The Cradle of Aviation Museum building replaced two dilapidated hangars that originally housed its collection. Today, visitors can enjoy films in the modern IMAX theater.

By Henry M. Holden

Until the early 20th century, commerce relied on railroads and seaports to ship and receive goods. Natural seaports, like New York City, had well-developed docks to accommodate the freight, and these seaport towns experienced rapid growth. As railroads spread across the country, towns grew near the stops.

With the development of the airplane in the first decade of the 20th century, towns started carving “flying fields” into the land. As these fields spread across the nation, the airplane became part of the country’s cultural and economic fabric. Many of the flying fields became airports, and the airports became another link in the nation’s transportation system.

Long Island, N.Y. experienced this evolution, and with its excellent rail access from New York City, soon became a center of early aviation. Nowhere else in America has so much aviation activity been concentrated in such a small geographical area, than in the four counties that make up Long Island: Brooklyn, Queens, Nassau and Suffolk.

The World War I exhibit displays the fledgling aircraft of the time. Visitors can see that this Jenny, stripped of its fabric fuselage, was a very fragile machine.

The first airmail services began here, from these gopher-hole-covered, sometimes muddy fields. Many record-setting and historic flights took place on Long Island, including Charles Lindbergh’s famous transatlantic flight, which departed from Roosevelt Field. The first transcontinental flight was made by the Vin Fiz, which departed Sheepshead Bay, in Brooklyn, on Sept. 17, 1911. The Vin Fiz flight took 49 days, and the airplane crashed 11 times. But aviation had come to Long Island, and it had come to stay.

The activities attracted aviation companies to settle there, including Sperry, Sikorsky, Curtiss, Republic and Grumman. These companies helped make aviation an integral part of Long Island history.

Nassau County’s central area, known as the Hempstead Plains, was the scene of intense aviation activity for most of the 20th century; now its home to the Cradle of Aviation Museum. The museum, located on Charles Lindbergh Boulevard in Garden City, on Long Island, has documented the transition of aerial transportation, from hot air balloons, primitive wood and fabric flying machines, to supersonic jets and lunar landers.

This Grumman Tiger flew in early Blue Angels shows. The Grumman Aircraft Engineering Company provided jobs to thousands of Long Islanders during World War II.

The museum’s eight galleries are laid out chronologically and document 100 years of aviation and space flight. Displays include airplanes, replicas, exhibits, dioramas, photographs and films, illustrating how aviation went from a dangerous sport to a viable commercial enterprise and a safe means of transportation.

“The museum officially opened almost five years ago,” said Joshua Stoff, museum curator. “The development took 20 years. We gathered and restored the collection and planned the floor space. Before that, it unofficially existed in two dilapidated hangars, and was open irregular hours.”

A crew of more than 140 volunteers restored the museum’s collection of air and spacecraft. The volunteers worked more than 600,000 hours restoring the collection to its present state.

“We have about 50 aircraft in the museum, including a Bleriot 11, a Curtiss Jenny, a Grumman Goose and F6F Hellcat, an F-14 Tomcat, a Republic F-84 Thunderjet, an A-10 Thunderbolt II (Warthog) and a P-47 Thunderbolt,” Stoff said.

The Dream of Wings

This fragile Bleriot 11 is identical to the plane Harriet Quimby used to earn her pilot’s license. Initially, the Wright brothers didn’t want this aircraft to compete in the 1910 International Aviation Meet.

Kites, balloons and early attempts at flight in the late nineteenth century appear in the Dream of Wings gallery.

The earliest form of flight was in balloons. In 1873, Long Island was host to W.H. Donaldson, as he attempted the world’s first transatlantic crossing in a balloon. In 1896, the first recorded fixed-wing flight took place when a Lilienthal-type glider flew from the bluffs, along Nassau County’s north shore.

The Hempstead Plains

Before the sprawl dotted the landscape with tens of thousands of homes, Nassau County was a natural airfield. The only natural prairie east of the Allegheny Mountains, the Hempstead Plains provided an ideal place for transatlantic and transcontinental flights to take off and land. The Hempstead Plains gallery focuses on this unobstructed, open, grassy area.

