By Robert Louis DalColletto

The 56th Fighter Group, nicknamed “Zemke’s Wolfpack” after its commander, Hubert “Hub” Zemke, was one of the most famous and successful fighter groups in World War II, scoring more aerial victories over Europe than any other. The 56th Fighter Group was the first group to fly the P-47 and the only 8th Air Force group to fly P-47s throughout the war. They were credited with 665 aerial victories and 311 ground claims. With an incredible kill ratio of 8 to 1, Zemke’s Wolfpack was a true leader of the pack.

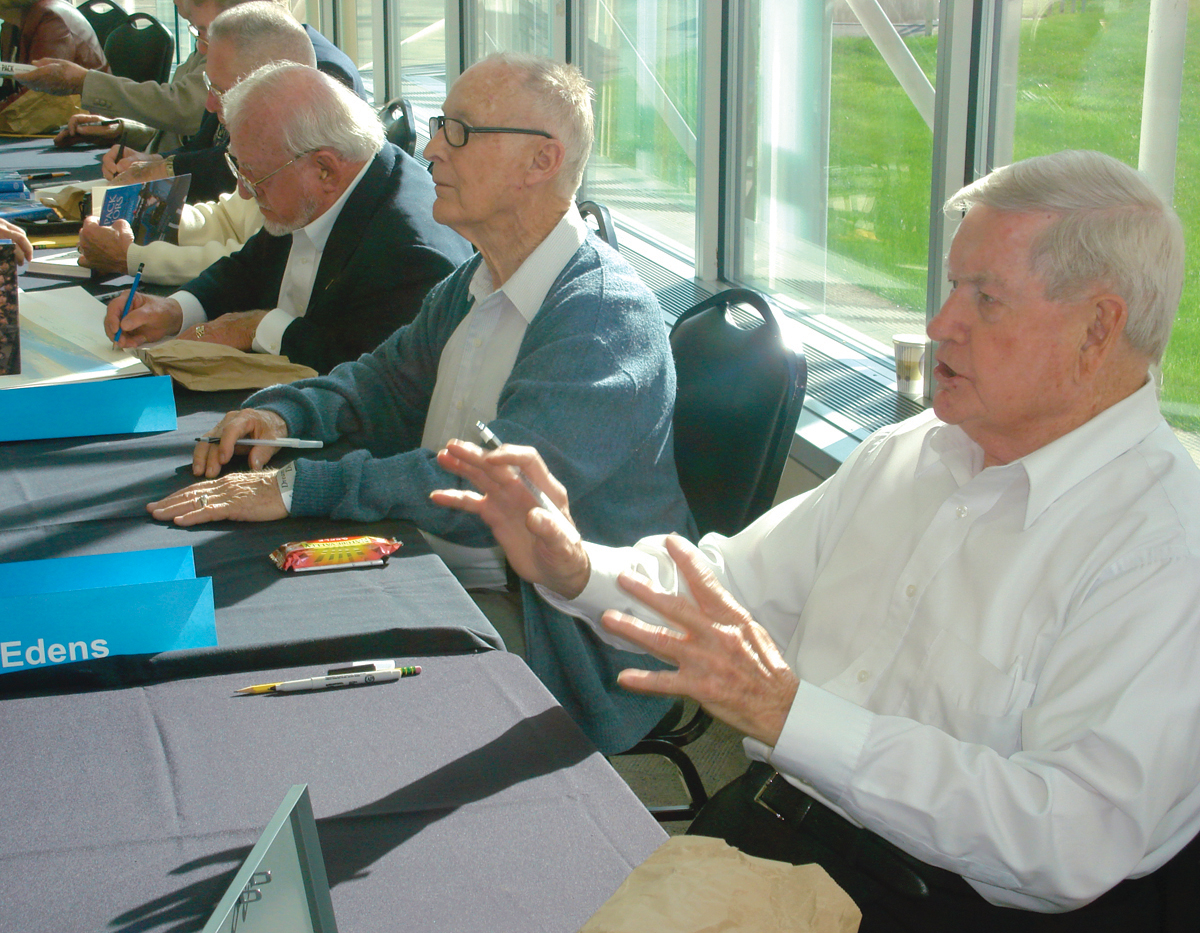

L to R: Freddy Fredrickson, Robert Rankin, Wally Groce and Billy Edens enjoy a day dedicated to “Zemke’s Wolfpack” at The Museum of Flight.

