By Robert Louis DalColletto

Lt. Col. James Warren poses in a studio in Sacramento, Calif., for the cover story of Senior Magazine, in November 2000.

In the summer of 1942, James C. Warren, a 19-year-old underprivileged young black man from Gurly, Ala., read the August issue of American Magazine. An article titled “I Got Wings,” written by Second Lieutenant Charles H. Debow, touched him deeply. Debow was one of the first five black cadets to graduate at Tuskegee Army Air Field and earn his silver wings.

“I was so proud; it brought tears to my eyes,” Warren recalled. “The thought of ever being a part of that program never even touched my mind.”

Determined to overcome limited resources and racial discrimination, Warren went on to become one of the venerable Tuskegee Airmen. As an officer in the 477th Bombardment Group, he was one of the first 19 arrested during the “Freeman Field Mutiny” of 1945; 162 black officers were arrested for demanding lawful entry into the white officer’s club at Freeman Field, Ind. Nine years before Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks refused to obey the busing laws in Montgomery, Ala., the 477th BG was the first group to challenge a major department of the U.S. government on civil rights.

With more than 12,000 hours of flying and service in three wars, Warren’s extraordinary flying career reached a pinnacle in 1973. He was selected as navigator on the first C-141 to fly into North Vietnam to return the first group of POWs to Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines.

The achievements of Lt. Col. James Warren didn’t stop there. Because of his diligence and convincing research, 50 years after the incident at Freeman Field, the Air Force removed the reprimands from the permanent military records of the arrested officers.

Young man in Alabama

Warren was only 2 years old when his father died in 1926. He was forced to start working at a very young age.

“I never had a childhood,” he said. “In the summer, I’d get up early and pick blackberries and sell them to the white folks for 10 to 15 cents a gallon. I’d catch crawfish and sell the tails for bait. I also sold the Pittsburgh Courier for 10 cents a copy in Gurley, and then I’d walk barefoot five miles to Paint Rock and sell the rest. I’d use the money to buy shoes for the winter. In the fall, I’d work in the cotton fields.”

Warren couldn’t attend school until the cotton fields were picked in late October. School was let out in March, so Warren and the other children could return to the cotton fields for tilling and planting.

Second Lieutenant James Warren visits the architectural firm where he worked in Chicago just before departing on active duty in March 1952.

Despite his personal hardships, Warren had a positive early influence. His mentor was Charlie Powell, a senior black man who had a collection of books discarded by white folks. Each time they met, he would offer Warren a new book to read.

“I knew I had to read the books because he was going to ask me questions about them whenever we met,” he said. This encouraged Warren’s appetite to learn and fueled his determination to succeed.

In 1938, at age 15, Warren left Gurley. He settled in Highland Park, Ill., just north of Chicago, while his mother took a job as a live-in maid in Winnetka, Ill. He attended New Trier Township High School, where 2,800 students were enrolled, but only 13 were black. Warren was driven to excel, and learned early how to turn adversity into opportunity. In his senior year, he made the honor roll with a pre-engineering curriculum and graduated in June 1942.

Mistakes and opportunities

With no chance of entering college at the time, Warren took on a job at a drugstore. Then a boyhood friend, Warren Spencer, told him about the new Civilian Pilot Training Program, and a test being given at the Wabash YMCA in Chicago to qualify. Originally the program was open only to whites, but an amendment to Public Law 17 authorized the formation of seven units, five at predominantly black colleges.

Willa Brown, who ran a flight school at Harlem Airport in Chicago, conducted the test. Warren passed it, qualified for the program, and was ordered to report to Harlem Airport on Oct. 22, 1942.

When he arrived, Brown advised Warren he had to take the Air Corps cadet qualifying test, but told him he shouldn’t score too high, because it would make him ineligible for the CPT program. Completing the aviation cadet exam in an hour and 25 minutes, Warren scored very high. He was disappointed because he felt he wouldn’t be allowed to continue in the CPT program and went home. He later discovered he had made a big mistake. Had he returned to Harlem Airport, he would have been admitted to the CPT program.

Undaunted, he enlisted in the Army Air Forces on Nov. 19, 1942, and was called to active duty March 1943. Boarding a train, Warren left Chicago for Keesler Air Base in Biloxi, Miss.

