|

When Arnold Palmer was recently asked what he “never” travels without, he said, “Pete Luster, cell phone and golf clubs.”

Clubs? That’s easy to figure out. The cell phone? At 75, he’s still an incredibly busy man. And Pete Luster? He’s the last in a short list of chief pilots—a “good little fraternity”—who have shared the cockpit with Palmer. “I go where he goes,” Luster confirms. For Luster, that means splitting his time between Orlando, which he calls home, and Latrobe, Penn., Palmer’s hometown and home of Arnold Palmer Regional Airport. Luster, a former military pilot who has held other corporate flying jobs, says he sees one big difference in working for Palmer. |

“The unique thing about being Arnold Palmer’s pilot is that he’s the other pilot,” he said. “That’s significant. When the boss is sitting in the backseat, which is the case in most corporate jobs, you can sometimes get away with screwing up. When he’s sitting right there beside you, it’s pretty tough to do that!”

Palmer has spent a lot of time in the air, much of it in the left seat. The legendary professional golfer has about 18,000 flight hours, built up over five decades. He pauses when asked if he’s been an inspiration for other golfers to take up flying.

“I can’t answer that,” he said. “The inspiration might be to get to where they want to go in a hurry!”

Since several golfers have also become pilots, some people have speculated about the mindset required of each.