In a series of interviews that started with their appearance at the Museum of Flight in Seattle on April 22, 2006, four survivors of Zemke’s Wolfpack—Harold “Bunny” Comstock, Billy G. Edens, Russell “Freddy” Fredrickson and Walter Groce—each gave chilling accounts of their time at war. From intense dogfights and strafing missions to death-defying escapes, these courageous pilots resembled the P-47s they flew: rugged and unrelenting.

As for Comstock, Edens, Groce and Fredrickson, sitting next to each other at the Museum of Flight, you could feel the quiet regard they had for one another, their commitment to the fight and to each other, unwavering still. Their sheer determination to succeed and survive—at times against horrific odds—remains inspirational to this day.

Harold Elwood “Bunny” Comstock (5 victories)

Born in Fresno, Calif., on Dec. 20, 1920, Harold Elwood “Bunny” Comstock loved building model airplanes and being a Boy Scout. As a young man, he had a good job making 50 cents an hour as a Butane Service Station operator. But his dream was to fly.

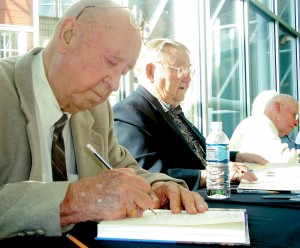

L to R: Bunny Comstock, Frank Klibbe and Freddy Fredrickson participate in a busy autograph session at The Museum of Flight.

Comstock entered Army Air Force primary training on Oct. 9, 1941, and got his wings and commission as a second lieutenant on July 2, 1942. He was assigned to the 63rd Fighter Squadron, 56th Fighter Group at Mitchell Field, N.Y. The group was sent to England in December 1942 and began operations out of King’s Cliffe and a Royal Air Force station in Wittering.

While testing new antennas on the P-47 Thunderbolt, Comstock was one of the first men to attain the theoretical realm of “compressibility.” While practicing a horizontal speed run from 35,000 feet up to 49,600 feet, he put his plane into a near vertical dive and couldn’t pull out because the stick was locked solid. It was a near disastrous situation, but fortunately he encountered denser air and recovered.

This is explained by the “Mach factor,” the ratio of an aircraft’s speed to the velocity of sound, which varies with altitude but is around 725 mph at sea level. The faster an aircraft goes, the more air builds up in the front to a point where it’s forced against the wing and tail control surfaces. The P-47 could attain remarkable speeds in a dive, often exceeding 500 mph, and as Comstock found out, it could hold up under extreme conditions.

Comstock scored his first combat victory on Aug. 17, 1943, downing a Messerschmitt Me 109 near Ans, Belgium. On October 4, he destroyed an Me 110 over Bruhl, Germany. November 26 was a busy day; he shot down an Me 110 and damaged a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 and Me 110. He was credited with an Fw 109 probable and two damaged 190s before completion of his first combat tour in early 1944.

Captain Harold E. “Bunny” Comstock receives a medal in 1943. At his right is Dave Schilling (holding a box). Comstock served 30 months and two tours; he finished his second tour as the commanding officer of the 63rd Fighter Squadron, with 136 missions.

Comstock recalled an “ordinary” victory over an Me 110, with a rear gunner.

“He was turning to the right and I slipped way out to the left and came back and hit him in the cockpit,” he said. “His rear gunner was trying to hit me and couldn’t get the gun around. As soon as I hit him, the wings stayed down, and he went straight down. I followed him for awhile, and then I figured that was enough for one day.”

A well-respected, natural leader, Comstock was promoted to major on Sept. 17, 1944, and given command of the 63rd FS for a second tour, where he completed a staggering total of 136 missions. However, the next day, on September 18, he was commander of the “ill-fated” mission into Arnheim, Holland, code marked “Market-Garden.”

