By Karen Di Piazza

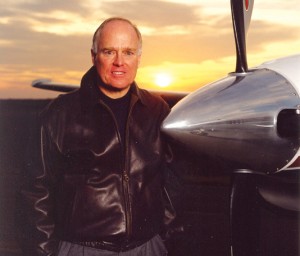

James Coyne, president of the National Aviation Transportation Association, believes that FAA audits “put the fear of God” into charter operators.

In light of the fact that general aviation, particularly that of Part 135 operations, has had more than the usual amount of incidents and accidents, so closely together in the last month or so, Airport Journals explored whether independent auditing firms have made a difference in the way Part 135 and Part 91 fleet departments dealt with safety issues. Are the majority of Part 135 operators believers in independent, on-site audits—over and above the Federal Aviation Administration’s dictums?

Not according to Jim Coyne, president of the National Aviation Transportation Association, who told Airport Journals that at the fundamental level, “the FAA audit is by far the one that strikes the fear of God into most of these guys, because only the FAA can take away their certificate.”

Gregory A. Feith, Colorado-based international aviation consultant and former National Safety Transportation Board senior air safety investigator, told Airport Journals that FAA audits may put the fear of God into people, but this perspective doesn’t serve to enhance safety.

“The fact is that the regulatory audit only determines if an operator meets the minimum safety standards implied in the regulation; it doesn’t provide an adequate gauge for determining the safety culture of a flight operation,” he said. “The pressures put on pilots, mechanics and others to conduct a flight, or how pilots will perform in high-stress situations, as well as numerous other human-factors related issues that could cause or contribute to an accident, are not addressed by FAA audits onto Part 135s.”

It’s difficult to say how the flying public views all of this, given there’s no data, but individuals Airport Journals spoke with indicated that their measuring stick for safety was based on the amount of insurance liability that a carrier had, and if they operated Wyvern-approved aircraft or had an ARG/US rating—all the better.

Kyle Sparks, a senior manager overseeing Part 135 underwriters for Atlanta-based AIG Aviation, Inc., agreed that measuring amounts of liability insurance wasn’t an indication that they had performed greater due diligence. In fact, he agreed that allowing independent auditors through the door demonstrated a “good attitude”—a willingness to improve upon the minimum FAA standards. However, he said AIG doesn’t underwrite policies based upon independent audit findings.

But no matter who you talk to, there’s no getting away from the fact that commercial Part 121 departments have a much higher safety record than that of Part 135 or Part 91 fleet departments. Per 100,000 hours flown, Part 135 has a much higher accident and incident rate. According to Boeing 777 Captain Richard Walsh, director of Colorado-based United Airlines Flight Training Center, who owns a Cessna 414 and often flies a Lear 35, “There’s a disparity between the professionalism and level of safety training with the airlines and that of 135 and 91 departments.”

He said risk analysis, cockpit resource management and human-factor principles are sorely missing from curriculums.

“UFTC’s method of an advanced quality program is integrating decision-making skills into every part of training; GA pilots need to learn that as well,” Walsh said. “They need to learn risk-air-threat management—threats you’re going to be faced with in real-world flying. And everyone is concerned about controlled flight into terrain.”

David Perdue, a former Fortune 500 corporate pilot, Part 135 pilot, senior pilot in the Air Force and certified Air Force jet mishap engine investigator, is an ATP and CFII, as well as president and CEO of iviation LLC. The Tennessee-based aviation services company performs safety analysis and on-site audits of Part 121, 135 and 91 fleet departments, and works with the government and the military. Perdue said there’s a significant difference between 121 and other FAA-regulated operators.

“It’s about professionalism and FAA requirements to begin with; 121s are required to have a flight operations manual, as is any Part 135,” he said. “Part 91 operators, though, aren’t required to have an FOM. The similarities pretty much end there between a 121 and 135. What is critical is the FOM; that’s where professionalism and safety training of 135s starts to disintegrate. The same for 91s; most of them don’t have an FOM. We need independent auditors to help 135 and 91s; the FAA doesn’t require them to employ a director of safety, have a safety program, teach CRM or CFIT—but the FAA does require 121 departments to do so.”

In fact, Perdue said that the position of director of safety is so important to the FAA regarding 121s that airlines aren’t allowed to deviate from that position unless they get permission from the FAA’s Air Transportation Division.

