By Di Freeze

As a group of people talked over coffee at the Mojave Inn, in Mojave, Calif., in late 1980, Burt Rutan doodled on a napkin. He was drawing an aircraft he thought could make a nonstop, un-refueled flight around the world—one of the last major milestones to be recognized as a significant event in aviation.

His older brother, Dick Rutan, who had been highly decorated for his F-100 flights in Vietnam, and who worked for the aircraft designer as chief test pilot and production manager at Rutan Aircraft Factory, immediately voiced an interest in building and flying the aircraft. Jeana Yeager, the pilot’s girlfriend, jumped at the chance to be his teammate.

The aircraft could be built using carbon fiber, a material half the weight and five times stronger than steel. Ultimately named Voyager, the 939-pound, twin-boom aircraft would be the largest composite plane ever built.

Major industry sponsorship didn’t come through for the flight that would cost more than $2 million, but members of the Voyager Impressive People Club would provide monetary and emotional support. And talented people showed up at Mojave Airport, volunteering their time to the project. Bruce Evans was one of those volunteers. He had composite material experience and eventually became the project’s crew chief.

Companies did step forward to help. They included Hercules, which provided carbon fiber, and King Radio, which supplied an Omega navigation system, radios, radar and an autopilot. Although other engines were used in testing, the aircraft’s main cruise engine for the world flight would be a Teledyne Continental liquid-cooled IOL 200. The front engine would be a 0-240.

Work on Voyager began in 1982. In 1984, after outgrowing the back room at RAF, Hangar 77 at Mojave became Voyager’s home.

Dick Rutan took Voyager for her maiden flight on June 22, 1984, and quickly learned that they’d have to pay the price for an aircraft optimized for range, which was virtually a “flying fuel tank” (16 fuel tanks in the wings and fuselage fed into a common fuselage feed tank). It wouldn’t be easy to control this “weak and frail” plane. His second flight revealed that in thermals, Voyager’s long, thin wings flailed, flexing and bending, causing the aircraft to sink and climb.

Although problems plagued the flight, Yeager and Rutan flew Voyager to EAA AirVenture Oshkosh in August 1984, where a quarter of a million people cheered them on, waving white kerchiefs in the air.

Weather and mechanical problems were issues—but not the only issues. As time went on, Rutan and Yeager’s relationship was often strained, in the air and on the ground. On the world flight, they would be spending many days and nights together, in a less-than-ideal environment. The cramped cabin, which would come to be known as the “torture chamber,” and the cockpit were side by side within the fuselage. The crew’s living quarters resembled a horizontal phone booth.

They forged on, and in July 1986, they set a closed-course, non-refueled, distance record. It was the first time an absolute, unlimited category aviation record had been established since World War II. In 111 hours and 44 minutes, they traveled 11,857 statute miles, breaking the Air Force’s world distance record, set by a B-52H crew and held for nearly 40 years.

At one point, that flight was interrupted with an emergency landing at Vandenberg Air Force Base. They had numerous problems with the aircraft, including a faulty prop pitch control motor, an issue with the elevator, clogged spark plugs and an encounter with flutter, the uncontrollable flapping of a control surface that could have—but, luckily, didn’t—torn an aileron or elevator loose from the airplane.

That flight proved they could go at least halfway around the world. But, could they go all the way?

Renewed energy

With growing attention for their project after the Pacific flight, and with the support from their expanding VIP club, Yeager and Rutan had renewed energy to prepare for their world flight.

As they traveled around, looking for support, three questions were most often asked. Rutan answered the first by holding up a fecal containment bags, and the second by saying, “No, Jeana isn’t related to Chuck.” As 1986 had begun to unfold, in answer to when they would take off, he had responded with a date he’d pulled out of thin air: Sept. 14. But that date had come and gone, and factors weren’t in place.

Inside Voyager, long hair could be a hazard, so before their first overnight flight, Jeana Yeager had her hair cut.

They continued making test flights, some worse than others. In later stages, at any weight above 6,500 pounds, they would take off from Edwards Air Force Base’s 15,000-foot runway. At that weight, they could no longer stay in the air using just one engine.

“We didn’t want to risk the plane, in case we lost an engine on takeoff,” Rutan explained. “On Edwards’ longer runway, in such a situation, we could abort, but not at Mojave.”

They would fly the plane to Edwards at lighter weight. Evans’ team would then fuel it up the rest of the way.

During test flights, Rutan grew to believe Voyager was a beautiful, but inherently dangerous and unsafe aircraft. Early test flights revealed a particularly troubling problem. Voyager developed an oscillating pitch and wanted to porpoise when at heavier weights, between 82 and 83 knots and while picking up thermals. In an updraft, the wings bowed, the tips went up, and the wing roots went down, carrying the fuselage with them and pitching up the nose and canard. The motion repeated and magnified, unless the pilot or autopilot was able to stop the cycle. They could take it down to 82 knots when running into thermals, but to generate enough lift to sustain its weight, Voyager would have to fly above the critical speed.

Rutan would come to fear Voyager’s “flapping” wings. Leading the wave by 90 degrees controlled the porpoising, but the pilot would have to anticipate the cycle. Because of the flapping wings and longitudinal oscillations, a pitch stability augmentation system, a special rate gyroscope for the pitch control, assisted the autopilot.

An alternator, which was supposed to last 2,000 hours, had failed; that turned out to be one of the easiest repairs. Yeager and Rutan had also smelled smoke; an earlier repair job had left an ungrounded wire that fed into a wall of epoxy.

On one final approach, Rutan overshot dramatically because of the turbulence, and on the second try, the aircraft was way too high. Voyager rolled uncontrollably from side to side, as it bounced up and down.

“How the hell are we going to fly this thing around the world, when we can’t even land at our own airport?” Rutan wondered.

On that day, after a 10-minute flight that was “agonizingly slow and sickeningly rough,” they ended up landing at Edwards. Rutan recalled that it was one of the worst approaches he’d ever made. Twenty years later, he recalled some of his fears and frustrations.

“We spent five years talking people into helping us,” he said. “I told them, ‘We’re going to fly around the world; it’s really going to be neat.’ Then, I realized the airplane was very dangerous and unstable. We were planning on going off in the world’s unpredictable weather system, with this little, fragile airplane, heavily loaded. The chances of survival were really nil, but I couldn’t get out of it. I didn’t have enough courage to tell them I was too chicken to do it. I was committed to get in the airplane and go on. I really thought I was going to die.”

