Capt. Jepp and the Little Black Book: How Barnstormer & Aviation Pioneer Elrey B. Jeppesen Made the Skies Safer for Everyone” recounts the life of one of aviation’s least known pioneers.

By Cary Baird

A new book, “Capt. Jepp and the Little Black Book: How Barnstormer & Aviation Pioneer Elrey B. Jeppesen Made the Skies Safer for Everyone,” recounts the life of the “father of aerial navigation,” one of aviation’s least known pioneers. The book delights the reader with thrilling stories of aviation’s rodeo days—a time when visionaries dared to change the world forever.

Jeppesen’s pioneering work in aeronautical mapping spawned a business that today employs 1,400 people in Denver and nearly 3,000 people worldwide. A vast majority of modern airline pilots around the world carry Jeppesen charts in their flight cases, and many private and business aviation pilots use Jeppesen charts. Nearly all airplanes that use a database to run a navigation system are using some form of Jeppesen NavData. The global company, owned by Boeing since 2000, has expanded its core competency of navigational data to serve the marine and rail industries.

Denver residents Flint Whitlock and Terry L. Barnhart coauthored the book, released in January 2007 to coincide with the 100th anniversary of Jeppesen’s birth.

“Terry and Flint have beautifully captured my father’s character, his entrepreneurial spirit and adventurous talents,” said Jim Jeppesen, Elrey Jeppesen’s eldest son. “Like most kids, when I was growing up, I didn’t realize or completely understand how truly amazing my dad’s life was. Now, as an adult, I’m still fascinated by the story. Reading this great biographical book is very rewarding.”

Young Elrey Borge Jeppesen sits atop a horse held by his father Jens, at the family farm in Odell, Ore., circa 1910. Jeppesen’s love of nature, especially birds, sparked his interest in flight.

In the book’s forward, Erik Lindbergh, Charles Lindbergh’s grandson, described the feelings and insights he gained during a flight he made across the Atlantic to retrace his grandfather’s amazing feat.

“I also gained renewed appreciation for what a marvelous tool Captain Jepp devised for pilots,” Lindbergh said. “On a small printed page—and now on a computer display screen—we have at our fingertips all the information needed to make a safe flight to and from most airports in the world.”

The idea for the book originated with Barnhart, a longtime member of Denver’s advertising scene, who also has a number of aviation connections. As a private pilot, he has used Jeppesen’s charts and maps many times. He served on the board of the Arapahoe County Public Airport Authority, which governs Centennial Airport, and is currently a board member of Wings Over the Rockies Air and Space Museum. In the mid-1990s, he was a marketing consultant for the company that bears Jeppesen’s name.

In 1927, the same year that Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic, 20-year-old Elrey Jeppesen bought his first aircraft, a 1916 war-surplus “Jenny.”

“The more I learned about Capt. Jepp’s contributions to aviation, the more determined I became about recording his story before it was lost forever,” said Barnhart. “Like many pilots of his day, he was brave, intense and determined to make his mark in the field. It turns out that his most enduring contribution wasn’t a new record, but his ‘little black book’ of navigational information.”

Whitlock, a Pulitzer Prize nominee, agreed to help Barnhart with the book when his former advertising colleague’s business responsibilities required more attention. Barnhart conducted most of the research into Jeppesen’s life, interviewing 30 people and reviewing Jeppesen’s memorabilia. Whitlock rounded out the effort by researching the early days of aviation, providing the incredible backdrop and context for Jeppesen’s life and then putting words to paper.

Decked out in Varney Air Lines coveralls in 1930, Jeppesen flew the U.S. air mail across the mountainous western states. The hazardous runs inspired him to keep a small notebook detailing the approaches and layouts of the primitive airfields of the day.

“The story of his life is an all-American tale,” says Whitlock. “He was an ambitious, visionary man, who lived in a very special time. Opportunities seemed limitless to anyone who would work hard. And he did.”

The magic of flight

Elrey B. Jeppesen was born to Danish immigrant parents in 1907—too late to be part of the first generation of inventor/pilots that included the Wright brothers and others who flew before and during World War I. Yet, he was a peer of Charles Lindbergh (born 1902) and other second-generation pilots who set new records, tested exotic new aircraft and truly dazzled the public’s imagination with aviation’s possibilities.

