By David J. Vaughan

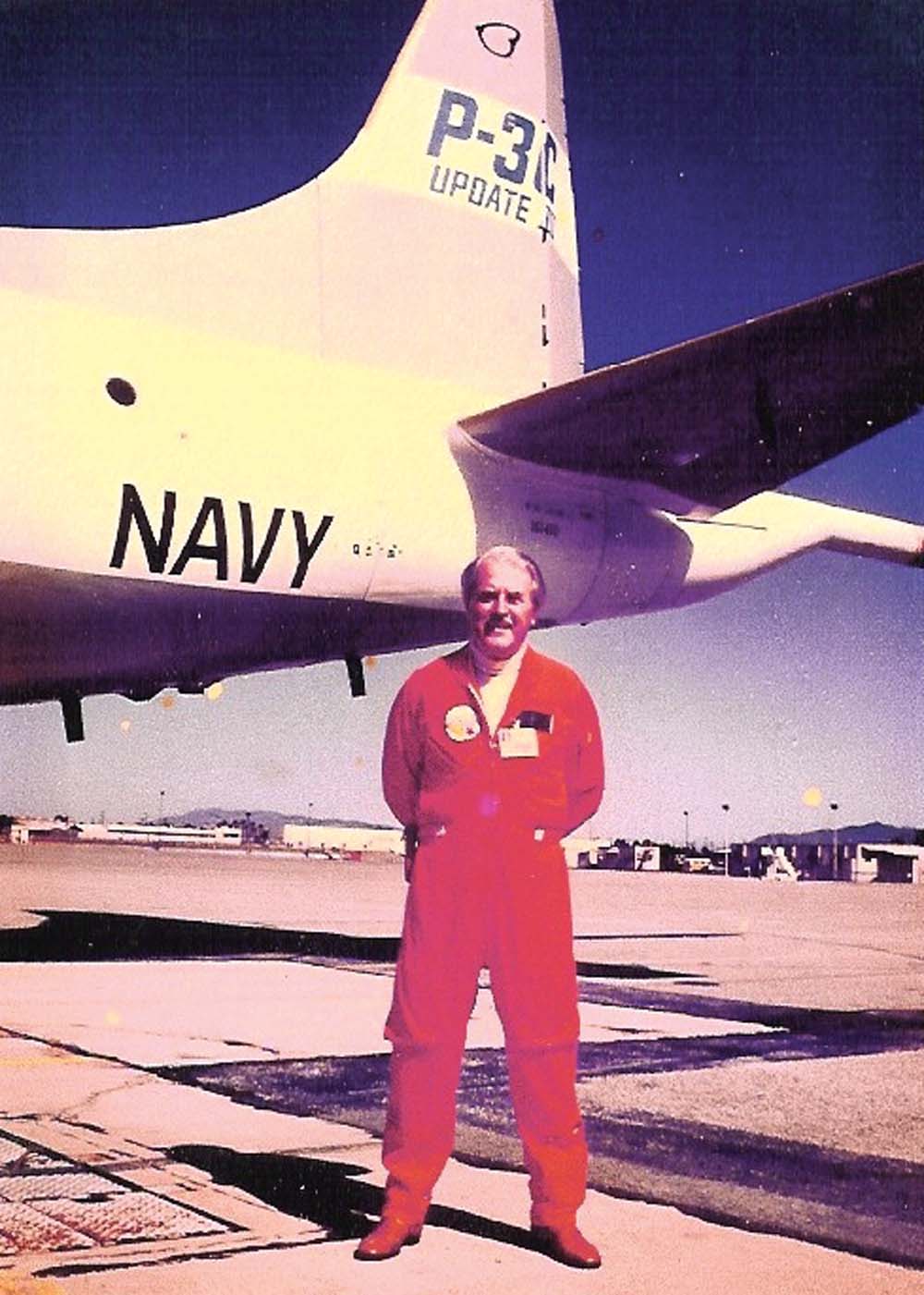

Adolph Wysocan, pictured with the Lockheed P-3 Orion, has logged many hours on this airplane as the flight test engineer.

Beginning with the Wright brothers’ first successful flight at Kitty Hawk, the contributions of subsequent pioneers in aviation and space has been routinely documented, with the emphasis highlighting the accomplishment of pilots. Names like Roscoe Turner, Wiley Post, Paul Mantz, Charles Lindbergh, Chuck Yeager, John Glenn and many others have been inscribed in aeronautical history books.