Burt Rutan had suggested some fixes, and on Sept. 29, they were up in the air again, testing Voyager’s response. The designer had thought the pitch problem might be because the aircraft’s center of gravity was too far to the rear. Shifting the CG confirmed that the problem was aeroelastic—it was related to the airplane’s shape as it flexed.

They continued testing the effects of shifting CG by transferring fuel out of the aft boom tanks into the feed tank. Halfway through the process, the cockpit filled with smoke, and the airplane shook violently. Instruments came loose from the panel and the radar screen popped out. In the chase plane, Evans, Doug Shane and Jack Norris were surprised to see a prop fly past.

Voyager was experiencing another violent pitch problem. Rutan worked to get the plane under control as Yeager worked the engine controls. They were amazed to find that they hadn’t lost the engine, even with the loss of an entire prop blade.

Not knowing the condition of the back prop, which could’ve been damaged by debris, Rutan declared an emergency and received clearance to enter Edwards’ restricted area.

“We came down in a typical flameout landing pattern,” Rutan said. “We’d never landed that heavy before.”

In July 1986, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager set a closed-course, non-refueled, distance record in Voyager. It was the first time an absolute, unlimited category aviation record had been established since World War II.

As Voyager turned off at midfield, the crash wagons arrived. An examination of the aircraft revealed that the engine had broken off its mounts and was lying in the bottom of the cowl. A large hole showed where the prop had gone into the spinner.

Voyager was pushed to a parking slot next to a B-52 bomber. Fergy Fay arrived at Edwards with a prop and extension from their first overhauled Lycomings. They then set about making temporary repairs, using duct tape to repair the cowling’s holes.

Rutan and Yeager took off the next morning at dawn, using only one engine. Everyone was thankful that the prop had been lost on a test flight and not while flying over an ocean.

Besides the repairs that would need to be made, they had other worries. According to Len Snellman, their chief meteorologist, the coming months’ weather prospects were discouraging.

“The weather and possible mechanical failures were the biggest problems we had,” Rutan said. “Either one of those could cause disaster. The airplane was so frail, the weather would tear it up easily, and any kind of mechanical failure would put us in the water.”

Waiting another year might mean the loss of sponsors and volunteers.

Voyager rescue mission

The timing of the lost prop turned out to be fortuitous. The day after their return from Edwards, team members flew to the National Business Aircraft Association’s annual convention in Anaheim, Calif. The visit would serve two purposes. The team could “rally the troops” and negotiate their urgent needs with the CEOs of current or potential sponsors, who would normally be scattered around the nation.

The first stop for the “Voyager rescue mission” members was the Teledyne Continental booth, which displayed a 20-foot scale model of Voyager and featured the new line of liquid-cooled Voyager engines. The company quickly agreed to refurbish the engines at its facility in Mobile, Ala. Teledyne mechanics would rebuild the front engine, to make sure it had no damage from the prop loss, and would check the rear engine and drill it for the hydraulic prop control governors. Beech agreed to loan an aircraft to ferry the engines to Mobile and back.

TRW Hartzell agreed to manufacture metal props within 10 days, to replace the wooden props. Teledyne would then mate the new props to the refurbished engines.

The crew had originally chosen wooden props, supplied by a German company, to keep the weight down. But, they found that the constant-speed, variable-pitch Hartzell aluminum propellers were worth the additional 70 pounds. Since metal props could be more finely machined, efficiency would be better. In fact, the performance factor was three to five percent improved.

Team members were now hopeful that they were within a month or two of making the world flight.

Mission ready

Voyager was ready to take to the air again by mid-November.

During the delay, they had installed a backup autopilot and a satellite-linked global positioning system from King Radio.

The team scheduled the last test flight for the first week of December. At 8,600 pounds, Voyager took off at 85 percent of the world flight’s planned takeoff weight. The six-hour test flight was blissfully uneventful.

Voyager returned to Edwards Air Force Base on Dec. 23, 1986, after its triumphant round-the-world flight.

On the night of December 12, they declared the airplane “mission ready.” Yeager and Rutan would be relying heavily on help from mission control, located in a trailer near Hangar 77. There, Rutan and Yeager spent an hour or more each day, discussing details and running through scenarios with Larry Caskey, their mission control director.

Either Bruce Evans or Mike Melvill would always be available during the world flight. The team’s critical members also included Don Rietzke (formerly of Lockheed’s Skunk Works), the chief radioman; Jack Norris would oversee performance. Although Len Snellman would provide general weather guides, the two pilots would use radar for immediate local conditions.

An uplink that provided a 36-hour course would be updated every six hours, with information regarding tracking, altitude and weather. A downlink from the airplane would give location, fuel, engine status and the physical condition of the pilots.

Initially, Rutan and Yeager had planned to fly from west to east. However, volunteer Rich Wagoner, one of the National Weather Service’s top personnel, explained that the equatorial trade winds could be very helpful. Their course would take them southwest across the Pacific Ocean, Australia, the Indian Ocean and southern Africa. They would have to contend with the Intertropical Convergence Zone, a storm-generating belt of low pressure girdling Earth at the equator. Heading home, they would fly over the Caribbean and across Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.

As time went on, a few more changes were made to the course. Snellman planned for them to go along the top edge of the ITCZ’s wall of weather and then across the Malay Peninsula and the Indian Ocean at the latitude of Sri Lanka. But, on the way home, because of winter storms, they wouldn’t be cutting across Texas and the West. Instead, they would cross Central America and come up the West Coast.

As the pilots planned departure, a typhoon formed in the South Pacific. Snellman would steer them around it, but a typhoon meant tail winds.

Voyager landed on Runway 22 at Edwards on Saturday afternoon, Dec. 13, and parked at Runway 4. It would take Evans and his crew eight to 10 hours to fuel Voyager and prepare it for takeoff.

Although the plane’s designer had recommended a conservative takeoff weight of 9,400 pounds, Dick Rutan had convinced the crew that the plane would be fine at 9,700 pounds. The new props, and the knowledge he’d gleaned from 67 flights and 354 hours in the airplane, had prompted his decision to increase the weight by 300 pounds. They would be carrying four and a half tons of fuel, making the takeoff weight 9,694.5 pounds.

