By Di Freeze

Al Ueltschi speaks at the Crystal Ball for Sight, after receiving the ORBIS Lifetime Achievement Award for his contributions to eliminate unnecessary blindness globally.

Two types of salvation are especially near and dear to the heart of A.L. Ueltschi, Airport Journals’ 2006 Lifetime Aviation Entrepreneur. The first is the saving of lives. The other, equally important to him, is saving sight.

Ueltschi accomplishes the first mission through FlightSafety International, the world’s largest provider of aviation services and training. The company’s mission is helping its customers in their quest for safe, reliable transportation.

“In doing that, we’ve helped save lives as a matter of course,” said Ueltschi, founder and chairman of the company.

Ueltschi, who has accumulated more than 35,000 hours of flight over the years, says the best safety device on any aircraft, anywhere, remains a well-trained pilot. More than 75,000 pilots, technicians and other aviation professionals train at FlightSafety facilities each year. The company designs and manufactures full flight simulators for civil and military aircraft programs and operates the world’s largest fleet of advanced full flight simulators at more than 40 training locations.

Ueltschi, 89, is also the chairman of ORBIS International, an international nonprofit organization dedicated to saving sight and eliminating unnecessary blindness worldwide. Since 1982, when the Flying Eye Hospital took off on its first sight-saving mission, more than 124,000 healthcare workers have enhanced their skills through ORBIS training programs in more than 80 countries. Thanks to ORBIS and ORBIS-supported programs, more than 135,000 eye surgeries have been performed, and more than three million individuals have been treated.

Although Ueltschi attributes “just plain luck” as part of the reason for his accomplishments in life, he doesn’t rely on luck in either of his life’s largest missions. Both ORBIS and FlightSafety work hard to accomplish their goals.

Early life in Kentucky

Ueltschi says his “great luck” goes back as far as the 1880s, when his grandparents came to America, leaving friends and family behind in Switzerland.

“If my grandparents had stayed in Switzerland, imagine what would have happened then,” he said. “If they’d done that, I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing now. I’d have been a watchmaker or something.”

The Ueltschis settled in Kentucky.

“The Swiss who came from Bern, Switzerland, had a little colony up in Kentucky,” he said. “They named that little village Bernstadt.”

Later, his grandfather moved his family to a diary farm in Franklin County. The Ueltschis settled in the rural community of Benson Valley, Ky., not too far from Frankfort, the state capital.

On May 15, 1917, Albert Lee Ueltschi was born to Robert and Lena Ueltschi, on his grandparents’ farm. Eventually, his father left the farm to work as an engineer, installing lights on Mississippi riverboats. When Grandfather Ueltschi died, his three sons took over the farm. Al Ueltschi grew up there with his four brothers and two sisters.

“It was an interesting life, but it was tough,” said Ueltschi, the youngest sibling. “My father and mother were terrific. The only thing we didn’t have was money.”

A.L. “Al” Ueltschi, founder of FlightSafety International, says the best safety device on any aircraft is a well-trained pilot.

He soon realized that life on a farm, even with so many to share the tasks, is “rigorous.” Each day, the cows needed to be milked. Then Ueltschi and his brothers would ride into Frankfort to deliver the bottles of milk door-to-door to customers.

“We’d get a nickel a quart,” he said. “It was tough to do all this work and then only get a nickel.”

The empty bottles were brought home and cleaned for reuse. After they’d accomplished all that, they cleaned the stalls and then went to school.

After four years in a single-room schoolhouse in Choateville, Ky., Ueltschi transferred to a school in Frankfort. Nothing he learned in school was as fascinating as the stories he loved to read about the pilots of the day and the aircraft they flew.

“I loved airplanes from the very beginning,” he said. “From when I was 5 years old, on the farm, I used to tell my dad I liked airplanes and that I wanted to fly.”

Ueltschi will never forget the excitement he felt when Charles Lindbergh made his historic flight across the Atlantic in 1927. He listened intently to the radio for any report on the flight. As he listened to the announcer tell how thousands of Frenchmen had carried the aviator off the field after he landed in Paris, he knew he’d be a pilot.

“I’d follow my father around and tell him what I was going to do,” he said. “He probably thought I was a little nuts, but he never discouraged me. But when Lindbergh flew the Atlantic, I told him, ‘Now, dad, I’m really going to be a pilot.’ He said, ‘Al, you are.’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ He said, ‘You pile that cow manure over here and pile it over there; you’re a pile-it.'”

Ueltschi was even more determined to fly after he started high school in Frankfort. But he had no idea how he would afford lessons. Then the young entrepreneur had an idea.

“A little hamburger shop, White Castle, was near the high school,” Ueltschi said. “I saw those hamburgers in there for a nickel and I thought, ‘If you can sell a hamburger for a nickel, it would be a heck of a lot easier to do that than to milk the cow and deliver the milk for a nickel a quart. So I started a little restaurant.”

A building owner generously allowed the 16-year-old to use a corner of his building. With aviation on his mind, he called his hamburger stand the Little Hawk Restaurant.

