By Patty Kovacevich

“People often ask me, ‘What’s the relationship between vacuum cleaners and airplanes?'” says pilot David Oreck. “My answer is, ‘Well, airplanes have to be strong, light, and dependable, and that’s how we build our vacuum cleaners!'”

Born in Duluth, Minn., 81 years ago, David Oreck’s name has been on a quality appliance of some sort in America for the past 40 years.

“Did I have a vision when I began?” he ponders. “My vision was to survive and hopefully succeed in some way.”

Oreck says he started his business from scratch.

“In the beginning I was chief cook and bottle washer, a one-man sales force,” he said. “I had one lady answering the phone in a small office in Rockefeller Plaza—a big address with a small office. I’d travel all around the country with a vacuum cleaner under each arm like Willy Loman in ‘Death of a Salesman.’ I thought, ‘Well, they’ll probably pick me up, dead, in the St. Louis airport or somewhere, laying on the floor with two vacuum cleaners beside me, and say, ‘Who the hell is this guy?'”

Oreck said things gradually got better.

“I got started that way and, bit by bit, I worked hard and fortune smiled at me, I guess,” he says with a softened humility. “Now, 41 years later, we’re an ‘overnight success.’ Actually, it’s what happens with a lot of hard work and just being tenacious. I very much agree with Winston Churchill; he said, ‘Never, never, never, never give up.’ You could call it stubborn, but the difference is: if you fail, it’s because you were stubborn; if you succeed, it’s because you were tenacious. I guess I’m tenacious.”

Oreck served for over three years in WWII after joining the Army Air Force at age 18. Following his military service, he headed to New York City.

“Fools rush in where angels fear to tread,” he reflects.

He began a job as a wholesale distributor and salesman with RCA. For the next 17 years, Oreck worked his way up to head all sales in the company, as consumers were introduced to revolutionary new products: black and white television, color television, the first automatic washer (a Bendix), the first microwave oven (a Litton), and, of course, vacuum cleaners. At the age of 40, he decided to strike out on his own.

“I had a lot of energy, a good idea, no money, and I started my own vacuum cleaner business,” he said. “It was a lonely road, because I had something that was uniquely different. It was an eight-pound upright cleaner; other vacuum cleaners then weighed three times that amount. The only big problem at the time was my competitor told the consumers, ‘Oh, Oreck’s lightweight vacuum is no good; it won’t work. It’s too light; it’s only a toy.'”

But he pushed on.

“I proceeded to sell to hotels on the basis that if it’s good in the hotel industry, the public would then realize that eight pounds did not mean that it was light in performance or light in durability,” he said. “And that’s how it all got started.”

Oreck products are not only famous for their high quality and long lifespan, but also for the service and friendliness of the over 1,500 employees and managers in over 600 stores nationwide.

“There’s such a namelessness and facelessness to business,” Oreck declares. “But people are people, and people like to communicate with other people; people like to know who they’re dealing with, whom they can count on. From the beginning, I wanted people to know I was the fellow making the statement, ‘This is my company; here’s my telephone number. If you’re not delighted with what you get, we’re going to make it right. We’ll fix it, change it, or give you your money back. We’ll even go out and wash your car if it’ll help!'”

David Oreck began his flight training in the Civilian Pilot Training program in North Dakota before Pearl Harbor.

Oreck’s company-to-customer philosophy still lives on today.

“When the customer buys something, you carry it to their car,” he said. “When the customer comes in and they have a vacuum cleaner for repair, or whatever, run out and get it and bring it in. People are impressed with the simple things. They’re impressed with people who treat them nicely—people who treat them in a caring way and who are friendly and who give a damn.”

Oreck is extremely proud his products are “Made in America.”

“No where in the world can anyone get the opportunities we have in America,” he said. “I feel keenly about supporting our country. I also believe we can control our quality by making our products here in America. We’re so dedicated that the customer is satisfied. We bend over backwards. If we ship out something that isn’t satisfactory, then we’re going to get it back. Pay me now or pay me later.

“As a result, we have dozens and dozens of checks on a product before it goes into the box. There’s no such thing as an Oreck vacuum going out and arriving, ‘Dead on Arrival.’ So, number one, we can control our quality by making it here in the United States. We don’t have to ship it from Beijing to our shores. We can turn our production lines around or move onto a different model in a matter of hours. Lower inventories, greater turnover; problems are solved with a telephone call in a matter of hours.”

Oreck said that large companies that are successful today all too frequently are arrogant and uncaring to their employees.

“That trickles to their customers,” he said. “We have a corporate culture that begins within the company and, hopefully, begins with me and flows through to the customer. We have very little turnover at Oreck. We don’t have mandatory retirement. I guess if we did, I’d be kicked out. It’s a good company. If you treat your own people well, you can reasonably expect them to treat the customer very well. Our employees know that ‘Quality is Job One,’ to steal a line from someone else. And if you need a replacement part, you don’t have to go to Timbuktu to get that part.

“Basically, America made me. I feel I owe something to America. And providing jobs to Americans for a high-quality, ‘Made in America’ product is one of my ways of giving back to the country that has made my success possible.”

Oreck’s factory is a 375,000-square-foot state-of-the-art facility in Long Beach, Miss., on the Gulf, near Biloxi, just outside the corporate offices in New Orleans. The public passes through on tours to get a first-hand look at all the products assembled at the Oreck plant.

Oreck’s many unique TV and radio commercials, which fall into their own category of classics, have also helped introduce the public to a variety of products. One of the best remembered is the singing commercial that had Oreck exclaiming, “If you want me to stop singing, call this number.” It obviously worked, because it sold lots of products, and presently remains in advertising’s Hall of Fame.