On the morning of Dec. 14, 1986, the air was calm and smooth, but Voyager’s wings were covered with a thin layer of frost. Concerned about the airflow, airmen used hot-air blowers to clear it off.

As Rutan and Yeager prepared for takeoff, Voyager’s designer and Mike and Sally Melvill climbed into a twin-engine Duchess that would serve as the chase plane. Honoring the space program’s informal tradition, Rich Hanson, of the National Aeronautical Association, handed Rutan two Confederate $10 bills and then officially sealed the canopy.

Voyager’s wings had been supported by beds, and the ground crew now eased them down. Voyager had a fuel vent system, but it worked only in flight, when the aircraft’s wings were bowed up. The wings were now bent toward the ground, and crew members had to stick their fingers into the tip vents to prevent the fuel from leaking out.

Burt Rutan, Voyager’s designer, went on to design SpaceShipOne, which won the Ansari X-Prize in 2004, and the GlobalFlyer, which completed the first solo nonstop, non-refueled flight around the world in March 2005, with Steve Fossett as pilot.

A team of 99 ground volunteers, handling everything from communications and weather to business concerns, proudly waited for takeoff. The public had begun arriving hours earlier, and people now crowded a viewing area normally used for NASA activities. Crew families, VIP club members and press were positioned on the edge of the runway. The team had also invited actor Cliff Robertson, whom they’d met at Oshkosh and who’d come out to Mojave to help on occasion, to stand at the end of one wingtip.

Rutan and Yeager were ready and waited calmly. But, they still harbored concerns and worried that the takeoff weight would once again bring on those familiar oscillations, even though bob weights had been attached to the pitch control cable inside the nosewheel well, causing the oscillations to be less extreme.

The pilots ran over the procedures and received air traffic clearance, then waited as the crew continued to rid the aircraft of frost. They watched as the engine temperatures approached the red line and knew that the aircraft was overheating. Also, the longer they waited, the less fuel they would have.

Finally, Evans cleared Rutan for takeoff, just after 8:00 a.m. Rutan released the brake, gradually pushed the throttles forward and applied left full rudder to hold them on course. Then, as speed increased, he backed off for better control. He experienced a strange pulsing, a push-and-pull lunging and shuddering he’d never felt before.

“I thought the airplane was so heavy that it might be sloshing fuel,” he said.

Voyager was almost 25 percent heavier than it had been on the last test flight. As they picked up speed, the wings bent down, bow-like. On other takeoffs, the tips had lifted quickly, but now they dragged on the pavement.

Rutan was having trouble keeping Voyager straight. At the first checkpoint, they were a knot too slow, and at the next distance marker, they were two knots below. At the third checkpoint—which was at 7,500 feet, and where their families had gathered, including parents Pop and Nell Rutan and Lee Yeager—they were four knots too slow. In earlier discussions, this had been a condition to declare an abort. But, Rutan saw more than a mile and a half of runway ahead of them and wasn’t about to stop.

“The plane was accelerating smoothly and it felt strong. I believed we had a comfortable margin, even though we were slow,” he said.

Calculations showed he could begin their rotation at 83 knots, and lift off at 87, but Rutan decided to wait until they had the full 87 knots. At the end of the runway, Evans advised they were low on airspeed. As the plane approached the 11,000-foot mark, it reached 85 knots. Rutan heard Yeager call 87 knots and eased back gently on the stick.

Voyager’s wings now bent upward, farther than ever before, and at 92 knots, the airplane lifted off, with the Beech Duchess on its wing. At last, Voyager accelerated to the target climb speed, locked on to 100 knots and began climbing. The pilots had just broken a record; they had used up all but a thousand feet of the longest runway in the world, and in doing so, had just made the longest takeoff ever from Edwards.

As they turned and came back over Edwards, Melvill notified the pilots that the wingtips had been ground away and the right winglet had failed. Rutan realized that the dragging wingtips had caused the strange surging. The team was concerned about maneuverability and worried about a possible fuel leak, since the fuel vents ran up through the winglet.

Knowing they had to get rid of the damaged wingtips, Rutan applied right rudder to sideslip the airplane, and when the winglet wouldn’t budge, he repeated the maneuver with more force. Finally, the winglet sailed free, and Voyager slowly climbed to 4,600 feet. The left winglet came loose shortly after. With the winglets gone, Rutan and Yeager wondered if they’d have the range to make it around the world, because the roughened tips would cause drag. Voyager’s designer estimated that total drag might cut range by six percent, at worst.

The pilots couldn’t dwell on the problem. As they got into coastal weather, they made some minor deviations. They neared the Pacific Ocean and knew it would soon be time to say goodbye to the Melvills and Burt Rutan, since the Duchess was approaching the edge of its range.

Heading across the ocean

On Dec. 29, 1986, President Ronald Reagan awarded the Presidential Citizen’s Medal to Burt Rutan (next to First Lady Nancy Reagan), Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager.

The Duchess banked away, and the Voyager’s crew was alone. Just off the coast, Voyager picked up good tail winds. The sun went down a few hours before they reached Hawaii.

Snellman had informed them before takeoff about a tropical storm developing in the Pacific. Named Marge, the storm was now centered on the Marshall Islands. The plan was to turn northwest as they approached Marge, then come in on its top side. If they caught enough of the pinwheel’s edge, they would swirl counterclockwise, and Marge would slingshot them forward.

Snellman’s plan was to position them between two of the pinwheel’s arms, but on day two of the flight, he realized that Marge was moving north faster than expected. On its present course toward the Philippines, Voyager would run directly into the storm. Also, a low-pressure system was moving in from the north. Between the two storms, a narrow channel formed, but threatened to close up before Voyager could reach it. Not sure of the center’s exact location, Snellman advised them to drive towards what he thought was the center and then divert north.

Surprisingly, they encountered little turbulence. On their right was a feeder band to Marge that offered another bank of severe weather. As advised, they inched over toward the left wall. They had anticipated rain, and now, they were in it. Their new and improved Voyager handled it well, without a leak in the cabin, and without losing any lift.

Voyager made its way through a wall of weather off to one side and towering clouds, then picked up a tail wind sometimes as high as 30 knots. Marge whipped them around and shot them between Saipan and Guam.

As the sun went down, they were getting close enough to clearly pick up Guam approach control on the VHF radio. They checked the Omega navigation system at Saipan. Snellman had expected smooth sailing after Saipan, but he now advised that a bumpy wake lay ahead.