“Once we crossed the Mason Dixon Line, the conductor dragged me out of my seat and put me into the first car,” he said. “It’s the worst place to be, because soot and cinders are prevalent throughout the car.”

After attending basic training at Keesler Field for less than a month, Warren was assigned to the College Training Detachment at the Tuskegee Institute for 11 weeks. The training of black American pilots began there on July 19, 1941. On March 7, 1942, only five of the original 13 black candidates got their wings. Although training proceeded slowly, enough pilots graduated to form the 99th Pursuit Squadron.

On June 19, 1943, Warren entered pre-flight cadet training at Tuskegee Army Air Base. Following the completion of preflight, he returned to the campus for primary flight training. After three weeks, one of the white directors informed Warren and his class that there were too many cadets in the class and that 10 had to go. A week later, after two difficult check rides in which he was instructed to do maneuvers he hadn’t been trained to do, Warren was eliminated from the program.

“It was the most devastating night of my life,” he said.

Because of the education and training level of the ex-cadets, they were assigned in all administrative areas at the airfield. Warren was assigned to the personnel unit.

Flight Officer Warren

In October 1943, all former cadets (121 in total) were sent back to Keesler Field, Miss., to determine their qualifications for training as navigators or bombardiers. After three days of testing, only seven were selected.

“I was one of the seven, but none of us ever believed the results were valid or correct,” Warren explained. “They didn’t know what do with us. We remained at Keesler for several weeks. We made up our own squadron. We’d be first in line at the dining hall, then disappear into the library all day.”

Eventually the Air Force qualified 33 individuals, including Warren, and sent them to pre-flight training at Tuskegee, followed by navigation school in Hondo, Texas. After arriving in Hondo early in the morning on Easter Sunday, the 33 cadets attended a church service where they were seated in a separate section. Afterwards, the group was introduced to their classroom: a tarpaper shack in an open field, away from the regular classrooms, but still on the main base.

First Lieutenant William Ellis (in front) and (L to R) Capt. Richard Stanton, Flight Officer Warren and Second Lieutenant Leroy Roberts leave Godman Field for some recreation in the fall of 1945.

“We worked all afternoon cleaning it up in 100-degree heat,” he recalled. “We lived in barracks by ourselves. We marched in our own formation, and we always won the competition for best marching unit. But we weren’t allowed in the cadet club. We had to go to the back door to order food. A couple guys who were light-skinned enough to pass for white went to the front door and ordered. We considered that a victory.”

Navigation school lasted from April until graduation on Aug. 24, 1944, of class 44-11-9B; the “B” was for black. Thirty of the 33 ex-cadets graduated.

“I was given the rank of flight officer when I should have been second lieutenant,” Warren said. “The board was supposed to determine if we were to be rated as flight officers or second lieutenants. But there was never a board held.”

On Feb. 4, 1945, Warren graduated from bombardiering school at Midland, Texas, dual rated as a navigator and bombardier.

The 477th Bombardment Group

In mid-February 1945, F.O. Warren joined the 477th BG at Godman Field, Ky., where all the commanders were white. Commander Col. Robert Selway’s hostility toward the black bombardment program was reflected by his commander, Maj. Gen. Frank O’Donnell “Monk” Hunter, a decorated ace from WWI who resented being associated with bombardment groups, especially one including black flyers.

On Oct. 30, 1925, the Army War College conducted a study titled “The Use of Negro Manpower in War.” Signed by the commandant, Maj. Gen. H.E. Ely, the study concluded that black men believed themselves to be inferior to white men and lacked initiative and resourcefulness. The report claimed, “Negro officers not only lacked the mental capacity to command, but courage, as well.”

The 477th BG was activated at Selfridge Field, Mich., on Jan. 15, 1944. One day, with the Selfridge base theater full of black officers, Hunter laid down his law.

“The War Department is not ready to recognize blacks on the level of social equal to white men,” he said. “This is not the time for blacks to fight for equal rights or personal advantages. … Anyone who protests will be classed as an agitator, sought out and dealt with accordingly. This is my base, and as long as I am in command, there will be no social mixing of the white and colored officers. The single officer’s club on base will be used solely by white officers.”

“Gen. Hunter was more interested in keeping the clubs segregated than getting our group ready for overseas combat,” Warren said.

