure flying. At the altitude you have to maintain, you can’t screw around. You can’t even turn left or right. You’ve got to stay there, because you’re in a crowded sky.

“With RVSM (Reduced Vertical Separation Minimum) coming up, your separation is only going to be 1,000 feet, instead of 2,000 feet, so the accuracy of your flying has to be incredibly good. You can’t do the kind of wish flying that you used to. You can’t get in a plane, go out over the ocean and horse around.”

Pollack says he takes his Citation X almost everywhere.

“For example, tomorrow, I’ll fly to Toronto, to the Toronto Film Festival,” he said, in mid-September. “I’m doing a presentation there and I have to see a few films. I take it to Europe. When I go, as I have most often, to five or six countries, then I take the plane.”

However, he said there are times when it’s just not worth it to take the Citation X. For example, he recently directed “The Interpreter,” a political thriller starring Nicole Kidman and Sean Penn that’s due out in early 2005. Five days of filming were shot in Mozambique in August.

“It wasn’t worth it to take the plane all the way to South Africa, but if I was going to move around in Europe or in the African continent, I would’ve taken it,” he said. “If I’m going to fly to London for two days, there’s no sense. It’s better to get on a British Air flight, go to sleep, get off, do your work and come back.”

The beginning of an obsession

Pollack said he had a normal kid’s interest in aviation, but it wasn’t until after he got married that he really got interested. His wife’s father, a general in the Air Force, had a Boeing Stratocruiser, and gave him a ride in it. The next turn of events that led to his “obsession” with aviation was a ride he took with screenwriter and producer Roland Kibbee.

“I was directing a television show that was produced by Roland,” he said. “He owned a Cessna 206 and invited me to go flying. It was in the middle of the afternoon, on a beautiful day. We were working on the script, and he was sort of looking longingly out at the sky, and obviously not wanting to be working, but to be flying. He just said, ‘Come on. Let’s go fly.’ I’d never been flying, really; not in that sense. That’s how it started.”

Kibbee took him out to Van Nuys Airport.

“He kept his plane at a little place called Skyways, which was both a school and a Cessna dealership,” Pollack said. “I got the bug as soon as I went flying.”

He immediately asked about lessons, and found out they were expensive.

“At least at the time they were expensive to me,” he said. “It wasn’t a lot by today’s standards; I think it was 25 dollars an hour for a Cessna 150, with an instructor. I would save up and take a lesson about every two weeks.”

At that time, the manager of the Cessna dealership was Ed Connelly, who gave Pollack his first lessons. Pollack got his private pilot’s license around 1964; he said the experience was different than it would be now.

“When I learned to fly, you used to have to actually demonstrate spins and recoveries in order to get your pilot’s license,” he said. “Spins are outlawed now. That’s too bad, because it was invaluable training. It was wonderful in the sense that it accurately taught you how to get out of an unusual attitude. It kept you from panicking, when the plane gets upside down or twirling around, and you don’t know where the horizon is. You have some sense of what to do, if you’ve actually been through it. It’s hard when you just do it off a book.”

Pollack flew often, and after getting his multiengine rating, flew Cessna 172s, 182s, 206s, a 310 and other multiengine aircraft, which he rented. Occasionally, he flew to film scout locations.

“For ‘Jeremiah Johnson’ (1972), I flew a Cessna Skynight up the Rocky Mountain range,” he said. “We ended up in Canada looking for the place to shoot the film. We also shot it in Utah.”

He spent considerable time looking at other possible locations. But in the 1970s and 1980s, Pollack found it hard to stay current with his flying.

“Once I got out of television and into film, the films took me away from flying for a long time,” he said. “I was flying sophisticated enough equipment that I couldn’t stay current. I would have to come back after a six- or seven-month’s absence, and couldn’t just walk into a multiengine, high-speed airplane. I was back to hiring instructors again, and I thought, ‘This is crazy. I can’t keep up. I’m just going to lay off for a while.”

In the 1980s, Pollack’s studio started chartering aircraft, both for location scouting and also for tours he would take, opening movies around the country or in Europe.

