By Bob Shane

Sir Richard Branson talks to Steve Fossett from inside Mission Control. Fossett’s face is displayed in the background on a 10 x 12 foot plasma screen.

It was touted as “the last great aviation record,” the first solo non-stop circumnavigation of the world in an aircraft. The quest for this coveted goal brought together a successful entrepreneur, adventurer and billionaire, a professional record setter and a master exotic airplane builder. Time would show that this was a recipe for success; however, the saga that followed proved once again that the truth can be stranger than fiction, and that in aviation, there’s often no sure thing.

On March 4, 2005, the Virgin Atlantic team, headed by Sir Richard Branson; pilot Steve Fossett, who already holds 102 records in balloons, gliders, sailboats and powered airplanes; and Burt Rutan and his company Scaled Composites proved they were the right blend. The GlobalFlyer aircraft set the record for the first solo non-stop circumnavigation of the world by an aircraft in 67 hours, 1 minute and 46 seconds. Other team members vital to the success of the project included Paul Moore, the project manager; Kevin Stass, the mission control director; and Jon Karkow, the project engineer from Scaled Composites in charge of designing and building the GlobalFlyer.

The aircraft

The GlobalFlyer was designed by Burt Rutan and built by Scaled Composites. An almost all composite aircraft, it has a length of 38.7 feet, wingspan of 114 feet and a gross weight of 22,066 pounds. It’s powered by a single Williams jet engine rated at 2,300 pounds of thrust, capable of propelling the aircraft at speeds in excess of 285 mph. It has a glide ratio of 30 to 1, which fortunately didn’t have to be tested during the record-setting flight.

The launch site

Salina Municipal Airport (Kansas) was chosen for the launch of the GlobalFlyer. SLN was selected because of its central geographic location in the United States and its newly resurfaced 12,300-foot runway, which is one of the longest in North America. Originally built in 1942 as the Smoky Hill Army Air Field, it was an active base for B-17 bombers and the nation’s first operational training center for the B-29 bomber. In 1951, it was a SAC base with B-47s. The name was changed to Schilling Air Force Base in 1957. After the base closed in 1965, it became Salina Municipal Airport.

Another reason SLN was selected was that the GlobalFlyer had the overwhelming support of the entire community. Located at the airport is the K-State College of Technology and Aviation. Student volunteers provided much needed support to the GlobalFlyer project, serving as ground crew and assisting in flight planning and public relations. The school’s 300-person auditorium was transformed into Mission Control, outfitted with glass partitions, six plasma screens, 24 computers, 24 monitors, eight work stations and 10 miles of wiring.

Stan Herd, a local artist noted for his “earthwork” art, sprang into action when he heard the GlobalFlyer was coming to Salina. In a field near the airport, with a weed eater and shovel in hand, Herd created his da Vinci earthwork. Other volunteers with rototillers and gardening tools assisted him. The size of a football field, it connects man’s first understanding of the possibility of flight to the historic accomplishment of the GlobalFlyer.

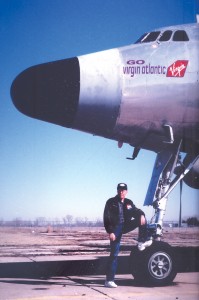

Sitting on the ramp, near the north end of the runway at the airport, is a vintage 1949 Lockheed Constellation. When its owner, Gordon Cole, found out about the GlobalFlyer coming to Salina, he quickly added nose art to the airplane, “Go Virgin Atlantic,” showing his support for the project. Cole is hoping to get a sponsor that will help get his Connie back in the air again.

This Lockheed Constellation, a long time resident of the Salina Airport, received temporary nose art showing the owner’s support for the Virgin Atlantic team. Its owner, Gordon Cole, is pictured with the Connie.

The Salina Chamber of Commerce was a big supporter. It sponsored a number of receptions for the international media. Additionally, tours of local businesses and attractions were arranged.

Finally showtime

It was thought that the flight of the GlobalFlyer would occur in early January. The first media alert was posted for January 7, which was later postponed due to unfavorable weather conditions. On February 18, the project went to code yellow with a possible launch for February 24. Unfortunately, it was back to code red for that period due to unacceptable ground winds.

Then on February 26, the project went to code green for a possible launch two days later. At that point, the wheels were finally in motion as journalists and photographers started making their way to Kansas. On Sunday, February 27, a Virgin Atlantic Boeing 747 carrying Sir Richard Branson and a contingent of international press touched down at Salina Municipal Airport.

The first press conference held in Mission Control was that evening, which was Oscar night in Hollywood. Branson boldly proclaimed, “Leonardo may win an Oscar tonight for the movie, ‘The Aviator.’ Tomorrow, Steve will prove who the real aviator is!” (By the way, DiCaprio lost out to Jamie Foxx, but fellow aviator Morgan Freeman did win one for supporting actor for “Million Dollar Baby.”)

Branson hoped that Fossett’s quest for a new world record would regenerate excitement in aviation, doing for Salina what the Wright Brothers did for Kitty Hawk, N.C.

