“Naked in Da Nang,” written by Lt. Col. Mike Jackson (USAF ret.) and Tara Dixon-Engel, is a riveting book. For a book about war, it’s surprisingly free of violence, and refreshingly free of foul language. I suspect some readers will walk away with a new perspective on Vietnam.

In part, it’s a book about a hard-fought war compromised by politicians, and some good, but misinformed Americans. Today it’s still being fought by some, albeit not on the battlefield. Only recently are Americans revisiting the Vietnam vet stereo type. I hope this book will enlighten those who still don’t get it.

The book is also about one combat pilot’s compelling, sometimes disturbing and humorous accounts of his 366 days in 1972, “in country,” often staring Death in the eye. Fortunately, Death blinked, and young Mike Jackson came home.

“Naked in Da Nang” is easy to read, but not simple. Sad at times, and provocative, it provides a healthy dose of déjà vu, and irony. In the 1960s and 1970s, young men like Mike Jackson were fighting and dying in South East Asia; others at home were defiling them when they returned, and denouncing them for seeing their duty and bravely serving.

“Naked in Da Nang” succeeds in dispelling the myth that men like Jackson, who returned, were mostly unstable flotsam created by the war. It doesn’t try to analyze the whys and the political decisions; it describes how Vietnam and those political decisions impacted Jackson’s life both there, and when he came home. It also offers a soul-searching portrait of the war, much different than this writer remembers in the media of the day.

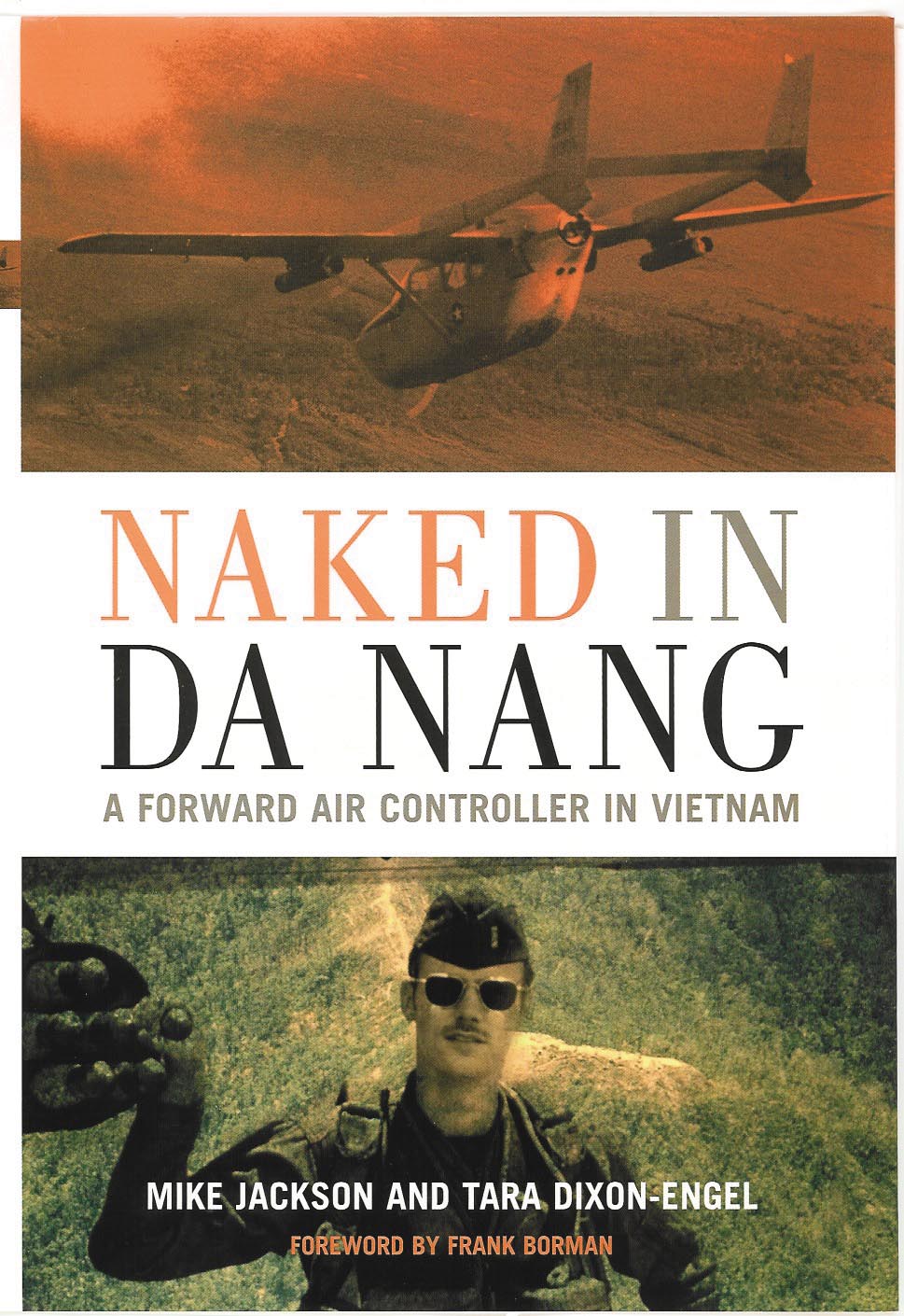

Young Lt. Jackson had a dangerous job, not that anyone in combat is immune from danger. Many of his colleagues thought anyone in his job was insane, or suicidal-maybe both. Jackson was a forward air controller, trolling the treetops, searching for an illusive enemy, and daring them to shoot at his aircraft, which they often did. Although trained as a fighter pilot in fast movers, Jackson was an O-2 pilot, flying low and slow, often within range of the enemy’s small arms fire. The O-2 is a twin-boom, twin-engine push-pull configuration of the civilian Cessna 337 Skymaster, an airplane never designed as a combat aircraft, much less as a gun platform. FACs were often saviors of grunts and downed pilots. When a ground unit encountered the enemy, the FAC would mark the target, and then call in and coordinate the air strike. When not directing air strikes, they were often flying search and rescue missions.

Jackson came home after 210 combat missions, wounded and decorated with a Distinguished Flying Cross, an Air Medal with eight oak leaf clusters, a belated Purple Heart and air medals from a grateful South Vietnam. Like the other young veterans who came home from Vietnam, he didn’t get the traditional parade afforded to our veterans from other wars. Yet, Jackson didn’t let the ghosts of Vietnam define his life.

He retired from the Air Force after 23 years, and now serves as the executive director of the NAHF. The book’s co-author, Tara Dixon-Engel, serves as director of the NAHF’s Harry B. Combs Research Center.

Naked in Da Nang, published by Zenith Press, is available in bookstores at $24.95.