“I chartered here in the States a lot from Clay Lacy,” he said. “In Europe, I chartered all over the place.

One of the planes he occasionally chartered was a 25-year-old Lear 25 (138JB), which Lacy operated for the owner.

“It was an older airplane, but it was the plane I really learned to fly jets on,” Pollack said. “I started by sitting in the right seat on some of the charters, and then I decided to take it up in earnest; I wanted to go to flight school. Just before I did, I bought that very airplane from the owner.”

Pollack needed a copilot, but that situation was soon remedied. Connelly, who had held a longtime desire to be an airline pilot, had left Skyways to fly for TWA, at age 31. He flew for that airline for 25 years, before deciding to take early retirement, due to turmoil in the industry and the threat that the airline might go bankrupt, and his pension might not remain in tact. When he heard that Pollack was buying a Lear 25, in 1989, he offered his service as copilot. At that point, Connelly was flying as captain in 727s.

“He was also rated in the L-1011 and 707s,” Pollack said. “We worked out a deal and we’ve been flying together ever since.”

Although the 25’s range “wasn’t the best,” they flew it all over Europe.

“I kept the 25 for about two years, and then I bought a 35, and flew that for about two or three years,” Pollack said. “Then I bought a 55 and I flew that for about four years; then I bought a Lear 60.”

Pollack kept the Lear 60 for about a year, and then acquired his Citation X, which is about “twice the size” of the Lear 60.

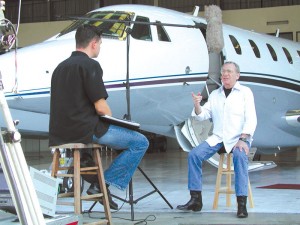

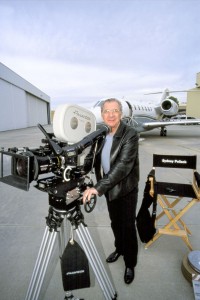

Before acquiring his Citation X (background), Sydney Pollack (left) owned a Lear 25, 35, 55 and then 60.

“It has a longer range,” he said. “It has different technology and different aerodynamics, but it also costs twice as much. It took me a long time to decide whether to pay that much for an airplane.”

Pollack said that at the time he considered other jets, including the Falcon.

“I decided that my best bet was the X, and for the most part, it’s a very good airplane,” he said. “Everybody that owns an airplane has headaches. You sometimes have run-ins with the factory or with the management of a company in terms of what you think they ought to be doing for you, but for the most part, I’ve been pleased with it.”

Pollack, who has about 3,000 hours, says that the most difficult thing about flight training is that he has “a day job.”

“Everybody that I’ve gone to school with has been professional pilots,” he said. “I am not a professional pilot. I have another job, but I have to be as good as those guys, otherwise I can’t fly. I’m trying to pull two trains here. Most guys that are professional pilots spend all day flying. I don’t do that; I’m directing films, reading scripts and so on, but I have to come up to their standards.

“I have to get a rating at the toughest school in the world—FlightSafety. They don’t give those away. They don’t care who you are, or what you’ve done, because they have to protect themselves in terms of insurance. If they licensed you and you did something really stupid, the insurance company could say you weren’t trained, and then they’d be liable. They don’t let you miss anything on the test. It’s pretty tough.”

He said the two-week Lear school was grueling, but the 21-day Citation X course was worse.

“I thought I was going to kill myself,” he said. “It’s hard to get the ratings, but for me, it’s doubly hard, because I’m going to school with professionals who have five, 10, 15, 20 thousand hours, and guys who have already been rated in 10 other jets. I have to work like hell, and I go back to recurrent every year.”

Although flying is a lot of work these days, he says it’s definitely worth it, and has given a lot of thought as to why it is.

“It started out that I just loved flying,” he said. “Then, it graduated from loving the flying to the sense of freedom of it, and sort of sensuality of it, to a sense of pride in being able to do it well as it got more difficult, to a sense of utilitarian effect of it—where I was really using it as a way of changing my life and my time, and what I could and couldn’t do.