Later, Comstock would recall that he tried to refuse the mission but was told to go at all costs.

“The OP order read that we couldn’t shoot at anything until it shot at us—an impractical and impossible order,” he said. “And it was extremely costly. Wingman David Kling was our first loss, but survived. I aborted the mission when too many aircraft were being hit.”

By noon of that same day, the situation in Arnheim was in an advanced state of deterioration. The 8th Air Force P-47 group was engaged in flak suppression. However, the Germans had recovered and were much more effective. The 56th FG, which provided 39 Thunderbolts, lost 17 of them, with a dozen damaged. Two pilots became POWs and four were killed. It was the worst day of the war for Zemke’s Wolfpack.

On Dec. 23, 1944, Comstock became an ace, destroying a pair of Fw 190s and damaging two others, Southwest of Bonn, Germany. That day the 63rd FS destroyed 12 Fw 190s.

During WWII, Comstock destroyed five enemy aircraft in the air and two on the ground; he was also credited with one probable and seven damaged, in addition to 22 locomotives. His success was making sure to “get behind them.”

He clearly prefers telling mischievous stories over real war stories, especially about the things he and his buddies got into returning from their first tour. That’s when his humorous personality shines.

“One time, a bunch of us were in a movie theater—my wife Barbara and I, Joe Egan (an ace with five victories for the 63rd FS), Dave Schilling (22.5 victories), and Billy Hovde (12 victories for 358th FS),” he recalled. “We were watching a newsreel of an Fw 190; its left wing is blown off and it crashes and burns. Right in the middle of the packed theater, Billy Hovde stands up and says, ‘I shot down that son of a bitch!'”

One story that seemed very endearing to Comstock was about a waffle iron. Electric appliances were hard to come by, but his father managed to get him a waffle iron following his first tour, and he was determined to bring it with him on his second. It soon became the “infamous” waffle iron and no doubt brought a little bit of home to hundreds of his fellow men overseas.

After completing his second combat tour, with a total of 30 months in the European theater, Major Comstock was sent back to the states, where he commanded the 10th FS, 50th FG. Over a four-and-a-half-year period, Barbara Comstock gave birth to three sons who would all grow up to serve in the military.

Comstock commanded the 389th Fighter Bomber Squadron, in F-86s, and later commanded the 481st in Kunsan, South Korea, flying F-100s.

“We stood nuclear alert in Kunsan, with the target in Russia,” Comstock said.

He completed two tours in Vietnam, commanding the 481st Tactical Fighter Squadron, 27th Fighter Wing, flying F-100s. During his second tour, he led a C-130 command and control unit, for a total of 170 missions. Upon completion of his tour, Comstock earned a BA in political science.

Harold “Bunny” Comstock served 30 years of active duty and retired as a colonel on Sept. 30, 1971. He received two Legion of Merit awards, the Distinguished Flying Cross with 6 Oak Leaf Clusters, the Purple Heart and the Air Medal with 16 OLCs.

The Comstocks have been married 63 years. His interests include his eight grandchildren and a great granddaughter, as well as politics.

Summing up his advice on being an effective leader, he says, “Never ask your men to do anything you wouldn’t do, and you do it first.”

Billy G. Edens (7 victories)

Traveling all the way from Chattanooga, Tenn., Bill Edens, 83, spends a day recounting amazing stories, greeting admirers and signing autographs.

Billy G. Edens, born on Jan. 21, 1923, in Cassbille, Mo., was 6 weeks old when his family moved to Tyronza, Ark. After graduating from high school on June 1, 1942, Edens joined the Army Air Corp on June 27, 1942. Once he finished primary and basic glider training, he completed advanced glider training on March 1, 1943.

He was accepted as an aviation cadet on May 3, and did all his flight training in Alabama. After completing P-47 training, Edens received his wings and commission on Nov. 3, 1943.

