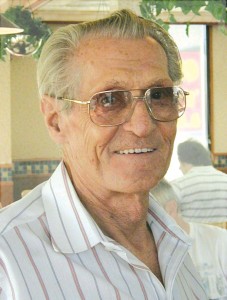

By Stan Sears

Michael Karatsonyi and his Mooney were familiar sights at Van Nuys Airport and later at nearby Whiteman Air Park

On Saturday, June 25, the 94th Aero Squadron Headquarters restaurant, in Van Nuys, Calif., was an appropriate place for a memorial service for Michael Karatsonyi, one of the finest men and best pilots who ever flew. At 4:30 p.m., on this exceptional day, a series of flyby were scheduled, one of which would be a missing man formation, the highest salute that aviation can give to honor the passing of a friend and fellow pilot.

The restaurant, located immediately adjacent to a taxi strip and the main runway of Van Nuys Airport, is named after the famous 94th “Hat in the Ring” Aero Squadron. It’s well known for its World War I aviation motif, with various military paraphernalia and photographs arranged on the walls throughout the many dining rooms.

Karatsonyi’s lovely wife, Eva, had made arrangements to have two connecting rooms plus an outside patio reserved exclusively for a luncheon for Karatsonyi’s family and friends. Well over 120 people attended the event, which was scheduled to run from 3 p.m. until 9 p.m. An excellent buffet was set up in one of the rooms, and the other had a speaker’s podium, plus a table featuring Karatsonyi’s framed portrait, along with a smaller framed collection of his military awards and a family photo album.

Reverend Zsolt Jakabffy, pastor of Grace Hungarian Reformed Church opened the ceremony with a prayer and a reading of the 23rd Psalm, which he movingly tied in with Karatsonyi’s life. The next speaker was George Renkei, one of Karatsonyi’s two sons, who reflected lovingly on his father’s life, and then invited anyone who would like to share their own thoughts about Karatsonyi to come forward and do so. Several did, then everyone moved out to the patio to eagerly await the flybys scheduled for 4:30 p.m.

The man so many turned out to honor on this was born in 1922 in Hungary, the eldest of four brothers and one sister. In 1941, a reluctant Hungary was pulled into World War II by Germany, and Karatsonyi found himself selected for service in the new Royal Hungarian Air Force. He proved to have a natural talent for flying, and quickly progressed through flight training to become a fighter ace in the Luftwaffe, flying a Messerschmitt ME-109G for the famous Puma squadron in combat against Allied aircraft. On Aug. 7, 1944, two American P-51 Mustangs shot down Karatsonyi; he bailed out of his plane with severe burns on his face and body. Incredibly, despite an arduous and painful recuperation, his courage and determination had him back in combat just two months later.

In 1949, he moved to the United States, first to St. Louis, then to Chicago, where he earned an engineering degree from the University of Illinois Institute of Technology. He became a U.S. citizen in 1954, and moved to Los Angeles in 1958.

He purchased a small glass-blowing business, which, under his knowledge and guidance, became a successful manufacturer of cathode ray tubes and high-tech quartz items for the semi-conductor, aerospace and airline industries. Karatsonyi retired from the business in 1992, but at age 70 he had hardly retired from life.

He married his lovely wife, Eva, in 1970, and became a loving father and friend to her two sons, George and Paul. Throughout his life, his warm personality, engaging smile, kindness and quick generosity won him many friends of all ages. He enjoyed a host of personal interests like gardening, cooking, classical opera, dancing and water-skiing. His greatest passion, however, was flying. In the early 1980s, Karatsonyi purchased a Mooney M-20E, a beautiful white-with-red trim, four-place, low-wing plane with a retractable tricycle landing gear. The vertical tail featured the famous Puma emblem from his Hungarian Luftwaffe Squadron 101.

“It’s my little fighter plane,” he was fond of saying.

Karatsonyi and his Mooney became familiar sights at Van Nuys Airport, where he originally kept the plane, and later at nearby Whiteman Air Park. As in all other aspects of his life, he made lasting friendships with a large number of fellow pilots who admired and respected not only his early accomplishments as a fighter pilot, but also his unselfish friendship and outstanding ability as a private pilot. Some of these men were proud to be paying their final respects as participants in the scheduled flybys.

The people gathered on the patio outside the restaurant quickly turned their eyes skyward at the roaring sound of the first plane in the scheduled flyovers—the low-flying, twin-engine B-25 Mitchell bomber named “Heavenly Body,” flown by George Hulett. Close behind and above the bomber an ME-109 Messerschmitt with Skip Holms at the controls flew a weaving pattern, adding its thunder to the sound of the bomber.

After a short interval, the runway was buzzed by a four-plane diamond formation consisting of a Beechcraft Bonanza piloted by owner Brian Dixon, a Piper Comanche flown by owner Mike Lombardo, a Lancair piloted by owner Jon Carpenter, and a Glassair flown by owner Steve Kornney.

A few other planes flew down the runway before the final, thematic flyby of a three-plane formation: owner Chris Hansing was at the controls of his Beechcraft Bonanza, owner Bob Johnson flew his Mooney Rocket, and Dan Dupre was at the controls of Karatsonyi’s Mooney, with Karatsonyi’s ashes aboard as he pulled up and out of the formation in the classic missing man maneuver.

Afterwards many of the guests intermingled, some renewing old acquaintances, some meeting for the first time, and all sharing the pathos of having lost a treasured friend.

- George Renkei, one of Karatsonyi’s two sons, reflected lovingly on his father’s life.

- George Renkei, one of Karatsonyi’s two sons, reflected lovingly on his father’s life.

- Michael Karatsonyi’s lovely wife, Eva, made arrangements to have two connecting rooms plus an outside patio reserved exclusively for a luncheon for Karatsonyi’s family and friends.