Second Lieutenant Warren in 1952, after a morning mission; B-26 Night Intruders are in the background.

On May 5, 1944, all gates at Selfridge Field were locked. The 477th BG was moved to the small, dilapidated Godman Field in Kentucky. In late February 1945, a few weeks after Warren joined the 477th BG, the Air Force started moving the group from Godman to Freeman Field, Ind., a far superior facility. On April 3, 1945, two days before the last officers were moved, a group of officers, including Warren, gathered around a lone B-25 at Godman Field, and discussed what awaited them at Freeman.

“Several of us read a copy of a letter dated April 1, 1945,” Warren explained. “Col. Selway had designated the former noncommissioned officer’s club as ‘Officer’s Club Number One’ for black officers (who called it “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and refused to use it) and ‘Officer’s Club Number Two’ for supervisor and instructor personnel (who were all white). We decided that once we got to Freeman Field, we’d take action.”

The Freeman Field Mutiny

That evening the officers had a meeting.

“We decided there was only one thing left to do: go to the club,” Warren said.

The officers agreed their confrontation must be a non-violent, direct action. If arrested, they would simply leave the club, but continue entering it in small groups.

On April 5, 1945, a train arrived at Freeman Field with Warren and several other officers. Once settled in, they put their plan into action. The first officer to enter was 2nd Lt. Marsden A. Thompson. Two paces into the club, Lt. J.D. Rogers, the “Officer of the Day,” met Thompson; 2nd Lt. Coleman A. Young, only a few feet behind, saw Rogers grab and push Thompson. Warren heard Thompson tell Rogers, “Take your hands off me.”

While Rogers and Thompson conversed, Warren and several other officers entered the club. When the first 19 officers refused to leave, they were arrested and returned to their quarters. Meanwhile, a group of 14 more officers entered the club, then later, another group of three. That night, a total of 36 black officers were arrested. The next day, 25 additional officers in small groups entered the club (some of which were combat veterans from the 332nd FG) and were arrested, bringing the two-day total to 61 arrested.

On April 9, with the help of Col. Wold and Maj. Osborne, Col. Selway created base regulation 85-2, and added an endorsement stating that anyone signing it understood it and would obey. By signing it, the officers agreed to being segregated and discriminated against. The following day, Warren and a hundred other officers refused to sign the new regulation.

“My commanding officer said, ‘I order you, Flight Officer Warren, to sign base regulation 85-2. Do you intend on carrying out my orders?'” Warren recalled. “I told him, ‘I have no statement to make, sir.’ He replied, ‘I am ordering you under arrest for disobeying my order.'”

Lt. Col. Warren takes the navigator’s seat for a final flight aboard the infamous C-141 known as the “Hanoi Taxi” on May 6, 2006, at Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio.

Of the 400 black officers stationed at Freeman Field, 101 refused to sign and were placed under arrest. Hunter and Selway tried to charge the officers with Article 66 (mutiny) and 64 (disobeying a direct order from a superior officer in a time of war, punishable by death) of the Articles of War.

“It didn’t bother me a damn bit,” Warren said. “We were young, educated, well trained and determined.”

Two days after their second arrest, the officers were ordered to march to the flight line, where six C-47s awaited. Harold J. Beaulieu, a black, non-commissioned officer in charge of the photo lab at Freeman Field, rigged up a camera in a shoebox and took a photo of several officers on the tarmac with their belongings. On April 28, 1945, the photo appeared on the cover of the Pittsburgh Courier with the headline, “61 Pilots Arrested, Offense?—Visiting White Officer’s Club,” and an in-depth story. Irate American citizens flooded the War Department with more than 50,000 telegrams.

The C-47s took off from Freeman Field with 101 officers wondering if they were headed to the prison at Fort Leavenworth. They soon realized they were heading back to Godman Field, the air base they departed only eight days earlier. When they arrived, dozens of military police were waiting for them, armed with submachine guns.

“The German and Italian POWs, walking freely without guards, were laughing at us,” Warren said.

Meanwhile, Hunter, Col. Malcolm N. Stewart (acting chief of training, Headquarters First Air Force), Lt. Gen. Barney M. Giles (deputy commander, Army Air Forces) and Gen. William W. Welsh (chief of staff for training, Army Air Force) were busy discussing their next moves over the phone. It was a normal process to record the officer’s telephone conversations using huge wire recorders and later transcribing the recordings.

