By Daryl Murphy

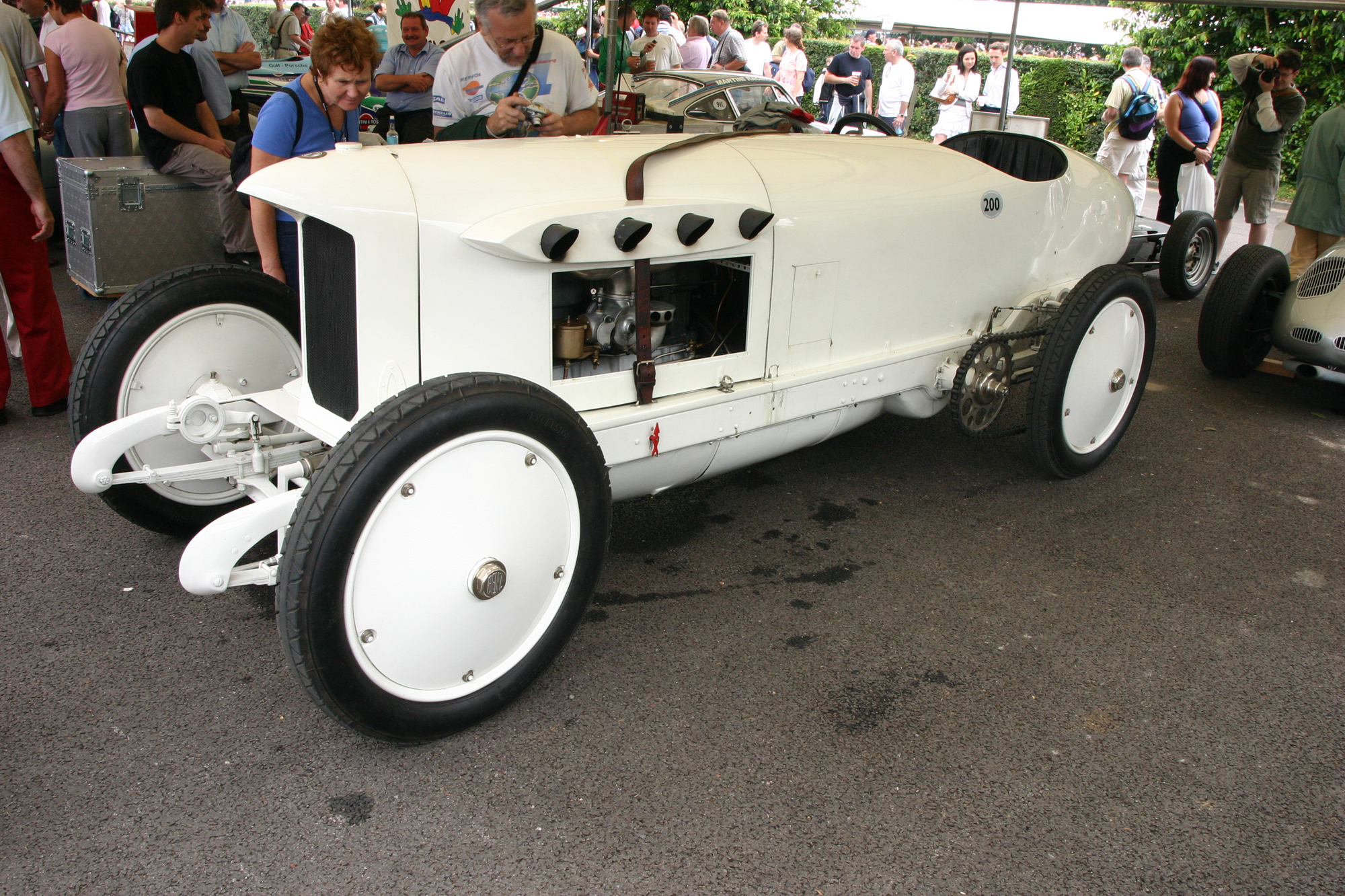

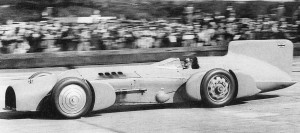

The chain-drive Benz 200 Blitzen Benz caused a sensation in 1909, with its 12.5-liter, 200-hp, four-cylinder engine. Barney Oldfield drove it in American exhibitions, and Bob Burman used it at Daytona Beach in 1911 to set a world speed record of 141.4 mph

Following the birth of both the airplane and the automobile, man had a need for more power.

It was aviation’s most precious commodity—the energy to lift a fragile craft into the air and keep it sustained there for some time and distance. In the automobile, however, anything past a reasonable level of power was largely wasted. Once a ground-bound vehicle reached a comfortable speed, the need to go faster wasn’t necessary—well, at least in theory.