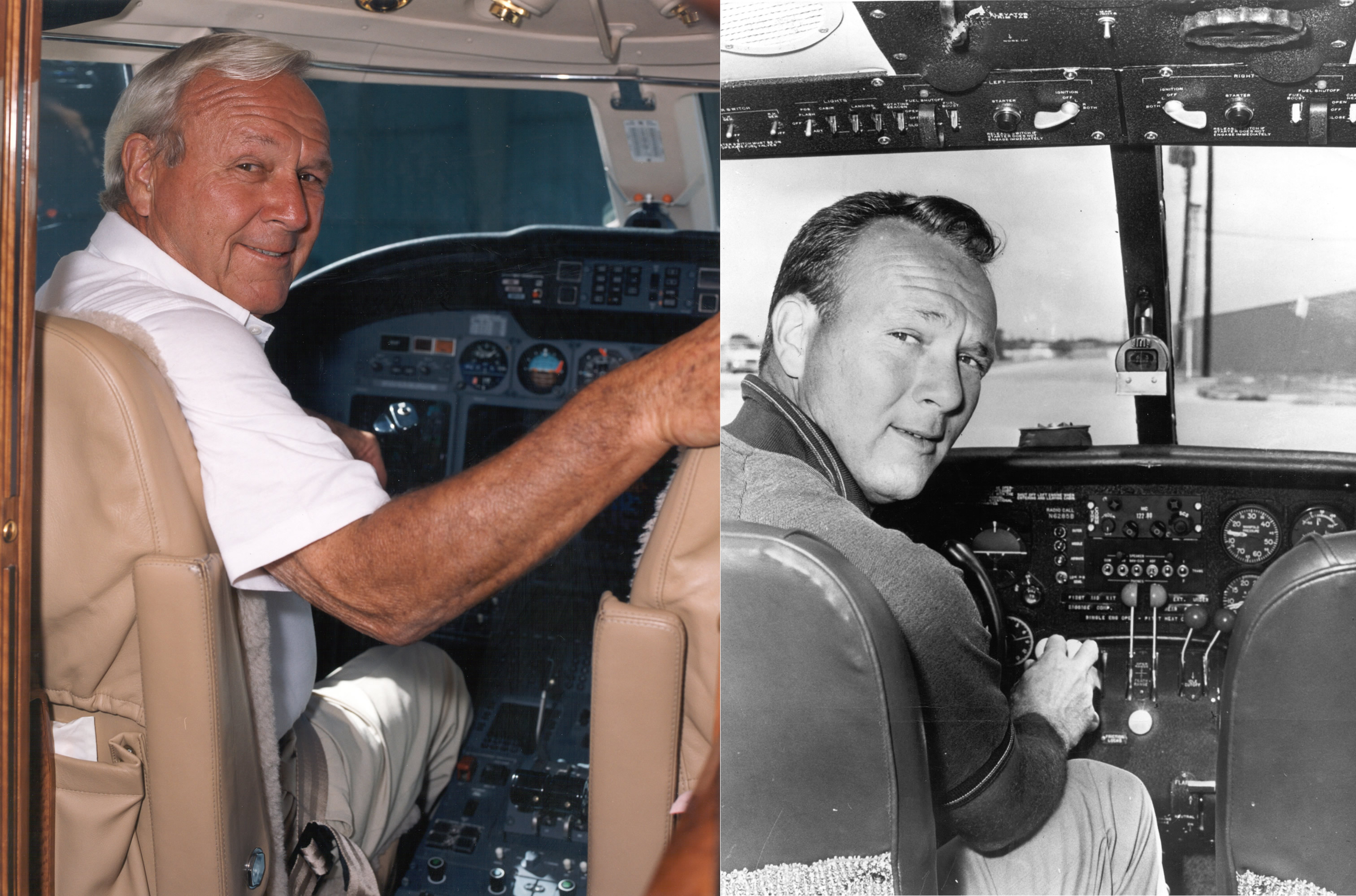

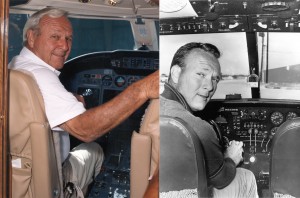

Arnold Palmer acquired his first jet, a Jet Commander, in 1966, and took possession of his first Citation X in 1996. He’s shown in the cockpit of both.

“I think if you stretch it a little bit, there are some similarities between flying and playing golf,” Palmer said. “My father always said (90 percent of golf) is played from the shoulders up. I think flying is something very similar. You have to use your head to fly.”

One of the best-known sportsmen and small business owners in the world, Palmer has won 92 national and international championships, 61 of them on the U.S. Tour (starting with the 1955 Canadian Open). His golf titles include four Masters, two British Opens and the 1960 U.S. Open. He also has represented the United States seven times in the Ryder Cup Matches as either a player or captain.

He was recognized for his achievements in an Associated Press poll as the “Athlete of the Decade” for the 1960s. During his career, Palmer has received virtually every national award in golf as well as the Hickok Athlete of the Year and Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Year in 1960 (after that stellar season).

Between 1960 and 1963, his hottest period on the Tour, he landed 29 of his titles and collected almost $400,000. He was the leading money-winner in three of those four years and twice represented the U.S. in the Ryder Cup Match. A charter member of the World Golf Hall of Fame, he’s also a member of the PGA Golf Hall of Fame and the American Golf Hall of Fame.

His awards include a Lifetime Achievement Award, PGA Tour, 1998, the Donald Ross Award, American Society of Golf Course Architects, 1999, and Patriot Award, Congressional Medal of Honor Society. He’s a past honorary national chairman of the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation and the Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children and Women.

Palmer, who underwent successful prostate cancer surgery in 1997, and has become a strong advocate of programs supporting cancer research and early detection, is president of Arnold Palmer Enterprises, a multi-division structure encompassing much of his global commercial activity that is centered in Cleveland. He has been involved in automobile and aviation service firms over the years and still is the principal owner of Arnold Palmer Motors, an automobile dealership in Latrobe. In addition, he is the sole owner of Latrobe Country Club, majority owner of the Bay Hill Club & Lodge, part owner of the Pebble Beach Golf Complex and the consultant to and former chairman of The Golf Channel. He heads Palmer Course Design Company, which has designed or remodeled some 250 golf courses around the world, and has ties to Arnold Palmer Golf Management Company and Arnold Palmer Golf Academy.

During his early days on the Tour, Palmer’s rapidly growing business interests took flight through his impetus, under the guidance of the late Mark H. McCormack, his business manager, and IMG (International Management Group), McCormack’s wide ranging organization, which today is the world’s premier sports and lifestyle management and marketing firm. IMG was sold in September 2004 to New York investment firm Forstmann Little and Co.