Jeppesen was in love with flying nearly from the first moment he saw an airplane. He took his first ride in a JN4D “Jenny,” in the summer of 1921. A barnstormer named Briggs charged him $4 for a 10-minute ride.

“We got up there, and the sun was shining, and we’d make turns and banks, and I could see the hills and the clouds and the colors brought on by the setting sun,” Jeppesen later wrote. “This was magic. I remember how great it felt when he’d go into a bank and pull it around, and you’d sit tight in the seat. The sun would shine through the canvas, and you could see the ribs, the sunlight, the river below and the mountains.”

In 1927, just after Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight, Jeppesen decided to drop out of high school and focus on a flying career. He moved from his parent’s home into a hangar at Pearson Field, near Portland, Ore. There, he performed odd jobs and eventually started a hamburger stand, serving lunch to pilots, mechanics, passengers and visitors. He began flying lessons and quickly demonstrated a proficiency and skill far beyond that of a beginner.

After only two hours and 10 minutes of instruction, Jeppesen soloed in an Alexander Eaglerock, powered by a Curtiss OX-5 engine. (Many early aviators logged time in the stately biplanes, manufactured first in Englewood, Colo., and later in Colorado Springs, Colo.)

In the early 1930s, Elrey Jeppesen became a commercial airlines pilot. He’s visible here in the cockpit of a Boeing Tri-Motor, owned by Boeing Air Transport. That company later merged with several other lines to form United Air Lines.

That same year, Jeppesen and a friend pooled their money and paid $500 for a 1916 Jenny from World War I. The friend subsequently backed out of the deal, leaving Jeppesen as sole owner. For the next several months, he gave rides in the plane to earn extra money.

He considered going back to school for his high school diploma and then trying for a college degree in engineering, so he flew down to Oregon State University in Corvallis to meet with the dean of men.

“I must have looked like a hippie,” recalled Jeppesen. “I was in my puttees, leather jacket, and the rest of . the regular flying gear we wore. I’ve reviewed it many times in my mind, trying to figure out what happened.”

The dean hardly spoke to Jeppesen, except to ask how he was going to finance his way through school. Jeppesen responded that he was going to give flying lessons, barnstorm and sell rides.

“But it was no-go,” he said, adding, “I know that if I’d been in that position and a young man came to see me and said, ‘I have an airplane,’ I’d be pretty interested in getting that kid to attend my school. But that’s not the way it goes.”

Jeppesen decided to focus 100 percent on a flying career.

The Little Black Book

Although boyish-looking, Elrey Jeppesen was flying airliners in his mid-20s and earning accolades for his safe operation and piloting skills.

Over the next several months, Jeppesen made money as a barnstormer in Oregon, California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas, finally landing in Dallas. He began a period of “job-hopping,” while he honed his flying skills. He worked briefly as a flight instructor at Love Field, and then Fairchild Aerial Surveys hired him to fly their photographers. That job led to a brief assignment, photographing and mapping parts of Mexico’s coast and interior.

Jeppesen received Mexico’s pilot license number 33. With the natives continually shooting at his plane, Jeppesen found that Mexico could be an exciting place, but the work eventually turned tedious, and he left to join Boeing Air Transport. He piloted the first plane to carry a stewardess, Miss Ellen Church. He returned to Fairchild for a short time and then moved on, first to Southwest Air Fast Express and then to Varney Air Service.

While this period may not have demonstrated job loyalty, picking his way to safe landing spots did provide Jeppesen with many experiences in navigation. He began to note landmarks, fences, poles and other obstacles along his routes. Jeppesen’s thorough and detailed nature became obvious during his quest for personal safety. Sometimes, when he landed at airports, he’d walk around the area, recording distances and heights. He recorded names and phone numbers of airport managers, as well as nearby farmers, so he could phone ahead for current weather conditions. He then purchased a 10-cent black notebook to organize his expanding notes. Eventually, other pilots learned of his “little black book” and began to ask for copies.

In 1936, Caption Elrey Jeppesen married Nadine Liscomb, one of United’s first stewardesses. She became his lifelong companion and was a vital force in the operation of his aerial-navigation chart business.