“Then, it became a combination of the satisfaction of being able to do a very complicated thing well—that is high-performance jets in instrument weather—then accomplish a task in half the time it would take you in a commercial airliner. It’s all of those reasons; there’s a certain pride to it. It’s no longer a question of going out and boring holes in the sky, like you used to do in a high, fixed-wing propeller plane. It’s a different kind of flying.”

The Lafayette, Ind., native knows firsthand the dangers involved in aviation. In 1993, his son Steven was killed in a plane crash. Although devastated by his death, even that couldn’t diminish Pollack’s love for flight.

Pollack says that to him aviation is an “obsession.”

“I can’t go near an airplane without stopping, or I can’t see an article about aviation in a paper—it doesn’t matter whether it’s a plane crash or announcement of a new plane—without my eye going to it right away,” he said.

Pollack ponders the question as to what about aviation evokes feelings described by pilots often as passion, obsession and addiction.

“Because you’re somewhere that you weren’t biologically designed to be,” he says. “You’re treading in terrain that another animal is designed for. In a way, it’s a very liberating experience. You break away from all the restrictions of gravity. You go at speeds you can’t possibly approach. You also have this sensation—and I don’t mean it as a pun—of ‘flying.'”

As an example, he quotes, “He flies through the air with the greatest of ease, that daring young man on the flying trapeze.”

“Flying, from birth, is a kind of sensual feeling,” he said. “When your dad or mom used to pick you up and throw you up in the air, you squealed. There was such a sense of delight in breaking free. Here, you’re doing it, like a wish. It’s like dreaming. You point over to a cloud, and you just point the plane over there and push the throttle forward, and there you go; or you roll over and over, or do a loop or something like that.”

Pollack says he hasn’t done that kind of flying lately, of course.

“You can’t do that stuff in these little jets, but you still have the sense of terrific accomplishment, when you find your way through weather and across a continent and an ocean to another place you’ve never been, and do it, very precisely, within a minute or two of your estimate, with the right amount of fuel left, and you’ve made all of your decisions correctly,” he said. “You’re always trying for what we call a ‘perfect flight.’ It feels great when you do it, but it very rarely happens. You usually screw up something.”

“Out of Africa” clearly reflected some of the director’s love for flight. In the movie, Robert Redford shows Meryl Streep the beauty of Africa, “an experience you can only appreciate from being in a plane,” according to Pollack. Pollack has seen that beauty from various aircraft, including a Stearman. He says he loved the open-cockpit experience.

“That’s a plane you can’t hurt,” he said. “You can roll it around and sit it on its tail and do all kinds of things to it. You’re not going to pull it apart. You get used to being careful.”

One of his more memorable flights was in an F-16 out of Point Mugu Air Station.

“They had a VIP program where occasionally somebody like myself, who had some visibility and was trained already as a pilot, could apply for a ride in a plane,” he said. “They gave you a briefing over a period of a week about the dangers of high-altitude flying. You had to get a mask on and go into a high-altitude chamber. Later, they gave you a medical. They checked your medical certificate and made sure you knew how to get out of the plane if it went down. Then I had to wait for another four or five months until a ride came up.”

Pollack went to school on an F-16, and got about an hour and a half in one.

“I logged about 40 minutes in stick time,” he said. “It was great. The course itself was interesting. It was more than anything a survival course. How do you go in water? How do you get out of the plane? I had to go in a pool and show that I could swim with a parachute on, and roll over and get out of a plane from underneath the water, and things like that. Mostly it was trying to get out of an ejection seat without getting your elbows blown off. That was about five years ago, before the government got so uptight.”

Pollack says there isn’t necessarily a particular flight that stands out in his mind as being the “most memorable.”

“Sometimes it’s the time of day that’s magical,” he said. “You’ve been on a long journey and you’re arriving just at sunset and you turn final, and line up with the runway. It’s a very satisfying feeling. Or the first leg of a transatlantic trip—usually it’s from here to Gander (Newfoundland)—we usually leave at 9:30 or 10 at night, so we can make the ocean crossing in the day, and we land just at daybreak. Coming across down into that tundra, that vast flat land with nothing much in it, and the way the light looks, just at dawn, in winter, is quite beautiful. It’s something that very few people get to see.”