McCormack and Palmer knew each other through college golf. Shortly after that, McCormack asked Palmer to join him in putting together a company representing golfers. But when McCormack expressed that he wanted Palmer on an exclusive basis, Palmer, knowing McCormack had another partner, and that the two of them represented about 10 or 12 golfers, told him he could have an exclusive with him if he gave up everybody else—including his partner.

McCormack later agreed to that. When he asked for a contract, Palmer said a handshake should do, and with the handshake, became his client. Palmer would later say that although McCormack was very smart, he added a good dose of “common sense” to the partnership.

The early days

Born on Sept. 10, 1929 in Latrobe, Palmer grew up in a small house near the then sixth hole of Latrobe Country Club. When he was a young boy, his father worked at the club as a golf professional and course superintendent. Arnold Palmer would often sit for hours watching golfers tee off. He began caddying at the club at 11 and worked at almost every job there in later years.

He concentrated on golf in high school and won his first of five West Penn Amateur Championships when he was 17. He competed successfully in national junior events and at Wake Forest College became the number one man on the golf team and one of the leading collegiate players of that time.

When Bud Worsham, a close friend and golf teammate, died in an automobile accident, a troubled Palmer withdrew from college, during his senior year. He began a three-year stint in the U.S. Coast Guard. His interest in golf was rekindled while he was stationed in Cleveland. After his discharge from the service, he returned to Wake Forest to finish his education, but left before graduation and began working in sales in Cleveland.

In the late summer of 1954, he won the coveted U.S. Amateur Championship in Detroit, following a second straight victory in the Ohio Amateur earlier in the season. That same year, shortly after he turned pro, he married Winifred Walzer, whom he met at a tournament in eastern Pennsylvania.

His beloved “Winnie,” who died in 1999, due to cancer, began traveling with him when he joined the pro tour in early 1955, and continued to do so until their daughters, Peggy and Amy, reached school age.

There was another big change in Palmer’s life around that time. When he was 20, while traveling on a DC-3 to an amateur golf tournament, the plane flew through a thunderstorm.

“There was a ball of fire rolling up and down the aisle,” he said. “I had no idea what it was. I thought it was all over.”

He would find out that it was an electrical phenomenon known as St. Elmo’s Fire.

“It was just static electricity,” he explained. “It released, and of course, nothing serious happened.”

That incident prompted Palmer to want to learn more about aviation. That wasn’t the first time he had made that decision. When he was about 9 years old, he had a slightly older friend who was interested in aviation.

“We collaborated in building model airplanes,” he said.

In the late thirties, another friend introduced him to acrobatics.

“He was a glider pilot,” he explained. “He came home on leave, before he went to war, and rented a Super Cub. He took me for a ride and scared the hell out of me. He was doing acrobatics and low-altitude stuff. In those days, rules weren’t like they are today. You could just do about anything you wanted; there really was no one to stop you. Of course, that created an additional interest. I really wanted to know more about what was going on when I was in an airplane.”

He vowed to learn to fly when he could afford it. When he finished the year on tour, in 1955, he began taking flying lessons, and soloed in 1956, getting his private pilot’s license that same year. He learned to fly with Babe Krinock, at Latrobe Airport (Westmorland County Airport), which is now Arnold Palmer Regional Airport.

“I started getting into flying big time,” he said.

Palmer wasn’t the first golfer to fly himself to tournaments. That distinction belongs to the late golf pioneer, Johnny Bulla, who played regularly on the PGA men’s tour in the 1930s. He’d often bring passengers along with him.

“He would take people like (Ben) Hogan and (Sam) Snead,” Palmer said. “He’d fly them to tournaments and charge them so much to go with him in the airplane.”

When Palmer first started flying to tournaments, he often ended up with passengers as well.

“It was more by accident than by design,” he said. “A lot of people would hitch a ride with me.”

In his early flying days, Palmer trained in Cessna 172s, 175s and 180s, and began chartering aircraft.

“I chartered a lot of 172s,” he said. “If it were a long trip, I would use a twin-engine like an Aero Commander.”

He bought his first plane, an Aero Commander 500, in 1961.

“I liked the thought of having a twin-engine, and it was the best buy around,” he said about that decision. “It was a repossessed airplane. It worked very well for me. I flew everywhere.”

