By Greg Brown

“See where the river breaks over that wide rock?” said our guide, Donny. “We need to be careful there because the water tumbles violently on the other side, like a horizontal tornado.”

“What do you call that?” I shouted as spray filled our faces. To cap off Parents Weekend at the U.S. Air Force Academy, Jean and I were rafting the Arkansas River with our son, Austin, through Colorado’s famed Royal Gorge. Our host was Raven Rafting of Canon City.

“We call it a hole or a hydraulic,” said Donny, as we emerged unscathed on the other side. Occupants of the other boat weren’t so lucky; a man flew overboard and had to be hauled in by his companions.

“We pilots face related hazards in airplanes,” I said. “Similar horizontal vortices form downwind of mountain ridges; we call them rotors.”

“Can you see them when you’re flying?” Donny asked.

“Sometimes,” I said. “If there’s enough moisture, rotor clouds form in the eddies. Other times, lens-shaped lenticular clouds form above the rotors; they at least offer some warning. But often there’s nothing visible at all, so to avoid them you’d better know the wind speed and direction.”

“I notice you mentioned eddies. Those form in river rapids, too, and where the riverbank takes a twist,” explained Donny. “Here, I’ll show you. Right side, forward two–now!”

Shouting orders to Jean, Austin and me, Donny maneuvered our raft into a lull between the raging rapids. The boat idled calmly there with no help from us. Then he steered us sideways into one of those mean-looking horizontal rollers. There, too, the raft stood stationary; only our combined weight leaning downstream prevented it from capsizing. Our guide watched gleefully as Austin submerged to his neck on the upstream side.

“So you encounter similar challenges in airplanes?” asked Donny upon releasing us into calmer waters.

Just as water pours between rocks to threaten rafts riding river rapids, airplanes are buffeted by wind spilling through narrow passes. Here, Medano Pass slices Colorado’s 14,000-foot Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

“We do, indeed,” I replied. “In fact, we’ll face them on our flight home this afternoon.”

Intrigued, Donny asked about our route to Phoenix.

“Assuming the winds aren’t too strong, we’ll negotiate mountain passes on either side of Alamosa,” I said, comparing them to the narrow passage we’d just cleared between gigantic, jagged rocks. “Imagine rafting that passage upstream. That’s what it’s like tackling La Veta Pass through the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in the face of strong winds.”

“Sort of like rafting the river in springtime, when the water flow is much greater than now,” said Donny. “Of course, we don’t travel upstream like you do in airplanes.” Warily, he eyed the rocky channel we’d just surfed. “Nosing upriver into those rocks with the river flowing over them–now that would be wild.”

“It certainly can be,” I said. “Wind plummets over mountains just like water over those rocks. In airplanes, we use tricks like crossing ridges at a 45-degree angle to allow turning away at the last moment. Of course, it’s wisest to assess conditions before entering such uncompromising places. For example, if the winds are too strong at Alamosa, we’ll fly down the Front Range to an easier pass near Santa Fe. You probably face similar decisions when rafting.”

“That’s for sure,” Donny said. “You’d better know what lies ahead before passing the Highway 50 bridge, because beyond it, there’s no escaping the gorge for eight miles. I call it the bridge of no return.”

“One difference in airplanes is that we often fly perpendicular to the ‘current.’ Flying through canyons with a crosswind compares to traversing that double row of rocks up there crosswise,” I said.

I explained how pilots use such conditions to their benefit, like flying on the downwind side of canyons to take advantage of updrafts. As if to prove that anything achievable in airplanes is also applicable to river rafting, Donny steered us suddenly across the current through that double row of rocks.

“We call it passage ferrying,” he cried, “Right side forward three! Lean left!”

Soon, we craned our necks upward at the Royal Gorge Bridge, the highest suspension bridge in the world. Next to it hung a pendular speck.

“See those people swinging over the gorge on the Skycoaster?” said Austin. “If only the waiting line had been shorter yesterday, we could’ve done that.”

“You and Mom maybe,” I said. Swinging on a sling over a 1000-foot canyon held little attraction for me.

“Funny that you can love airplanes and not like heights,” observed Donny.

“It’s all about who’s in control,” I said. “You probably feel the same way about rafting the Royal Gorge.” Donny nodded approvingly.

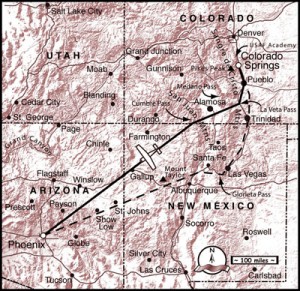

Departing the canyon downstream, the four of us went on comparing notes about our respective roles as pilots–Donny on the river and us in the skies. Just as Donny knew every rock, rapid and tourist pleaser along his stretch of the Arkansas River. We aviators had memorized our frequent aerial route from Colorado Springs to Phoenix: those daunting mountain passes, Great Sand Dunes National Park, narrow-gauge railroad tracks marking the Continental Divide and the ruins of Chaco Canyon, with their crown of ancient roads diverging like rays of the sun.

Just as Donny, our river guide, knew every rock and rapid through the Royal Gorge, we aviators had memorized the peaks and passes marking our aerial route from Colorado Springs to Phoenix.

Although we were so familiar with our respective journeys, we agreed that unpredictable factors of wind, current and weather make every passage a new and formidable adventure. In fact, for every challenge faced by one sort of pilot, the other found a parallel–it soon became a friendly competition between river and sky.

By now, the four of us coasted serenely on the final stage of our trip, pausing occasionally to swim along the way.

“You don’t get to do this in airplanes,” said Donny, grinning as he bounded into the water from our raft.

“That’s for sure,” Jean and I agreed in unison as we floated side by side on our backs.

“Well, I do,” said Austin, preparing to jump into the river from a giant rock. “I’m taking parachuting next semester.”

Author of numerous books and articles, Greg Brown is a columnist for AOPA Flight Training magazine. Read more of his tales in “Flying Carpet: The Soul of an Airplane,” available through your favorite bookstore, pilot shop, or online catalog, and visit [http://www.gregbrownflyingcarpet.com].