Feith said he agreed with Perdue and Walsh, and that independent audits take risk management to a higher level because they go beyond the regulatory compliance standard and begin to develop the risk factors, which could be identified as precursors to an accident.

“However, they too, like the FAA oversight/audit, are limited, to an extent, because if an operator knows they’re being evaluated, there’s a tendency to ‘clean up their act’ for the audit, so the ‘real’ company may not be visible to the auditor,” he warned. “This has been exemplified by numerous accidents involving commercial flight operations conducted under 121 and 135. Just because someone on paper meets a standard, it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re safe! Further, for the passengers in the back of the airplane, like passengers riding in a car, there’s a tacit level of trust in the pilot, or driver, that they’ll perform their duties at the highest skill levels to insure their safety.”

Perdue said that the FAA is considering some changes; one of them is that all pilots flying second-in-command, in any turbine aircraft, will have to become type rated in that aircraft, just as a pilot-in-command already has to be.

“The FAA is also going to insist that Part 135 operations will be required to teach CRM,” said Perdue, who is an NBAA Operations Committee member. “That worries me, though; there’s no definition of what kind of aviation background the teacher must have. People need to put their thinking caps on and ask, ‘What’s a safety program?’ With 135s and 91s, left to their own devices, if they insist on doing in-house programs—refusing to let experienced people through the door—their safety program could be a two-by-two-foot bulletin board hanging over a urinal!

“I agree with Coyne; the FAA has the power to take away a certificate holder’s license. But for the fact a 135 would only rely on ‘minimum’ FAA standards, without a safety program, it tells me they don’t understand business or safety values. They don’t see a return on investment because of safety programs being implemented; they’re poor business people who shouldn’t be in business. Frankly, that mentality shouldn’t be anywhere near passengers, whether it be a 135 or 91 operator.”

Coyne said that the FAA is just as independent and by law, 135s have to open their maintenance logs to the FAA.

“If you don’t open your logs to an independent, you don’t go to jail; if you don’t open to the FAA, you do,” he said. “The FAA is much more thorough and has much more power behind their audits. I’d say there’s a view among at least a majority of the charter operators that NATA represents that the FAA should properly inform the public that its audits are as thorough as they are. But the FAA has no economic interest in promoting its audits.”

Perdue finds it amazing that he’s seen such an incredible variation of competence accompanied by very low standards in the Part 135 and 91 sectors.

“The more we talk to companies and 135 operators, the more our eyes are opened to the lack of standardization and the somewhat cavalier attitude, which seems so pervasive in the industry, to include owners and executives,” he said. “It’s amateurish and pathetically dangerous. Further, audits should be done annually. Businesses adhere to a fiscal year, so why shouldn’t flight departments run the same way?”

Feith brings up a point regarding Perdue’s view of industry professionalism.

“This is just one of many items that require thorough investigation by the auditor; unfortunately, it’s one of the most subjective as well,” he said. “Pilots employed by Part 135 and 91 flight operations are very diverse in their background, skills, abilities, knowledge and experience. Often, the accident investigation reveals the pilot’s real experience. The Part 121 air carrier is held to a higher standard by the FAA, thus it’s assumed that there’s a higher level of discipline in the pilot segment, and a higher level of standardization, which does minimize risk.

“However, unlike the 121 air carrier, a 91 flight operation must police itself and choose to invoke and enforce a high level of discipline because there’s no outside ‘enforcer’ looking over its shoulder on a regular basis like the air carriers. So, yes, Perdue is correct, in my opinion. And they need audits.”

Perdue says the airlines are smarter, because they realize that by having safety programs and audits, ROI is very high. He said they know safety programs reduce accidents and that they save on insurance premiums.

“Most pilots want safety programs,” he said. “They know the FAA isn’t enough, but often those wants are stymied by decision makers in management—people who don’t understand the increasing complexities and demands of aviation.”

He said that when operators perform their own in-house safety evaluations, it’s “equivalent to breathing your own oxygen.”

“Carbon dioxide is poisonous,” he said. “This mentality is shortsighted—not willing to short-term spend. Or you can spend long term and pay more for ignorance.”

Perdue said that another serious problem in industry is “pilot pushing.”