In 1963, Palmer traded up to a Commander 560F. He acquired his first jet, a Rockwell Jet Commander, three years later, in February 1966, becoming the first athlete to own his own jet.

During that period, Darryl Brown, a former test pilot for Rockwell, served as Palmer’s chief pilot. When Brown decided to pursue other ventures, Palmer began looking for a replacement.

At the time, Charlie Johnson, a former F-105 pilot for the U.S. Air Force—and proud River Rat—was flying for Figi’s, a cheese and gourmet foods company. In 1972, Johnson’s father called him to say he had found a perfect job for him in the Wall Street Journal.

“The ad said, ‘Professional sports figure who flies his own Learjet is looking for chief pilot,'” Johnson recalled. “Dad said, ‘You know who that is, don’t you?’ I said, “I don’t have a clue; I don’t follow sports.’ It was Arnold Palmer.”

Johnson applied for the job.

“Arnold wanted to know how quickly I could go to work,” he recalled. “I said I had to clear it with my boss, John Figi. He was so proud that Arnold Palmer had stolen his pilot that he told me I could leave right away. He said, ‘That’s a badge of honor for me.'”

Johnson said he had a “nice” title, but, he was actually Palmer’s “insurance” pilot. He adds that Palmer is “probably the best natural pilot” he’s ever flown with in his life.

“Arnie just has a phenomenal set of hands,” he said. “He loves to fly. He’s very diligent about the whole thing and is an extremely good pilot.”

By the time Johnson joined him, Palmer had started flying a Learjet.

“The Jet Commander was a great airplane, but when the opportunity to get a Lear 24 came along, I took it,” Palmer said. “I flew that aircraft for nine years.”

Shortly after being hired, Johnson earned his type rating in the Learjet at FlightSafety. The process took him three days.

“Flying comes relatively easy to me,” he says, adding that Palmer was also a “very fast study.”

Johnson was soon used to Palmer’s hectic schedule, which made for some “pretty long days.” Most often, Palmer would fly in the left seat when they headed out for their destination. Johnson often took that seat on the way home.

In early 1973, Johnson would introduce Palmer to Lee Lauderback, who would eventually become Palmer’s next chief pilot. He said that back then, he sometimes needed another pilot to fly as second-in-command.

“I might need to take Arnie to a tournament sometime, drop him off and go back to pick up his wife, Winnie, or one of his children,” he said. “Or I’d go pick up another golfer to bring him in to the tournament. Regulations were a little looser then. If someone had a multiengine license at that point, you could give them a local checkout as second-in-command. I’d brief them on the airplane systems and emergency procedures and give them three landings and they could be qualified as second-in-command. I think they might’ve also had to shoot a single-engine ILS; it was something you could do locally very easily. I’d go to local FBOs, find a pilot and give him a hundred dollars. That’s how I met Lee. He was flying a Baron for a company called Lease a Plane.”

Lauderback, who began his aviation ventures as a glider pilot and did some corporate and charter work before that fortuitous meeting with Johnson, recalled that when they met, Johnson was looking for a copilot to take the Lear 24 from Orlando back to Latrobe.

“We just really hit it off,” he said. “It wasn’t long before he said, ‘Can you do it again?’ That turned in to being a part-time job of flying copilot on the Lear.”

When they ended up getting a Part 135 certificate so they could charter Palmer’s airplane out, Johnson needed a fulltime copilot.

“Instead of hiring one and moving him all around the country, I hired Lee and a pilot in Pennsylvania, Bob Agostino, who is now the director of flight operations for Learjet,” he said.

Lauderback recalled that they did quite a lot of charter work at that time.

“There was more than just moving Arnold Palmer around,” he said. “When he was in the airplane, he was in the left seat, Charlie was in the right, and I was on the jump seat. When the boss wasn’t onboard, we swapped seats. It was a good team.”

In 1975, Johnson turned over the title of chief pilot to Lauderback, after taking a position at Gates Learjet as chief of production flight test. He would later move over to Cessna Aircraft Company, eventually becoming president and COO.

“Arnie is a fast-paced, hard-charging individual,” Lauderback said. “Charlie had family pressures and the demands of trying to keep up with him. I was single, but Charlie was married, with two kids.”