“I had read about the 56th Fighter Group and all their aces in Reader’s Digest, so I signed up with them,” he said.

In April 1944, Second Lieutenant Edens was assigned to the 62nd Fighter Squadron of the 56th FG, flying P-47s out of Boxted, England. Edens’ aggressiveness and natural ability earned him the title of ace in less than a month, as he totaled seven victories between June 8 and July 7, 1944. On June 8, while defending flight leader Mark Moseley, Edens destroyed two Me 109s and an Fw 190 to earn a triple in one day.

“I was just shooting them off his tail,” Edens explained.

On July 5, he shot down an Fw 190 that burst into flames, and two days later, Edens became an ace when he destroyed three Junkers Ju 52 transports. The 62nd FS destroyed 10 of the 12 Ju 52s they encountered that day.

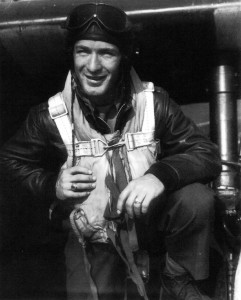

Second Lieutenant Billy G. Edens, at Boxted Air Base in England in May 1944, was one of only a few pilots from the 56th Fighter Group to become an ace as a second lieutenant.

“My tail hit his tail,” Edens described of one of his victories. “I was on top of him, so I just pulled back on my stick real hard and my ‘Jug’ just smashed him and he crashed and burst into flames.”

On September 10, during his 89th and final mission, Edens was shot down—for the fourth time—while strafing the Seligenstadt Airdrome. But this time he was captured and became a POW at Stalag Luft I in Barth, Germany. A month later, Col. Zemke ended up at the same prison camp and found himself senior allied officer, responsible for 7,000 allied prisoners. Francis Gabreski (28 victories) was already there and a compound commander.

Edens recalled a mesmerizing tale of what he said “wasn’t a happy experience” but was exciting.

“One day, this Russian second lieutenant captured the whole prison camp and said we’d been liberated,” he said.

Later, Zemke ordered Americans not to leave, fearing they would get shot if they went into town. But Edens and two others didn’t hear Zemke’s orders, because they had already caught a ride on a Russian truck. Several hours later, in broad daylight, they were unknowingly walking towards Berlin.

“Some Russian soldiers captured us,” he recalled. “I told them ‘Americonski.’ But they didn’t listen. Instead, they made me commander of 200 Russian soldiers. We were told to clear the houses in Berlin. The Russians wanted all knives and guns in the street. If they found anyone shooting from houses, everybody in that house would get killed.”

After a week, all the infantry officers, including Edens, were sent back to Russia.

“We started walking, thousands of us, with guards, for three days and nights, with almost nothing to eat,” he said. “Then they put us on a boxcar and locked us inside with two barrels, one filled with water, the other to use the bathroom.”

Four days later, Edens arrived east of Moscow in international camp #1, where armed Ukrainian guards were positioned in towers.

“We were there three and a half months,” he recalled. “I had a little book and wrote down the names and addresses of 97 Americans, in case we ever got out of there.”

One night, a Russian told Edens there was “going to be a break.” That night, thousands of prisoners rushed the fence, pushing it down with sheer bodily force.

“The Ukrainian guards were shooting hundreds of people, as fast as they could,” he said. “I managed to get out and ran until I couldn’t run anymore. I was less than a hundred pounds then. Only three of us Americans got out. We never knew what happened to the others.”

Accompanying Edens was Michael Quirk (a 12-victory ace with the 56th FG) and John Biggs.

“It took us five to six weeks to walk from Russia back to Berlin,” Edens remembered. “Some villagers gave us something you wouldn’t feed your pig, but we ate anything to survive.”

When they arrived in Berlin, the three men found some American soldiers who put them into prison. After three days, they were identified and sent to Southern England where they boarded a Navy ship.

“We got some food and started drinking straight 180 proof grain alcohol,” he said. “But as daylight came, I couldn’t see any land. Some guy said, ‘We’re on our way to America,’ and I said, ‘I’ll be darned.'”