“That means manipulating pilots by implied threats to their jobs, if they don’t fly when the boss orders them to, which often results in incidents, accidents and fatalities,” he warned. “If I testified as an expert witness because there was an accident that resulted in injuries or fatalities because the operator didn’t have any safety or training polices in place in its FOM, or they did, but ignored them, I’d eat them alive on the stand. It’s happened; that’s the power outside of the FAA.”

He said that officers of any aviation operation have a fiduciary responsibility for the safe operation of its aircraft.

“Independent audits identify and help manage risk,” he said. “There’s always going to be accidents, but when a family is suing you because you never tried identifying the risk, you’re in trouble. Therefore, following FAA minimums isn’t enough. For corporate 91 departments, out of about 17,000 of them, only about one-third belongs to a professional organization such as the NBAA. It shows that a small percentage is trying to become informed. The overwhelming mentality seems to be that just because someone has an ATP and 5,000 to 10,000 hours of flying time, they think they know what they’re doing. Not true! Most civilian pilots haven’t had formal training, where performance measurements determine whether they pass or fail.”

The audit block

Each auditing firm Airport Journals interviewed had different agendas and methodologies of how safety audits and safety programs could best be addressed. However, all of them agreed that solely relying on the FAA’s minimum standards was foolish.

Founded in 1991, the audit king is Wyvern Consulting, Ltd., headquartered in Palmyra, N.J., which has two subsidiaries, Wyvern Aviation Consulting, Ltd., Luton Beds, U.K. and Double Eagle, Moscow, Russia. There’s also Ohio-based Aviation Research Group/US, Inc., founded in 1995, which followed suit and began doing on-site audits in 2000.

However, there’s another kid on the block making noise. The International Business Aviation Council, founded in 1981, is a nonprofit, non-governmental association that represents and promotes interests of business aviation in international policy and regulatory venues. IBAC has taken a keen interest in audits with its International Standards-Business Aircraft Operations audit, created in 2002.

Ray Rohr, IBAC’s standards manager, told Airport Journals the IS-BAO audit would hopefully set an industry standard, “becoming a safety-program-bible” for business aviation, which the NBAA pushes hard. When asked if it was IBAC’s goal to push out Wyvern, ARG/US and other auditing firms, he explained that because there was no industry standard, where each firms’ audits were recognized by one another as being a satisfactory stamp of approval, he felt that the IS-BAO audit would be recognized by all of the industry.

John Sheehan, who serves on the NBAA’s Corporate Aviation Management Committee and is president of Professional Aviation Inc. in North Carolina as well as an IS-BAO auditor, said Wyvern, ARG/US and other independent auditing firms are important to industry, especially in regards to Part 135s.

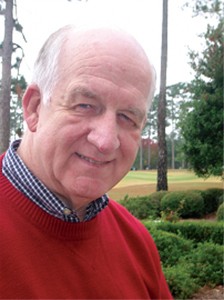

John Sheehan, president of Professional Aviation Inc. and IS-BAO auditor, believes that independent audits will always be needed for Part 91 and 135 operations.

“I’ve personally conducted about six IS-BAO audits and have overseen more than 70 corporate flight evaluations; I don’t see how anyone can say independent auditing firms aren’t valuable from a safety perspective,” said Sheehan, an ATP, former Navy pilot, flight instructor, charter and corporate pilot and flight department manager. “IS-BAO is more focused on Part 91 corporate fleets; Part 135 operations adhere to more rigorous FAA rules than do 91s. The reason for that is because 135 is for profit, flying the public. Congress wanted to make sure they had a little more oversight, but I agree it’s not enough. When a 135 carrier has passed a Wyvern or ARG/US audit, that should indicate additional scrutiny and a safer operation.”

Both Wyvern and ARG/US employ IS-BAO-accredited auditors, but the two firms are night and day in how they perform audits, give approvals or rate performance.

Walter D. Lamon founded Wyvern and serves as president and CEO. A 31-year veteran with more than 9,600 flight hours, he’s an ATP and CFII, typed in CL-601, IAI-1124, SK-76, BH-222 and BH-212. The former chair of the HAI Safety Committee is a former FAA accident prevention counselor, U.S. Marine safety officer and standardization pilot who also served in the Marine Corp Reserves in Monterey, Calif.

