By Laurie Lips

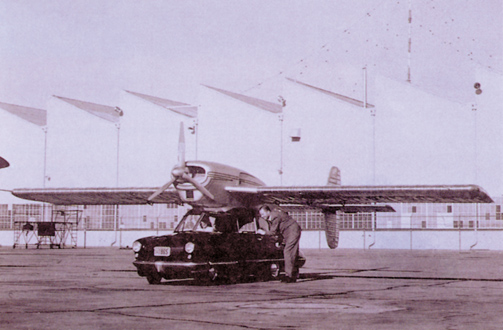

The post-World War II boom in private aviation gave birth not only to Molt Taylor’s Aerocar but also to Robert Fulton’s Airphibian and Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Company’s ConVairCar, developed by Theodore P. Hall with help the help of Henry Drewfuss.

At the age of 17, Henry Dreyfuss was designing sets for stage presentations at a Broadway motion picture theater. He also worked as an apprentice to Norman Bel Geddes, a genius of stage and industrial design.

He opened his first industrial design office in 1929. In 1930, he began designing for Bell Telephone Laboratories—an association that resulted in the design of a series of telephones. Dreyfuss was the first U.S. consultant designer whose ideas for the telephone actually saw production and reached consumers. He was best known for his revolutionary designs of such everyday household items as the Trimline phone—in 1965, placing all of the controls in the user’s hand—the Princess telephone, Westclox Big Ben and Baby Ben clocks, and the Hoover vacuum cleaner.

In 1937, Dreyfuss designed a better, more cohesive appearance in design and safety for John Deere & Company. Dreyfuss’ designers helped make the Polaroid Corporation’s Land Camera more accessible to its users, easier to operate, and less expensive, culminating in the Automatic 100 Land Camera and the Swinger (1965). Edwin Land, founder of Polaroid, liked Dreyfuss because he “didn’t know what couldn’t be done.”

In the 1950s, a circular curved thermometer, the Round, was designed for Honeywell; its low price and ability to fit most situations has made the Round one of Dreyfuss’ most successful designs. Sears Roebuck had him design the Toperator washing machine, and he designed the Flat Top refrigerator for General Electric.

Henry Dreyfuss Associates also designed the interior of the Super G Constellation aircraft for the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation and the interior of the ocean liner “Independence.”

In 1942, a prefabricated Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Company housing development in Pasadena, Calif., was done as collaboration with architect Edward Barnes. In addition to simple housing, Dreyfuss also designed interiors for the company’s airplanes.

From the point of conception to the finished product, design is a process. Because of his overriding concern for the user, Dreyfuss pioneered anthropometrics—the science of human measurements influencing industrial design. The Dreyfuss team developed “Joe” and “Josephine,” “typical” American models that were used in the design of airline seating, forklifts, power tools, and other utilitarian objects. Human factors—reach, grasp, and the many other physical and mental aspects of using an object—have become key components of the industrial design process and profession.

In 1937, Henry Dreyfuss designed a better, more cohesive appearance in design and safety for John Deere.

In the 1930s, leaving Manhattan one afternoon, Dreyfuss noted dozens of unused commuter cars in the Mott Haven yards. He returned immediately with a proposal to modify the cars for long-distance travel. The result was the “Mercury,” coordinated inside and out, from the locomotive to the coffee cups. The Mercury was a rolling test-bed for the 20th Century Limited, a completely new train.

Dreyfuss’ designs stress the user of the product. His book, “The Measure of Man,” contained extensive data on the human body and its movements. He stated in the book, “When the point of contact between the product and people becomes a point of friction, then the industrial designer has failed.”

From 1963 to 1970, he was associated with the University of California at Los Angeles. On Oct. 5, 1972, Dreyfuss, along with his wife, Doris, died of carbon monoxide poisoning in a car in the garage of their home. Many of Dreyfuss’ records and design work was donated to a collection located at the Cooper-Hewett Museum.