Finally, in 1934, Jeppesen decided he should charge a small fee for copies of his black book. He borrowed $450 from the bank, bought 50 binders and had 50 copies mimeographed. The little black books sold for $10 each, and pilots gladly paid the price. Some even began collecting data and forwarding it to Jeppesen. Other information sources included city and county engineers, surveyors and local residents.

Not surprisingly, Jeppesen had little time for the ladies—until he met Nadine Liscomb, a United Airlines stewardess working the Boeing 247 he was flying from Chicago to Omaha. He called for coffee, and when she entered the cockpit, both were smitten almost instantly.

“I ordered coffee, but I got Nadine,” Jeppesen often joked.

They married on Sept. 24, 1936, beginning a love affair and true partnership that would last 60 years. The young couple grew their fledgling chart business and their family, first living in Cheyenne, Wyo., and later, Salt Lake City, Utah. Jeppesen continued to fly for United, while they ran the business from their home. In 1941, he transferred to Denver, and the company moved into a storefront on East Colfax Avenue.

World War II brought additional business, with the Army and Navy both wanting “Jeppcharts.” Armed services personnel wanted Jeppesen to stay out of the military, so he could continue to run his business, providing charts critical to their military operations.

Like many civilian commercial pilots, Jeppesen did fly some missions for the Air Transport Command, a government military agency. In 1943, the ATC awarded a contract to United Airlines to fly transpacific routes, and Jeppesen was one of the pilots selected for these operations. After finished his training on the C-87, he made just one trip to Brisbane, Australia, in December 1943, before the War Department grounded him to manage his chart business.

Painful decisions

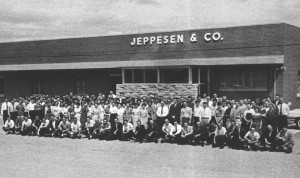

In 1961, 200 Jeppesen employees posed for a group photo. Based at Stapleton Airport, the business grew exponentially, as did the stresses and headaches of running the operation. The founder sold the company, but remained involved in its operation.

After the war ended, Jeppesen continued to fly for United. The aviation industry boomed during the postwar years, and his company benefited from the surge. In 1947, the Civil Aeronautics Administration adopted the Standard Instrument Approach Procedures, and Jeppesen worked closely with the CAA to create the template design.

Growth necessitated another move for the company, from downtown Denver to Stapleton Airport. The burgeoning aviation business, the addition of new airports and the airlines’ expansion to international markets all contributed to a nearly unmanageable pace for both the company and Jeppesen himself. Overworked and suffering from a bad back, he continued to fly a full schedule with United, while overseeing his business on his days off.

In 1954, at the age of 47, Jeppesen made the painful decision to retire from United and devote himself to his business. He had logged 18,000 hours and more than three million miles in 24 years of service. For three years after his retirement, he took a back route to his office at Stapleton, just so he wouldn’t have to pass the United sign at the company’s hangar.

His company’s rapid growth, coupled with remarkable changes in aviation and technology, almost predetermined the likelihood that management would have to change in order for the company to survive. Jeppesen hadn’t finished high school, and although he had taken some correspondence courses, he never earned a business degree. He had the vision, drive and discipline to launch the company and see it through adolescence, but it would take more to get it to the next level, and it would take deep pockets. He also worried that any inaccurate chart information could result in a fatal plane crash, potentially a huge liability. He feared that he and his wife could lose everything, including the company they loved.

In semiretirement, Elrey Jeppesen spent much time on the golf course. He’s shown in 1974, at Cherry Hills Country Club near Denver, with friend and golfing great Arnold Palmer (center) and Wayne Rosenkrans (right).

In 1961, Jeppesen sold his company to Times Mirror Corporation. The decision would benefit his company, but would lead to his eventual ouster. One provision of the sale required Jeppesen to vacate the president’s position within five years and select his own successor. Despite interviewing several highly qualified candidates, Jeppesen could find no one suitable for the job. Times Mirror finally replaced Jeppesen with Chester “Chess” Pizac, naming Jeppesen chairman of the board, emeritus. Jeppesen printed his business cards with the word “emeritus” omitted. The company’s new guard didn’t value his role and contributions, and, eventually, Times Mirror moved Jeppesen’s office out of the building and into space at the Stapleton Airport terminal.