“We will conduct an IS-BAO audit; that’s the only type of audit that a Part 135 can pay for, but that doesn’t mean they will have a Wyvern-approved audit, because they weren’t audited to Wyvern’s safety standards,” he said.

He said 135 operators aren’t permitted to purchase a Wyvern audit.

“For purposes of integrity, we simply don’t allow it,” he said. “However, they can subscribe to the Wyvern Wingman Program.”

Lamon said that in 1980, while still in the Reserves, he started doing safety audits when he piloted helicopters for both the GIGNA Corporation and AETNA.

“In 1988, I went to work for GIGNA as its aviation safety director,” he said. “Later, I oversaw all flights as the director of corporate safety, but I realized no one was conducting safety audits. So, in 1991, I left GIGNA to startup Wyvern.”

His success hasn’t come easy. He underwent heart surgery following unsuccessful angioplasty; during that same time in 1999, owners of FlightTime Corp., an Internet charter broker that filed Chapter 7 bankruptcy in mid-2002, approached Lamon about purchasing Wyvern.

“I had no way of knowing they were headed for bankruptcy,” he said. “I wouldn’t have agreed to sell my company to them in 2000 if I had known. Nevertheless, we continued operating as usual, providing independent and unbiased safety audits, although I know there are critics who questioned if that was the case. We lost more than $100,000 to FlightTime.”

After the demise of FlightTime, Lamon purchased his company back and continued to build its reputation.

Wyvern’s philosophy is that people doing business, flying on Part 135 aircraft, are the only one’s that should be able to pay for such an audit.

“Usually, corporate Part 91 fleets and fractional providers needing supplemental lift pay for audits,” he said. “Passengers or charter air brokers also can order audits. They go through a rigorous evaluation by our experienced auditors, but we always give the operator an opportunity to fix problems. We give them an exit interview, meaning they have the opportunity to explain a situation. We’re out to help them achieve a higher level of safety, not to shut them down.”

Wyvern also performs repair station audits, FBO quality assurance reviews and needs analysis and feasibility studies, along with setting up scheduling/dispatch departments, inclusive of manuals, corporate and charter safety programs. Customers can obtain a Wyvern Desk Review that provides analysis of non-Wyvern recommended Part 135 charter operators, which zeros in on a particular flight, on a given date with a specified time for a specified aircraft.

“Those services could be a life decision,” Lamon said. “We’ve done about 1,000 audits and closed 2004, ironically, with about 135 audits. Chartered aircraft has become a staple of doing business. Knowing what exactly the carriers’ safety record is—inclusive of pilot training and pilot hours, etc.—is something no one can afford to take for granted.”

He said about 10 percent of operators fail audits because they fail to disclose incidents, accidents and problems with maintenance programs, sanctions or refuse to implement safety programs, etc. There’s no escaping the watchful eye of Wyvern; they query the FAA, NSTB and other government databases on a daily basis, he said.

“We provide the most current information on incidents, accidents and violations,” he said.

When asked to describe what qualities he looked for in hiring auditors, Lamon said they use industry professionals; a team of two or more auditors performs each audit.

“We train them to the company’s methodologies,” he said. “The profile of an auditor we’d like to see is someone who has actually performed the activities they are auditing—generally, someone who has a lot of gray hair!”

He said typically an operations auditor is an ATP and someone with thousands of relevant flight hours, who must have expertise in both management and quality assurance.

“Maintenance auditors we select are A&P rated technicians with inspection authority, and like their operations counterparts, most have exceptional management experience,” he said.

He also said that when an operator reports something, it’s Wyvern’s policy to “believe it when they see it.”

“We don’t simply report what they say; we verify everything,” he said. “Audits ensure a thorough examination in all areas of the operation.”

He also said that Wyvern has served as an expert witness in a court of law.

Operator information collected during the on-site audit is analyzed and maintained in a database. That information is accessible to subscribers through The Wyvern Report, an in-depth analysis about recommended operators, aircraft and crews.

“Importantly, safety records, insurance information and the annual audit report of each company are assessable,” Lamon said.

He said subscribers could manage their risk by obtaining all this information. Even if an operator made changes in location, aircraft or personnel a short time ago, they would know about it and they would e-mail that information to all of their subscribers.

It’s more about technology

ARG/US’ way of doing things is much different. They have performed far less audits than Wyvern; however, they’re more technology-driven instead of audit-driven. Their on-site audits are modeled after the Department of Defense Air Carrier Operations and maintenance standards inspection process.