Every era has those who have a penchant for speed, and the first few decades of the twentieth century were no exception. By 1909, the 12.5 liter (763 cu. in.) Blitzen Benz had raced to more than 125 mph at the Brooklands racecourse in England, and other speed enthusiasts were setting out to make names for themselves, just as World War I was breaking out in 1914.

The nature of aero engines

All piston engines are the products of their intended use. Auto engines are designed to produce power and torque over a wide variety of engine speeds, in order to accomplish a wide variety of tasks—and they don’t necessarily have to be especially lightweight. Aircraft engines, however, must have a high power-to-weight ratio and generate their torque and power in a narrower speed band, which must fit within the limits of a propeller’s efficiencies.

Those theories were being slowly developed, but in the first decade of the century, they were moot points. It would be a few years before auto engines would be designed to run at speeds much higher than 3,000 rpm. Increased displacement was the easiest formula for increased power. Existing methods demanded a monster engine to produce even a hundred horsepower, and shoehorning that power plant into a roadworthy automobile was difficult, but not impossible. Most aircraft engines of the day were liquid-cooled; adapting them for road-going duty was natural.

In an airplane, designers weren’t as constrained. If a monster engine was needed to get sufficient power, the airframe was simply expanded and adapted (the laws of aerodynamics and engineering were yet to be completely identified). Many of the early auto manufacturers, especially those in Europe, dabbled with ideas of using aero engines in automobiles. Daimler, Darraq, Renault, Hispano-Suiza and Rolls-Royce made some effort, but Italian manufacturer Fiat developed one of the earliest hybrid automobiles, the Tipo.

The Beast of Turin

An outrageous creation that debuted in the early 1910s, the Tipo (Type) S76 was built by the Fiat factory in Turin presumably to break the world’s Land Speed Record, which then stood at 125.95 mph. The chassis was a flimsy 1907/08 Fiat production unit with a Tipo S76DA six-cylinder airship engine of 28.4 liters (1,730 cu. in.), which developed 300 hp at 1,900 rpm.

Standing about five feet high at the radiator cap, the frighteningly top-heavy car was referred to as The Beast of Turin. Except for a brief appearance in England at the Brooklands racecourse, where it was timed at about 90 mph, it never made an impact on any records and was returned to the continent to be lost during the confusion of World War I.

Toodles

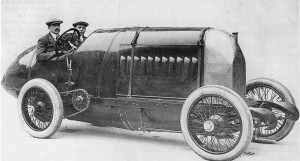

Before WWI, English auto manufacturer Sunbeam also manufactured aero engines. In order to speed up the aero development, Louis Coatalen, the company’s chief engineer, hit on the idea of installing one of their nine-liter (552 cu. in.) flathead V-12s into a Sunbeam auto chassis. Named Toodles (short for “Toodle-loo”), the car generated a great deal of publicity for the company. In addition, because they had been testing flying machines in a country that doesn’t have many good flying days, the idea to test the engine in an automobile was downright brilliant.

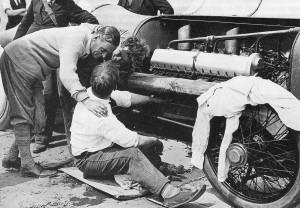

Capt. Malcolm Campbell (left) fraternizes with his mechanics, who are at work on the 350-hp Sunbeam at a 1925 Brooklands meet.

The engine was destined to become the Sunbeam Mohawk, which would later be used in the coming war. As the 1913 V-12 Sunbeam, the car lapped the Brooklands course at 114.49 mph. The car was shipped to America and raced by Ralph de Palma. He sold it to the Packard Motor Car Co., which used the engine in 1916 to inspire the design of the world’s first production 12-cylinder automobile, the seven-liter (424 cu. in.) Twin Six. Not coincidentally, the company premiered its 14.8 liter (905 cu. in.), 250-hp V-12 aircraft engine the next year.

After the war, Coatalen built another aero engine racer, the 350-hp V-12 Sunbeam. This car had a 1,118 cu. in. (18,322 cc) Sunbeam Manitou engine that had been built for RNAC flying boats. The engine had three overhead valves per cylinder and was tuned to produce 355 hp at 2,100 rpm. In 1922, the racer was timed at more than 134 mph. Capt. Malcolm Campbell bought the car in 1923, and modified both the engine and the coachwork for more speed. He renamed it Bluebird. In 1926, he was rewarded with an official world record speed of 150.766 mph.

Chitty Bang Bang

Count Louis Zborowski enjoyed racing and tearing up deserted English countryside roads in his 23-liter Chitty Bang Bang I.

The namesake of Ian Fleming’s 1968 children’s book, “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang,” wasn’t entirely a flight of fancy. Chitty Bang Bang was a name given to two aero-engine, chain-driven cars that were the creations of Count Louis Zborowski, a wealthy patron of motor racing. While the name suggests the noise made by the engine, it actually came from the lyrics of a lewd WWI song. This was a standing joke, said to be entirely in keeping with the temperament of the car’s owner.