They flew over Tinian and toward the Philippines. Their planned course would take them almost directly over Cebu. Rutan was familiar with the area. In the early 1960s, as a navigator on a C-124 Globemaster, he staged through there on the way to Vietnam.

Rutan was going into his third day in the pilot’s seat. Occasionally, he’d tilt the seat back and catnap, while Yeager watched the controls over his shoulder, from her makeshift seat at the side of the instrument panel.

Comfort was a thing of the past. Yeager’s head was sideways and braced against the roof, her cheek was wedged against the console, and her legs, tucked beneath her, constantly went to sleep. When she slept, it was fitfully.

An indication of trouble

As Yeager went over chart numbers, the graph seemed to indicate they weren’t doing as well on fuel as they had planned. Also, they twice tried to shut down the front engine, but hadn’t been able to maintain level flight running only on the rear engine. Something was wrong, but they couldn’t pinpoint the problem.

It didn’t seem to matter if they were hand-flying Voyager or flying it on autopilot; both seemed to require the same amount of concentration.

“We constantly had to watch the angle of attack,” Rutan said. “Any little change in air conditions would throw us out of whack, and we’d be flying at a very poor efficiency.”

When the airplane got out of trim, because the autopilot had no autotrim control, Rutan had to manually adjust to bring the center of gravity back to the proper location. It was important to stay inside the “lift over drag bucket.” That was where they would obtain maximum fuel efficiency.

“That meant flying within just one or two knots of the optimum L/D speed,” Rutan explained.

In turbulence, the pilot would push the power up, to hold the same L/D speed.

“The weather kept us higher, where airspeed had to be higher,” Rutan said.

The airplane’s theoretical, still-air range was 28,000 miles, and the flight was expected to cover 25,000 miles.

“Every time we had to climb or fly higher, we nibbled away at that 3,000-mile pad,” Rutan said.

The National Aeronautical Association’s presentation to Jeana Yeager singled her out as the first woman to be listed in an absolute record category.

While Rutan flew, Yeager was rarely idle. She monitored systems from beside the seat; carefully recorded speeds, positions, winds and rpms in the airplane log; and maintained the fuel log.

The Omega sounded a warning whenever they departed from the programmed route. After receiving their six-hour update, they’d write out the 10 new waypoints and then program them into the computer.

Just past the International Date Line, in the middle of the Pacific, the deck angle gauge faltered. That made it impossible to calculate the airplane’s weight.

They should’ve been running only on the back engine by then. They had unsuccessfully tried twice to shut down the front engine, and now, a few hours before they reached the Philippines, they tried again, and were again unsuccessful. The airplane wouldn’t maintain level flight at 10,000 feet. Either the plane was heavier than thought, and they had more fuel, or the damage to the winglets was causing more drag.

They kept encountering bad weather, which meant great luck with tail winds, but uncomfortable turbulence for the crew. Desperately needing sleep, Rutan lay back in the seat and closed his eyes, while Yeager reached across him to fly Voyager.

Yeager soon found that the airplane tended to turn off heading and then straighten itself out. The attitude gyroscope was the cause, and she feared autopilot failure. This could result in the airplane shaking off its wings, if they couldn’t immediately recover control. She was thankful they had brought along a spare gyroscope.

Yeager woke Rutan, and he agreed the ADI needed to be changed. The rewiring procedure required Rutan to push his seat all the way back and put his feet up behind the rudder pedals to get his legs out of the way. Yeager rolled onto her back and wiggled up under the instrument panel. In that uncomfortable position, she removed two computer plugs from the primary ADI and plugged them into the standby, which was already in the panel.

It was hard to see the standby ADI indicator, located at a bad angle near the bottom corner of the instrument panel. Since it was much more visible, Rutan soon began to use the two-inch JET Electronics emergency electric attitude indicator.

Rutan was concerned that Voyager wasn’t stable enough for Yeager to fly, but she eventually talked him into giving up his seat and lying down to rest.

On the ground, Burt Rutan worried over fuel numbers. It looked like Voyager was burning nearly 20 percent more fuel than they had estimated. That could indicate either a massive leak or engine problem. The ground crew also discussed a diversion to the north for better weather, but that would mean Voyager would have to pass over Vietnam or Cambodia. They called contacts in the State Department and were told that Voyager could fly over Cambodia or Vietnam only for a “life or death” emergency landing.

Surrounded by hostile weather and knowing she hadn’t been trained for many contingencies, Yeager apprehensively picked her way through storms that churned up from the Philippine Islands. After trying to deal with the garbled talked of local air traffic controllers, she had to wake Rutan, after only a few hours of rest.

On Dec. 18, day four, the weather was still bad, but they were finally able to shut down the front engine. Snellman had expected the weather to clear after the Philippines, but as they tracked along the ITCZ (commonly known as the “Itch”) a squall line was to their left. As planned, they were taking advantage of the trade winds, and although they were mostly skirting the ITCZ, typhoons and thunderstorms were in their path. In the pilot’s seat, Yeager again had to wake Rutan, so he could navigate through the bad weather.

Familiar voices

Jeana Yeager was the first woman to win the Collier Trophy, aviation’s most prestigious award, which has been awarded since 1911.

Rutan and Yeager relished the moments when they could talk and joke with the familiar voices back in Mojave. They were looking forward to making contact with Evans, team member Glenn Maben and photographer Mark Greenberg, who had flown to Singapore in a Piper Navaho, with plans to fly to Kota Bharu Airport for a rendezvous.

The Navaho flew up to meet them right on schedule, but the airport was socked in, so they headed for Hat Yai, Thailand. When an official confused the information on forms giving the Navaho’s crew permission to fly, they had to be content to sit in the tower and talk on the radio with Rutan and Yeager. They watched as Voyager’s silhouette appeared against the nearly-full moon, and the aircraft’s strobe flashed against the night sky.

The Indian Ocean

While in the military, Rutan had heard many terrifying stories about flying over the Indian Ocean and had known many pilots who went down there.

“It represented thousands of miles of open water, with lousy radio contact, tracking along the ITCZ. Little storms popped up when you least expected them,” he said.

