|

By Di Freeze

As a child, Kermit Weeks was a “dreamer and a designer.” “I was always technically fascinated with things,” said the 53-year-old founder of Fantasy of Flight, a popular Florida attraction. “I liked to draw things like ships and airplanes, just a conglomeration of everything. I saw the world by drawing the technical things and building things I learned about.” Weeks was born in 1953 in Salt Lake City. His father, Austin Weeks, was an oceanographer for the government; his work later took the family to Southern California and Washington D.C. Another transfer brought the family to Miami when Weeks was 13. That same year, the Royal Guardsmen greatly affected his life, through their hit, “Snoopy Vs. the Red Baron.” |

|

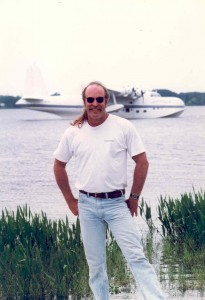

Kermit Weeks, in front of a B-24 Liberator at Fantasy of Flight, was a “dreamer and a designer” as a child. After hearing the song “Snoopy Vs. the Red Baron,” at the age of 13, his total focus was flight and aircraft.

“When I heard that song, it was a predestined cue,” he said. “My total focus became flight and aircraft.”

Today, Weeks, who admits to doing everything at a “very high level,” has the largest private collection of vintage aircraft in the world. It’s hard to keep track, but at last count, he had 140.

“Nobody has anywhere close to what I have,” he said. “The next biggest private collection I know of is about 40 planes—maybe 50.”

Fantasy of Flight allows the public to see part of his collection.

“A number of them are very rare: the P-51C, the Seversky P-35, the Martin B-26 Marauder, the Boeing 100 and the Tempest 5—you can’t get another one on the planet,” he said. “The B-24 Liberator is rare; two others are flying, but none are available. The Short Sunderland is the only four-engine passenger boat flying. We flew that across the Atlantic. It’s a boat; it can’t land on land, just water.”

Within his collection, Weeks has the largest private collection of British World War II airplanes, American fighters and bombers and privately owned World War I planes.

“I have at least a dozen original World War I planes, not including additional reproductions,” he said.

He bought each aircraft with the intention of one day flying it.

“I intend to,” he said. “I don’t know if I’ll get to all of them in my lifetime. Some of them are very big projects.”

Weeks has spent an estimated $20 million on real estate and $15 million on aircraft.

“Altogether, they’re probably worth three times that now,” he said.

Getting to know his destiny

While in his early teens, Weeks began reading voraciously about World War I aces and aircraft. Later, he started flying control-line model airplanes, which led him to start flying radio-controlled models. By the time he started high school, he had decided he wanted to be a crop duster.

“I wanted to fly low and just feel the wind in my hair,” he said. (He still enjoys the sensation, but these days, he pulls his long hair back into a ponytail.) “I used to jump off my roof with hang gliders. I’d run up and down the street with contraptions that I’d make and try to tow them behind the car.”

All that running up and down brought him to the attention of an airline pilot who lived on the street. He took Weeks to meet a friend who would further encourage the young boy’s passion.

“His friend was building a homebuilt airplane,” Weeks remembered. “I liked airplanes, and I liked building; I was always taking shop classes. I was fascinated with the concept of building your own airplane.”

By that time, Weeks was old enough to drive. He asked the man if he could continue visiting and help with his Starduster II.

Even at the age of 8, Kermit Weeks (shown with his younger brother Chris) was fascinated with aircraft.

“Fortunately, this guy was the nurturing kind,” he said. “His wife wasn’t out there helping him, and he didn’t have any kids my age, so he took me under his wing. He let me help and let me paint some things here and there.”

Weeks also spent time going through his new friend’s magazines, including Trade-a-Plane and the Experimental Aircraft Association’s publication. That led to him joining EAA in 1969. At 16, he started taking flying lessons, and after seeing a Der Jager D-1X, a modern homebuilt aircraft fashioned after a German World War I airplane, he bought a set of the plans.

“They were $40,” he said. “I mowed eight lawns for five bucks apiece. I borrowed a welder, taught myself how to weld and started building my airplane.”

Weeks built most of the aircraft before graduating from high school. He wouldn’t complete it before heading to college, but he did accomplish another goal; at the age of 17, he soloed.

“I soloed in six and a half hours,” he said. “A friend watching me on my last landing approach commented, ‘Hey, he’s slipping it in!’ My instructor exclaimed, ‘I never taught him that!’ I had read it in a book and decided to try it.”

Another passion would shape his aviation interest. During his last year of high school, Weeks competed on the gymnastic team.

“When I was learning how to fly, I was also flipping around in the gym,” he said. “I immediately gravitated towards flipping around in the sky.”

On his first official flying lesson, he learned some basic maneuvers.