Zborowski’s stable included a 1914 GP Mercedes and a 1919 Ballot, and he raced a Bugatti at Indianapolis. He returned home with a new American Miller race car.

His Chittys were built for pure fun on the track and on the open road. They were the first of the amateur-built, postwar aero-engine monsters.

Chitty I was created in 1921 after Zborowski obtained a war reparations Maybach aero engine from a Gotha bomber. The 23-liter (1,409 cu. in.) six had four overhead valves per cylinder. At a modest speed of 1,500 rpm, it put out 300 hp. The chassis was an old Mercedes that had been lengthened and topped by a primitive aerodynamic body. To show it was all in fun, the exhaust pipe ran the length of the body and culminated with a turned-up tip with conical shield.

The initial Chitty was a sensation at its first Brooklands outing. Zborowski won a short race at 108 mph, ahead of a Mercedes he also owned. More track successes followed, and the count enjoyed tearing up deserted roads in the English countryside as well.

In the summer, however, Zborowski laid plans for Chitty II, based around another wartime aero engine he had acquired, a Benz Bz IV. The six-cylinder overhead valve engine of 18.8 liters (1,152 cu. in.) was rated nominally at 230 hp. The chassis was a prewar Mercedes, probably from about 1907; drive was by chain, and it was given a narrow four-seat body, fenders, windshield and lights for the road. In its only race, it placed second under a handicap system, although it had lapped Brooklands at more than 108 mph.

In 1922, Zborowski and his wife drove Chitty II across France to Algeria, to the edge of the Sahara Desert. Because of the lack of radiator water, the engine was damaged to the point that the count had to return to Chitty I for racing. At the Brooklands, he achieved his best speed, one 2.75-mile lap at 113.45 mph. The car was destroyed that fall, in a racing accident, and was subsequently dismantled. Zborowski was killed driving a Mercedes in the 1924 Italian Monza Grand Prix. After his death, Chitty II went through a series of owners, including the family of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Today, it’s on exhibit at the Frederick C. Crawford Auto-Aviation Collection in Cleveland.

Babs

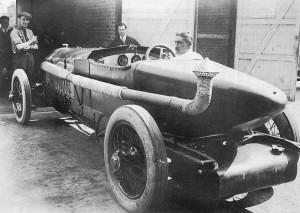

Zborowski built the Higham Special, named for his manor, the Higham House, in 1924, for a land speed record attempt. The monstrous racer was created around a World War I Liberty V-12 engine of 27 liters (1,637 cu. in.).

At Brooklands, Zborowski was able to lap the track at 116 mph. After the count was killed, race car builder Parry Thomas bought the Special (reputedly for £125), modified the engine, added a marginally streamlined body and rechristened it Babs.

In 1926, he took it around Brooklands at a world record 129 mph. Thomas then drove the car on the sands at Pendine, Wales, and was timed at 169 mph. Malcolm Campbell subsequently raised the record to 174 mph, in Bluebird. Thomas returned with a more streamlined car in 1927, but on his first run, he crashed and was killed. His crew took Babs into a local garage for an examination, then buried it in the sand and covered it with rocks.

Subsequently, the English Ministry of Defence acquired the site for use as a firing range, and the “grave” was paved over with concrete. In 1969, Welshman Owen Wyn Owen received permission to excavate the famous racer, and over the next 15 years, painstakingly restored it to working order.

The aerodynamic era

Sir Malcolm Campbell takes a parade lap at Brooklands, after driving Bluebird to a world record 246.09 mph on the sands of Daytona Beach in 1931. From the look on Campbell’s face, it’s evident that the three-ton car wasn’t especially suited to low speeds.

As the quest for speed began to escalate, it was evident that the record venue had to change. The LSR attempts, largely a British obsession, had first been held on the banked track at Brooklands, then at Pendine, a seven-mile stretch of flat, wet sand on the Welsh coast. But as speeds of more than three miles a minute became attainable, a longer course was necessary to gather speed—and to dissipate it.

America’s Daytona Beach was a logical choice. It had been employed for speed attempts since 1905. In 1907, future aircraft designer Glenn Curtiss exceeded 135 mph there on a Curtiss V-8-powered motorcycle. If anyone, including the British, wanted the record, they had to come to America.

In 1929, Englishman Henry Seagrave drove his 1,000-hp Sunbeam, powered by two V-12 Matabele aircraft engines, to 202.98 mph at Daytona, breaking the record Campbell had set at Pendine. Campbell traveled to Florida a year later and raised the mark to 206.95 mph. A scant two months later, American Ray Keech upped the ante by a few clicks of the timing clock, with his Triplex Special, a car powered by three 400-hp Liberty V-12s.