Johnson acknowledged that the move was completed family related.

“Arnie was tremendous,” he said. “He was very sensitive to family situations. The problem was the nature of the job. The travel itself —being gone two hundred plus days a year—was very debilitating on a family. That was one of the reasons I’d gotten out of the Air Force—to be near my family.”

Not just aviation

Lauderback, who traveled with Palmer around the world, compared their relationship to “a well-tuned machine.”

“We met his objectives of aviation and had a lot of fun in between,” he said. “He used the airplane like you and I would use the family station wagon.”

He recalls that their partnership wasn’t the normal employer-employee relationship.

“The standard corporate position would be that the crew would stay at the airport, go check into a hotel, and be on standby when the boss wanted to go,” he said. “I never stayed around the airport. I was always with him. If he stayed at the Beverly Hills Hotel, I stayed at the Beverly Hills Hotel. If he went to a meeting, most of the time I would go with him. If he went to go play golf, I would be with him. He went out of his way to treat me pretty much as an equal, and not as an ‘I’ll-be-back-in-two-days’ type of thing.”

Lauderback admits to shying away from actually playing golf with Palmer.

“I went to college on an athletic scholarship,” he said. “I could hit a baseball at night coming at me at a hundred miles an hour, but when I put a golf ball on a stationary tee in broad daylight, when I did hit, it very seldom went where I wanted it. I was always extremely outclassed because of just being around Arnold Palmer and the other golfers.”

Lauderback said he went out of his way for many years “not” to prove he wasn’t a good golfer.

“If anyone said, ‘What’s your handicap?” my standard comment would be, ‘Golf,'” he said. “Besides that, everybody I was around wanted to play golf with Arnold Palmer. I watched all of his exhibitions and clinics and watched him play thousands of rounds of golf. But I just didn’t partake in the game myself.”

However, around 1983, Palmer called Lauderback into his workshop, not far from Lauderback’s office, and gave him a bag of clubs. Then, he instructed him to pick up some golf shoes from downstairs and make sure that the clubs and shoes were on the plane the next day, because he was going to teach him to play, once they reached their destination of Palm Desert, Calif.

“He was staying in a condominium at Ironwood Country Club,” Lauderback recalled. “I was staying maybe two rooms down. At about 6 o’clock in the morning, he pounds on my door.”

The two men were soon on the driving range.

“There was nobody there,” Lauderback said. “I’m thinking, ‘Okay. This isn’t too bad.’ Then all of a sudden, the word got out that Arnold Palmer was on the driving range. When we finished, there had to be a hundred people watching him teach me to play golf. Knowing each other so well, it’s not the humble approach; it’s the ‘Do it this way! Don’t argue with me!’ type thing.”

Lauderback said his boss worked with him, and after that, they sometimes played golf together.

“It started out that he would give me one stroke per hole,” he said. “That was about right. Then as I improved, my advantage started going away very quickly; he always kept it very competitive. He would always win me.”

Lauderback said his job wasn’t just “aviation.”

“When you’re around Arnold Palmer, who is one of the most class acts I’ve ever been around, you look and you watch and you learn,” he said. “It was the total experience of watching him do his business, and in some sense, sharing in some of those actions. He’s a very astute businessman.”

Part of that experience was realizing Palmer’s ability to identify with people.

“Arnold Palmer can go to the White House and be very comfortable talking to the president of the United States of America,” he said. “He can go in a bar in Pennsylvania and be equally comfortable talking to some coal miner, and identify with both, and be liked by both. Not everybody can do that. And he’s genuine; there’s no emphasis on trying to be something he isn’t. He truly enjoys people and he’s a very compassionate person. I think that’s one of the reasons he’s so successful with Arnie’s Army; he can identify being in trouble and being in the rough and trying to make the miracle shot. People can identify with him.”

In describing Palmer’s piloting skills, Lauderback said he was an “outstanding pilot” who was “more of a natural pilot.”