“On my second official lesson, my instructor showed me how to do spins,” he said.

His incentive to get his private license was to get checked out in a Citabria, a basic aerobatic airplane.

“That was a requirement,” he said. “I had one quick flight in a Stearman. The guy went up and did two loops, and then he let me do two loops. Then, he did two snap rolls, and I did two snap rolls. That was it.”

A friend got his license first and got checked out in the airplane before Weeks did, but Weeks had been studying Duane Cole’s book, “Roll Around a Point,” and taught his friend aerobatic maneuvers.

“I showed him how to do a loop,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Make sure you pull the throttle back on the downside, and don’t let the engine overspeed. I had it all figured out. I’d done lazy eight wingovers, but I’d never done a hammerhead. I asked him, ‘What’s the speed to do a hammerhead?’ It was listed on the panel, and I said, ‘Hell, I’ll show you how to do a hammerhead.’ I pulled up vertical, kicked the rudder over, turned around and came back. And we were aerobatic pilots!”

Teaching each other how to do slow rolls was difficult in an underperforming airplane.

Kermit Weeks started taking flying lessons at 16 and soloed when he was 17. During high school, he bought a set of plans for a modern homebuilt aircraft fashioned after a German WW I fighter. He had built most of his Der Jager D-1X before graduating.

“We’d roll over, and right after we’d get upside down, the engine would quit, and it would start slowing down,” he said. “The thing would dish out the bottom every time. We couldn’t keep the nose up. So we’d go back to Duane Cole’s book: ‘If this happens, this is what you need to do.’ We used to sit upside down on the couches in our house. When you do a normal left turn from right side up, you go left aileron and left rudder. That’s how you start the turn. When you’re upside down, you have to cross control, so you go left aileron, but you have to use right rudder. In actuality it’s left rudder if you look out from the top. But you’re upside down, so it’s right. We’d practice, and we kept dishing out. We’d watch each other practice and fly. We kept teaching ourselves until we figured it out.”

When Weeks left high school, he “followed the flock” and went to the University of Florida.

“I wanted to be an aeronautical engineer,” he said. “No, let’s put it this way. I figured if I was going to have to go to school, I might as well be an aeronautical engineer. I lasted there for two quarters. I got bored. I was missing my airplane, and I wasn’t doing well at gymnastics. I just said, ‘Screw this.’ So I packed up and said, ‘Mom and Dad, I quit. I’m going to finish my airplane.'”

Although he would’ve been content to spend all his time on his plane, his parents had different plans. They gave him a choice: get a job or go back to school. He opted to attend Miami-Dade Junior College.

“I got the best of both worlds,” he said. “It allowed me to make my parents happy, continue working on my airplane and compete on the junior college gymnastic team. At the end of that year, the airplane wasn’t done. I said, ‘I’m finishing this airplane, and then I’ll get serious about school.'”

With work still left to do on the Jager, in 1973, when Weeks was 20, he began taking to the air in aerobatic flying competitions.

“We flew to the nationals and borrowed airplanes,” he said. “We flew out in a Citabria and camped out at grass fields like the barnstormers. We got eaten alive by mosquitoes. We rented a Decathlon for the contest, and I was chosen to fly second in the sportsman category. The wind sock was barely blowing, but when I dove in for my flight, the strong Texas wind at altitude blew me out of the box quickly. Completely surprised, I quit the flight after a few maneuvers. I ended up last place in the lowest category, and I’m the only person to do so and later go on to become the U.S. National Champion in the highest category: unlimited. I won the “Grogan Belt” that year, which was a prize for last place in sportsman.”

He completed his airplane at the age of 21, a year and a half after leaving the University of Florida. After finishing the Jager, Weeks was ready to tackle school again. This time, he headed off to Purdue.

“I’d been out of school for a year and a half,” he said. “I started from scratch. I took my whole freshman year—calculus, physics, all that stuff—all over again.”

The following summer, he poured his energy into aerobatics.

“I was flying the Jager,” he said. “I realized I wasn’t going to be able to compete in that airplane with any success.”

For a while, he competed in a rented Decathlon.

A change in fortune

Life for the Weeks family had always included financial ups and downs. When Austin Weeks couldn’t find work in his field, he took various odd jobs including being a Fuller brush man, selling door-to-door at one point.

“I used to help by handing out brochures,” Weeks said.

At the age of 25, Kermit Weeks entered his first World Aerobatic Championships, in Ceske Budejovice, Czechoslovakia, in 1978. Flying the Weeks Special, he was second overall, winning three silvers and a bronze.

However, a deal Kermit’s grandfather made would slowly change the family’s financial situation. Lewis Weeks had been the chief geologist for Standard Oil of New Jersey. After his retirement in 1958, he became a consultant. He directed one of his clients, Broken Hill Proprietary (now BHP Billiton) of Australia, to drill at the Bass Strait, 30 miles southeast of Melbourne. Instead of a fee, he asked for a 2.5 percent royalty. By the mid-1970s, royalties added up to $3.5 million a year.