Harriet Quimby, in her Bleriot monoplane, was a star attraction after she earned her license. In order to take flying lessons on Long Island, Quimby had to disguise herself as a man.

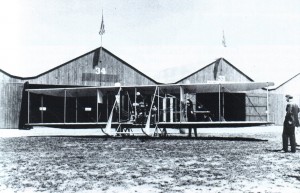

In 1909, Glenn Curtiss made the first powered flight over the Hempstead Plains, in his biplane, Golden Flyer. By 1910, three airfields were located on the plains, and flying schools and aircraft factories soon followed.

During that first decade of powered flight, Belmont Park, on Long Island, hosted one of the most important aeronautical events, in October 1910. The International Aviation Meet was only the second aviation meet in the United States. It attracted some of the greatest aviators of the day, including the Moisant brothers, Earle Ovington and Claude Grahame-White. Pilots came from as far away as Europe, to show their latest flying machines and to race, set records and win prize money.

Contentious battles took place, even at those early stages of aviation. The Wright brothers, aviation kingpins at the time, said they would sanction the International Aviation Meet, if all exhibitors recognized the Wright patents and legal position. They also insisted that only Wright aeroplanes, or those they approved, could compete. The Wrights’ proposal fell through, though, after lengthy negotiations with the Aero Club (the American representative of the Federation International Aeronautic, the world’s official record keeping and licensing organization), exhibitors and European and American pilots. The Wrights conceded and accepted a 25-percent share of the gate, which was later amended to a flat $25,000 (about $1.3 million today) to allow non-Wright aeroplanes to fly in the event.

The Red Planet Cafeteria doesn’t serve Martian food, but it does provide a casual and comfortable 2040s atmosphere.

The event inspired Harriet Quimby to become America’s first licensed woman pilot. She took flying lessons and earned her wings the next year, at the Moisant Flying School on Nassau Boulevard Airfield, in Garden City.

In September 1911, Nassau Boulevard Airfield hosted another air meet. The featured events included the first official air mail flight in the United States. Quimby flew at this meet and won the cross-country race.

The first transcontinental flight took place in 1911, when Cal Rodgers flew a Wright biplane from Long Island to California. He made the trip in 49 days, stopping 70 times for food, fuel and repairs.

During World War I, Army aviators trained at both Hazelhurst Field and Mitchel Field, now home to the museum. Naval aviators trained at Huntington, Port Washington and Bay Shore, all fields on Long Island.

In 1919, naval aviators, flying a Curtiss flying boat, made the first flight across the Atlantic Ocean. The NC-4, built in Garden City, flew from Long Island to England, stopping twice in-between.

The Golden Age

“Long Island Airports” documents a time and place that’s gone forever. Housing sprawl and businesses run the length and width of most of the island, covering an area that once boasted 82 airports.

Speed, distance, endurance and record-setting flying events became popular on Long Island. In 1923, U.S. Army Air Service Lieutenants Oakley Kelly and John Macready made the first nonstop coast-to-coast flight, flying from Roosevelt Field to Rockwell Field, near San Diego.

Charles Lindbergh made his historical flight from Roosevelt Field to Paris in 1927. This single event made aviation a household word, and people began to see real possibilities for this fledgling industry. Lindbergh’s success encouraged countless men and women to learn to fly. Lindbergh dominates the Golden Age exhibits, and a Spirit of St. Louis replica hangs overhead. A short, silent movie clip details the Lindbergh saga.

In 1929, Jimmy Doolittle made the first “blind” flight from Mitchel Field. He took off and landed a plane, using instruments only. The instruments had been developed at Mitchel Field.

By the early 1930s, Roosevelt Field was the largest and busiest civilian airfield in America, home to more than 150 aviation businesses and 450 planes. The airport closed in 1951, and is now a shopping mall.

In 1937, Pan American began the first regular commercial transatlantic airline service at Port Washington, with Glenn L. Martin Company and Boeing “Clipper” flying boats providing scheduled service from Manhasset Bay.

Twenty aircraft manufacturers established plants on Long Island. Many of them would go on to make major contributions to civil and military aviation, building hundreds of new civil, commercial and military aircraft.