Mark Fischer, the company’s executive vice president, said they perform audits “from customers’ points of views.”

“It’s the customer in the back of the airplane who we’re trying to please; we’re not trying to please the FAA,” he said. “It’s not a matter of pleasing; it’s that the executive sitting in the back seat expects higher standards than what the FAA demands. When people are spending $20,000 on the flight, they just want to make sure that those standards are consistently met. They expect pilots with more than 20 hours of actual flight time, which is legal as far as the FAA is concerned, but not even close to our standards.”

He said that industry needs a better method of safety inspections.

“Our goal with the on-site safety audit is not simply to rip through a carrier’s records, gathering data to be analyzed by a computer,” he said. “Nor do we duplicate the effort of the FAA, inspecting records and manuals for regulatory compliance.”

He said they keep in mind that each carrier’s mission, management style and corporate culture are unique.

“We examine each carrier for consistency in meeting its own objectives, as well as the applicable FARs and customer contract specifications,” he said.

Unlike Wyvern, ARG/US “rates” customers’ level of approval, and they allow charter outfits pay for on-site audits. However, Fischer said if they’ve consulted with them outside the scope of auditing them, they’ll refer the on-site audit to another company.

“We have three levels—silver, gold and platinum,” he said. “Silver means that ARG/US has independently resourced to other companies and has compared them to their peer groups, checking to see if they have a good safety record. That means the company has voluntarily given us all of their pilot and aircraft information. After researching all of that, and if they still have a good safety record, then they’re ready to go. At that level, there’s no fee to the operator.”

He said when you see “ARG/US gold or silver” on a website, for example, it means it’s a level based on the operator’s historical record, which is verified, not audited.

“We independently verify any background checks on the pilots and on the airplanes, and we verify the pilots’ medicals and certificate ratings,” he said. “All that is done with direct queries with the FAA. At this point, we’re compensated by the people who are chartering the aircraft; they’re purchasing that information from us.”

When asked if people could just do the leg work themselves, he said they could, but it’s very time consuming when traveling is an everyday thing.

“The charter operator only pays when we do an on-site audit,” he said.

Passing that, they’d be “platinum” rated.

“The cost varies,” he said. “Depending upon the size of the operation, and whether it’s a one-, two- or three-day process, it could be anywhere from $7,000 to $14,000. The audit is good for a two-year period.”

He said renewal cost is the same, but time in between physical audits is “filled in with updates all of the time.”

When asked if it was a conflict of interest to allow Part 135s to pay for audits, he said he didn’t see it that way, and said they were “tough” on them.

“When we do an audit, what we’re looking for is the way that company is organized, managed and how it obtained its money,” he said. “If they’re organized, managed and run in a way that has generated a good safety history, then we have audited that. In other words, they have a good record, not because they’re lucky, but because they’re well managed. That’s what we’re looking for.”

ARG/US’ most profitable center comes from subscribers paying annual subscriptions to the company’s database, which ranges from $5,000 a year to $5,000 per month, depending on how much information you need.

“We currently have about 50 subscribers; the average is $5,000 a year, but those are from giant operations to very small operations,” he said.

However, people can purchase a report for $249. These reports, updated from operators, don’t require anyone to subscribe.

“It makes sense to us, instead of individual companies having to rifle through all the paperwork every time they travel,” he said. “We’re information central, which was the intent all along. What we did is build an enormous database of anything that can go wrong in aviation. We update it every month with every record; we hired a specialist to help us develop a statistical formula to rank all these different operators and score these reports.”

He said ARG/US has been sued over this.

“But we won,” he said. “Sometimes people question us, but our data is accurate. Sometimes a company can’t accept that they don’t qualify for a rating because they don’t meet safety standards. Although a charter company can pay for an audit, they can’t ‘buy’ an audit. We have 25 different areas of evaluation; all of them must be passed. We make it clear upfront: even though you’re spending money for an audit, you might not pass it.”

Insurers take

AIG’s Sparks said it’s their responsibility to perform “due diligence regardless of what the risk is,” but different criteria will be looked at as the risk goes up.

Gregory A. Feith, Colorado-based international aviation consultant and former National Safety Transportation Board senior air safety investigator, said the FAA audit isn’t a gauge for safety; they don’t oversee human-factors training.