Lewis Weeks would share his wealth with 11 heirs. When Kermit Weeks was a high school senior, he received his first royalty check, for $1,200. At college, the money continued to trickle in. That allowed Weeks to splurge and buy an aerobatic aircraft.

“I bought a Pitts Special,'” he recalled. “I could have bought a single-place Pitts, which had more performance and was less money. But I bought the two-place, because it meant so much to me to get a ride in an airplane like that; I wanted to share my passion and good fortune with people. As soon as I got the Pitts, I started giving rides.”

At the beginning of his sophomore year at Purdue, Weeks’ life took a dramatic turn.

“I had been burning the candle at both ends, flying aerobatics all summer,” he said. “I had a temperature of 103 degrees F, and they put me in the infirmary. They said I had mononucleosis and hepatitis, which were contagious. I missed the first two weeks of school. I couldn’t catch up, so I said, ‘Screw this. I’m out of here. I want to start flying aerobatics; I want to build my next airplane.’ I quit school and went home when I was 23. It was totally destined.”

Excelling in aerobatics

In the mid-1970s, Weeks worked on building the Weeks Special, an aerobatic aircraft of his own design. Before he competed it, he bought another Pitts.

“I flew my two-place up to advanced, but bought a single-place while I was building the Weeks Special, to begin competing in unlimited,” he said. “I had my sights set on a U.S. team spot.”

By 1977, Weeks had completed the Weeks Special. In it, he qualified for the U.S. Aerobatics Team, at the age of 24.

“The team selection is the year before the world contest,” he explained. “During that year, the team practices and raises money.”

In 1978, he competed in the World Aerobatics Championship in Czechoslovakia. He was second overall in the world, among 61 competitors from 18 countries. He earned three silver medals and a bronze.

“I was hooked,” he said. “I was a complete unknown. I surprised myself and all my teammates.”

On the airplane coming home, Weeks began designing his next airplane—with a bigger 300-hp engine. He built it from scratch, but the Weeks Solution wasn’t ready as soon as he wanted it to be.

“I had to fly the Special again in 1980,” he said. “I got the Solution flying before that world championship, but we didn’t get an engine oil pressure problem sorted out. I flew the Solution in 1982 in Austria. I had designed the airplane for the four-minute air show type flight, and in its first world championship debut, I won the gold medal!”

Kermit Weeks’ Short Sunderland lolls on the lake at Fantasy of Flight, after a long ordeal to get it “across the Pond” and get his seaplane ramp permitted and built.

Over the span of a dozen years, Weeks was ranked five times as one of the world’s top three aerobatic pilots and won 20 medals in the World Aerobatics Championship competitions. He won the U.S. National Aerobatics Championship twice (unlimited, 1983 and 1985) and has won several Invitational Masters Championships in different worldwide competitions.

Warbirds catch his attention

A newfound appreciation for warbirds got in the way of Weeks being able to completely concentrate on aerobatics competitions. In the period he flew, he only competed in the U.S. National Aerobatics Championship every other year, since the Reno Air Races took place the same time as the nationals.

“I would never go to the nationals in the off year, so I gave up the chance to win more national titles,” he said.

Weeks’ membership in the EAA chapter of Miami led to his interest in warbirds.

“Our chapter hosted an air race at Tamiami Airport,” he said. “Don Whittington and some of the race guys were out of Ft. Lauderdale. They decided to put this air race on. I was a supporter. I got to sit out on the pylons and watch all these World War II airplanes go screaming by. I thought, ‘Wow. This is really cool.’ I became fascinated. I thought, ‘Man, it’d be cool to have one of those things.’ I think any pilot worth his salt would love to own and fly a P-51 one day.”

Weeks took a step closer to owning a P-51 Mustang in 1979, when he bought an AT-6 from Mark Clark, for $28,000.

“I had no direct interest in it, but it was what they used to train fighter pilots in World War II, so I was intent on training the way they did,” he said. “I figured one day, maybe in a couple of years, I could afford a P-51.”

He changed his mind after an aerobatic friend bought a P-51.

“He was getting some work done on it and was going to take delivery in about four months,” Weeks remembered. “Mark called me up about six months after I got the T-6 and said, ‘This great P-51 just came on the market; are you interested?’ I wouldn’t have been, had my friend not already bought one. I’d already done everything in the T-6. I flew it cross country and had given all these rides; I flew it in an aerobatic contest. I said, ‘Send me some information.'”

By that time, Weeks was receiving more than $100,000 a year in royalty checks. The same year he bought the T-6, he splurged, handing over $155,000 for the Mustang.