“A lot of pilots are numbers guys,” he said. “In other words, you know you’re supposed to be at this number at this time or use this number for this setting. He really wouldn’t know the number, but he would be on the number because it looked right, it felt right. As a captain, he always did his job. That made the job better; there are guys that want to fly the airplane that don’t have the ability or the tools or the knack to do it; it’s always a hassle trying to keep the guy out of trouble all the time. That wasn’t the case with Arnold Palmer. He did his job as an acting crewmember, and did it well.”

The Cessna connection

While flying with Palmer, Lauderback would become very familiar with Cessna aircraft models. Palmer’s long-term relationship with that aircraft started with Russ Meyer, now chairman emeritus of Cessna.

“He was my attorney for a long time and is a very good friend,” Palmer said. “We had been in business since 1961. We did all the aviation business together.”

After the Lear 24, Palmer began flying a Citation I, before going into a Citation II and then a Citation III.

Johnson said Palmer acquired the first production Citation III.

“When we were building the first Citation III, we would loan it to Arnie,” he said. “I’d go fly with him.”

Palmer would own two Citation IIIs, before moving on to a Citation VII.

Golf course to golf course

In the mid-eighties, after talking about it for some time, Palmer acquired a Hughes MD500E helicopter.

“That added a lot of capability to his flight department,” said Lauderback. “We could go from golf course to golf course, probably anything out within 150 miles, and beat the jet, because, with the jet ops, it would be golf course to airport, airport to airport, airport to golf course. I could pick him up in the helicopter, right there at his office on the golf course, and we could be at Jacksonville in 40 minutes. We could really get him around the country, golf course to golf course. That was perfect for helicopters, because they were always a nice place to land.”

Lauderback said he went through instructor status in helicopters, and then trained Palmer.

“Yet again, when he came onboard, he would be in the command position, and I would be riding shotgun,” he said. “It added a different dimension of aviation that we both enjoyed. That was the right helicopter; it was fast and it had lots of performance.”

Palmer said he definitely enjoyed the helicopter, but eventually sold it because he couldn’t justify the use of it.

“I wasn’t flying it enough,” he said.

Lauderback recalls that Palmer kept the helicopter for about two years after he resigned his position as chief pilot in 1990. He explains that the dynamics of his situation began changing after he got married in 1977.

“I ran into the same issues that Charlie Johnson was running into, except I stayed and ended up in a divorce situation,” he said.

He decided he’d have to change his lifestyle when his 7-year-old son Brad told him he needed to live with him. When he told Palmer he needed eight years off to raise his son, Palmer quipped, “I suppose you want pay, too.”

“Then he realized how serious I was,” Lauderback said. “It was just something I had to do. I have no regrets. Arnold and I are still close.”

Lauderback would go on to make a name for himself with Stallion 51, the world’s premier P-51 Mustang flight operation, located in Kissimmee, Fla., which he still runs.

The Citation X and Pete Luster

The same year that Lauderback resigned his position, Cessna announced it was developing the Citation X, a mid-size aircraft that today is the world’s fastest production business jet. The prototype was publicly rolled out in September 1993, and flew for the first time on December 21 that year. Certification was granted on June 3, 1996, with the first customer delivery, to Palmer, that month. Besides having the number one production airplane (serial 003), Palmer believes he was the first person to get a type in the Citation X, “other than FAA.”

Arnold Palmer answers questions about his Lear 24 while Charlie Johnson, his chief pilot, waits patiently nearby.

“I did my training in the airplane itself,” he said. “They had really not put it into the simulator or the FlightSafety program yet. I went to school for a week or so, and then I took my check ride in the airplane and did my test in the airplane.”

Johnson explained that at that time, before there was an operational simulator, you could get an LOA and convert it to the type rating. He also said Palmer had a hand in the design of the Citation X.

“Especially range of speed perimeters and interior,” Johnson said. “As a general statement, he was ‘probably’ the first non Cessna person to fly the X.”

Johnson says that presently Palmer attends FlightSafety “religiously.”

“He goes through a very accelerated course,” he said. “He spends four days; normal people spend about 10 days to two weeks. He’ll double up on the simulators and ground school. He hits it from about six or seven in the morning until seven or eight at night.”

The same year Palmer acquired his first Citation X, he was again in the market for a chief pilot, and chose another former military pilot, Pete Luster.