Hearing that Seagrave was building a new car, Campbell revised Bluebird with a sleeker, lower body, new mechanical components and a 1,450-hp Napier Lion. He returned to Daytona in 1931 to raise the record to 246.09 mph. Two years later, a Rolls-Royce R replaced the Napier. That engine had powered the Supermarine S6B to the final Schneider Cup win.

With 37 liters (2,240 cu. in) and 2,500 hp, achieving a new LSR of more than 272 mph was no problem. The Daytona course, however, was becoming a problem. A move was made to the nearly unlimited and smooth surface of America’s Great Salt Lake. At the Bonneville Salt Flats, in September 1935, Bluebird exceeded 300 mph.

Two years later, George Easton’s Thunderbird went Campbell one engine better, installing two Rs to raise the target to 312 mph. John Cobb, whose earlier exploits in a 23-liter Napier Railton were well known at both Bonneville and Brooklands, answered the call with the Railton Mobil Special. The startlingly beautiful, teardrop-shaped streamliner, covering an S-shaped chassis, carried two Napier Lions that drove all four wheels.

The aluminum body of the Railton Mobil Special is lowered over owner/driver John Cobb. Twin Napier Lion W-12 aero engines powered the car to nearly a 400-mph average speed at Bonneville in 1947.

While Cobb waited his turn at the salt flats, Easton pushed the record to 345.49 mph. A few weeks later, Cobb set a mark just above 350 mph, but the next day Easton answered with a run at 357.5 mph.

In 1938, Cobb returned to Utah and flashed through the measured mile in less than 10 seconds, averaging 369.7 mph. Although the war would delay competition, he returned in 1947 to set a record of 394.196 mph, with one of the required two-way runs at a speed of just over 400 mph. The record stood for 16 years. While the next generation of LSR cars would also be aero-powered, the Railton Mobil was the last of the aero piston-engine land speed record breakers.

The jet age

World War II furnished a tremendous catalyst to increased power and reliability for aircraft piston engines, but it also spurred the development of the gas turbine. The tremendous cost and unavailability of turbojets made them impractical for speed attempts.

However, a new racing sport was invented in the early fifties: drag racing. An early enthusiast was Art Arfons, a tinkerer and car buff from Akron, Ohio. After seeing his first race in 1951, he decided to build a dragster.

Not a sophisticated engineer, Arfons reasoned that excessive power was a good place to start, so he purchased a war surplus Allison V-1710 that produced 1,200 hp at 3,200 rpm. (At that time, the best a hot rodder could get from a modified automotive engine was perhaps 400 hp.) He mounted the 1,600-lb. engine amidships on a two-ton Ford truck chassis, retaining the dual wheels for added traction. Aptly named the Green Monster, it was an awkward machine, but he had reasoned correctly. In its first season, it set a record speed of 144 in the quarter-mile.

Arfons went on to build a dozen more Monsters, powered by big-bore aircraft engines, before someone suggested he might want to try a turbojet and go for the land speed record. He acquired a GE J-79 engine off a B-58 Hustler, bolted it onto a tube frame and covered it with a garish Buck Rogers body. In 1964 and 1965 , he set world marks at 434 mph, 544 mph and 572 mph.

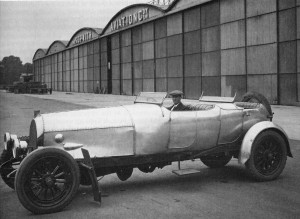

While working for Sopwith after WWI, Harry Hawker, Australian pilot and aircraft designer, used his Sunbeam-Mercedes for fast transportation. He had to lengthen the Mercedes chassis by 10 inches in order to accommodate the 225hp Sunbeam V-12 aero engine.

A turbofan-powered car holds today’s absolute LSR of Mach 1.016 (763 mph). Class records apply for three-wheeled and rocket-powered cars, those that use jet-thrust and those with turbine-driven wheels. Almost forgotten are the good old-fashioned piston-powered machines. A sleek streamliner with four Chrysler Hemi V-8 engines set the current record in 1965. It was clocked at 409 mph, just a bit faster than the mark set by John Cobb in 1947.

The era of the aero-engine race cars may be over, and today’s enthusiast may have never had the opportunity to witness the sound and the fury these monsters created. But airplane folk can still have that experience every time a Merlin, a Double Wasp or a Cyclone, at full tilt, makes a high speed pass at Oshkosh.

Andy Granatelli summarized it best after his Pratt & Whitney PT6-powered racer was effectively banned from the Indianapolis 500.

“They outlawed the turbine car ’cause it doesn’t make good noises!” he exclaimed.

References:

“Aero-Engined Racing Cars at Brooklands,” Bill Boddy, Haynes Publications, 1992

“Aircraft Piston Engines,” Herschel Smith, McGraw Hill, 1981 Splendid Whizz Association

[http://www.peterrenn.clara.net]