Twenty-one days later, the ship arrived in Virginia where Navy SPs were waiting and put the three men into another prison. After three days, Edens, Quirk and Biggs were identified and released.

After Edens received his back pay and was granted leave, he finally returned home and married Kitty, a young woman he’d known since the first grade. The Edens have been married 60 years.

But it wasn’t long before Edens found himself in another death-defying situation. On April 28, 1950, he survived a crash-landing with a fire in an F-84 at Bergstrom AFB in Texas.

“The engine quit on takeoff and I ended up in the hospital for four and a half months with two crushed vertebrae and burns on my head, face, hands and right side,” he recollected.

When he got out, he was soon flying F-84s again. In the fall of 1950, Edens went to Korea on “temporary duty.” He didn’t return for almost a year.

Jan. 23, 1951 was a historic day for the 27th Fighter Escort Wing, 522nd FS. Group commander Lt. Col. Donald Blakeslee led 33 F-84E Thunderjets on a strafing mission at the Yalu River, between North Korea and Manchuria. But the “real” mission that day was to entice Russian MiG-15s to get airborne and into a dogfight. Dozens of MiGs took off from the Antung airstrip in Manchuria, commencing the largest jet air battle in history.

After a brief but intense dogfight, most of the 27th FEW, including Blakeslee, began heading back to the rendezvous point.

“After they left, it was just Jake Kratt, Bill Slaughter and I,” Edens recalled. “Then one of ’em said, ‘I’m out of ammo,’ and he left. Then the other said, ‘I’m low on fuel,’ and he left.”

Edens, all alone, got on the radio.

“C’mon boys, come on back,” he said. “I got eight of ’em cornered up here. I’ll let ’em out one at a time for ya.”

But no one returned. Since the MiGs were at least 120 knots faster than Edens’ F-84, he had to keep maneuvering to keep from getting shot down. He managed to get off several shots and scored several hits, but the remaining MiGs continued attacking from all directions.

“Cannon-fire tracers were coming at me like golf balls, but when you’re alone, they look like basketballs,” he said. “According to my film, I got eleven of them damaged. But I couldn’t follow up to kill them. I was just trying to survive. Someone told me the whole thing was about seventeen minutes. It felt like seventeen hours.”

Years later, Edens received a letter from the New Zealand and Australian communications unit with a translation of the Russian commander that day yelling at his squadron to “get out of there and leave that crazy American (Edens) alone!”

“He’s already shot three of us down and he’s going to get the rest of you!” the commander yelled.

“Then they scattered like a bunch of quail,” Edens quipped.

An estimated 28 MiGs were in the entire battle. Lt. Jacob Kratt was credited with two MiGs destroyed, Capt. Allen McGuire one probably destroyed, Capt. Bill Slaughter one destroyed, and Capt. Billy Edens zero, although his gun camera films support his sharp memory.

While continuing to fly missions in the Korean War, Edens got shot down again.

“This time I was captured by the Chinese,” he recalled. “I was with about a hundred thousand Chinese infantry. After they fell asleep, about midnight, artillery and mortar started falling and everybody started running, so I started running too. I ran and ran until someone grabbed me like a damn big bear. It was this Army sergeant, and he said, ‘Fly boy, we saw you get shot down and called artillery on them to give you a chance to escape.'”

Edens was relieved and very grateful. He thought he’d return to flying, but his commander decided against it, stating that it was his fifth time crashing.

“For him, the war’s over,” The commander said.

However, Eden, who had flown 153 missions, went on to fly F-100s in Vietnam, becoming a full colonel during his second tour. Col. Billy G. Edens received the Silver Star, DFC with 3 OLCs, Bronze Star, Purple Heart with one OLC, and the Air Medal with 15 OLCs.

He offered some wisdom to young people today: “Try to determine what you you’d like to do and talk to people who have experience doing it.”

Walter R. Groce (3.5 victories)

Walter Raymond Groce was born Oct. 3, 1922, in Plentywood, Mont. When he was young, his mother got sick, and Groce ended up in an orphanage in Great Falls, Mont.