“It was a little hole in the wall,” he said. “He let me put seven stools in there, a grill and a little counter. We were selling hamburgers for a nickel and Coke for a nickel.”

Although he had lots of customers, he wasn’t making any money.

“Finally I said, ‘I can’t make it on a nickel.’ I raised the rate to 10 cents,” Ueltschi remembered. “If they bought a dozen, I gave them a volume discount. I’d give them 12 for a dollar.”

Soon, he hired school friends to run other hamburger stands. Now that he was making a little money, he was able to take flying lessons, in an OX-5-powered Waco based at a grass-strip airport near Lexington. After soloing at the age of 16, he dreamed of buying his own aircraft. When he was 18, and nearing the end of high school, the hamburger business helped in a further, unexpected way.

“The president of the bank in Frankfort—Farmers Bank—used to come down and eat my hamburgers,” Ueltschi said. “He was a heck of a nice guy. I used to talk to him, and I told him I was learning to fly and about all these dreams I had. I told him my only problem was that I could sure get going faster and do what I had to if I had an airplane. He said, ‘How much money is it going to take?’ I told him about a great airplane I could buy for $3,500. He loaned me the money.”

The aircraft Ueltschi bought to begin his barnstorming days was an open-cockpit Waco 10.

“The engine in it was an OX5,” he said. “It was liquid cooled. It wasn’t one of these modern engines. It was out of one of the old Jennies they had in WWI. You could fly it from the backseat.”

Ueltschi based his Waco 10 at a farm on Georgetown Pike in Lexington, on a flat grassy section he declared an airport. He passed out flyers to attract business for his Frankfort Flying Service. He continued to sell hamburgers after school during the week, but on weekends, he gave flying lessons or took people for rides. He charged adults a dollar and children 50 cents for a ride that lasted about three minutes.

Although he had little interest in college, Ueltschi’s parents wanted him to get a degree, so he enrolled as a freshman at the University of Kentucky.

“I went there for a little bit, but I wasn’t interested at all in reading about ancient history,” he said. “The airport was right near the university. I hardly spent any time at all at college. People say, ‘You’re a dropout.’ No, I’m not a dropout; I hardly even ‘dropped in.’ I never graduated from college. Bill Gates and I are two losers.”

Ueltschi continued to give rides and lessons.

“I was out flying pastures,” he said. “No airports were around. I’d put on an air show, to bring people out to these open fields. I’d say, ‘Come out to Black’s farm’—or somebody else’s farm—’because we’re going to put on an air show.’ I’d do all kinds of crazy things. I was hot stuff; I had white coveralls, helmet and goggles. People would come up to me after I’d put on an air show, and say, ‘What’s the most hazardous part of flying?’ I’d look them straight in the eye and say, ‘Slow, painful starvation.’ But it was a lot of fun.”

He struck up friendships with other barnstormers, including Joe Mackey, who later founded Mackey Airlines in Florida, and Mike Murphy, who became the aviation manager for Marathon Oil’s flight department. He credits those “hell raisers” for teaching him how to do “all kinds of aerobatics.” Sometimes the three men put on shows together, doing formation flying, low-level aerobatics, ribbon cuts and parachute jumps. But eventually, Ueltschi decided it was time for a change.

A lack of funds was one of the reasons he readily accepted when George Wedekind, president of Queen City Flying Service, offered him a job in Cincinnati, Ohio. Although it was steady work, and he flew almost every day, he still dreamed of flying “bigger airplanes” for an airline. So, after logging about 2,000 hours of flying time, he applied with various carriers.

In 1941, while most other carriers were struggling to maintain service between a few cities around the country, Pan American Airway was flying scheduled service to the far corners of the world. According to Ueltschi, Pan Am’s Clippers were the “most modern, luxurious and magnificent flying machines in the sky,” and its flight crews “were the most experienced and the most respected in all of aviation.” The whole package appealed immensely to Ueltschi.

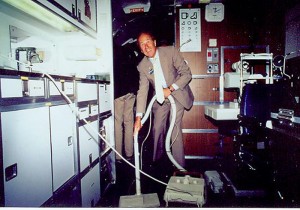

Al Ueltschi, shown in the DC-10 Flying Eye Hospital’s audiovisual studio, serves as chairman of ORBIS International.

But when Northeast Airlines, at the bottom of his list, gave him an offer, he drove to Boston and began training. Immediately after that, a letter arrived from Pan Am. Soon, he was in his car driving toward Miami, for a successful interview that would take place at the airline’s base at Dinner Key, in Biscayne Bay.

Pan Am

Ueltschi described himself as “a general assignment pilot” for Pan Am. After working in the training department for a while, he crewed briefly in the airline’s “flying boats.” He was also assigned to Pan Am’s “air ferries,” before being transferred to Brownsville, Texas, the airline’s principal base for Central and South American operations.

Fortune smiled on him again, when he was told to go to Colombia to pick up a twin-engine Lockheed 10A Electra that was to be converted to an executive aircraft. Ueltschi became the aircraft’s pilot fulltime after the modifications were completed. He would be flying for Juan Terry Trippe, the founder and CEO of Pan Am. Ueltschi had huge respect for the man who had started Pan Am in his twenties and was to become his mentor.

