By Larry W. Bledsoe

“Clay Lacy’s DC-3 over Avalon Harbour.” The first flight of the famous Douglas DC-3 was made on Dec. 17, 1935. Seventy years later a commemorative flight of three DC-3s, led by Clay Lacy’s beautifully restored DC-3 in United Airlines colors.

English artist Douglas Ettridge held what was billed as his “Farewell Show” the last weekend in March at the Airtel Plaza Hotel at Van Nuys Airport. Ettridge’s art shows have been almost an annual event in California for the last 48 years. They’ve been held at the Airtel every year since 1983, except in 1994, when the British consul general asked Ettridge to stage the show at his residence. The Prince of Wales was coming to visit and the consul general thought it would be special to showcase Ettridge’s paintings there for the visit.

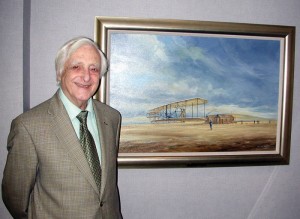

Sketching and painting is as much a part of Ettridge’s life as breathing. It’s what he lives for, and each painting has something of him in it. He “sees” himself in every scene and sometimes actually paints himself into the picture where he visualizes himself being. Take, for example, a painting he did of the Wright brothers’ aircraft at Kitty Hawk that hangs on the wall of Airtel founder Jim Dunn’s corporate office.

“That’s me in the painting,” Ettridge said, as he points to one of the people on the ground. “Well, in spirit, that is.” The fact that each painting comes alive to him, even while still in the planning stage, and that he becomes part of each one, may be one of the secrets of his success.

Ettridge said he’s been blessed that he’s been able to earn a living his entire life with his artwork.

“I’ve never had a real job,” he quipped.

During his long career, he’s done hundreds of paintings that have ended up in the private collections of many famous names in aviation, as well as in museums and corporate offices. The list of Ettridge’s collectors is a virtual who’s who of aviation, which over the years has included Gen. Jimmy Doolittle, Olive Ann Beech, Jack Conroy, Clay Lacy, Tony LeVier, Howie Keefe and Si Robin, to name a few. Other collectors include Frank Sinatra, Danny Kaye, American Airlines, Pan Am, Qantas, the San Diego Aerospace Museum and The Museum of Flight.

Ettridge, a quiet and unassuming man with a marvelous sense of humor, is every inch an Englishman, but he feels very comfortable in the States. He lived here for several years in the late 1950s and 1960s.

A prolific artist, he isn’t as well known as some in the U.S. aviation art community, because he’s known for his originals, not his prints. A couple of museums produced prints of his works for fundraising purposes. Also, he had a set of eight limited edition prints for sale at this show, but that is the extent of it so far.

Ettridge’s first show in California was in 1958, when Paul Mantz invited him to hang his paintings in his hangar and personally helped him set them up. After that show, Ettridge purchased a 1949 Ford for only $85, from the money he made from the show. Not only did he get it for a good price, but he recalls selling the car for more than he paid for it three years later.

His last showing offered 24 paintings; 14 of those are new ones done especially for this show. The featured painting was “Concorde Comes Home, New York – London, Oct. 24, 2003.” The painting depicts the last flight of the Concorde. Ettridge was delighted that he was able to be on that historic flight.

Another memorable flight is one he made in 1968 with Clay Lacy. At that time, Ettridge was living in Santa Barbara, Calif., and working for Conroy Aircraft. Jack Conroy had been working on converting DC-3s to be powered by two Rolls-Royce Dart turboprop engines. Clay Lacy flew Conroy’s Turbo Three from Santa Barbara to the Paris Air Show and back on the Great Circle Route. His crew consisted of Conroy, Herman “Fish” Salmon, Luis Salazar, Don Downie and Ettridge. The flight proved that the conversion was successful, but Ettridge said the FAA wouldn’t approve the modification as a commercial venture, saying the airframes were too old.

Ettridge has done several paintings of his favorite airplanes. He’s done many of the Ford Tri-Motor and the Spirit of St. Louis, neither of which appeared in this show. He also loves the British Spitfire. Their role in World War II caused him to recall, “It was the Spitfire and Hurricane that saved England.”

He was 13 during the Battle of Britain, living in Surrey County. He remembers large formations of German He-111 bombers flying over, escorted by Me-109s and twin-engine Me-110 fighters. He acted as a spotter and told his classmates to take cover whenever he spotted German aircraft. He remembers seeing large formations later in the war, some with more than a thousand planes.

As a child, Ettridge constantly sketched the planes he saw. His grandmother always encouraged him and ended up with most of those sketches. Unfortunately, when she died the sketches were buried with her.