It came as no surprise that they ran into rough weather just as they coasted west of the Malay Peninsula. Two and a half hours off the coast, with almost no radio contact, they found themselves back in turbulence and skirting the ITCZ much farther north than normal. Finally, they broke out of the weather into a starlit night. But their reprieve was short-lived. They soon hit a squall line, and for 20 minutes, they fought their way through it.

While they battled weather, they continued to puzzle over fuel consumption. They had developed a chart bearing a “how-goes-it” curve, which marked nautical miles per pound of fuel.

“How well our actual performance compared with the curve was the key to our success,” Rutan said. “Around Hawaii, we were way above the curve, but by the Philippines, we were just on it, which was barely acceptable.”

The pilots assumed the poor numbers were due to the loss of the winglets. What puzzled them, though, was that Voyager was flying as if it were much heavier than the numbers showed.

“The key figure was gross weight—the basic weight of the airplane plus the weight of the fuel,” Rutan said. “Our rates of climb indicated a heavier gross weight than our fuel logs showed.”

Their numbers had a 600-pound discrepancy. Yeager may have erred in the fuel log, due to turbulence while writing or fatigue, but when rechecked, the numbers in her logs appeared correct.

Voyager could be burning too much fuel. Melvill reasoned that the fuel hadn’t just disappeared, and that once Rutan got back to a familiar location, he could lean the aircraft out while pushing for home. The plane’s lightness would improve the numbers later on. The good news was that their optimum speed was below 82 knots, and they had no recurrence of the dreaded pitch porpoise.

Yeager was in the pilot’s seat as they came up on Sri Lanka around midday, and they headed straight across the island, swinging past 8,000-foot Mount Kandy. Over the western coast, the undercast cleared. As they started out again across the Indian Ocean, they once more worried about the fuel numbers. They should have been getting 3.9 nautical miles per pound of fuel, but even leaning it almost until the engine quit, they were getting only 3.6. The talk in Mojave was of the possibility that Voyager wouldn’t even make the Atlantic Ocean. It was hoped they could at least make it to Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory.

But there was good news. The crew, halfway between India and the coast of Africa, was cheered by word that they’d passed the 1962 record of 12,532 statute miles, set by a U.S Air Force B-52.

Crossing Africa

Bad weather dogged them while crossing the second half of the Indian Ocean. Coming into their fifth day, as Rutan slept in back, Yeager piloted Voyager toward the African coast. About 80 nautical miles off the coast of Somalia, they changed positions, so Rutan could battle the newest squall line.

The weather was running nearly perpendicular to their course and couldn’t be avoided. They were unable to climb to get out of the heavy downpour, but finally, they made it through to clear air.

Rutan was deep in thought about crossing Africa, when he saw a light flash on the canard. He looked behind them and thought he saw an airplane landing light. He advised Yeager that a fighter was tracking them, but after turning Voyager sharply to the left, he looked over his shoulder and realized it had been a false alarm. Because of his lack of sleep, he had misidentified Venus, the “morning star.”

Africa had long loomed as the biggest obstacle of the flight, and now, it was just ahead. At one point, they had planned to cross the southern part of the continent, to avoid the political complexities near its center. Their choice of a more northerly route meant that they faced a corridor over some of the world’s highest mountains and across the Great Rift Valley, which offered thunderstorms in abundance.

They approached Africa near Mogadishu, tracked south/southwest for about a hundred miles and then doglegged along the Somalia coast, to avoid the country’s civil war. Rutan and Yeager soon learned why Africa is called the “Dark Continent.” For hours, as they cruised in the dark, parallel to the coast, they saw no lights below.

As they traveled into the continent, Rutan made an important discovery. A fuel tank select valve switched the feed tank so that it could draw from any one of the 16 fuel tanks. Two sets of transducers—on the engines and on the transfer pumps—shared one readout indicator. Rutan and Yeager flipped a switch back and forth between the two sets. Now, as Rutan switched back to the fuel transfer transducers, he saw fuel bubbling through a clear plastic flow valve, and realized that, impossible as it seemed, fuel was flowing backward from the feed tank to the selected tank. That explained why the fuel flow transducers had never returned to zero flow—and why their numbers were off.

“We knew we had fuel,” Rutan said. “But we also knew there was absolutely no way to figure out how much. It looked as if there were maybe two gallons an hour flowing back through, but there was no way to reconstruct the total figures.”

As they crossed the coast near Mogadishu and headed toward Nairobi, they noted vegetation, roads and small villages below. They were headed toward a rendezvous with a chase plane, supplied by Sunbird Aviation and carrying Doug Shane of Scaled Composites, as well as other passengers.

Voyager was later than expected. The chase plane waited on the ground an extra five hours, taking time to refuel before returning to the air. At about 10:30 a.m., as the Voyager pilots neared the end of their fifth day, they spotted the chase plane near Wajir.

Temporarily piloting, Shane pulled abeam under Voyager’s left window, to make an inspection, and announced that everything looked fine. Climb tests that followed indicated an estimated 5,257-pound gross weight, placing them in the middle of the fuel curve on their “how-goes-it” chart.

Both planes headed toward Lake Victoria. At 15,000 feet, Rutan and Yeager hooked up the Demand Oxygen Controller unit and activated the pressure chamber. Yeager had been fighting a cold, and they were both weary, so neither absorbed the oxygen efficiently.

After a short struggle, Rutan was able to restart the front engine, and they climbed toward 17,000-foot Mount Kenya. Over Lake Victoria, at 20,000 feet, Rutan and Yeager radioed goodbyes to the chase plane, held at 18,000 feet.

Yeager and Rutan had hoped to cross this area earlier in the day, before the heat drove up storms. Voyager was presently in bright daylight, but as the meteorologists expected, they were heading toward ugly storms coming out of the Great Rift Valley.

They could fly to the north, over Somalia, Uganda and Chad—but they had been warned not to fly over those areas, because of the risk of being shot down. Snellman now advised the pilots not to divert, but instead to use radar to work through the storms. However, the Voyager pilots decided to fly over the danger zone, instead of toward the weather.

Knowing they would be high enough to be hidden from the naked eye, they now headed toward Uganda, which was recovering from a recent civil war. They neared the mountains, weaving their way through huge clouds, some up to 50,000 feet.

For now, with a clear lake below them, Rutan shut down the front engine to save fuel and made a long descent. Seeing the weather closing in ahead, he began to wonder if he’d made a bad decision. Three-quarters of the way across the lake, Rutan, who had begun feeling lightheaded, berated himself for waiting too long to restart the cold front engine. Would they be able to climb fast enough to get through?