For 28 years following the end of the war, these conversations were classified top secret. But in 1973, at the insistence of Col. Alan Gropman, author of “The Air Force Integrates,” the files were declassified. Warren got access to these transcripts, which included a statement Welsh made in reference to the 477th BG: “Maybe we can eliminate the program gradually and accomplish our end.”

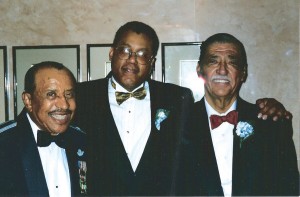

L to R: Lt. Col. James Warren, Lt. Col. Lee A. Archer and Maj. Sgt. Wayne Wellington at the Tuskegee Airmen National Convention in Phoenix in August 2006.

On April 12, 1945, President Roosevelt died and Harry S. Truman became president. Five days later, all officers at Godman Field were released from arrest with the exception of Thompson, 2nd Lt. Shirley R. Clinton and 2nd Lt. Roger Terry, who were put on trial. Clinton and Thompson were found not guilty, but Terry, who had “jostled a superior officer,” was found guilty of “offering violence” and fined $150.

On July 1, 1945, Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr., commander of the 332nd FG in Italy, officially took command of the 477th BG and all white personnel were removed. But on Aug. 14, 1945, WWII ended; the 477th BG never saw combat. On March 12, 1946, Warren was released from active duty and returned to his home in Evanston, Ill.

However, the effectiveness of the non-violent, conscience-driven efforts of the 161 total officers arrested at Freemen Field was evident by President Harry Truman issuing Executive Order 9981, bringing an end to official segregation in the armed forces in 1948.

But for Warren and the other arrested officers, the reprimands doled out by Hunter stuck to their records and proved devastating. The statement, “He displayed an uncooperative and stubborn attitude toward constituted authority,” plagued Warren’s career. Consequently, no arrested officer in the Freeman Field mutiny ever got a rank higher than lieutenant colonel.

Recalled to Korea and Vietnam

Warren and Xanthia F. Cooper were married Aug. 26, 1950. Warren had a son, James Collins Warren Jr., by his first wife, and he and Xanthia had two sons together, Stewart Tyronza and Dwayne Collins. All three of Warren’s sons eventually served in the military.

Warren attended the University of Illinois, majoring in architecture, but left his senior year to accept a job with an architectural firm in Chicago. He was recalled to active duty March 13, 1952, for the Korean War.

“The orders had me listed as white; there was a parenthesis after my name with a ‘W’ inside. I think that’s why I got recalled. I was dual rated, so they must have figured, ‘He must be white,'” Warren said, showing his sense of humor and irony.

After being ordered to refresher training, B-26 combat crew training and survival school, Warren reported in November 1952 to the 17th Bombardment Group in Korea. On his third mission, he dropped three bombs at a road intersection and destroyed some vehicles.

“After I got back to my quarters I became quite upset,” he recalled. “The next morning, I found a chaplain and asked him what God thought about what I had done? He told me the heavenly Father would hold the people who sent me there responsible. Well, that was good enough to get me over the bumps.”

During his tour of 50 missions, Warren destroyed more than 50 vehicles.

L to R: Lt. Col. Warren, D. Michael Collins (deputy, Equal Opportunity) and Roger Terry (president, Tuskegee Airmen, Inc.), after the 1995 announcement that the Air Force was removing letters of reprimand from the military records of the 477th BG.

“I directed the plane over the target, gave control directions, aimed the bombs and released them,” he said.

The B-26 Night Intruder carried six 500-pounders internally and two on each wing.

“We also did strafing at night,” he recalled. “I would call out the altitude and warn the pilot to pull up so we wouldn’t hit any mountains. We got hit quite a few times but were never shot down. Sometimes I even had three missions in one day. With no briefing, they’d just give you paperwork and you’d go right back out. ”

Warren’s final mission, number 50, was on July 22, 1953. Five days later, the war ended. Warren also served in Vietnam, totaling 123 missions.

Homecoming One

Warren’s flying career was highlighted by being selected as the navigator on the first C-141 to fly into Gia Lam Airbase in Hanoi, North Vietnam, to return the first group of POWs to Clark AB in the Philippines.