Luster said he went into the Air Force right from Purdue University, where he was involved in ROTC. After receiving his commission, he went to pilot training in 1966, at Del Rio, Texas. His first assignment out of pilot training was Vietnam; he flew the F-4 on a tour there, before instructing in the T-38 and then flying the F-111.

“I retired as a lieutenant colonel 20 years later,” he said. “It was a great Air Force career, but I was sitting behind a desk at that point and I wasn’t ready to do that.”

After getting out of the Air Force, he went to work for Cessna as a demonstration pilot, in 1986.

“While I was with Cessna, I got checked out in all the different varieties of Citations,” he said.

Luster was in Wichita for less than two years. One day, he gave a Citation II demo flight to a man who owned a golf resort and a company in northern Michigan. That person offered him a job, after buying the Citation II. After five and a half years in that position, Luster went on to St. Louis, to work for Siegel-Robert, another privately-owned company. For Siegel Robert, he flew a Citation I, Citation V, Citation VII, Challenger and GIV. He was there for almost four years, but left when the owner died.

“I’ve been lucky to work for good people my whole aviation career,” he said.

He began flying with Palmer right after the golfer acquired his first Citation X.

“He got it in August, and he was looking for a new pilot and I was looking for a new job,” he smiled. “We got together through our mutual friends at Cessna, primarily Russ Meyer and Charlie. They interviewed me.”

“We did all the screening on all his pilots in all Cessna airplanes,” Johnson added.

At that point, Palmer wasn’t type rated. Luster went to school immediately to be type rated, and Palmer got typed about a year later. Palmer flew that airplane for three years, before taking possession of unit 176.

“I picked it up in February 2002,” Palmer said of the aircraft he flies today.

Luster says there are some differences between Palmer’s first and second Citation Xs.

“Performance charts are a little bit better,” he said. “We get a little bit more thrust during our takeoff-and-climb phase. The controls are definitely better. They definitely improved the aileron controls. That happened at unit 150. That was much needed. We certainly noticed that.”

Luster says there’s no way an airplane can compete with the military jets he’s flown as far as “fun” is concerned, but as far as corporate jets he’s flown, the Citation X is definitely the most enjoyable.

“It has almost all of the gadgetry you could ever want, but it’s still a small enough airplane that you can get a good feel for it—and it goes real fast!” he said. “Plus it has good range and it’s very reliable.”

Palmer has put many miles on both his Citation Xs.

“I fly the Citation X from Latrobe to Europe almost every year,” he said. “I do that nonstop.”

No matter what his business is, chances are he’ll be rounding up Luster for a trip.

“If the bathroom’s far away, I fly my Citation X,” he quips.

These days

Over the years, Palmer’s aviation business has included owning a fixed base operation at Latrobe, and owning “part” of Palwaukee Municipal Airport in Chicago, including a fixed base operation at that airport. He no longer owns either of those FBOs.

“At one time we ran a charter service out of my Latrobe office,” he added.

These days, besides Luster, Palmer, now a grandfather seven times over, often flies with his fiancée Kit, and a yellow Labrador retriever named “Mulligan.” The latest of a long line of Palmer dogs, which have included golden retrievers and German shepherds, “Mulligan” seems to be content on flights.

“If I’m going somewhere for a long period of time, I take him in the airplane with me,” he said. “He goes to sleep, so I guess he enjoys it.”

As for Luster, he says he’s become accustomed to living in two cities.

“In the summer months, we base out of Latrobe, and Orlando in the winter,” he said. “I call Orlando home though. When I’m in Latrobe, I stay in one of Arnold’s houses.”

Arnold Palmer acquired a Hughes MD500E in the mid-1980s. Lee Lauderback, his chief pilot at the time, said the ability to go from golf course to golf course added a lot of capability to his flight department.

Luster smiles and says Palmer would probably have trouble denying that working for him has caused a little turmoil in former pilots’ lives, due to his demanding schedule.