He primed and cranked the front engine, and listened as it started and stopped twice, before finally running. Outside, the temperature was only 20 degrees Fahrenheit, but he didn’t have time to let the engine warm up.

He also couldn’t worry about range. With wingtips scraping the clouds, he pushed the engines for power. Rutan would soon have another worry. His partner had been trying to help dodge the storms, but now lay on the floor, unresponsive.

Yeager’s skin felt cool, she didn’t appear to be breathing and her oxygen light wasn’t blinking. He rubbed her back and neck, and after thinking briefly that she was dead, shook her to life. She awoke, complaining of a headache, before sinking back into unconsciousness.

Rutan realized that the oxygen indicator bulb on her unit had burned out. To see if she was really getting oxygen, he would have to turn around and watch the pressure gauge in back to see her pulse.

Knowing he couldn’t descend from their height of 20,000 feet, Rutan, feeling lousy himself, continued to try to shake his partner awake. Finally, he was rewarded by an angry outburst, before she passed out again into a hypoxia-induced sleep. He turned her oxygen valve up, and between dodging storms, continued to shake his partner awake.

After several hours crossing the north side of Lake Victoria, they finally started toward the plains. With the high mountains behind them, they could descend. Rutan shut off the front engine when they had reached about 14,000 feet and were heading straight west, toward the sea.

Yeager was a little more alert, but she was suffering from a bad headache and was sick to her stomach. It was now incredibly dark, and they still had 12 hours of Africa ahead.

Yeager soon had to put her own physical problems aside. Rutan had started talking about the bulging instrument panel and swelling dials and screens. The hypoxia and fatigue were also affecting him; Yeager talked him out of the pilot’s seat and into the rest area.

With her head pounding, and an airsickness bag beside her, Yeager settled in to fly. Before falling asleep, Rutan had told her to wake him before Yankee Delta, the Yaoundé navigation point. He hadn’t told her the reason, however, and Yeager let him sleep.

When Rutan woke up, the pilots exchanged places. As he read and plotted the coordinates, he was startled to learn they were three-quarters of the way past Yaoundé to the coast. That meant that two mountains near the coast, including 14,000-foot Mount Cameroon, were directly ahead. On the radar, he saw two big shadows, and angrily made a left turn of 20 degrees, to navigate around Cameroon.

As they headed out over the coast, leaving Douala behind them, he also gave a wide berth to Santa Isabel, a mountain on an island about 15 miles away. He was angry with his partner for not following instructions, but as they headed into the Atlantic, that emotion turned to relief. Yeager noted that “the macho fighter jock, who resists all emotion,” was crying.

“I didn’t know why I was crying,” Rutan said. “Maybe it was just missing those mountains, but the realization we’d made it across Africa crept over me and sent a tingling down my spine.”

Not out of the woods yet

Yeager was piloting Voyager again when the oil pressure light went on, 165 miles off the African coast. She went through steps to cool the oil and bring the pressure down, and Rutan poured a quart and a half of oil into the tank and opened the cooling ramps to get more air flowing through the engines.

As the oil pressure slowly dropped and the engine temperature rose, they worried that the engine could burn out. At 12,000 feet, they still had about 3,000 or 4,000 feet to descend before they could try to start the front engine, which had been cold and sluggish during the last few starts. Finally, a half hour later, they were relieved to see that the oil pressure was up, and the engine temperature was going down.

The Voyager pilots had benefited from moonlight for most of their nighttime flying, and they used a starlight scope when they lacked moonlight. Now, north of the Brazilian coast, heading west/southwest shortly after sunset, they flew through pitch-black sky. They knew they would have no light at all for two to three hours.

Radar warned them of a bunched handful of weather cells ahead, and suddenly, Voyager was in the middle of them. Rutan radioed Mojave for help. For the next half hour, Rich Wagoner guided them and kept them on course, threading their way through the storm.

Clouds gripped Voyager’s wingtip, tossing the aircraft around. Rutan struggled to control the craft until, suddenly, the storm spat the aircraft out.

They had banked 90 degrees—70 degrees more than ever before—and they needed to recover. Rutan knew that in this aircraft, he couldn’t just roll out of a bank that steep. He’d have to go to zero G and unload the wings. He pushed the stick forward, and, in the beginning of a dive, began to apply the right rudder. He slowly fed right aileron, and as Voyager headed down, he tried to get the wings level.

They began leveling out. At 40 degrees of bank, the nose fell, and they were in the steepest dive they’d ever made. At 15 degrees, Rutan eased back on the stick and began to pull out. They were up to half a G at 10 degrees, and he eased back more, toward normal gravity. Gradually, as the nose came back up, he pushed up the power to regain altitude.

They had made it through a terrifying ride, but the radar screen was still full of thunderstorms. With Wagoner’s continued guidance, they threaded through the first of the weather lines they could see on the radar and were relieved when they were in smooth air at 12,000 feet. After getting through the worst weather they had experienced so far, they enjoyed a few calm hours.

New fears

When the Voyager crew began to feel a vibration in the engine, Evans reminded them that the rear engine had been running for nearly 140 hours and had been running lean. He assumed that the mixture was so fuel-thin that it was making the engine run rough.

Rutan and Yeager were concerned that the vibration might harm the cooling system’s joints and connections. They had learned to avoid rpms known to set off echoing, harmonic vibrations in other systems and the airframe.

When Burt Rutan heard that the vibration occurred at about 2,000 to 2,150 rpms, he advised his brother to try to get it down to about 1,900. The engine continued running rough as they came over Brazil. It started fouling again just before sunrise, and when the oil temperature ran up, they pulled back to 1,800 rpms.

They were running very lean and were expecting head winds for the last part of the flight.

Midday offered bright sunlight and good weather, a welcome change for the fatigued crew. Later in the day, Rutan appealed to his copilot for help. He had suddenly realized that he couldn’t remember how to handle any of his chores—and he didn’t care.

Once again, Yeager coaxed Rutan out of the pilot’s seat, knowing he desperately needed sleep. When he awoke three hours later, his mental haze had cleared.

They were nearing home, and they couldn’t seem to get there fast enough. Finally, they were over Trinidad. As they came across the Caribbean and Central America and turned back toward California, they encountered head winds for the first time. That slowed them down.