At age 14, he worked as a farmhand in the fields for room and board. At 16, he was a bellhop for the Stevens Hotel and his pay was a room and breakfast. In the morning, he bicycled to St. Thomas Orphans Home, where he studied and ate lunch. Then in the evenings, he’d wash dishes at a restaurant, where his payment was dinner. In his rare spare time, Groce enjoyed making planes out of balsa wood.

With two older brothers already in the service, Groce enlisted in the cadet flying program in the fall of 1942. He attended basic training in Denver, college training detachment in Logan, Utah, and flight school in Santa Ana, Calif. Following that was primary training in Scottsdale, Ariz., and then basic in Pecos, Texas, flying BT-13s. He continued to advanced training at Chandler, Ariz., flying AT-6s and AT-9s, and then gunnery training at Gila Bend, Ariz. Finally, he went to Bradley Field, Conn., where he learned to fly the P-47.

Second Lieutenant Walter R. Groce climbs into the cockpit of his P-47 in July 1944, at Boxted Air Base in England.

“At the time, I didn’t have much confidence in the P-47,” he recalled. “But when we got to the base in England, this guy buzzed the place and did a roll in a P-47. I felt ten feet tall. He sure cheered me up.”

After 30 days of training at Atcham Field, Groce returned to the base and in front of hundreds of new arrivals, buzzed the field and did three rolls.

“Three days later, I was served the 104th Article of War, costing me a month’s pay and keeping me a second lieutenant,” he said. “I stayed an extra 20 days. But I figured that if what I did cheered those men up as much as that P-47 cheered me up when I first arrived, I should’ve gotten a medal.”

In July 1944, Groce joined the 56th FG, 63rd FS.

“My commanding officer was Bunny Comstock,” he said. “Bunny was a great CO and a very nice person. He was fair to everybody and was an excellent pilot.”

On Aug. 28, 1944, Groce got his first victory.

“We were doing a dive-bombing mission on some marshalling yards,” he recollected. “I spotted this Heinkel 111, so I dropped down and shot the daylights out of him. Things were flying off the plane. I had to pull back to keep from running into him.”

On September 21, Groce downed an Fw 190.

“We attacked about 20 Fw 190s and downed about 16 of them,” He recollected.

There were times when victories went unrecorded. Groce had one of those experiences.

“I was firing on an Fw 190,” he recalled. “But I was pulling so much deflection that the enemy plane wasn’t on the film. Then he got into a midair collision. Since I was out of film, nothing showed and nothing was done about it.”

On Nov. 1, 1944, Groce was involved in what he described as “one of the most reviewed gun camera films of the war.” The disputed victory occurred over Holland, from Enschede to Zwolle.

Second Lieutenant Walter R. Groce is pictured in July 1944, shortly after joining the 56th Fighter Group, 63rd Fighter Squadron.

“A German Me 262 jet had just shot down a B-17 and a P-51 (“Hookin’ Bull,” piloted by Lt. Denis Alison),” he said. “The 352nd, 20th and 56th fighter groups all went off in pursuit of him. I saw there was no chance I could go after him. He was heading in a westerly direction. But then he made a right turn, and I went after him. Hitting about 500 mph in a dive, I pulled in behind him, but he was still out of range.

“Then the 262 made a left turn, started climbing a bit and came right at me. When I thought he was in range, I began firing. I rolled over and saw the jet was spinning down, and took some pictures of him. Comstock said, ‘Is that you, hotshot?’ (Comstock’s nickname for Groce was “Hotshot Charlie”) I said, ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘Good for you.'”

All three fighter groups, including six different pilots, tried to claim the jet.

“When I was through with him, he was spinning down,” Groce noted. “I think I hit him in the right engine. They gave me half a credit, but in my mind, I’m the one who shot the jet down.”

Groce says he has the gun camera film and still photos confirming his bullets were the ones that brought the Me 262 down.

Bunny Comstock offered his version of the fight.