“The flying has tapered off a little from what it used to be back when Charlie and Lee were with him. It would have been tough. I don’t know that I could have done any different, and I was in the military for 20 years. That can be demanding, but still, we had more of a home life than some of his early pilots must have,” he chuckles. “He was just on the go so much, and they were younger. That’s why a lot of them didn’t stay longer. He burned them out! I’m 61 years old, and my kids are gone. So I’m pretty flexible.”

Although he jokes that he is hoping things might still slow down “a little more” as time goes by, Luster says he has no complaints.

“He’s great,” he said of Palmer. “He treats me great. We’re still on the road quite a bit, but I don’t mind.”

The Palmer-Luster partnership should work well, as long as Luster’s girlfriend, Mary, continues to be flexible as well. Although the schedule might not be as demanding as it once was, Luster says there’s no way to describe a “typical” week or month.

“They’re all enough different to keep me interested,” he said.

Palmer said how often they fly these days varies month to month.

“Some months we fly probably five or six hours a week,” he said.

Luster says there’s almost always a trip or two in support of the course design company, while sponsors Palmer endorses generate others.

“Then there’s probably been an average of a golf tournament a month,” he said. “Arnold has a lot of irons in the fire.”

Luster says that although changes might come up, he’s usually able to plan his life out reasonably well.

“We have a printed schedule that’s always subject to change, but when it’s printed, probably 80 percent of what’s there really happens,” he said. “We have a little flexibility. That’s why guys like Arnold have their own airplane.”

Luster says that the cockpit situation has changed a little, regarding who’s sitting in the left seat.

“I think we split more than he used to,” he said. “He swaps with me, but it’s always his call.”

Besides yearly European flights, flying with Palmer has given Luster the chance to visit England and Scotland. A little closer to home, they fly to Hawaii almost every year.

“We go there for the Senior Skins Game and a tournament over there,” he said. “Since I’ve been with him, we’ve gone to Hawaii almost every January.”

Flights that stand out in his mind include those made to Costa Rica and Portugal, since they’re places he hadn’t been to before trips with Palmer. Those trips were related to golf course design work. He says the course design company probably has generated half their trips out of the country, but that those trips often include a golf tournament Palmer is playing in or possibly business related to other aspects of the businessman’s life. Palmer serves as a spokesperson for several companies including Rolex, Pennzoil, Invacare, GlaxoSmithKline and Administaff, Inc.

Palmer’s heroes and memorable flights

Palmer’s blessed in that his aviation heroes are in many cases also his good friends.

“Neil Armstrong is a good friend,” he said. “I think everything he’s done in the world of aviation and space is wonderful. Bob Hoover is one of the great pilots of all times. Chuck Yeager is a great pilot. I fly with Lee Lauderback all the time. I have a lot of good friends in the aviation business.”

Palmer’s made many memorable flights, including one he made as captain in a Lear 36 in 1976, in which he set a new around-the-world class record, 22,984 miles, completed in 57 hours, 25 minutes and 42 seconds.

“I had a crew that went with me,” he said. “Jim Bir, Bill Purkey, who was a flight engineer and astronomer, and Bob Serling—Rod Serling’s brother— who was a UPI reporter.”

An honorary Blue Angel and Thunderbird, Palmer has also flown most of the military aircraft, from DC-9s to F-15s and F-16s. A good friend of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Palmer also had a chance to land an aircraft on a carrier named in his honor. He landed on the “USS Eisenhower” after the commander of the Atlantic fleet asked him if he’d entertain the troops.

“I did that down in Puerto Rico,” he said.

“Pleasure” flying

In those earlier days, returning from a tournament, Palmer often viewed flying as a welcome distraction, especially if the day’s results weren’t exactly what he had hoped.

“If I had a bad tournament, concentrating on flying would take my mind off of it,” he said. “That was always a nice relief.”

These days, Palmer says the enjoyment is still as rich, but flying a jet presents different challenges.

“You have to be very alert to fly a jet aircraft,” he said. “If you fly a conventional aircraft and then go to a jet, you have to speed up your thinking process because things happen a lot faster.”

Some pilots who have gone from flying turboprops to flying jets like the Citation X have lamented the fact that their days of “pleasure flying” are gone. Palmer takes a different attitude.

“My pleasure ‘is’ flying my jet,” he says.