“Even though my friend bought his before mine, I took delivery of my Mustang first,” he said. “The coolest day of my life was taxiing in to a ramp full of my friends in this P-51. I was 25 years old. It was my second flight in the airplane. I landed at the airport, threw my bags out of the back and started giving rides. It was awesome. It meant so much for me to get an opportunity to do that. I wanted to share it with people, and I’ve continued doing that with my good fortune.”

Weeks now has three Mustangs, a P-51A, P-51C and P-51D. One way he shares his love of the aircraft is by hosting Mustangs and Mustangs. Held at the Fantasy of Flight each year, the event gives attendees the opportunity to get up close to a variety of the popular Ford Mustangs and North American P-51 Mustangs. The most recent Mustang event was held in April.

“This year, 600 Ford Mustangs showed up and five flyable P-51 Mustangs!” he said. “We all flew for the crowds.”

Weeks Air Museum

Initially, Weeks based the few aircraft he owned at Kendall-Tamiami Executive Airport (KTMB). In 1979, he began talking about setting up a nonprofit museum, which would provide tax advantages while allowing him to share his interest.

“I grew up in a very philanthropic environment,” he said.

The YMCA in Miami is named after his mother, Marta Weeks, and several music buildings at the University of Miami are named after Austin Weeks. The geological building at the University of Wisconsin is named after Lewis Weeks, as well as several other endeavors he supported.

In 1980, Weeks began working with the Miami-Dade Aviation Department regarding the Weeks Air Museum.

Kermit Weeks’ Short Sunderland passes over the Needles, part of the Southern England Chalk Formation, on a test flight prior to flying across the Atlantic in 1993.

“It was a five-year process, including negotiations and bureaucracy, permitting and leasing the building,” he said. “We got the hangar up, but then it took us about a year to get the exhibits set up and to open the gift shop.”

During that period, Weeks continued to collect airplanes, including a P-38, P-40, Hawker Fury, Grumman Duck and de Havilland Mosquito. In 1985, he purchased the Tallmantz Museum for $1.2 million, which added another 36 aircraft. That same year, the doors of the Weeks Air Museum opened to the public. The nonprofit facility housed much of his private collection, along with other antique aircraft owned by the museum.

“When the museum finally opened, I had more airplanes than I could fit in the hangar!” he said. “And I didn’t even own the building. I realized I was in this for the long haul and needed to control my own destiny. That led me to look for property in Central Florida where the tourist industry was thriving.”

Weeks had begun to envision an aviation-themed attraction that would allow him to showcase and share his aircraft. For development of the larger, more comprehensive facility, he acquired land near Polk City, Fla., 20 minutes southwest of Walt Disney World. The location in Central Florida, right off the I-4 corridor, met Weeks’ three main requirements: enough land for a 5,000-foot runway, easy access from the tourist areas and water access for his seaplanes. His initial acquisition encompassed 250 acres.

“I sat on the land for a year or two while I focused on the newly opened Weeks Air Museum,” he said. “It took me another four years to get my runway permitted, because of some wetlands issues. We could finally see the light at the end of the tunnel to getting approval, when, on Aug. 24, 1992, Hurricane Andrew blew into my life! Life kicked me in the butt, and said, ‘You’re out of Miami, and you’re done with aerobatics.'”

Weeks had just returned from what would be his last World Aerobatic Championship, in France.

“I flew straight to the Oshkosh Fly-In to fly the show in the Weeks Solution, got home, and the next weekend, was hit by the hurricane,” he recalled. “A hangar beam fell on the cockpit and crushed the Solution in half. It hasn’t been rebuilt.”

When it struck the Miami area, Hurricane Andrew virtually destroyed the Weeks Air Museum facility and seriously damaged most of its vintage aircraft.

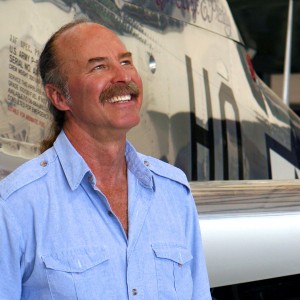

Kermit Weeks flew the Weeks Solution, his second aerobatic aircraft, in the 1982 World Aerobatic Championship in Austria, and won the gold medal.

“It was a disaster,” Weeks said. “There were 36 airplanes. We’d flown my Ford Trimotor (he had only one at that time) to a hangar in Homestead, because we knew the hurricane was coming. The wind blew the doors off the concrete hangar, blew over an 18-wheeler fuel truck inside, slid it across the hangar and slammed it up into the Trimotor. It broke both wings off and twisted the tail off. It’s currently being rebuilt. My airplanes at the museum were actually very fortunate. When the whole structure collapsed, it trapped all the airplanes inside. Had they blown out and tumbled during the storm, there would’ve been nothing left of them. Two large aircraft that were tied down outside, including a B-17, ended up blowing away. Fortunately, they never left the ground and just backed up over a mile, taking down fences along the way. They finally ended their journey at the edge of a forest after jumping a railroad track.”