“First of all, AIG doesn’t quote Part 135 operators over the phone,” he said. “First, we make on-site visits with the carrier’s operation and management departments. Typically, you’ll have an aircraft liability limit that’s applicable to each aircraft for each occurrence; $25 million, $50 million or even a $100 million is certainly not out of the scope of normal. Especially if Part 91 corporate fleet departments contract out to Part 135s for supplemental lift, those are typical liability limits they expect.”

He said basing decisions on liability may not be the wisest thing for charter customers to do.

“Frankly, liability limits are all over the board; each Part 135 operator may have different liability limits per each aircraft,” he said. “For example, one 135 operator may have only $1 million worth of liability, whereas another 135 operator may have a $50 million liability limit.”

He said he understands that customers may not want to fly with someone who only carries the lowest limits possible.

“There are minimum, regulatory limits—the lowest liability coverage required in order to carry the 135 certificate,” he said. “Someone can find out what the lowest limit is per aircraft through the Department of Transportation.”

He said the higher the risk, the more exposure there is; they don’t necessarily insure each aircraft with the same level of liability.

“For example, looking at a Lear 35 with seven passenger seats, versus a 20-seat aircraft, certainly we’re going to look at that differently,” he said. “Just because we agree with something on a seven-seater, doesn’t mean we’ll agree to it on a 20-seater. The age of the aircraft, where it’s located in the country, hours on the aircraft and what the average passenger load is, etc., are factors.”

Concerning independent audits, he said “an operator could refuse to let them look at its operation.”

“If they refused, it wouldn’t go into the ‘good’ check-off box,” he said. “We look at the willingness that someone would want an audit, but then we look to see if they went beyond what the audit suggested. Did the operator take suggestions, but raise the safety bar even higher? That’s important.”

Audit naysayers and supporters

Bob Kerr, manager of Philadelphia-based Aramark’s Part 91 corporate fleet department, ascertains the level of a Part 135 charter operator’s adherence to all pertinent areas of required compliance, including maintenance and training, when his company needs extra lift. But he doesn’t believe his selected 135 operators have to be Wyvern or ARG/US rated to determine safety.

“For the value of the money spent, from our perspective, we don’t really see there’s a value in paying for independent audits,” said Kerr, who manages two Challenger aircraft and schedules at least four flights per week for company personnel. “When we do use Part 135 operators for supplemental lift, often we use Rosemore Aviation at Martin State Airport—for mid-size jets, Hawker 800s and Lear 60s—but we don’t charter the large equipment that we operate ourselves.”

Kerr bases his perceived safety expertise on “knowing the chief pilot and co-captains.”

“We’ve put our executives on their aircraft quite frequently—and they’re not Wyvern or ARG/US approved!” he says.

However, he did admit that his company pays Wyvern for its nationwide database.

“The point is, Rosemore isn’t approved with these auditing firms,” he said. “I think they’re a top-end organization; I’d put my parents on their aircraft anytime. Then you have the big names—TAG Aviation, The Air Group, Jet Aviation, etc. They all have big budgets; they can afford to pay all these auditing firms for on-site audits. They have first-class operations, but I feel sorry for a smaller charter company such as Venture Jets Inc., here in Pennsylvania, who can’t afford to jump through the hoops that Wyvern and ARG/US expect them to.”

However, Venture Jets Inc. has a platinum rating with ARG/US. The thousands of dollars spent to obtain an on-site rating such as this, for the three aircraft it has on its certificate, isn’t worth the money, according to Kerr. But ARG/US “customers” who may charter a plane from them may indeed expect to see that platinum seal.

Kerr said if his favorite 135 charter companies don’t have aircraft when he needs them, he turns to brokers to outsource for him. Pearl Bucchus, one of three owners of Executive Jet Services, also in Pennsylvania, who has provided lift for Kerr going on 14 years, agrees with him that paying Wyvern, ARG/US or any other auditing firm is not worth the money.

“Outside of providing lift for Part 91 departments, 80 percent of our business is derived from the public,” she said. “Sixty percent of business comes from corporations, which trust and rely on our company to perform due diligence—not auditing firms that all have different criteria, for a very high fee.