Bad weather was anticipated off Panama’s coast. At the beginning of their eighth day, Rutan and Yeager approached Costa Rica instead, and marveled at one of the most beautiful sunsets of the flight. They also enjoyed incredibly smooth air.

But the moment was marred by the sudden coughing of the engine. Their projected best efficiency level was 1,800 rpms, but they couldn’t run there without the engine violently shaking, so they kept rpms at about 2,200. Twice, the engine sounded like it would quit, but to the crew’s relief, it kept going.

As Rutan slept, Yeager came up on the Costa Rican coast. They ran into offshore weather, and Rutan returned to the pilot’s seat.

Voyager ran through clouds about 80 miles from the coast. The radar wasn’t as good for landscape, but Rutan utilized his years of military experience with cruder radar to interpret the images. Close to the shoreline, the radar began painting the coast, and they could discern some details, the curve of the coast and the cumulus buildup over the land. For the first time on the trip, they turned on their radar transponder.

Two ranges of high mountains divide Costa Rica. Rutan stuck to the San Jose River valley, in the middle of the country. Coming up the valley, they saw Lake Nicaragua over the border to the north and San Jose’s lights to their left. They concentrated on staying 50 to 60 miles west of the coast, as they headed north past Nicaragua.

Just 28 gallons

They had been traveling at around 80 knots, but when they began to get head winds, they slowed to about 67 knots ground speed.

It was Julian day 357, and Rutan had returned to the pilot’s seat. In the middle of the night, and with more than 1,200 miles left to fly, they continued to buck the strong head winds—now 30 knots. They were almost due south of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, at the tip of the Baja Peninsula. Their ground speed was slowing, but they were running a lot higher than they should’ve been. Again, they considered that they might not have enough fuel.

“The nose was lower, and it was not our most efficient speed,” Rutan said. “We had to be more and more careful, as the airplane lightened, to stay in the L/D bucket.”

According to the command post, they could successfully finish the trip if they had 28 gallons in the feed tank. Rutan and Yeager began gleaning all the remaining fuel from the tanks. The forward fuselage tank on the left yielded a mere two-tenths of a gallon, and the forward boom tank offered a gallon, but they’d emptied the left main tank long ago. They found a small amount of fuel in the aft boom, and the left tip tank was nearly empty. They had thought they had a leaking cap, and it now looked like they had been losing fuel out of that tank since the beginning of the flight, resulting in a loss of 123 of its initial 170 pounds.

When they began to glean fuel from the tanks on the right side, the electrical transfer pump failed. Burt Rutan, Evans and Melvill pressured Dick Rutan to swap it out, which would require turning on the front engine. Voyager’s pilot didn’t think that was necessary. He had built the fuel system, and had designed it so the engine pump could draw directly from the feed tank.

“I have a backup system, and it’s working,” he said. “Why change procedures now?”

For several hours, they ran the engine on its own mechanical pump, direct from the right side tanks. They ran two tanks dry. When they saw bubbles come through the clear fuel line, Rutan switched quickly back to the feed tank. Although the engine hesitated, it continued to run. When he switched to another tank, he knew it was empty if the engine quit. As soon as he switched to a tank with fuel, the engine started again.

Rutan was distracted while drawing from the right canard tank and didn’t notice the telltale bubbles; air got all the way back to the engine. When the engine coughed, he switched to the feed tank, but it was too late. The amount of air in the line prevented the pump from re-priming.

Hoping the engine would start, Rutan pushed the nose down, but the fuel was lower than the pump, and couldn’t draw without the engine’s power. The plane headed down from 8,000 feet, as the rear prop windmilled, causing drag.

The left side tanks were nearly empty, and the airplane, typically right-wing heavy, now pulled off-course to the right, turning almost 120 degrees. They were spiraling down, and, now at 5,000 feet, they desperately needed to get the engine running.

As they ran out of altitude, Melvill calmly asked Rutan to try starting the front engine. Rutan knew that if they got Voyager’s nose up, so that the fuel could run back, they might be able to get the back engine going. He also knew that the maneuver might stall out the windmilling, and they might not be able to get the back engine restarted at all. The windmilling was their only starter, and they couldn’t lose it.

After switching the avionics to backup battery pack, Rutan shut off the autopilot, opened the front cowl ramps and began to nose the airplane over. At 100 knots, the front engine began popping, quit and then came to life, catching at 3,500 feet. Rutan pushed the power forward, the oil pressure came up, the prop unfeathered, and they started to level out. Fuel had flowed back down to the rear engine, and it was running.

They made the decision to leave both engines running, but leaned the front engine way down. Now that they were running both engines, they didn’t have to leave room for a restart, so they could stay down lower, where they were able to find a reduced head wind.

Running two engines threw off earlier estimates. They had thought they needed 28 gallons in the feed tank to make it home on one engine, and had determined a target of 3.9 gallons per hour. After gleaning fuel from the left side, they had still been 18 gallons short. With two running, they would need to lean all they could.

The pilots would have to go through the difficult process of replumbing the pumps. They completed the job just after 3:00 a.m. After turning the valve to the correct setting, fuel began flowing. The good pump could now collect fuel from the tanks on the right side.

When Rutan opened the solenoid that controlled the right tip tank, he found that it was full and began drawing that fuel. When the level in the feed tank rose to 28 gallons, he switched off all the valves. They knew they would make it home.

So close

The welcome committee of Burt Rutan and the Melvills, again in the Duchess, had taken flight. To rendezvous with them, Voyager would track on the Seal Beach VOR station, south of Los Angeles.

Although layers of stratus clouds were ahead of the Voyager pilots, they had heard forecasts of excellent arrival conditions. Earlier, Rutan spotted the lights of Ensenada, Mexico, and, with the use of the starlight scope, saw the lights of airplanes going in and out of San Diego’s Lindbergh Field and Miramar Naval Air Station. Now, they could see Los Angeles below them and saw that traffic was backed up going into Edwards. They came across Chavez Ravine, then flew over Mount Wilson and into the Antelope Valley, across the mountains.

When they called Edwards’ tower for traffic information, they were told the base had been shut down for the occasion. At 7:32 a.m., Dec. 23, 1986, Voyager appeared above Edwards AFB. The pilots came in over the edge of the restricted area and spotted the dry lake by the compass rose, where they would be landing. They came over at about 400 feet, made one pass and then, after the chase ships rejoined them, made several more.