“He was one of the greatest men I ever knew,” he said.

In Trippe, Ueltschi saw a man with great character, intelligence and insight, as well as tenacity, wisdom, business savvy and a deep understanding of “aviation’s true international potential.” He also would come to admire his “canny politicking and willingness to take huge risks.” Those combined traits, Ueltschi said, enabled Trippe to build “the greatest airline that ever was” in just a dozen years.

Trippe’s mode of transportation might have seemed strange, but Ueltschi explained that while a passenger could fly Pan Am to “the ends of the Earth,” getting to major cities such as Chicago, Dallas or Washington, D.C. wasn’t so easy. Although the airline was America’s only international carrier, regulators denied it any domestic routes. That meant that when Trippe traveled around the country, he needed his own private plane. Later, he had other reasons to fly anonymously around the globe.

“Mr. Trippe wanted to fly around to different parts of the world,” Ueltschi explained. “If he got on an airline, everybody knew where he was going. He didn’t want everybody to know that, because when he went places, they’d follow him. It was just like today; many corporations have their own airplanes, so they can go where and when they want. It has a lot of advantages.”

Initially, Ueltschi’s assignment as Trippe’s personal pilot was supposed to be for six months, but that wouldn’t be the case. His tour lasted until he retired from Pan Am, 25 years later. After the Electra, Ueltschi flew different aircraft for Trippe, including a DC-3 and a converted B-23 bomber. The final aircraft he flew for Trippe was a Falcon 20.

Trippe wasn’t the only important executive Ueltschi flew.

“General Eisenhower came back after World War II ended, before he ran for president,” he said. “I flew him out to Wisconsin. I used to fly all these dignitaries around.”

Other prominent passengers included Gen. George C. Marshall and Francis Cardinal Spellman. Washington D.C. was one of their more frequent destinations for business meetings, and members of Congress were among Ueltschi’s regular passengers.

Ueltschi valued his time spent with Trippe, but was also fortunate to be introduced to Trippe’s many companions, who invited him along on some of their excursions. One of those companions was financier Bernard Baruch, whose advice on business and finance was highly valued by several U.S. presidents. Often after Ueltschi flew Baruch to his plantation in South Carolina, he would remain as his guest for several days.

FlightSafety’s humble beginnings

It didn’t take long for Ueltschi to come to believe that Pan Am’s approach to flying was superior.

“Pan Am had a great training program,” he said.

For that, he credited Andy Priester, Pan Am’s head of operations, who “demanded precision.” He said that pilot training at Pan Am was rigorous, exacting and never-ending. While waiting at fixed based operations around the country, though, and when communing with other business aviation pilots, he didn’t notice the same diligence.

“When WWII ended, a lot of airplanes became surplus,” he said. “Companies were buying these surplus airplanes—DC-3s, Lockheed Hudsons, Lodestars and aircraft like that. But the pilots coming back from the war hadn’t gone through the kind of training the airlines provided.”

When airline pilots, who were used to operating airplanes “low and slow,” transitioned to pressurized, high-performance aircraft entering the commercial fleet, Ueltschi knew they were up to the challenge. He was assigned to help older Pan Am pilots transition to DC-6s and Constellations.

Although the government required airline pilots to demonstrate proficiency in training at least once every six months, no similar requirement was in place for business aviation pilots. Ueltschi was correct in assuming that as aircraft advanced in technology, those pilots would also have a problem transitioning.

Even if corporate pilots wanted to do transition or proficiency training, they were on their own, because no training organization was available. Ueltschi saw possibilities in giving corporate pilots a training system similar to what the airlines had. His boss was one of the first people he told about his idea.

“I told him, ‘Safety’s the most important thing!'” he recalled. “Your life is the most important thing you have, and if you’re flying an airplane, you have to be sure you do it right.”

Ueltschi recalled one particularly vivid account of “doing it wrong.” Back in 1940, when he was 23 and working as chief pilot for Queen City Flying Service, one of the assignments he liked most was conducting aerobatic standardization courses for Civil Aeronautics Administration inspectors. Although seasoned pilots, few had done serious aerobatics.

He considered himself a good aerobatics pilot, and says he was a little cocky about his accomplishments and always went out of his way to give a new inspector a thorough and sometimes harrowing introductory flight. He was fond of telling the trainees to trust the equipment—especially the seatbelt. He insisted his trainee always raise both hands above his head once inverted, to hammer home the point.

During a flight on a cold winter day with an inspector-student, who was an Army Air Corps veteran, Ueltschi demonstrated a snap roll midway through the course, at 2,500 feet. After a snap roll to the inverted position, the next step was to continue flying straight and level—but upside down. The student followed Ueltschi’s lead, and although he stopped the roll correctly, the nose was too high and the plane stalled. Ueltschi showed him the maneuver again, and turned the airplane over to him. Once again, he ended the maneuver with the nose too high and the plane stalled.