He left school when he was 16, and went to work for a commercial artist, while attending night school for three years. For a time, he was apprenticed to his uncle in his advertising firm. Having trained and worked as an illustrator, he can sketch and paint anything. The first time he sketched a nude female model in one of his night classes, he took quick shy glances at the model, instead of looking at the subject while letting his hand sketch what his eyes saw. That made it difficult for him to complete the sketch accurately. When he went home that night and showed his parents his sketches, his mother was upset, but his father jokingly said that he, too, might want to take the sketching class.

Although Ettridge isn’t confined to one field, he knows and loves balloons and airplanes. He describes himself as a realist and an illustrator/artist with a preference for aviation and modestly turns aside references to being a great artist. His talent, he says, was polished by his apprenticeship, night school, and his observations of real life and great artists whose work he admired.

The Boeing Model 307 Stratoliner was the first fully pressurized airliner to enter service. TWA purchased five for their transcontinental route. Ettridge’s “Westward, Eastbound, 1939 Boeing Stratoliner,” shows one of TWA’s airliners over the Manhattan sky

In Ettridge’s opinion, Joseph Mallord Turner is the best painter of clouds. Although Turner and John Constable have greatly influenced his work, as well as American artist R.G. Smith, Ettridge feels Frank Wootton is the finest aviation artist of all.

Ettridge does all his paintings on quality flax canvas and still stretches his own canvases. A traditionalist, he says he doesn’t have much appreciation for “art” that isn’t realistic, but he doesn’t go for photo-realism.

To prepare for a painting, Ettridge does several sketches to get a feel for the composition. Sometimes he does small watercolors of certain details that will go into the painting in order to see how colors will fit in with the overall composition. In every sketch and painting, he notes the direction of the wind, the time of day and the weather to come. Even when he’s thinking of future paintings, he makes the same notes, along with the subject to be depicted and other ideas about the painting. This helps him to recall and to focus on small details.

When he does a commissioned painting, he develops the final concept from talking with the person making the request and from the photos provided, though he never simply copies an image as it is in a photograph.

Each painting requires more research than most people imagine. Ettridge says the clouds and atmosphere are an important part of the story. The clouds tell of the coming weather. Again, he always notes the time of day, the wind direction and the type of clouds to be depicted, regardless of whether the background is going to be an airscape or landscape. And he researches the location for that period of time being depicted, in order to include only those landmarks that were there at the time, and, of course, the primary subject to be depicted.

Models help him understand how the aircraft looks from the perspective he wants to use, and he sometimes refers to photographs for reference. He says a painting is of an entire scene, not just the aircraft being depicted, and that it’s important to get all the details right.

In 1924, Hollywood stuntmen Ronald MacDougall, Ken Nichols and William Matlock formed a stunt pilots’ union they called “The Black Cats.” Ten more would eventually join the organization, making it the “Thirteen Black Cats.”

Ettridge has used acrylics since he was introduced to them 25 years ago. He thinks it’s a wonderful medium to work with and immediately saw the possibilities it had over oils. For one thing, he could finish the background one day and the paint would be dry enough to start painting the aircraft the next day. He didn’t have to paint around where the aircraft was going to be, but could complete the background and paint the plane over it.

“That gives continuity to the background,” he said.

Ettridge likes to encourage young artists. He recalled older people doing the same for him and making helpful suggestions on how to improve his work. He also said it’s very important to have a total visual awareness of the plane being depicted. Take lots of notes and sketches. Also, don’t forget to take a camera.

Although this show was billed as his “Farewell Show,” Ettridge isn’t going to hang up his paintbrushes, because he continues to be happy when he’s sketching and working at his easel. Now, he’s looking forward to traveling with his wife and painting what he wants, when he wants, for his own pleasure, without having the pressure of doing something needed for another show. Wherever he goes, he’ll have his easel and sketchpad with him.

But is this really his last show? When asked, he just smiled, but the twinkle in his eyes said, “We’ll see.”

To inquire about Douglas Ettridge paintings, email him at ettridgeart@tiscali.co.uk.

- “Glenn Curtiss wins air race attaining 47 mph” must have been the headline following the world’s first air race depicted in “First Air Meet at Rheims, France.”

- Author Larry Bledsoe and Douglas Ettridge discuss some of his paintings. Larry and his wife, Jane, met with Douglas and Joyce Ettridge a few days before the show began.

- Never in history has such a vast armada of ships, men and planes gathered as they did for the assault on the beaches of Normandy in WWII. “P-51 Mustangs over Omaha Beach, D-Day 1944” shows only one small snapshot of the action that day.

- Jim Dunn and Douglas Ettridge with the feature painting of the show, “Concorde Comes Home, New York.”

- Imperial Airways carried passengers and mail in Empire class flying boats such as the Shorts S23s. “Sunset Arrival, Luxor, Egypt, 1935” depicts the S23 Canopus making an evening landing en route.

- Artist Douglas Ettridge and his wife, Joyce.

- Imperial Airways carried passengers and mail in Empire class flying boats such as the Shorts S23s. “Sunset Arrival, Luxor, Egypt, 1935” depicts the S23 Canopus making an evening landing en route.