Weeks looks at that time as a definite fork in the path of his life. Four months after Hurricane Andrew hit, he got the permit to build Fantasy of Flight; ground was broken two months later. Weeks focused on rebuilding in Miami, while also working towards Central Florida.

“I was coming up here, working on Fantasy of Flight,” he said. “It just killed me to go back to Miami. While I was up here, everything was fine. It was something new and creative and fun. I’d be driving back to Miami, and all of a sudden, I’d see a tree bent over and then two or three more. By the time I got back to my place, back into this energy of destruction, I was just about in tears.”

The repaired Miami museum reopened in 1994, and Fantasy of Flight opened in 1995.

“I needed a place to keep the planes, so we kept the Weeks Air Museum open,” Weeks said. “About three years ago, when our lease finally ran out, we moved most of the aircraft to Central Florida.”

Local enthusiasts took over the Miami lease and continue to operate as the Wings Over Miami Air Museum.

Fantasy of Flight

Beyond Weeks’ personal collection of about 140 aircraft, 20 more belong to the not-for-profit Weeks Air Museum. Some of the aircraft are in storage on site at Fantasy of Flight and on adjoining property.

Aerial demonstrations and “Aircraft of the Day” displays allow Fantasy of Flight visitors to become familiar with aircraft like Kermit Weeks’ P-51C, the Macon Belle.

“I have 45,000 square feet of storage space in Florida, not including the hangars where the attraction airplanes are displayed,” Weeks said. “I have five acres of aircraft storage in the California desert. Some planes are in shops around the country, and I have about six in the Sun ‘n Fun museum. I have a Hawker Tempest 5 and a Spitfire in England and A P-39 and Kingfisher in Australia.”

Weeks doesn’t only collect airplanes. He didn’t stop at his initial 250 acres in “Orlampa,” his development halfway between Tampa and Orlando, of which Fantasy of Flight is a part.

“I’m still collecting property, but it’s just raw land right now,” he said. “One day, I may be the second biggest attraction property owner in the state of Florida, next to Disney. There’s a bigger plan here. The park system is a key element.”

The tagline for Orlampa is “Where East Meets West.”

“It has local as well as global implications,” he said. “What I intend to create will become the focal point on the planet for unleashing human potential and self-discovery.”

Weeks doesn’t dream small. He’s taking the beginning steps to slowly morph what “everybody thinks is an airplane museum” into what he believes will be the next-generation attraction industry.

“We’re going to take the basic foundation of the current industry up the street, Disney and Universal, and do what Walt did 52 years ago,” he said. “He took the amusement park industry at the time—wooden roller coasters, cotton candy, bumper cars, carousels—and wrapped it around stories. He added themes and characters. Everybody said he was crazy, and they’re all out of business. There are cycles in every industry and his multibillion dollar industry is now over 50 years old. People are trying to figure out where the industry is going, because the old paradigm of ‘building a $100 million roller coaster that’s a foot taller than the guy’s down the street’ doesn’t work anymore.”

Frankly, Weeks admits his earlier ideas didn’t completely work either. When Fantasy of Flight opened, he thought people would pour in, because it was an aviation attraction. Initial attendance disappointed him. Less than a million people have visited over the past 10 years. Mainly due to operating costs and the continuation of development, Fantasy of Flight hasn’t been a financial success.

The Macon Belle, a rare P-51C, is one of three Mustangs owned by Kermit Weeks. He also has a P-51A and P-51D.

“I know everybody in the museum business, and none of them are making a dime,” he said. “I haven’t made a penny in this business. If the doors of opportunity keep slamming in your face, it might be time to go down another hallway.”

He’d like the business to be financially successful, but that’s not his biggest goal or the biggest reason he’s been disappointed in the past.

“We don’t have a product that touches everybody who comes in the door yet,” he said, adding that arousing emotions isn’t what it’s all about either. Instead, he said it’s about “making a difference on the planet.”

Weeks intends to do just that.

“In the future, when you come and experience Fantasy of Flight, you’ll see that there’s nothing like it anywhere else,” he said.

Weeks searched to discover why Fantasy of Flight wasn’t as successful as he initially imagined it would be. First, he realized not everyone is fascinated by the beauty, history and technical details of airplanes. He also increasingly realized that Fantasy of Flight isn’t really about airplanes. It’s about a path he’s been following for just as long as he’s liked airplanes.

“I started liking airplanes when I was a young kid, and when I first heard that song when I was 13, one of my passions became flight and aircraft,” he said. “At the same time, I was also fascinated by worlds around us that we don’t see: sixth sense, paranormal, metaphysical, spiritual—whatever you want to call it. That’s been as significant a path for me as flight. I may be the first guy on the planet to create something combining the physical metaphor of flight with the inner metaphor of flight, and that has become Fantasy of Flight.”