“We feel that our minimum standards exceed those of auditing firms. We look at a 135 operator’s insurance liability policy for starters; we know the insurance companies have really investigated them. EJS’ minimum flight hours accepted for a PIC is a total of 5,000 flight hours. Thousands of those hours must have been in multiengine aircraft, and they have to have at least 750 hours in the aircraft they are typed in, or we won’t use that operator. In other words, if we located a Lear 60 from one of our approved 135 operators, the PIC would have to have at least 750 hours in that aircraft.”

She said that the pilot SIC would have to have at least 100 hours in that type with an additional 3,500 flight hours.

“This eliminates the need for independent audits,” she said. “We receive the same annual information on all pilots, aircraft, maintintence, etc., that the 135 operator must provide its insurance carrier and the FAA. We check out each pilot’s medical certificate, etc. We service about 75 clients on a regular basis, and we don’t feel it’s necessary to pay thousands of dollars to whoever decides to label themselves as an independent auditing firm, and pay for each 135 operator to have a rating. Not when we provide due diligence that has higher standards.”

Bucchus also said that her company’s attempts in determining safety on the part of customers flying with 135 operators wasn’t based on having “actual auditing experience, looking within that particular 135’s safety polices.”

Perdue said this type of thinking is exactly what scares him.

“Again, pilot hours have little to do with actual competence,” he said. “It’s obvious that these people don’t understand aviation today; they’re closed mined and dangerous. People who investigate themselves are often too close to the forest to see the trees. Within the next couple of years, you’ll see massive changes from the FAA combating thinking such as this.”

Adam Webster, owner of AirWebster.com in Maine and Canada, is a NATA member and charter broker. He said he agreed with Perdue.

“It’s an insane notion to think that getting in-depth analysis from people who understand aviation and its complexities isn’t a valued concept,” he said. “We would always prefer seeing that 135 operators had passed an independent audit; the FAA isn’t enough. A do-it-yourself attitude met with hostility can be dangerous. It makes me ask, ‘What are they hiding?’ Granted, not all 135 operators may have had a closer look from an outside source, but if not, we require that they provide us with a lot of information or we won’t do business with them.”

Feith believes that aviation safety begins and ends with the individuals who participate in the aviation industry.

“The FAA performs free safety audits, and the information should be viewed as a positive critique rather than a negative criticism that will result in the loss of an operating certificate,” he said. “We need to utilize all the available tools to enhance safety, which includes education, training and independent audits, just to name a few.”

Coyne said, though, that many of their members have reported to him that some of these audits are very superficial.

“I’ve heard from charter members that some auditors have come in and just made sure that minimum standards are being met,” he said. “I think there’s a feeling that if there was a need for it—which I’m not convinced there is—another audit, other than the FAA, should be done by some nonprofit organization.”

NBAA

Early last month, the NBAA released a press release attempting to combat negative media reports, wherein it said, “Business aviation has an excellent safety record.”

The NBAA said that referring to three recent high-profile aviation accidents that have resulted in dramatically increased media attention on the safety of business aviation, the media had reported “misleading or inaccurate stories.” However, the NBAA did not address the three, high-profile aviation incidents in its release that did not result in fatalities.

“Unfortunately, one national news organization, ABC News, ran a story on November 29 that stated the fatal accident rate of ‘corporate aviation is 2.5 times greater than the major airlines,'” the NBAA’s release said.

The NBAA said it disagreed with ABC’s statement that the fatal accident rate for chartered aircraft is more than “50 times higher than that of the commercial airlines.”

“The basis for ABC’s statements are statistics developed by the FAA that we believe inappropriately include a broad spectrum of general aviation aircraft in their calculation, including piston-powered airplanes, turboprops, business jets, helicopters, balloons, dirigibles and gliders,” said the NBAA. “This overly broad categorization of aircraft misrepresents the accident performance of specific components within those broad categories. For corporate operations, the fatal accident rate is 0.014 per 100,000 hours, which is nearly identical to that of the scheduled air carriers, which is 0.012 per 100,000 hours.”

Feith agreed with other industry experts that said more often than not, charter pilots might have been pressured to fly when they knew better, referring to the fact that all of the fatalities were the result of Part 135 chartered aircraft.

“People need to start talking about the real issues at hand, but people don’t want to really talk about them,” Feith said. “They’re afraid, but that’s not going to improve safety.”