World War II

The Grumman Aircraft Engineering Company and the Republic Aviation Company helped America win victory during World War II. The demands of war brought rapid growth to the aircraft industry on Long Island. By 1945, more than 100,000 people worked in the industry.

“Grumman, Curtiss and Republic were the big manufacturers here on Long Island,” said Stoff.

Grumman, founded in 1930, chiefly produced naval biplane fighters. During the war, their “cat series”—Wildcat, Bearcat and Hellcat aircraft—proved to be outstanding Navy fighters and bombers; Grumman aircraft shot down more Japanese aircraft than any other manufacturer.

Republic, founded in 1931, built more than 15,000 P-47 Thunderbolts during World War II. Long Island-based Sperry, Brewster, Ranger and Columbia also contributed to the war effort.

Postwar

Joshua Stoff, author of “Long Island Airports,” visited Coram Airport in 1985. The small dirt strip closed that year; today, it’s a housing development.

After the war, Grumman continued its tradition of producing fighters, developing the jet-powered Panther, Tiger and Intruder in the 1940s and 1950s. Grumman fighter-bombers saw widespread and successful use in both the Korean and Vietnam wars.

In the 1960s, Grumman changed its name to Grumman Aerospace Corporation, and its focus centered on building a lunar module. Grumman Aerospace played a key role in the space age, especially during the Apollo program.

Grumman’s E-2C Hawkeye is the Navy’s most advanced early warning aircraft, and is still in production. Its recently retired F-14 Tomcat is one of the best Navy fighters built. Grumman also produced the Intruder in several different versions, for bomber, refueling and electronic warfare use.

In the late 1940s, Republic also turned to jet fighter-bombers, producing the Thunderjet, and in the 1950s, the huge Thunderchief. These aircraft also saw combat in Korea and Vietnam. In the 1970s, Republic produced the A-10 Thunderbolt II, which proved to be the best tank-killing aircraft ever built.

Cal Rogers took off in the Wright EX Vin Fiz from Sheepshead Bay, in Brooklyn. Sheepshead Bay was a temporary airfield; tents housed the airplanes.

The 250 aircraft companies located on Long Island no longer build complete aircraft, but produce a wide variety of parts for virtually every American aircraft.

“For most of the 20th century, Long Island was a major aviation activity hub,” said Stoff. “We no longer have the manufacturing, but we still have some of the busiest airports in the world. We have about 250 subcontractors in the aerospace industry, here on Long Island.”

The trend with new aviation museums is to not only provide a safe haven for artifacts of our aviation history, but also to establish a family venue, with something to entertain all ages.

“Our IMAX theater was a new construction when the hangars were renovated,” Stoff said. “It can run four to five movies concurrently. Some are aviation and space related, but we have a mix of other themes.”

The museum also has a fast-food cafeteria for those who want to grab a quick bite. The Red Planet Cafeteria has a futuristic space theme, set in the year 2040.

This Queen Martin biplane was at the 1911 Nassau Boulevard Air Meet. In the event’s races, Harriet Quimby, America’s first licensed woman pilot, competed against men.

According to Stoff, the museum is hoping to expand in the near future.

“The museum currently has three hangars with exhibits,” Stoff said. “We hope to add new exhibition space and have a few more aircraft on exhibit.”

“Long Island Airports”

As curator for almost 25 years, Stoff has witness Long Island’s aviation history from unique perspectives: as a pilot, a historian and as a Long Island resident. It bothered him that airports were disappearing, and no one had documented their presence. The author of 17 aviation and space titles decided to take on the challenge, resulting in his book, “Long Island Airports.” The book was published in 2004.

“From military airfields to seaplane bases and commercial airports, Long Island has had more airports than any other place of similar geographic proportion in America,” said Stoff. “Most have vanished without a trace, but a few remain. I’ve tried to document the pictorial history of the missing and remaining airports.”

A Wright B sits on the Nassau Boulevard flight line. By 1913, the field was too small and the land too valuable, so flying activity moved to the larger Hempstead Plains field.