The Fantasy of Flight concept is timeless and universal.

“First, everybody’s on a journey,” he said. “Second, at each step—as a kid, a teenager, on your own, as a new parent—you see the world differently. Your perception of reality changes, and in effect, you create your own reality. In 10 or 20 years, you’re going to see truth and reality completely differently. You may not see the changes, but in effect, we really are different people from moment to moment. Six and a half billion people are running around on the planet, with different concepts of what truth and reality are, and that changes from moment to moment. Lastly, something draws us beyond ourselves—to see things differently and become different tomorrow than we are today!”

Fantasy of Flight is all about taking that step of being drawn beyond yourself. That’s where the critical difference between aircraft and flight is manifested.

“Although not everybody likes airplanes, everyone has a fascination for flight,” Weeks said. “Everybody relates to the metaphor of reaching for the sky, for the stars—basically just reaching beyond ourselves. And we all soar in our imagination; we all fly in our dreams. Why is that? I think it’s because flight resonates to the core of who we truly are. Flight is the most profound metaphor of something we all relate to. It symbolizes freedom, pushing our boundaries and reaching beyond ourselves—not only in the physical worlds, but also in the ones that lie within us as well.

“A hundred-thousand years ago, man was drawn beyond himself. Today we are, and in a million years, if we’re still here, we’ll be drawn beyond ourselves. We’re motivated and inspired to go beyond ourselves. But people limit themselves, by their beliefs and by what they think they are.”

Weeks said that’s key to understanding his business.

“I’m not in the ride business, the entertainment business or the attraction business,” he said. “I’m not in the museum business. I’m not here to teach about airplanes or history. I’ll use all those as a means to an end. If everyone’s on a journey, then Fantasy of Flight is in the travel business for that journey of life. We’re not here to tell you where to go in your travels. Fantasy of Flight is here only to bump you along your journey and encourage you to continue traveling. We’ll use the metaphor of flight and entertainment to help you self-discover your own human experience.

“Our mission statement is ‘To light that spark within.’ That spark is symbolic of who we truly are. We’ll focus not on what our differences are, but on that which we all have in common—and do it in a way everybody can relate to. We’ll create paradigm shifts, but you will decide the next step you’ll take and the direction you’ll go: What are you trying to accomplish in your life? Where are you headed? Why are you here?”

Weeks plans to expose people to all the experiences that life has to offer by designing features that are thought-provoking and emotionally engaging. Along the way, he also believes he’ll create a multibillion dollar business. One part of his plan is to create less expensive ride and attraction elements that have more take-home value than the existing industry.

History and aircraft—like this Lockheed Vega, shown with a ’32 Chevy Sedan—will be used as a means to an end. Kermit Weeks plans to use the metaphor of flight, and entertainment, to help visitors “self-discover their own human experience.”

“Instead of only surface-level entertainment and a few fun memories, I hope you’ll take home something inside you that relates to and directly impacts your experience of life, “Weeks said.

Currently, Fantasy of Flight offers plenty to admire within its period buildings. Besides several airplanes, there’s a themed art deco restaurant, exhibits and displays celebrating aviation history, including the Tuskegee Airmen story, and shop tours. It also offers Fightertown flight simulators and motion rides like the Virtual Flight Explorer.

“One of the things we’re most proud of is our immersion environments,” Weeks said. “In one experience, you’re briefed and go on a B-17 bombing mission. We want to put you into a realistic environment that you can touch, feel and smell. You’re part of it. Eventually, we’ll adapt ride technology with these immersion environments and deliver them in a way that will make you question your own journey through experiencing someone else’s.”

Museum-inclined visitors will have totally different encounters beyond the normal fare. Weeks recently created 10 audio experiences to nudge “travelers” on their way.

“This is our first pass at developing how we’ll deliver our future product,” he said. “You put on a headset and stand in front of one of my airplanes, like you would in a normal museum. But, you won’t hear the typical museum information: ‘This airplane was built in 1942,’ etc.’ Our design mission is to create thought-provoking and emotionally engaging experiences that bump you off center, and this is exactly what we’ve created. Audio offers the least expensive way to develop our concept and make improvements.”

One of the audio experiences tells the story of Douglas Bader, a Spitfire pilot who managed to become one of the Royal Air Force’s top WWII aces, despite having lost both legs in a pre-war flying accident.

“The basic format starts with a thought-provoking question,” Weeks said. “In this case it’s, ‘How many times in life do people put handicaps on you?’ Then we deliver the story of Douglas Bader. But we don’t tell you the story; you are Douglas Bader!”

Weeks’ voice breaks as he talks about this hero.