Pan American founder Juan Tripp, and legendary American Airlines president C.R. Smith may not be household names, but their accomplishments enshrined them as pioneers in aviation and business circles. But, what do we know of individuals who did not share in the publicity bestowed upon pilots, astronauts and airline founders, such as the engineers who designed and supervised the construction of historic aircraft and their components?

Recently, just such an engineer visited the Scottsdale Business Aircraft & Jet Preview. Adolph Wysocan participated in the development of some of the world’s first jet aircraft, in Germany, in the World War II era. His career, lasting over five decades, eventually spanned both sides of the Atlantic.

Wysocan, a native of Austria, was born in Vienna in 1921. He graduated with degrees in mechanical and electrical engineering from the Vienna Technical College in 1939. His interest was aviation, but at that time an aeronautical engineering degree wasn’t offered in Austria. Late in 1939, the Heinkel Aircraft Company in Rostock, Germany, on the Baltic Sea, employed him. There he assisted in designing and installing the avionics and radio systems for the prototype of the Heinkel 280, a twin-engine jet fighter, which was competing with the Messerschmitt Aircraft Company’s ME 262 to become the world’s first operationally-proven, jet-powered aircraft.

Wysocan explained that the first HE 280 airframe was completed in September 1940, but the engine wasn’t yet ready.

“The decision was made to make engine-less gliding trials to evaluate handling and flying characteristics,” he said. “A Heinkel 111 would climb to about 10,000 feet with the HE 280 airframe in tow, and the 280 would glide back to the ground. The first powered flight was eventually made on the second of April in 1941.”

Wysocan said that in January 1942, another historical aviation first occurred.

“Due to heavy icing, a test pilot was forced to use the ejector seat, which the design engineers had wisely incorporated, making it the first emergency evacuation of its kind,” he said.

He recalled that the world’s first successful aircraft exclusively built to accommodate a jet engine was the single-engine Heinkel 178.

“It was powered by the first Strahltriebwerk turbo jet engine, designed and developed by physicist Dr. Pabst von Ohain with Heinkel’s support,” he said.

Designed to be a fighter, the 435-mph HE 178 was first flown on Aug. 27, 1939, by test pilot Erich Warsitz.

“Even though the test flights of the HE 178 were very successful, the German Air Ministry demonstrated little interest in this revolutionary aircraft,” he said. “It was kept at the Heinkel plant at Rostock until the end of WWII and then destroyed.”

He said that Heinkel had earlier built the first rocket-powered plane, a fighter designated the HE 176.

“Unfortunately, as it was preparing for its first flight in March 1937, it blew up,” he said.

Not long after that misfortune, Warsitz did complete several successful flights in another prototype before the rocket-powered HE 176 project was abandoned in favor of the turbo-jet powered HE 178.

Getting back to the HE 280, Wysocan summarized the Heinkel-Messerschmitt competition.

“The 280, with its top speed of 512 mph—much faster than anything the allies had—and a service ceiling of 38,000 feet, was superior to the ME 262 in many ways,” he said. “For one thing, the ME 262 was originally built with a conventional tail wheel, which handicapped its acceleration on takeoff because the engine thrust was projected largely downward instead of aft. The HE 280 was built with a tri-cycle landing gear, from the onset, to address this thrust problem. The characteristics of jet thrust were a new challenge for the ‘propeller and piston’ engineers of my day. Because our HE 280 was superior, we were awarded an order by the German Air Ministry to immediately produce 300 HE 280 aircraft for the Luftwaffe.

“Unfortunately, being a relatively small company with limited manpower and production capabilities, it would’ve been impossible for us to meet the terms of such a large contract. Thus, it was a great disappointment to all of us at Heinkel when the contract was then transferred to the much larger Messerschmitt Company for its still unproven ME 262. We always suspected that politics also played a role in our losing the contract because Mr. Messerschmitt was well known to be on very friendly terms with high officials in the Air Ministry, particularly with General Milch, the Luftwaffe contract officer.”

Wysocan said that only eight prototypes of the HE 280 were built before production was cancelled as the result of losing the Luftwaffe contract.

In 1942, he was assigned to the production staff of the HE 219, a twin-engine piston night fighter. Recognized as a qualified aeronautical engineer, he was given sole responsibility for the design and installation of radar on the HE 219.