After shouting into the gosport (a rubber tube that served as the intercom) for his student to follow him through once more, Ueltschi performed the maneuver again. When the student began the roll sharply, the airplane twisted onto its back. It took a few moments for Ueltschi to realize that he was no longer in the backseat of the open-cockpit Waco, but was instead falling toward a patch of Ohio farmland.

Luckily, he was wearing a parachute, so the result of his fall into a briar patch was a few minor scratches—and a heightened awareness of safety issues. He said it took a while to appreciate them, but several significant realizations came from that experience: 1) training in an airplane can be hazardous; 2) when the unexpected occurs, take appropriate action in a timely fashion; 3) if at all possible, be lucky.

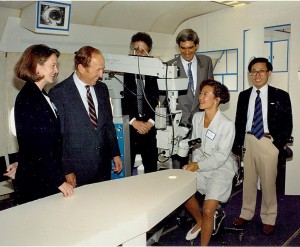

Al Ueltschi visits with former President George Bush and Eleanor McCollum outside the Flying Eye Hospital.

Trippe knew training was important, and wholeheartedly agreed that Ueltschi was on to something. Ueltschi also bounced his idea off Baruch, who was more cautious, frankly saying Ueltschi had as much to lose as could be gained. Baruch advised him to keep his job at Pan Am while embarking on this new venture. Ueltschi thought it was good advice.

“I had four kids,” he said. “I had to send them to school, and I had to make a living. I told Mr. Trippe what I wanted to do, and he gave me permission to do it (and still fly for him).”

In 1951, Ueltschi took a $15,000 mortgage on his house and started FlightSafety, on the third floor of LaGuardia Airport’s Marine Air Terminal, across from Pan Am’s operations building and the hangar that housed Trippe’s airplane.

“I had a little office there,” he said. “I had a desk and one fulltime employee.”

What he didn’t have was an intricate strategy.

“I didn’t have a big plan,” he said. “It started out with an idea, and it just kind of grew. I saw what Pan Am was doing. I saw a need and had to find a way to fill the need.”

Although his strategy wasn’t mapped out, Ueltschi was well aware of his mission.

“Our mission is to train every pilot, so that no matter what happens, that pilot is prepared to handle the situation,” he said.

Ueltschi himself didn’t instruct. His job was to manage operations and find customers.

“I was running the company,” he said. “I used some of the Pan Am instructors when we got business—if we got business. I paid them by the hour. I didn’t have anybody on the payroll for a while, until I built up the business.”

Ueltschi’s secretary’s priority was typing letter after letter to solicit business. On Ueltschi’s time off from Pan Am, he worked on building FlightSafety. At first, however, “for a frighteningly long time,” each day was a challenge. He said most of the corporate pilots he approached had a single mindset: “I already know how to fly just fine, thank you, so why do I need advice?”

Ueltschi agreed they were “fine pilots,” but tried to convince them that FlightSafety could help point out ways they could work better as a team, and that a few sessions in the procedures trainers would help sharpen their instrument-flying skills. For the most part, his pitch was unsuccessful.

Fortunately, however, he had sold Trippe on his business. In turn, Trippe urged his friends, many of whom were CEOs of companies that operated airplanes, to have their pilots trained at FlightSafety. Slowly, the customers came.

“It grew from there,” Ueltschi said. “It just kept growing.”

Early training

In FlightSafety’s early days, training was a little different than it is today.

“We had no simulators, so we did all the flying in the airplane,” he said. “You’d just ride in the airplane, and you’d shut the engines down on takeoff. You’d do all these crazy things.”

That training most often occurred in customers’ airplanes and, since LaGuardia wasn’t nearly as busy in the 1950s, right outside FlightSafety’s office. Ueltschi was familiar with simulators, however.

Al Ueltschi (second from left) praise the more than 350 ophthalmologists who donate time to Project ORBIS.

“We had some of the first simulators at Pan Am,” he said. “But they weren’t real simulators; they were the old-fashioned kind. They were almost like a simulator. Now, with the technology, you can do everything in the simulators you can do in an airplane—and it’s under controlled conditions. You can teach pilots and crews how to handle all emergencies, so that no matter what happens, they’re prepared. They won’t be surprised when it happens. It’s a worthwhile thing to do.”

Ueltschi voices his thankfulness for luck again—this time, because he was “born at the right time and in the right place.” That timing meant he would be ready to take advantage of the new technology as it came along.

In FlightSafety’s early days, the company rented Link Trainers from United, which had a hangar at LaGuardia. Later on, Ueltschi acquired four used Links from TWA, as well as some Dehmel Duplicators, a real instrument trainer manufactured by the Curtiss-Wright Company that was much more advanced than the Link. Later, FlightSafety became Ed Link’s first customer for the Translator, a piston twin machine similar to a Convair, which was an even more capable trainer.

That first simulator, which they acquired in 1955, cost $150,000. Within five years of simulator delivery, a nucleus of flight departments, including those at Eastman Kodak, Coca-Cola, National Dairies, Gulf Oil and Olin Mathieson, advanced nearly $70,000 to guarantee training for their pilots.

That second-generation Link helped advance FlightSafety to a new level of service. After four years of struggling, the first annual report signed by Price Waterhouse in 1955 listed total revenues of $177,096.34. Expenses came to $176,818.93. FlightSafety had made a net profit of $277.41.