“It took me three takes to even get the narration started, because I got so emotional,” he said. “That’s how powerful these can be. People didn’t want Bader to fly; they told him he was handicapped. But he kept pushing them, and they finally just let him go. He ended up being the fifth-highest scoring ace in the RAF! He was shot down, and the Germans captured him. He was such a pain, repeatedly trying to escape, that they threatened to take his prosthetic legs away. They put him in the highest security POW camp, and he sat there for four years until the end of the war.”

Still as Douglas Bader, you return to England after the war, and you find yourself standing on a ramp full of almost 300 airplanes.

“The engines are starting,” Weeks describes. “You hobble over to an old friend, a Spitfire, and climb in. As you start the engine, you can’t help but reflect on your journey. The audio continues: ‘Your own country didn’t want you to fly; they put a handicap on you. Everyone tried to hold you back, but in the end, the tables have turned. You are now out front in a Spitfire, and you’ve been asked to lead a fly-past celebration of 300 airplanes, to celebrate the end of the war.’ At the end, you must reflect on your own life: ‘How many times have people put handicaps on you—whether it’s your family, your friends or society? Are they trying to help you, or are they trying to look out for themselves, because perhaps they don’t want you to be successful?’ You find yourself thinking, ‘I need to look at my life a little differently and question who is trying to handicap me.’ As ‘God Save the Queen’ plays, and your Spitfire is taking off, we leave you with the last hook: ‘What kind of handicaps are you putting on yours

elf? And what are you going to do about it?'”

Weeks said that after listening to each six- to eight-minute experience, guests will think about their own reality from a different perspective.

“So, you see, it’s not about airplanes or history,” he said. “It’s about using them to deliver the human experience in a way that you self-discover yours! We don’t tell anybody what they have to do. We create an environment for people to self-discover themselves and their own reality. And best of all, we do it with the most profound and least intrusive way ever created to plant seeds of change—with entertainment!”

Weeks said Fantasy of Flight is definitely getting off the beaten path of how things have been done in the past.

“We’re going to create paradigm shifts,” he said. “We’ll suck you into a story, and you’ll become immersed in it. Our new audio experiences are like old-time radio, with sounds and character voices. I’ve seen people’s eyes watering when they finish listening to some of them; they’re great! Everybody resonates with something different in their lives, because everybody is at different points on their journeys. I’ve seen people sit down on a bench, going, ‘I need to rethink my life.’ One person told me, ‘I need to bring my son back here. He’s wallowing in life right now and has got to listen to this!'”

“All of Life is a School”

Weeks plans to use another tool towards his long-term goal of helping to shift global consciousness. His children’s book, “All of Life is a School,” introduces the first round of airplane characters he’s developed for Fantasy of Flight. He expects to publish the book in June.

“This product begins to define and brand the concept of what Fantasy of Flight is all about,” he said. “The characters in the book are based on real historic airplanes that represent the period when boundaries were being pushed. All these airplanes live at this mythical airfield called Fantasy of Flight, where they’re reaching beyond themselves, trying to become more tomorrow than they are today.”

The main character in the book is an airplane named Gee Bee Zee.

“The original Gee Bee Zee is the little yellow airplane that won the Thompson Trophy in 1931,” Weeks explained. “In the book, his brother is Jimmy G. Gee Bee. They’re the Gee Bee brothers. The original aircraft don’t exist anymore, but I have reproductions that fly. I now own the Gee Bee trademark.”

Best-selling author Richard Bach and director Peter Jackson have told Weeks his book is a sure hit.

“I originally wrote it as an animation script and wrote five songs for it,” he said. “But I couldn’t afford to make the film, so I cut it down to a 64-page ‘Cat in the Hat’-size book. The illustrations are great. They were done by ex-Disney trained artists.”

Weeks envisions a line of related products to follow.

“I have treatments for another dozen Gee Bee books; the merchandising potential is huge,” he said. “In Fantasy of Flight’s gift shop, we’re going to start selling little character shirts for the kids, and other things. One of the next products will be a DVD. A kid can put the DVD in, and Mom or Dad won’t have to read the book out loud. You know how kids are. I’ve got a 3-year-old little girl, and I’ll bet I’ve seen Cinderella 150 times!”

Moving into the future

Weeks has a long way to go before all his visions become reality.

“The park is going to be way bigger than what we currently have constructed,” he said. “We just built the next building and got in it last year.”

This is the first building in what will be the park area.

“Right now, we do our maintenance and have daily tours over there,” Weeks said. “The current facility was intended only to be my shop for the restoration and maintenance of the collection. It will become a back-lot tour one day.”

Plans are moving forward for conference facilities, beginning with a side building that’s been dubbed the Orlampa Conference Center.

Weeks has decided to feature a “100-year chunk of history.”