“The Me 262 came through our formation and hit one of my people in the left side,” he said. “The 262 proceeded westward and we could see him on top of the bottom cloud layer. Then we spotted him returning. Wally and one other Jug were on him and then two P-51s. The 262 was hit in the engine and was on fire. I support Wally Groce’s claim to a victory.”

On Dec. 2, 1944, Groce recorded his final victory of an Me 109. Also scoring a victory that day over an Me 109 was Second Lieutenant Samuel K. Batson. Batson, who had flown Groce’s wing, had three victories in less than a month but was killed in a crash due to engine failure on Dec. 30, 1944.

“Batson was an excellent pilot and a real nice guy,” Groce recalled.

Groce survived his most frightening mission on Jan. 16, 1945.

“It was the longest mission without a landing,” he said. “Seven hours and 25 minutes before, we had to bail out. We took the worst beating. But not from the Luftwaffe, from the weather.”

Military archaeological records indicate that 16 planes from the 8th AF either crashed or their pilots bailed out that dreadful day: two P-47Ds, eight P-51Ds, one P-51B, four B-24Js, one B -17G and one TB-26C. The North Sea scud could eliminate all visibility. That day, the airfield tried to use its gas heater to raise the fog, but the pilots still couldn’t find the runway.

“In that fog, with all those planes, you’re apt to have a crash,” Groce explained. “We went right over a B-17. I called Boxted, and asked about bailing out east, but Schilling said, ‘No, head west for three minutes and bail out.’ So I did.” The chance of surviving a bailout over land was much greater than the freezing ocean.

After retiring as a captain, Groce graduated from college and worked for Houghton International Inc. for 35 years, retiring in 1985. Today, he lives in Tigard, Ore., with his wife Trula Dae. The Groces have been married 27 years and have nine children between them.

For men of the “greatest generation,” putting the needs of your country before yourself was common. When asked if young people today would volunteer to defend their country like his generation did, Groce replied, “I don’t think so.”

“You wouldn’t get the same response,” he said. “We came up through the Depression. It was a different time. Things meant a lot more to us.”

Russell “Freddy” Fredrickson (3.5 victories)

Russell “Freddy” Fredrickson, 82, at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, April 22, 2006. Today, he lives in nearby Renton.

Born July 5, 1923, in Kenosha, Wis., Russell “Freddy” Fredrickson learned early in his upbringing the necessity and importance of hard work. At age 12, he made 25 cents an hour working for his father as a building contractor.

After graduating high school, Fredrickson was encouraged by two of his friends to enlist with the Army Air Corps in Milwaukee. Before entering the aviation cadet flying program, he attended Black Hills Teacher’s College in Spearfish, S.D., for one year. He attended U.S. Army basic training in Fresno, Calif., preflight school in Santa Ana, Calif., primary training at Wickenburg, Ariz., basic flying school at Lancaster, Calif., advanced in Glendale, Ariz. and gunnery training in Gila Bend.

Fredrickson received his P-47 pilot training at Abilene Army Air Base in Texas, and from there was ordered to the 56th FG, 63rd FS.

“Each and every one of us considered ourselves God’s gift to the aviation world,” he said. “One thing about a fighter pilot—you think you’re the best, even if you’re not. It was part of our training.”

Fredrickson participated in the ill-fated, “at all costs” raid on Arnheim, Holland, led by Bunny Comstock, on Sept. 18, 1944.

“On Sept. 17, 1944, we were designated to destroy flak installations south of the Zuider Zee,” he recalled. “Albright had to bail out and ‘Fairbanks’ (Dave Schilling) had to belly in on the runway at Boxted. Then on September 18, only twelve 63rd FS airplanes were available for the mission. We were looking to drop food to the U.S. Army troops whose rations were in short supply. Instead of fuel, our wing tanks contained packages of K rations. The enemy had flak positions hidden in the forest and they would fire at us after we passed over. Most everyone sustained battle damage. As I recollect, five of the twelve aircraft didn’t return after the mission.”

Many years later, Fredrickson assembled a “military career history” that was given to his grandchildren.