“We’ve been profitable every year since,” Ueltschi said.

In the early 1960s, turbine-powered aircraft such as the JetStar, Sabreliner, Gulfstream and Learjet began changing the face of business aviation. Ueltschi said that in general, pilots reacted to these sophisticated, high-altitude, high-speed jets in one of two ways.

One group, ill at ease in jets, distrusted them completely and had an aversion to flying anything without propellers. The second group saw very little difference in flying an aircraft with turbojets or one with pistons and props. He said both groups had their share of problems, and the evidence was a series of unfortunate accidents involving “new kinds of airplane killers such as Mach tuck and overspeed.”

The dawn of turbine-powered aircraft signified a definite increase in business at FlightSafety. Pilots, owners and insurers all realized that the best place to master this new breed of business aircraft was inside a simulator. The company soon began adding real simulators and using type-specific machines instead of generic trainers, and real cockpits were united with analog computers and hydraulic-motion bases.

“Sabreliner pilots flew Sabreliner simulators; King Air pilots flew King Air simulators,” Ueltschi said. “We even converted our original Link Translator into a Gulfstream I.”

Ueltschi said that while those simulators were a major improvement, they were far from perfect. True simulation began with the arrival of the digital processor.

“When simulators were mated with these new computers, the resulting fidelity in handling, visuals, motion, instrument readouts, sound and feel reached unprecedented levels,” he said.

Pan Am Business Jets

Volunteer DC-10 pilots from FedEx Express and United Airlines fly the Flying Eye Hospital to and from program sites.

While FlightSafety was taking off, Ueltschi continued to enjoy his ties with Pan Am. Trippe, intent on having the “everything aviation company,” had his eye on business aviation as well, and believed Pan Am should market and support a brand of business jets.

Charles Lindbergh, who served as one of Trippe’s special advisers, was particularly attracted to the Mystere jet, made by Dassault in France. While Pan Am evaluated the aircraft, Ueltschi had the chance to room with his boyhood hero in Bordeaux. Ueltschi had the honor of flying with Lindbergh several times, and the two men became friends.

In 1966, Trippe made a deal with Marcel Dassault, to form a new division called Pan Am Business Jets. The division would handle North American marketing for the French airplane, which was named the Falcon Jet. Ueltschi persuaded Trippe to include pilot and maintenance technician training at FlightSafety as part of the purchase price of every new Falcon. He said that deal established FlightSafety’s simulator training as an integral part of modern business aircraft operation.

“FlightSafety training became the standard,” Ueltschi said.

In the early 1970s, Learjet agreed to the same kind of arrangement. Other manufacturers would also designate FlightSafety their official training company, with Gulfstream, Sabre, JetStar and Jet Commander among the earliest.

Moving forward

In 1968, Ueltschi, 50, decided he needed to take FlightSafety public. Simulators were a vital part of the company’s future, but they were expensive and required a big investment. He also decided to retire from Pam Am, believing it would be unsuitable for the CEO of a public company to be employed by another company. He said leaving Pan Am, after 26 years, was both one of the hardest and one of the most exciting moments of his career.

“After I left Pan Am, I took a paycheck out of FlightSafety for the first time, after working there for 17 years for nothing,” he said.

As different manufacturers designated FlightSafety their official training company, dedicated training centers were built at or adjacent to the manufacturers’ factories and service centers.

“That way, pilots could train as their aircraft were being built or serviced,” Ueltschi said. “They would also have ready access to the people most familiar with their airplanes—the people who designed and built them.”

FlightSafety training centers sprang up in Kansas, Georgia, Texas, Missouri, Florida and New Jersey. As more companies came to understand the transportation advantages of business aviation, the industry rapidly expanded, and FlightSafety flourished.

“The executives who rode in these machines expected a level of safety equal to or surpassing that provided by the airlines,” Ueltschi said. “FlightSafety was the only company with the equipment, staff and experience to provide the training necessary to assure that level of pilot competence. We were in the right place at the right time with the right stuff.”

By 1972, the company had doubled the 1967 gross revenue figure of a little over $4 million. Five years later, that figure would again double. Instead of squandering the profits, Ueltschi said money was poured back into operations and facilities, to make sure customers had the most sophisticated, complete and convenient training experience possible.

By 1978, FlightSafety listed 1,200 business aircraft operators and airlines as clients, and was training thousands of professional pilots at 18 different learning centers in the United States, Canada and Europe. The company operated 30 simulators. Although they would continue to buy simulators from other manufacturers, the need was so strong that they bought a simulator manufacturer in Tulsa, Okla., and formed FlightSafety’s Simulation Systems Division. FlightSafety began producing some of the most advanced and sophisticated flight simulators anywhere, for use in its centers and for sale to airlines and operators throughout the world.

Worldwide, 37 million people are blind—28 million of those unnecessarily. ORBIS strives to eliminate avoidable blindness and restore sight in the developing world, which is home to at least 90 percent of the world’s blind and visually impaired.

