By Laurie Lips

The 1950s became known as the “dream” car era. With the restraints of World War II and the depression gone, flashing tailfins and big engines took the auto industry by storm; Harley Earl could put his dreams and flare for the dramatic for customized parts and accessories to work.

Harley Earl was born in Hollywood, Calif., in 1893. His father, J.W. Earl, had moved his family from Michigan to the West Coast in 1889, and had become a coach maker—customizing carriages, wagons, chariots and racing sulkies for the film industry.

Harley Earl’s father established the Earl Carriage-Works in 1908, but two years later renamed the venture Earl Automobile Works to reflect the transition from horse-drawn to motorized vehicles. His business involved customizing cars for film stars and building chariots for use in films. After attending Stanford University, Harley Earl joined his father’s business; by 1920, was designing custom auto bodies for movie stars. His first job was a $28,000 streamlined auto body for Fatty Arbuckle.

One of his more famous designs was a custom body with a real leather saddle on the roof and painted stars with the TM logo all over the vehicle built for the cowboy star Tom Mix. Legendary director Cecil B. DeMille, who was instrumental in the creation of Van Nuys Airport, also employed the younger Earl to design some of his cars. DeMille owned two Locomobiles, a Lincoln limousine, a touring Cunningham, a Cord roadster and a Model A. He believed the success of movies and automobiles went hand-in-hand and stated that the success of both reflected “the heart of motion and speed, the restless urge toward improvement and expansion, and the kinetic energy of a young, vigorous nation.” The rich could afford custom cars, and by age 30, Earl was able to boast of wining and dining with the biggest celebrities of the time.

In 1919, Cadillac’s West Coast distributor, Don Lee, purchased the business and the works were subsequently devoted entirely to car customization. Around this time, Earl devised an innovative modeling technique using clay that promoted greater sculptural expressiveness, which he used as a styling aid and which later became standard practice throughout the car industry.

Whereas in the early years of the car industry, manufacturers only had to worry about their ability to meet demand, by the early 1920s, with productivity no longer an issue, the market was growing more competitive. Earl’s Hollywood dream cars had attracted the attention of General Motors. The chairman of GM, Alfred Sloan, realized that aesthetics would play an increasingly important role, and in 1925, he lured Earl to Detroit to work on the LaSalle model, which had been introduced that year to fill the price gap between the Buick and the Cadillac. But the car had been a sales disappointment. Sloan authorized the styling of the LaSalle by removing the LaSalle from the engineering department; it was put into the hands of a new design department headed up by Earl. The resulting 1927 LaSalle was a sensation. Coupled with a 303 cubic inch 75-hp V-8 engine, it became a performance car able to average 95.3 mph, just a few miles below the Duesenberg, which had just won the Memorial Day 500 race at Indianapolis. Nearl

y 50,000 LaSalles were sold by the end of 1929, but sales never recovered from the depression years and production was discontinued after the 1940 model year.

Sloan realized that the company would profit if it could produce new cars each year that differed from the previous year’s model. This idea of annual cosmetic changes to promote stylistic obsolescence led to the creation of General Motors’ Art & Color Section in 1928. Earl became supervisor of this unprecedented styling department, which was renamed the Style Section in 1937.

During the 1930s, Earl continued to refine the LaSalle and Cadillac but one of his most famous designs of the era was the Buick “Y Job,” widely recognized as the first “concept” car. (It was called the “Y” because so many makers dubbed experimental cars as “X.”) The “Y Job” was built on a production Buick chassis modified by Charlie Chayne, then Buick’s chief engineer. It included styling of the first two-tone paint job, wrap-round windscreen and “fishtail” rear fender. Earl drove the “Y Job” as his personal car for many years. His principles of longer and lower featured disappearing headlamps, flush door handles, a power-operated convertible top that was concealed by a metal deck when down, electric windows and wheels with airplane-type air-cooled brake drums. New innovations of styling and mechanical features showed up on other Buick and Cadillac products during the ’40s and ’50s.