Love of aviation

Oreck’s farm in nearby Hattiesburg houses the bulk of his nine airplanes. His love of aviation goes back to his teens. He began his flight training in the Civilian Pilot Training program in North Dakota before Pearl Harbor in his desire to ferry airplanes to Europe. His first solo was in 1942, in Dickinson, N.D. Now, 60 years later, he still pilots his incredible collection of classic airplanes, which includes a Stinson Reliant SR 10J, a WACO WMF, an Aviat Husky Amphibian, an American Champion Decathlon, a Staggerwing Beech G-17S, a Beech T-34A Mentor, and a Twin Beech H-18.

During the military, Oreck was qualified as pilot, navigator and bombardier.

“It was advantageous to be a navigator then because we were short of navigators,” he commented.

The B-29, a state-of-the-art aircraft for its time, impressed Oreck.

“It could carry a bigger load, fly higher, and it was pressurized, unique for back then,” he said. “However, there was danger if we pressurized when we were over the target, because if we were hit we would have a rapid de-pressurization. So we’d pressurize only on our way to the target, then de-pressurize and put on oxygen when running bombing runs.

“The B-29 had very long range, so we were able to fly all the way from Saipan up to Japan. It also had remote-controlled guns, far advanced for back then. Unlike the B-17s and B-24s, where the gunner actually had to hold the gun in his hands, here, for the first time, the gunners would be using a device just pointed at the target and the guns operated remotely. The B-29 brought big innovations for that time.”

Oreck doesn’t have a corporate aircraft but he does have an aerobatic pilot, Frank Ryder, who flies a custom-built airplane with, of course, “Oreck” unashamedly painted on the aircraft. Ryder flies in over 10 major air shows in the country every year, almost always where the Blue Angels or the Thunderbirds fly.

The Oreck XL, part of the Frank Ryder Airshows fleet, is a classic aircraft; the Super Chipmunk was built in England in 1951. Extensively modified for air show performing, the wings were shortened by five feet overall, and ailerons were extended by 30 inches. The most notable change was replacing the original 145-hp Gypsy Major engine with a modern 295-hp Lycoming, swinging a 95-inch, three-blade propeller.

Custom built by renowned show plane builder Steve Wolf, another aircraft, the Oreck XL 2, is a powerful, unlimited class monoplane with a 550-hp Pratt & Whitney 985 engine, capable of climbing high above show center at 5,000 feet per minute. The aircraft combines technology with nostalgia from the 1930s. This one-of-a-kind, carbon fiber constructed show plane has the looks, sound and speed of a Golden Age racer, but the strength to withstand the high G forces of a rigorous aerobatic routine.

“Flying is for me more than a get-away experience; it’s a discipline,” Oreck said. “You have to pay attention, obviously. It’s always a learning experience. Whatever experience you had yesterday doesn’t count for today. Today is a totally different situation. Flying keeps you alert. There’s that old slogan: ‘There are old pilots and there are bold pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots.'”

Flying isn’t Oreck’s only pleasure. Locals can spot him daily either walking (it used to be running) or cruising to work on one of his two Harley-Davidson motorcycles, a 1975 Shovel Head Harley and a newer Heritage Harley, both in mint condition.

Adventure doesn’t stop with David Oreck. His wife Jan is an equestrian and loves to ride the horses they keep on their farm. She’s also an accomplished pilot with her own aircraft, a Super Decathlon. Of his three adult children and seven grandchildren, Oreck’s middle son Tom is also an excellent pilot, from flying gliders to his Pilatus PC-12.

Giving back

In noting courage, tenacity and the need to give back, Oreck doesn’t hesitate to express his admiration for those who serve in the military.

“When it comes to hiring somebody, if it’s someone who’s got a military background and their qualifications are equal or even almost equal to someone with no military background, I always go for the military guy,” he said. “He or she has a great advantage. First, he’s had some focus, some direction, and some discipline in his life. He’s dealt with people. He’s had to; people depended on him and he depended on others as well. He’s a team player.”

Oreck believes military service can help every young person.

“It gives direction, discipline, and an orderly mind, an orderly life,” he said. “It also gives him the guts, when faced with adversity and difficulties, not to shrink, but rather to address it and tough it out. I hear so many crybabies and whiners, it just upsets me. The world owes them a living and some of them bellyache about how their father treated them 20 years ago.

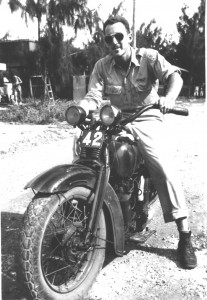

David Oreck “requisitioned” this Japanese motorcycle from a Japanese officer on the island of Saipan in the Marianas (1943).

“The military is so helpful in getting your head together and making you a responsible person. If I had my druthers, everyone would serve in the military for two or three years, or at least in community service of some sort. People suggest you’re a warmonger or some damn thing for proclaiming such, but that’s nonsense. This would help establish a core sense of discipline for our young people today.”

Oreck spends a lot of time with the youth of today. He’s in demand lecturing at more than 40 universities, including Harvard, and most recently, at the University of Georgia, where he received a standing ovation.

“They can see I’m no genius, and nobody died and left me a million so that I could get started,” he said. “My story is basically this: ‘I didn’t get started until I was 40. I did it. You can do it. Only in America could this happen.’ I also give a lot of tips, which I think are useful for someone getting going.

“It’s gratifying for me. It’s pro bono completely. I don’t let them pay me anything, including my travel. I just try to help them. I feel that I’ve helped a lot of people—a lot of young people, even a lot of businessmen—to survive, to grow. To me, that’s gratifying.”