By 1996, FlightSafety had become the authorized training company for about 20 different aircraft manufacturers, and was conducting initial and recurrent training for a number of domestic and international carriers. The company’s simulator fleet was the largest in the world. FlightSafety operated more than 100 flight simulators for more than 50 different types of aircraft. More than 50,000 pilots and maintenance technicians annually trained with the company at three dozen learning centers around the world. Annual revenues were $325 million.

Ueltschi said that for a while, they were busy but barely made money. At that time, FlightSafety had primary flight training centers at five different airports and operated more than 100 airplanes. He said they fixed the problem by limiting primary flight training to only one location, the FlightSafety Academy in Vero Beach, Fla., dedicated exclusively to training future professional pilots. The academy has become one of the premier primary schools in the world.

Believing that helping to educate and mold youth is a priority, FlightSafety also has a relationship with Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. An Advanced Flight Simulation Center on the Daytona Beach campus, created through a joint venture between the university and FlightSafety, now houses an FAA-certified Level-D Beech 1900D full-motion simulator that provides a level of training not available at any other university in the world.

FlightSafety Simulation

FlightSafety Simulation is comprised of Simulation Systems Division and Visual Simulation Systems. SSD, headquartered in Broken Arrow, Okla., designs, manufacturers and fully supports full flight simulators and simulation-based training software and devices for clients worldwide. VSS, based in St. Louis, Mo., develops advanced imaging systems, including SkyLight projectors and the VITAL series of visuals.

Over the past 20 years, FlightSafety Simulation has served all branches of the U.S. armed forces, as well as foreign military, by training pilots, providing state-of-the-art full flight simulators and flight training devices, as well as performing upgrades to existing training equipment. FlightSafety Simulation has built, or is currently building, a number of military simulators, including C-17, T-6A Texan II, MV-22, CV-22, TH-67, UH-60A/L, AH-1, UH-1, C-12, OH-58D, U-21 and C-130.

FlightSafety also trains law enforcement specialists from the U.S. and abroad. The company has trained FAA and DEA pilots, as well as pilots who fly aircraft assigned to the White House.

MarineSafety

Believing their expertise in hands-on, simulator-based training would work well in other fields, in the mid-1970s, Ueltschi established MarineSafety to provide training for merchant marine and surface Navy officers. MarineSafety training centers are located in the United States and Europe. Ueltschi said it’s still hands-on training, but instead of aerodynamics, it’s hazard-dynamics.

Although he considers himself lucky on many levels, he says he’s been luckiest where it comes to picking the right people, from instructors, to technical staff and courseware creators, to company executives.

“It doesn’t matter how technically advanced the simulators, how colorful the textbooks or how comfy the learning centers are, FlightSafety is first and foremost a training company where knowledge is transferred from one person to another,” he said. “If the instructors and managers aren’t first rate, the training experience will be unsatisfactory, and the customers won’t return. It’s that simple.”

What will happen when I exit the stage?

In the 1990s, Ueltschi became concerned that once he “exited the stage,” FlightSafety—the company he and others had built so carefully and so well—could fall into the hands of an outsider, be taken over and possibly be parceled out. He didn’t want that to happen, but he wasn’t sure what to do about it.

“We were doing pretty well,” he said. “I went public—over the counter—and then we went to the American Exchange, and from there to the New York Stock Exchange. We were making good money—not too much, but we were doing well. Of course, we had to report all of it in earnings and so forth. A lot of big companies wanted to buy us. I didn’t want to sell it, because I’d seen what happened when big companies buy a small company. The first thing they do is change everything—put their name on it and put in new management and everything. I had a good little company there, and I wanted to be sure that we kept our mission going. If I had sold it to some of these big companies, we wouldn’t have been in business. I felt obligated to the employees, as well as to the shareholders and to the people we were training.”

His concern turned to relief when Warren Buffett requested a meeting.

“I said, ‘Sure, we’re a public company, and we’ll talk to anybody,'” Ueltschi said.

Although Buffett had sent his pilots to FlightSafety for training, the two never met, until one afternoon in late 1996.

“He and I had a meeting there in New York, in a little room with one table,” he recalled. “He had a hamburger and a Cherry Coke, and I had a hamburger and a Coke, and we put a deal together.”

Buffett told Ueltschi he wanted FlightSafety to be a part of Berkshire Hathaway, but that it would remain independently operated, continuing on the same course of business, and run by the same people as before.

“I knew that if Warren Buffett had the company, it would continue its mission,” he said. “After we made our agreement, he went home and wrote it all up. Of course, being a New York Stock Exchange company, we had to get a fairness opinion. Some people said, ‘You should have gotten more money.’ I said, ‘We were a public company, and I had a fiduciary responsibility.’ We had no breakup fee or any of that at all—just straight stuff. We didn’t negotiate at all, just made the deal. He didn’t even do due diligence on the company, because he had been reading my annual reports, and he knew a lot about the company. He talked to my customers, and he knew what was going on.”