The 1950 LeSabre, with its jet fighter-inspired styling and flashy technical innovations—such as a rain detector that actuated the convertible roof to go up—made a hit on the auto show circuit.

GM and Earl tested new ideas on the public with a traveling Motorama that toured the U.S. from 1953 to 1961; among the ideas displayed were the prototype Corvette, the Chevrolet Nomad, and the Eldorado Brougham. Earl’s brainchild sports car, the classic 1953 Chevrolet Corvette, was designed by a handful of people in a special small studio run by Earl with the original code name of “Project Opel.” The Corvette debuted at Motorama in New York in January 1953 and was an instant hit for the Chevrolet division of GM. Many consider the Corvette Earl’s lasting legacy.

The “fabulous fifties” saw some of the most beautiful and outlandish vehicles ever made. One observer lamented, “Styling became tyrannical” and another said, “Chrome was god, and Harley Earl was its prophet.”

Oldsmobile designer Richard L. Teague once told a story of having two sets of chrome designs from which Earl could choose. By mistake both sets had been put on the same design and Earl said, “Fellas, you got it.” The car was produced with both sets of chrome overlays as the stylists shrunk in horror.

Teague said employees always called the boss Mr. Earl.

According to Teague, “He demanded respect and he got it. All us young guys were afraid of him. He kind of scared everybody half to death but he was still a terrific guy.”

At six foot four, Earl dressed colorfully, favoring light blue suits and two-tone shoes. He loved to get his long body into his low prototype cars that he designed to accommodate himself. New highways were built to accommodate the new automobiles. That meant new suburbs with drive-in theaters and drive-in restaurants that allowed patrons to remain in their cars. By the late fifties and sixties, 10 car manufacturers had been shaken down to four. The casualties included Studebaker, Nash, Kaiser-Frazer, Hudson, Packard, Willys and Crosley. The powerful influence of Earl for “lower, longer, wider” and with flashy fins beat down those who could not compete. Earl’s styling, however, became increasingly extreme culminating in the extraordinary 1959 Cadillac Eldorado with rocket-ship tail fins.

A new era was dawning, and the excesses of this era were coming to an end. The utilitarian Volkswagen Beetle started to unfold. The Earl era had ended; but it had been a good run.

Earl held his stylist job for 31 years, his staff growing from 50 to 1,100 designers. At his retirement in 1957, he reflected on his career: “My primary purpose has been to lengthen and lower the American automobile, at times in reality and always at least in appearance. Why? Because my sense of proportion tells me that oblongs are more attractive than squares, just as a ranch house is more attractive than a square, three-story flat-roofed house, or a greyhound is more graceful than an English bulldog.”

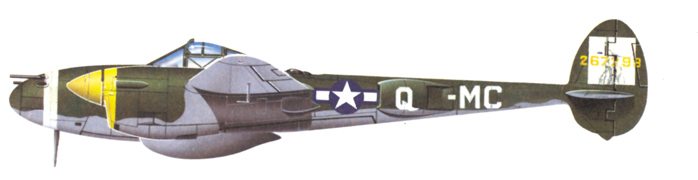

He said his most famous design, the fender tail fin on the LeSabre dream car, was inspired by an Army airplane he had seen at Selfridge Air Force Base in Mt. Clemens during the war—a P38 Lightning fighter.

“When I saw those two rudders sticking up, it gave me a postwar idea,” Earl once said. “When we introduced it, we almost started a war in the corporation.” The tailfin grew until it became a futuristic parody.

By the time of GM’s 50th anniversary in 1956, Earl had directly supervised the design of more than 35 million cars. He died April 10, 1969, at the age of 75, from a stroke.

Earl’s brand of exaggerated styling was highly influential upon the automotive industry, and his contribution is still remembered at GM in the immortal lines, “Our father who art in styling…Harley be thy name!”