The proposed flight for the next day was surrounded by a multitude of contingencies. The GlobalFlyer is an experimental aircraft and Fossett, with only 30 hours in the aircraft, was in essence a test pilot. The craft would be carrying full fuel, one and a half tons more fuel than the airplane had ever flown with before. Fully laden, the handling characteristics would be very different.

We would soon know if Scale got the engineering right. The takeoff would be particularly scary for Fossett. Never having flown the aircraft this heavy before, there would be the danger of a structural failure. Once airborne, turbulence could present a problem. Following the takeoff, Fossett would still be in danger for the first two hours, until enough fuel was burned off and the aircraft had reached a smooth altitude.

Steve Fossett (second from right) and his wife Peggy chat with friends, from front right, Bob Hoover, Barron Hilton, Mike Gilles and Greg Dillon, two hours prior to launch.

On February 28, at 6:47 p.m., just after sunset, a determined Steve Fossett took off in the GlobalFlyer, using more than 8,000 feet of runway. At 8 p.m., Branson stated, “I would like to thank Scaled. I know it isn’t over, but 80 percent of the biggest worrying stage is past.”

At 10 p.m., the GlobalFlyer was 55 miles north of Detroit at 38,000 feet, traveling at 310 knots. At that point in the flight there were no surprises.

Flying blind

On Tuesday, March 1, during the 8 a.m. press conference, it was revealed that the GlobalFlyer was 13 hours into its flight, near the Azores at an altitude of 45,000 feet and traveling at 330 knots. It was learned that when Fossett was over Canada, he experienced an intermittent GPS failure for a two-hour period. Without GPS, he would be flying blind. This situation could have been a showstopper. The GPS finally re-engaged and no longer was a problem.

Early that afternoon, those waiting for news at SLN were informed that the Citation chase plane had made its first intercept of the GlobalFlyer over Morocco, following it to the Atlas Mountains. Fossett had consumed three chocolate milkshakes and all was going well.

Missing fuel

A troubling development was revealed early the next morning, on Wednesday, March 2. As the GlobalFlyer was passing over China, it was determined that 2,600 pounds of fuel were missing. This revelation couldn’t have come at a more inopportune time. Fossett was getting ready to embark upon the most dangerous part of the route—the Pacific Ocean.

The folks at Mission Control began to theorize what could have happened to the missing fuel. It didn’t appear to be a leak. It was more likely a system issue such as a bent fuel line. It was determined that the fuel loss occurred during the first three hours of flight. This would suggest that the fuel could have been lost due to a venting process during the climb out. Another possibility is that the fuel was never put on to begin with; Fossett was now very much at the mercy of the winds. With winds no better than 40 knots, fuel alone would not take him back to Kansas.

The fuel burn and tailwinds were being carefully monitored. Fossett commenced a regimen of fuel conservation. This required continuous throttle adjustments, making it difficult for him to get any sleep. Fuel in the wing tanks had to be drained into the boom tanks where probes inside the tank would be able to measure it. This process enabled Mission Control to determine that fuel thought to be in the wing tanks was in fact there. Man and plane were now reaching their limits.

L to R: Richard Branson, Steve Fossett and Salina Airport Manager Timothy Rogers with the GlobalFlyer in front of the Virgin Atlantic B-747 that transported the press and Virgin Atlantic team back to New York’s JFK Airport.

As Fossett approached Japan, a decision would have to be made. Did he have enough fuel to make it to Hawaii? Fossett approached the Hawaiian Islands and another decision point, whether to land or continue onto the California coast. It was now Tuesday, March 2, and 10 p.m. at Mission Control. The GlobalFlyer had flown 18,676 miles and was now traveling at 274 knots at an altitude of 45,259 feet. It was positioned 500 miles north of Hawaii when Fossett said, “Let’s go for it.” The tailwinds were much better than expected. Fossett was becoming more confident that the record was within his grasp. He was setting his sights on Kansas.

Time to party

On Thursday, March 3, at 1:50 p.m., Steve Fossett and the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer landed safely in Salina. Fossett had endured three sleepless days and the possibility of having to ditch in the ocean, to become the first pilot to circumnavigate the globe alone, non-stop without refueling.

The official flight time was 67 hours, 1 minute and 46 seconds. The unofficial distance was 22,878 miles. At the first press briefing for the GlobalFlyer on Friday morning, Fossett was presented with a plaque from the Guinness World Records in London.

Sir Richard Branson, president and CEO of Virgin Atlantic Airways, sprays GlobalFlyer pilot Steve Fossett with champagne after his successful flight.

This was a mega-event where everyone came out a winner. Steve Fossett once again made the record books. Sir Richard Branson parlayed a $1.5 million adventure into a multimillion dollar advertising campaign for Virgin Atlantic. The students at K-State in Salina got to be a part of a world-class event, working with some of the best professionals in the aviation business. Finally, the people of Kansas were given an opportunity to confirm what we already knew, that the hospitality and can-do spirit in America’s heartland is without parallel.

When Branson, members of his team, and the international press (including this ecstatic reporter!) departed Salina aboard a Virgin Atlantic B-747-400, you can be sure it was party time all the way back to New York’s JFK Airport! While I know the aircraft wasn’t venting any fuel, I suspect that if it was venting anything, it was champagne!