The $1.5 billion deal, for which Ueltschi received Berkshire Hathaway stock, was completed in late December 1996. Ueltschi remained president of FlightSafety until November 2003, when he assumed the title of chairman. At that time, Bruce Whitman became president of the company. Whitman, who joined FlightSafety in 1961, formerly served as executive vice president.

Today, FlightSafety has more than 1,500 instructors and offers more than 3,000 courses for pilots, maintenance technicians, flight attendants and dispatchers.

FlightSafety presently has a network of 43 Learning Centers in the U.S., Canada, France and the U.K. The company’s fleet of more than 230 FAA-certified flight simulators—from piston twins to commercial airlines, helicopters and large military transports—is the world’s largest. Several of the centers are equipped with facilities providing type-specific training for pilots of most light aircraft widely used today.

Since 1978, FlightSafety has produced nearly 400 full flight simulators. The company currently provides engineering and logistic support for approximately 350 simulators worldwide.

ORBIS

It was through Juan Trippe that Ueltschi became involved with ORBIS, a nonprofit organization that strives to eliminate avoidable blindness and restore sight in the developing world, home to 90 percent of the world’s blind. The founders of ORBIS chose the name because it aptly captured their mission and global, long-term goal. The word was drawn from both the Greek and Latin languages. In Greek, orbis means “of the eye.” In Latin, it means “around the world.”

One day in the early 1970s, Trippe asked Ueltschi to have lunch with him and his daughter, Betsy Trippe DeVecchi.

“I had lunch with them and David Paton, who was one of the top ophthalmologists at Baylor School of Medicine in Houston,” Ueltschi recalled. “He and his father were both ophthalmologists. They had been to a lot of these developing areas of the world, and seen all the blind people. He had an idea that if he put a hospital in an airplane, he could get into these different parts of the world.”

More than 37 million people worldwide are blind, but 75 percent of all blindness is preventable or curable with existing eye care resources and medical interventions. Paton’s interest in international ophthalmology and the problems of eye care, in both developed and developing nations, led him to travel extensively in teaching capacities throughout the globe.

During his travels, he observed that the high costs of tuition, international travel and accommodations prohibited the majority of doctors in developing countries from participating in overseas training programs. Even when they could afford to study abroad, their opportunities for direct clinical experience were limited, because strict licensing laws often prevented them from performing surgery. Paton’s solution was a mobile teaching eye hospital. With a fully equipped airplane, American doctors trained in the latest techniques could teach doctors in developing countries their surgical knowledge and skills, through hands-on training and lectures.

Trippe thought Ueltschi would be the perfect person to help Paton with his cause.

“He said, ‘Skipper, do you think you could help this guy out?’ I said, ‘Well, I don’t know; I’ll go down and see what’s going on.’ I went to Houston and they were doing a good job,” Ueltschi recalled. “Betsy was running things. She was great.”

Other people, including philanthropists, doctors and aviators, soon became heavily involved, such as L.F. McCollum, the president of Conoco. Project ORBIS was officially established in 1973. Initially, the biggest job was finding an aircraft.

“We went around the country to get one,” Ueltschi said. “After going to a lot of airplane manufacturers and airlines, we finally wound up at United Airlines. Eddie Carlson was the chairman of United. He heard about the program and said, ‘It sounds pretty good.’ He told Dick Ferris, who was United’s president at that time, ‘Dick, give these guys an airplane.'”

The aircraft they eventually received was far from pristine.

“It was an old DC-8,” Ueltschi said. “It was one of the oldest ones they had, and it had been taken out of service. It was leaking fuel out of the wings and everything else. Eddie told Dick, ‘Now that you’re giving them this airplane, make them file a statement that they won’t sell it, and that they have enough money to fix it up.’ We really didn’t have the money to fix it up, but we knew we could get it, so we signed it up.”

With a grant from USAID and funds from private donors, extensive modifications were made to the DC-8, to convert it into a fully functional, teaching eye hospital. Staffed by a highly skilled team of ophthalmologists, anesthesiologists, nurses and biomedical technicians, the ORBIS DC-8 Flying Eye Hospital took off from Houston in the spring of 1982, for its first program, in Panama.

In the next few years, ORBIS programs were initiated in critical areas including Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, China, Turkey, Colombia, Jamaica, Uruguay, Paraguay, Costa Rica, Morocco, Tunisia, Jordan, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Cyrus, Swaziland, Malawi, Botswana and Kenya. In 1985, ORBIS conducted its first week-long hospital-based training program for eye surgeons. The focus of the programs quickly spread beyond the surgical element of saving sight, to offering training opportunities in biomedical engineering, nursing, community eye care and other support areas critical to ophthalmology.

A DC-10, with more than twice the interior space, replaced the DC-8 in 1992. ORBIS received a total of $14 million in donations, in order to make the purchase. Of that $14 million, Ueltschi donated $6 million; Y.C. Yo, a Hong Kong businessman, donated $7 million, and an anonymous donor donated the remaining $1 million. The total cost to transform the former DC-10 passenger plane into a fully equipped eye hospital was $15 million. Including the design phase, the total project took two years to complete.

In 1994, the DC-8 was formally retired. It’s now on display at the Aerospace Museum in Beijing, China. The DC-10’s inaugural mission was to Beijing that year.