Second Lieutenant Billy G. Edens, at Boxted Air Base in England in May 1944, was one of only a few pilots from the 56th Fighter Group to become an ace as a second lieutenant.

“I didn’t intend on preparing such a document, but Bunny Comstock threatened me with bodily harm if I didn’t,” he said. “He told me, ‘You owe it to your grandkids!'”

Fredrickson read excerpts of those stories, including one from Nov. 18, 1944: “While flying a brand spanking new bubble canopy P-47, I finally got a shot at a few enemy airplanes. Our mission was to strafe an airdrome in the Frankfurt area that allegedly housed a variety of German bombers. I damaged two Heinkel 111s before the group was “bounced” by sixteen Me 109s. Our squadron pulled off the airdrome to get into the air battle. We sighted and split S on three Me 109s that headed for the clouds. Strikes were later confirmed by my gun camera film. My target entered the top of a low overcast and headed straight down. There was no way to confirm the 109 crashed after entering the clouds. I was awarded a probably destroyed in the air and two damaged on the ground.”

Another entry was for Nov. 27, 1944: “Two Me 109s. It was a big dogfight over Dummer Lake. My wingman and I engaged two while my number three engaged the third. I was firing at the number two Me 109 and the leader was firing at my wingman. After downing the number two, I pulled the turn tighter and got the leader. That leader obviously didn’t realize that a P-47 could outmaneuver a 109 any day of the week. He scored no hits on my wingman.”

Another air battle was recorded on Dec. 2, 1944: “My gun camera film confirmed my first target was on fire when it started to dive for the ground. Too many enemy fighters were around to follow it all the way down. I latched on to another 109 and it was almost my undoing. I was too close to the enemy when I fired my guns. The 109 disintegrated and parts came back through my flight path. Smoke poured out from under the fuselage and my element leader advised me to bail out. I said, ‘Not over enemy territory.’ I headed for home. Smoke poured out for the next two hours. How’s that for a tough airplane? A pilot of the 62nd FS hosed off a few rounds at my first target and claimed half a victory. I condescended to give him half if he was that hard-up for recognition. My wingman said that was a big mistake.”

Fredrickson’s last mission in WWII was on Jan. 6, 1945, for a grand total of 64 missions. He became a major stateside and spent four years flying F-80s and F-86s.

On Jan. 29, 1955, Fredrickson married Dottie Orttel. They’ve been married 51 years and have two children, their son Mark and daughter Kyle.

Fredrickson concluded his military service with tours in Japan, the Pentagon, Hawaii, the Air Defense Command, Southeast Asia and the AF Test and Evaluation Center. He retired in 1979, and went to work for Boeing in Seattle.

Fredrickson was awarded the Legion of Merit with one OLC, the DFC and the AM with 11 OLCs. But instead of talking about his honors, he’d rather tell a Bunny Comstock story.

“When I finished my tour in Europe, I was supposed to go to Blackpool, England,” he recalled. “Bunny flew a mission that day, which requires a 3 a.m. wake up. He was dead tired. But he took me to Blackpool in a B-26 anyway. That showed me a lot. He was the only commander in all of England who would do such a thing. I admire and respect him. I can still remember it today and it happened more than 60 years ago. Bunny’s my hero as far as the Air Force is concerned. I’ve always respected him. We’ve kept a real close relationship for more than 50 years.”

Today, the soft-spoken Fredrickson enjoys golf, photography, gardening on his half-acre lot in Renton, Wash., and spending time with his two grandsons, Daniel and Andy. In a final comment, Fredrickson shared a favorite motto: “Always stand tall and never compromise your principles.”

Nothing ordinary

The camaraderie and mutual respect of these men that had survived the years was probably best summed up by Comstock’s final comments.

“Billy Edens was the one of the most popular, well-liked guys in the group,” he said. “Fredrickson was an outstanding wingman who stuck to me like glue. All three of these men (Edens, Fredrickson and Groce) were outstanding pilots and could be relied upon.”

So much for ordinary men. There was nothing ordinary about these men or their generation.