On Feb. 12, 1973, Maj. James Marrott commanded aircraft 60177, call sign “Homecoming One.” Warren said once on the ground at Gia Lam, they were instructed to “cock the aircraft,” and be ready for immediate takeoff once the ex POWs were aboard.

“When we were taxiing out, one of the passengers asked me to tell him when we were three miles out (in international waters). I told him, ‘Don’t worry, you’re going home today.’ We left the cockpit door open, and when we rotated off that runway, the loudest roar of joy came up from the cabin. I can still hear it today,” Warren reminisced with a smile.

His friend of many years, Maj. Fred V. Cherry, was also aboard the rescue craft. Cherry, an Air Force F-105 fighter pilot, had been shot down in October 1965 and was a POW for seven years and five months.

“Twenty minutes into the flight, Cherry walked by the cockpit and saw me. We hugged each other for about five minutes,” Warren said.

During a CNN interview on May 12, 2004, Cherry was asked about a photo taken on the “Hanoi Taxi,” in which Warren is lighting a cigarette for him. Cherry explained that he didn’t initially know that Warren was on the plane.

“He was the navigator for the flight,” he explained. “He didn’t know what psychological condition I might be in, so he got the word to me quietly that he was in the cockpit. I remembered him very well.”

Being navigator of such a historic flight is one of Warren’s fondest memories.

“My flight jacket, flight suit and cap from that mission are in an enclosed glass case at the Air Force museum,” he said. “In the background is a huge blowup of that photo.”

After 35 years of service, Lt. Col. James Warren retired from the Air Force on Nov. 1, 1978.

A dream comes true

When Warren read “The Air Force Integrates,” by Col. Alan Gropman, he was encouraged by the documents Gropman had used. It renewed his hopes of convincing the Air Force board for the corrections of records to remove the reprimands on his records, as well as the other airmen. Warren also sought to fulfill another dream: to completely and accurately tell the story of the mutiny at Freeman Field.

For three years, he researched, wrote and rewrote his manuscript.

“I would get tired and quit writing,” he admitted. “I was so angry. I tried to get the reader as angry as I was. That ruined the story. My wife suggested that I simply just tell the story.”

“The Tuskegee Airmen Mutiny at Freeman Field” was published in July 1995.

“At that time, I wrote to the board and made my request for the removal of my reprimand from my records,” he said. “I also wrote the assistant secretary of the Air Force, Rodney Coleman, and requested his assistance.”

On Aug. 12, 1995, at the Tuskegee Airmen Annual National Convention, held in Atlanta, Warren and his fellow officers were vindicated. With Warren in attendance, Coleman announced that all the arrested officers would have the reprimands removed from their records, provided they submit Air Force form DD-149.

The Air Force also set aside the court martial against Terry. Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Ronald Fogleman presented the official document to Warren. The audience cheered and many were brought to tears. Warren, emotional and victorious, pumped his fist triumphantly.

“Emotionally, it meant a great deal,” he recalled. “I accomplished something everybody said I couldn’t do. It was more than an incident, more than just going into the officer’s club. We were the first group to challenge a major department of the U.S. government on civil rights.”

Still flying high

In his career, Warren was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross with two oak leaf clusters, the Air Medal with 11 OLCs, and the Meritorious Service Medal with three OLCs.

On May 6, he attended a special event at Wright Patterson AFB in Ohio. More than 200 former POWs were there to witness the retirement of the C-141. Warren took one last flight at his navigation station.

In public and privately, Warren is friendly, candid and informed. A seasoned storyteller, he combines fact, humor, wit and passion to inspire and motivate audiences, large or small. On August 21, at the Great American Ball Park in Cincinnati, he threw out the ceremonial first pitch before the scheduled game between the Reds and Astros. For two weeks prior to throwing the pitch, he practiced in his backyard. In high school and after WWII, he played baseball, sometimes as a pitcher, but primarily as a catcher. With his pride on the line, his pitch passed home plate and he received a standing ovation.

The Warrens live in Vacaville, Calif., where he is currently writing his autobiography. When Warren was reading Debow’s article, little did he know how well he would follow in his footsteps. At age 83 and going strong, he’s a great example of the power of self-reliance and the resilience of the human spirit.