The success of hospital-based programs encouraged ORBIS to expand its efforts to help countries with long-term blindness prevention. In 1998, ORBIS established the first of five permanent programs, in Bangladesh, China, Ethiopia, India and Vietnam. The centers enable ORBIS staff and volunteers to work directly with national medical and ophthalmology communities, to develop programs, open eye banks and establish eye care facilities, widen training, and conduct outreach in rural and poor urban areas.

Ueltschi has been on many of the missions, including the DC-10’s inaugural mission to China.

“I went to Russia when they still had the Iron Curtain,” he said. “This airplane’s been to more than 70 countries. Just recently, we went to Libya.”

Ueltschi said that ORBIS is about education and hands-on training, although its focus is medical education.

“Years ago, when we first started out, we’d go into a country, and the first thing we’d do is go to the butcher shop and buy a bunch of pigs’ eyes. We’d put them in a bucket with some ice,” he said. “Then the doctors would practice operating. They’re not like human eyes, but that was our wet lab. Now we have simulators, just like we have for the airplanes. Doctors love it; it feels just like operating on a human being.”

The simulators can be moved into the hospitals.

“We can go into hospitals, and we help set up hospitals in these different parts of the world,” he said.

Along the way, ORBIS has had help from many sources. FedEx is one of those partners.

“FedEx is a big part of this,” Ueltschi said. “Fred Smith is a wonderful guy. He’s done so many things for us at ORBIS. When we got that DC-10, we had it all fixed up, and then we lost an engine on one of the first missions. I called all these places, because we had to overhaul the engine. Everybody wanted $100,000 to sign a contract just to use an engine, and then, more money per cycle. We couldn’t afford that.

“I finally called Fred Smith. I said, ‘Fred, we have a problem and we need this engine. Could we borrow an engine from you for 30 days or a couple of months?’ I told him how much money everyone wanted for it, and that they wanted me to sign a contract. Fred said, ‘Let me look. I’ll call you back.’ He looked and he had one. He called me back, and he said, ‘I have one; we’ll let you have it. But you’ll have to sign a contract.’ Then he said, ‘Let me think; it will be ten dollars.’ He had his people take the engine off; he had it overhauled, and put it back on the airplane. I bet it cost $1 million. And he did the whole thing.”

Volunteer DC-10 pilots from FedEx Express and United Airlines fly the Flying Eye Hospital from site to site. Until 2001, when United retired its fleet of DC-10s, the airline held the lead role in maintaining the Flying Eye Hospital. FedEx has since taken over as the primary aviation sponsor. In addition to providing pilots, recurrent pilot training and a fulltime aircraft maintenance technician, FedEx ships urgently needed medical supplies to ORBIS program sites at no charge.

Ueltschi points out that the ophthalmologists also donate their time.

“We have 350 of the finest ophthalmologists in the world, and we don’t pay them either,” he said. “The money we get all goes toward our mission of reducing blindness and suffering and to saving sight. We don’t pay the directors any director fees. They have to give or get—give it, get it, or get off.”

Many individuals and companies have pitched in to help the cause.

“We’ve had a lot of great people helping us, like Alcon,” Ueltschi said. “I’d bet they’ve given us $5 million. Not all in money; a lot of it is in stuff. Pfizer and a lot of these companies have helped us a lot to try to reduce blindness. A lot of people are involved in it. It’s not one person. It’s an organization.”

Honors

In February 2006, Ueltschi received the ORBIS Lifetime Achievement Award. But he said he wouldn’t accept it for himself.

“I accepted this for the organization,” he said. “I’m not a doctor; I was just a dumb pilot. These doctors are doing it. This organization is doing it. That’s what it’s all about.”

Ueltschi was the recipient of the 1991 National Business Aircraft Association’s Award for Meritorious Service to Aviation. That same year, he received the Federal Aviation Administration’s Award for Extraordinary Service. In 1994, the Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy was presented to Ueltschi, and Aviation Week magazine awarded its Laurel Award to him in 1995, citing his lifelong achievement in aviation.

In July 2001, FlightSafety’s 50th anniversary, Ueltschi was enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame, following in the footsteps of Lindbergh, who was inducted in 1967, and Trippe, who was a 1970 inductee. The National Aeronautic Association presented Ueltschi with its Elder Statesman Award in November 2001, and a month later, he received the NBAA’s American Spirit Award. The Aero Club of New England presented him with its Godfrey Cabot Award in June 2003, citing Ueltschi’s “unique, significant and unparalleled contributions to foster aviation.” Most recently, Ueltschi received the Wings Club’s 2006 Distinguished Achievement Award. He was honored at the Wings Clubs’ 64th Annual Dinner-Dance, held Oct. 27 at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City. More than 1,000 industry leaders attended the event.

This article is based on a personal interview with A.L. Ueltschi, supplemented by a Wings Club Sight lecture he gave in 1997, which later became the foundation for the book, “The History & Future of FlightSafety International.” For more information about FlightSafety, visit [http://www.flightsafety.com]. For more information about ORBIS, visit [http://www.orbis.org].