Passing the passion along

Pollack likes to say that Harrison Ford and Tom Cruise saw that “someone as dumb as me could fly,” and decided they could too.

“I’m only half joking when I say that,” he said. “What I mean is that people grow up thinking pilots are all blond with epaulettes on their shoulders—Arnold Schwarzenegger or something. That’s not necessarily true. You can be a regular person and fly an airplane. You just have to be interested in it, and have a certain amount of technical acuity and coordination.”

While shooting “The Firm” (1993) in Memphis, Cruise had a chance to ride in the aircraft Pollack had at the time.

“While we were there, he had a Gulfstream and a crew flying it,” Pollack said. “I had my Lear 35 at that time. It was in the film; Cruise rode in it, in one of the sequences. Then, when we had a weekend sometimes, we would rush like hell to the airport; we would practically race each other. The police would give us an escort. He’d get in the Gulfstream and I’d get in the Lear, to come home for a two- or three-day weekend.”

Pollack said Cruise was intrigued by the fact that he was personally flying his aircraft.

“We opened the picture on July 4th. It did very well on its opening weekend,” he said. “His birthday is in July. For his birthday, I gave him a flight bag and an E60 computer, and all those kind of basic tools. I gave him a video from a private pilot course. Less than a year later, he had his license and was flying. Now he’s quite advanced.”

Although he hasn’t flown with Cruise in his P-51 Mustang, he says he has flown with him often in his Pitts, an aerobatic plane. He said a similar thing happened with Ford, whom he directed in “Sabrina” (1995) and “Random Hearts” (1999).

“Harrison flew with me in the 55 and the 60,” he said. “Then he decided to go off and get his license.”

From a copilot’s point of view

Ed Connelly, who has over 28,000 hours and maintains the aircraft Pollack owns, says his boss technically isn’t a “professional pilot,” but you’d never say he isn’t “professional.”

“Sydney is a very good pilot,” he said. “It’s not flying with somebody who’s not a pro. He is totally professional.”

Connelly says Pollack’s professionalism is evident in the fact that when they have a trip to make, he shows up at the airport early to check out everything.

“He isn’t an owner that just jumps up on the left seat and says, ‘Okay. Let’s go,'” he said. “He knows his stuff. There’s no doubt about it.”

Connelly delights in planning for their trips, and says that Pollack gets involved there as well.

“Flying a European trip, there’s a lot of planning,” he said. “There again, Sydney knows we have a long, complicated trip, and he’ll come out to the airplane two days early. He’s so organized; he’ll have everything at your fingertips. That’s what a director does.”

He smiles and says that another example can be found in a conversation overheard at FlightSafety.

“I was there with him once and there were a couple of instructors standing around the corner,” he said. “They didn’t see me coming. One of the instructors said, ‘Oh, you have Sydney Pollack in your class?’ The other one said, “Yes.” He said, ‘You’d better get in the books and know your stuff.’ He asks questions; he wants to know it all. And then he has this wonderful memory, so when he studies, it doesn’t take him long. He studies the week beforehand and he has it.”

Connelly says the reason Pollack has acquired five different aircraft over the years is that he is very in tune with their need.

“He’d see where we could be somewhat vulnerable because of range in an airplane, and we’d move up to the next one,” he said.

Connelly says he doesn’t share in the flying when they’re making a trip.

“That’s his passion—and he has an 18 million dollar airplane,” he grins. “He does all of the flying.”

However, Pollack recognizes that his copilot could easily lose his proficiency by not doing any flying on his own, so he allows him to use the airplane for training purposes.

“He gives me a training program that gives me unlimited time at FlightSafety,” he said.

Connelly also keeps in practice by flying a friend’s Great Lakes biplane, which he formerly owned. His highest compliment for Pollack is the fact that he actually “likes” flying with him.

“Most pilots I’ve talked to who have flown with their aircraft owners say, ‘I don’t think I want to do that again. I’m delighted to fly with Sydney,'” Connelly said.

- The Citation X on the ramp at Van Nuys Airport with Clay Lacy’s DC-3.

- The interior of Sydney Pollack’s Citation X.