By the end of World War I, just 15 years after the Wrights first flew, the U.S. had about 600 official “landing fields.” Most were golf courses or country clubs. Stoff says only 13 municipal flying fields existed.

By 1927, the number of civil airports jumped to 1,036. By the mid 1930s, at the height of the post Lindbergh flying fever, that number had doubled. By the late 1930s, the first commercial transatlantic flights were departing Long Island, albeit from the bay adjoining the new municipal airport in Queens, which would soon become LaGuardia Airport.

“One can see the history of aviation just from the development of the airports here,” said Stoff. “Most of the airports started out as grass strips, with tents or wooden buildings as fragile as the airplanes they housed. Then, as technology moved forward, the planes became more airworthy, and the buildings at the airports became permanent. Long Island had at least 82 airports at one time. That’s a great many airports, considering some entire states don’t have that many. In my book, I documented 70 airports with 185 photos. Today, I estimate that only about 12 remain.”

This 1946 aerial view of LaGuardia Airport shows its two active runways and space for expansion. LaGuardia was the busiest airport in the country, handling more than 197,000 flights that year.

Stoff gathered basic information on each airport: who founded it, when did it open and when did it close? He tried to determine what materials made up the runways and what famous people visited or events took place at the airport.

“Many of these airports shut down years ago, and finding some of the photos was a real challenge. It took quite a bit of detective work,” Stoff said. “I went to old maps, newspapers and the FAA, hoping that they would have some records or photos.”

He’s the first person to try to pull all that information together for Long Island. Stoff wrote to many individuals, organizations, historical societies and museums, to track down photos.

“The most satisfying, and the most difficult part of this endeavor, was trying to gather information on the obscure airports,” said Stoff. “Roosevelt Field is well known, and so are Kennedy and LaGuardia. But with so many tiny airports to track down, I was pleased if I got something on every airport that was ever here. It was so satisfying to be able to pull it all together.”

In the early 1980s, a runway extension was built into Flushing Bay, to accommodate jet traffic at LaGuardia. The 1990s brought two new passenger terminals.

Stoff thinks he probably missed a few airports, and says any information about them will be difficult, if not impossible, to find.

“If I couldn’t find anything on these airports, then my guess is the information no longer exists, and it’s probably lost forever,” said Stoff.

“So much has happened on Long Island that some people are surprised when they hear that they’re living in a development that was once an airport. Most people who shop at Roosevelt Field Mall, for example, have no idea that it stands where Lindbergh departed for his transatlantic flight.”

Present day

In January, James Volkert came aboard to serve as interim director of the museum, following the departure of Eric Ricioppo, president.

The Arkansas resident operates James W. Volkert Exhibition Associates, is the former associate director for the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington and previously was director of exhibitions for the National Museum of American Art.

While the museum has a cadre of “propellerheads,” as Volkert calls individuals who have a hard-core interest in airplanes, the museum has failed to attract many repeat visitors, resulting in financial difficulties. Volkert is confident the museum can improve its programming, attendance and finances.

“I’m optimistic about the potential,” he said.

Financially, he said there would be an increased emphasis on securing state and federal grants.

An aerial view of John F. Kennedy in 1995 showed very little vacant land. The airport sits on the marshlands of Jamaica Bay.

“That’s something this museum hasn’t done to a great degree,” he said.

Volkert will spend four months at the museum reviewing operations and looking for a permanent replacement. He’ll observe traveling and changing exhibitions, and look into ways to use the IMAX theater and atrium to generate revenue when the museum is closed.

Volkert is also scrutinizing collaboration with other local museums.

“Rather than thinking of these as independent organizations, I’d like to see joint ticketing and other cooperation between the Cradle of Aviation and the Long Island Children’s Museum and the Francis X. Pendl Nassau County Firefighters Museum and Education Center,” he said. “Families would view Mitchel Field as a daylong destination.”

Ideally, Volkert would like to see a corridor connect the museums so visitors can move between them without going outside.

“Long Island Airports” is available on line at [http://www.arcadiapublihing.com]. For museum information, directions and IMAX listings, visit [http://www.cradleofaviation.org].