In 1968, Times Mirror acquired Sanderson Films, a company that sold audiovisual materials for pilot training. The founder, Paul Sanderson, had been a ground school instructor who wanted to standardize a high level of quality in pilot education. Seeing the synergies between the two businesses, Times Mirror merged the two companies in 1974.

Later years

As Elrey Jeppesen’s role in the company diminished, he and his wife were finally able to take time for themselves. Golf was a favorite pastime, and they played many games with the likes of Arnold Palmer, Bob Hope, Lucille Ball and Jack Nicklaus. In 1986, deep into full retirement, they celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary at the Cherry Hills Country Club, outside Denver.

After Horst A. Bergmann took over the reins as Jeppesen’s president in 1987, he decided to find a more positive role for Jeppesen in the company—one that acknowledged and capitalized on his enormous contribution.

“I felt that if you have a historical basis for a company, it’s good to work from there and move towards the future,” Bergmann said.

Bergmann also recognized that connecting the employees with the founder could provide a solid basis for company pride and commitment. He noted that employees wanted to find ways to recognize Jeppesen and help him gain his rightful place in aviation history.

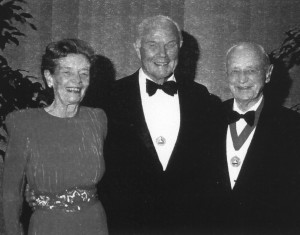

In time, Captain Jeppesen would be widely recognized for his contributions. His honors include induction into the Colorado Aviation Hall of Fame and the National Aviation Hall of Fame. He was presented the Tony Jannus Award, signifying outstanding achievement in the field of scheduled air transportation, and was a member of the Order of Daedalians. The most meaningful honor came when the main terminal at the new Denver International Airport was named for him. Many individuals and organizations, including the Silver Wings Fraternity and the Colorado Aviation Historical Society, backed the idea and worked hard to make it happen.

The City and County of Denver and Jeppesen Sanderson Inc. formed the Jeppesen Aviation Foundation to raise money for a sculpture to grace the new terminal. The commission was awarded to George Lundeen, a sculptor and resident of Loveland, Colo. Jeppesen employees contributed nearly $50,000 towards the $189,000 cost for the bronze statue. The remainder came from Times Mirror, pilots, friends and citizens.

Elrey Jeppesen and wife Nadine were all smiles when he was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1990. Former astronaut and U.S. Senator John Glenn (center) was Jeppesen’s sponsor.

Elrey and Nadine Jeppesen were honored guests at Denver International Airport’s dedication, on Feb. 29, 1995. Janet Conner, who worked closely with Jeppesen in the 1980s, spoke of that moment.

“The dedication, the naming the terminal in his honor, was the highlight of his life,” she said. “He was absolutely thrilled.”

After both Elrey and Nadine Jeppesen’s health had failed precipitously, on June 10, 1996, Nadine passed away, from complications of emphysema. Her husband mourned her passing every day. His licensed practical nurse, Annette Brott, often found him “talking to Nadine,” deep into the night. On Nov. 26, 1996, only six months after Nadine died Capt. Jeppesen “went west.” He was two months short of his 90th birthday.

Barnhart remembers meeting with Jeppesen several times, trying to get his blessing to write the book. Many had approached Jeppesen to write his story, but he never gave an official go-ahead. It was only after his death that the path cleared, and interest in a biography developed through the Jeppesen Aviation Foundation and the company Jeppesen founded.

Barnhart highly praises Conner, who transcribed his 30 taped interviews, conducted as part of his research after Jepp died.

“Janet shared my passion to tell the story, and the book wouldn’t have been possible without her help,” he said.

Originally, Barnhart envisioned a coffee table book, full of pictures but little copy. When Whitlock came on board, he saw Jeppesen’s life in the broad panorama of aviation’s heyday. After reading Whitlock’s first draft, Barnhart was sold on the expanded concept. The company was so pleased with the project that Jeppesen purchased 3,000 special leather-bound editions, for employees and customers.

Savage Press published the hardbound book, available in all major bookstores. Exclusive leather-bound editions can be purchased from Jeppesen at (800) 621-5377. Proceeds from the special edition will benefit the Jeppesen Aviation Foundation.