When Voyager landed at 8:05 a.m., the gauge on the feed tank read 8.4 gallons. They would later find out that, after flying an official distance of 24,986 miles, 18.3 gallons were left in the tanks. They had completed the first nonstop, non-refueled flight around the world, in 9 days, 3 minutes and 44 seconds, at an official speed of 116 miles per hour.

Rutan recalled feeling very good at that point.

“I just couldn’t believe that we had made it, because I really never thought I was going to survive the flight,” Rutan said. “I honestly thought we would probably lose the airplane and our lives. Actually making it was incredible.”

He said the welcoming committee was far more than he ever expected.

“Thousands and thousand of people were there on the lakeside—just like for a space shuttle recovery,” he recalled. “It was hard to believe that all those people were that interested in our little homebuilt airplane.”

Aftermath

After Rutan and Yeager landed, the National Aeronautical Association presented the crew with a plaque recognizing the flight as a U.S. record. In all, they established eight absolute and world class records on that flight.

On December 29, President Ronald Reagan awarded the Presidential Citizen’s Medal to Dick Rutan, Jeana Yeager and Burt Rutan. In May 1987, the pilots, the designer and crew chief Bruce Evans received the Collier Trophy.

On Jan. 6, 1987, Voyager made one last flight, its 69th in all. Yeager and Rutan flew it home to Mojave, spending a couple of hours in the air while Clay Lacy shot some footage.

That summer, Voyager was dismantled and trucked on a specially modified trailer across the country to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum’s Garber Facility in Suitland, Md. En route, the airplane made one last stop in Oshkosh, Wis., where it was displayed at EAA AirVenture. Voyager now hangs in the south lobby of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

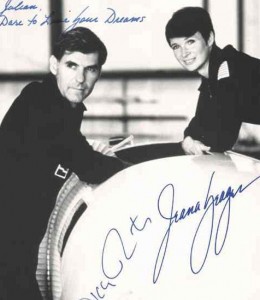

Voyager’s pilots went on the road to pay off debts that added up to more than $300,000. They had obligated themselves to appearances on behalf of their sponsors, and dozens of groups wanted to hear their firsthand accounts of the flight and its program. Although they had accomplished the “last first in aviation” together, eventually, Yeager and Rutan’s relationship disintegrated.

Jeana Yeager

The National Aeronautical Association’s presentation to Jeana Yeager singled her out as the first woman to be listed in an absolute record category. Although awarded since 1911, she was also the first woman to win the Collier Trophy, aviation’s most prestigious award.

In April 1992, she received the coveted Crystal Eagle Award, presented annually by the Aero Association of Northern California. Previous recipients included Gen. James Doolittle, Chuck Yeager and Bill Lear. For the flight, she also received the FAI’s De la Vaulx Medal.

“It was exciting, watching it all come together, exploring yourself and finding out, ‘I can do this; I’m capable,'” she later said. “It was a fun discovery period.”

Dick Rutan

The massive publicity the Voyager flight had generated allowed Dick Rutan to hit the lecture circuit, spreading his message of hard work and achievement to others, as well as his philosophy—”If you can dream it, you can do it.” The Dick Rutan Scholarship fund has gifted many thousands of dollars to young scholars.

Despite a hectic speaking schedule, Rutan is still highly active in the world of aviation. He’s held more than a dozen NAA/FAI aircraft world speed and distance records and received multiple honorary degrees. His aviation awards include the History of Flight Award, the Gold Medal Royal Aero Club of the United Kingdom, the Paris Aero Club’s Grande Medallion and Medalle de Ville Paris and the National Aviation Hall of Fame’s Milton Caniff Spirit of Flight Award.

From April 4 to June 24, 1997, he and flight lead Mike Melvill took part in The Spirit of EAA Friendship World Tour. This “Around The World In 80 Nights” flight was completed in two small experimental Long-EZ aircraft that Rutan and Melvill built.

Rutan obtain his balloon pilot’s license in 1995. In 1998, in the Global Hilton, he attempted the first balloon flight around the world.

“A number of different participants were racing to fly around the world in a balloon,” he said. “I got Pepsi Cola and Barron Hilton to sponsor it. Unfortunately, we didn’t even get out of the county.”

That attempt began in Albuquerque and ended three hours after takeoff, when the balloon’s helium cell ruptured while the team floated at 30,000 feet. The crew dramatically bailed from the crippled craft at 6,000 feet, in eastern New Mexico. The capsule landed unmanned in Texas and burst into flames. Rutan built a second capsule called World Quest, but the project ended when a rival team captured the balloon milestone in March 1999.

A strong believer that “adventure is the essence of life,” Rutan was a last-minute addition to a sightseeing airplane trek to the North Pole, in May 2000. The biplane, a Russian AN-2 Antonov, landed beautifully on unseasonably thin ice, but within seconds, the ice began to stress and crack under the plane’s weight. After a quick power-up to locate a thicker spot on the ice, the aircraft dipped nose first through the ice, sinking toward the freezing ocean. The wings of the AN-2 suspended the aircraft and gave the crew time to retrieve survival equipment. The crew was stranded at the top of the world for more than a dozen hours, until rescued by a Twin Otter from First Air.

In 2001, Rutan began working with XCOR Aerospace, test piloting the EZ-Rocket, a re-useable, rocket-powered aircraft.

Rutan’s accomplishments earned him enshrinement in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 2002.

This article is based on a personal interview with Dick Rutan, as well as information from “Flight of Voyager,” an audiodramatization of the flight, and “Voyager,” written by Rutan and Jeana Yeager, with Phil Patton. For more information on the flight, or to order the audiodramatization, hardcover book or Voyager memorabilia, visit [http://www.dickrutan.com]. Some of Rutan’s Vietnam experiences are chronicled in “Misty,” a compilation of first-person stories.

Voyager: A Crazy Dream? – Part I

- Piloting Voyager and later accomplishments earned Dick Rutan enshrinement in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 2002.

- Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager completed the first nonstop, non-refueled flight around the world in 9 days, 3 minutes and 44 seconds.

- Dick Rutan poses with a model of Voyager.

- L to R: Dick Rutan, Voyager’s well known pilot, attended the EAA AirVenture premiere of “Flyboys” last year with another popular aviator, Bob Hoover, and his father, George Rutan.