“Radar then was very crude by today’s standards,” he said. “It could give a bearing fairly accurately, but it had a maximum range of only about four kilometers, or two and a half miles, and the bearing and range were displayed on two separate scopes. Ours was probably as good as any existing in the world at that time, but I recall hearing that the British were reported to be making pretty good progress developing their radar.”

Wysocan said that beginning with the HE 219 in 1942, until the fall of 1944, he flew as a design and test engineer on several different Luftwaffe airplanes.

“They included the Heinkel 111, Messerschmitt 110, the ME 120, and I even made a few flights in the Junker 88,” he said. “As much of my work at that time required me to participate in test flights, I would often occupy a pilot’s seat and occasionally be allowed to fly the airplane.”

It was that exposure to piloting that encouraged him, years later in the United States, to become a pilot to supplement his engineering opportunities. But beginning in late 1944, circumstances put his engineering career on hold for nearly 11 years.

“During that time, you might say I experienced both bad and good times,” he said. “By the fall of 1944, Germany ceased virtually all airplane production because of a critical shortage of raw materials, fuel and pilots. This meant there was little or no work for engineers. Thus, my exemption from military service I had before and during the war to that point, because I was classified as an essential civilian engineer, was withdrawn.”

He said he soon found himself with a rifle in the “Wehrmacht”—the German army.

“It wasn’t long, maybe two months, and I was captured and sent to a U.S. prisoner-of-war camp in France,” he said.

Wysocan was quick to point out how glad he was that he had learned English while in high school because he was eventually selected to be an interpreter in the POW camp, making his interment much easier to accept. After nearly 16 months as a POW, he was released in March 1946 and allowed to return to his native Austria. As no aircraft manufacturing opportunities were available, he was fortunate to at least get a job with Pan American Airways at their station in Vienna overseeing airplane maintenance. Later, he also became a dispatcher. When Vienna opened its international airport in 1952, he was chosen to be the manager.

Finally, in 1955, his opportunity to return to his real love, aeronautical engineering, came. The Korean War had created a shortage of aeronautical engineers in the U.S. and Lockheed Aircraft Company’s chief engineer, Walt Jones, went off to Europe in search of qualified engineers. His itinerary took him to Vienna.

“I lost no time making myself available,” Wysocan said. “Walt Jones interviewed me and offered me a position as a senior engineer at Lockheed’s plant in Burbank, Calif. After going through immigration channels, with Lockheed’s help, I came to the U.S. in November 1955.”

Soon he became a department manager for the Data Acquisition and Data Analysis flight test organization. Beginning with Lockheed’s flagship at the time, the Constellation, his flight test responsibilities eventually included the Electra, Navy P2V and P3, the L-1011 Tri Star and the Cheyenne-56 helicopter, as well as various research airplanes. Once again, as in Germany years earlier, he participated in actual test flights, working with such well known Lockheed test pilots as Tony LeVier and Herman “Fish” Salmon, while adding nearly 500 hours to his test engineer flight time. He retired in 1987 after 32 years at Lockheed.

Summarizing his complex engineering career in aviation, Wysocan said, “I began in pre-World War II Germany, where each day presented a new challenge, as we were definitely pioneers in hitherto uncharted waters. I feel very fortunate to have had the opportunity to have had a role in the launching of the jet age and many of the technological advancements in the decades that followed.”

Wysocan was bit by the flying bug while working as a design and project engineer with the Heinkel Aircraft Company in Germany, but it was many years later when he finally had his opportunity to become a licensed pilot as a member of Lockheed’s employee flying club in Burbank. He went on to obtain his commercial single and multi-engine certificates, instrument rating and a private helicopter license. He has logged over 3,500 hours flying his own airplanes throughout both North and South American. He once ferried a Beech Baron from Los Angles to Salzburg, Austria, via Newfoundland, the Azores and Lisbon.

“That was my greatest thrill and achievement as a pilot,” he said.

Now retired from engineering and private flying, Wysocan recently moved from Burbank to Scottsdale, with his wife Theresa, where he spends time with his hobbies: cooking and browsing through old aircraft manuals and books at poolside.

Adolph Wysocan, a name you will not find in record or aviation history books, proudly represents the thousands of dedicated engineers who, from Kitty Hawk to modern space shuttles, have silently pioneered and sustained an industry.