“I needed to define the limits of my collection,” he said. “Early flight to early jets really summarizes aviation. I really have no need to collect jet airplanes after Korea or propeller airplanes after World War II. Remember, our future focus is not to teach history; it will be to use history.”

Weeks said that, eventually, every airplane displayed will be in its own period environment.

“In Paris, in 1910, they did expositions in the Grand Palais; we’ll have an early exposition hall,” he said. “The pioneer airplanes will be in an environment like the ‘magnificent men in their flying machines.’ We’ll have a World War I airfield, with opposing sides, and an airfield setting that will be the Golden Age of aviation. In another area, you’ll see the late ’30s and early ’40s, what you would have seen during World War II. Our current building is of that period. We have eight acres down on the lake, where we have a seaplane ramp. We’re going to do a 1930 recreation of a Pan Am Clipper base. The big flying boats will go down there.”

The rest of the Orlampa concept includes two other components.

“The second is to expose people to the many aspects of the human experience,” Weeks said. “This could be anything that relates to its four elements: body, heart, mind and spirit. Seeing what life has to offer will help people decide what next step in life they want to take. This whole thing will feed itself. Businesses that offer products relating to the human experience will support Fantasy of Flight, because we’ll deliver potential customers to them. Their products could be CDs, classes, books, spas, seminars or maybe retreats.”

Weeks explained the third aspect of the Orlampa concept: Having so many people serious about the human experience in one location will result in an organization that stays at the cutting edge of human potential technology and shares that information.

“This information gets dumped back into the parks, where the whole process begins again, and here goes humanity in an upward spiral!” he said. “I truly believe we’ll create something that can help make a very positive difference in the world.”

Weeks: there’s no place like home

One of Weeks’ most exciting developments lately has been the birth of his daughter. Up until recently, Katie stayed close by her mother’s side, but lately, she’s bonding more with her dad.

“In the last couple of months, she’s paid more attention to me,” he said. “We get up and go sit out in the hot tub in the morning. We took a walk on the trail the other day, and I took her to the park. She loves animals and she’s totally into the princess scene. She loves watching DVDs; she was barely 2 when she figured out how to use the remote!”

One of his friends recently wrote a piece of music for an album and named it “Katie Weeks.” That led Weeks to pen words for “Daddy’s Little Girl,” describing the love and pride he has for his blue-eyed, curly-haired daughter.

“Serendipitous things like that continually happen in my life,” he said. “It’s a great tune. These words started floating through my head, so I started writing them down. I went to a studio and did a rough vocal track and laid it over the original instrumental deal. I’m going back to the studio, where I’ll record it properly.”

Friends tell him it will be a hit. Many dads who’ve listened to it have been teary-eyed by the end of the song.

“Everybody’s told me, ‘That’s the greatest thing you could ever leave your daughter,'” he said.

Katie’s parents met through a friend.

“We were totally meant to be,” Weeks says of Teresa, whom he married in May 2000. He adds that their daughter was “never supposed to happen.”

“They told Teresa she’d never have kids,” he said. “Katie started showing up in dreams about three years before she arrived. I was sitting in my house one day, probably a year and a half before she showed up, and her energy wafted right through me. I knew everything about her: her personality, that she’d have curly hair and like music. We kept getting these messages that she was coming. We said, ‘We’ll believe it when we see it.’ She showed up and looks very much like me.”

Weeks has other musical talents beyond writing lyrics. He plays the guitar, banjo, fiddle and piano.

“I started with the guitar in the ’60s, when everybody was picking one up,” he said. “I’ve been fascinated with music, and I pretty much play by ear. Lately, I’ve been creating songs on the piano.”

Weeks sometimes treats those visiting his spectacular office and penthouse to a song on his baby grand piano.

“Before the office was finished, the piano was stored in my house,” he said. “After I walked by it for about three months, I said, ‘I can’t own something like this and not know how to play it.’ My dad always played the piano growing up, but you know, ‘the shoemaker’s kid goes barefoot.’ So, I did everything my dad didn’t. I started playing around with the piano about 10 years ago and began learning some songs. When I started working with animation, I tried writing songs.”

Weeks’ interests include snow and water skiing, as well as motorcycles, but his family has taken top priority.

“It looks like I might sell my motorcycle,” he said. “I haven’t ridden it in a couple years.”

Reflecting on his life, Weeks said he’s living a fairy tale—one in particular.

“Every day I’m surprised, as a ‘yellow brick road’ continues to unfold before me,” he said. “I know I’m creating something that has phenomenal potential—something that transcends way beyond the airplane industry.”

A sign outside his office door says, “Toto, I think this man can help us!” He explains his fascination with the fictional land of Oz and reveals which character he’s endeavoring to be.

“It’s kind of a joke, but it’s not,” he says. “By default, I’m the Mayor of Orlampa, because I own it. But I’m striving to become the Wizard of Oz, because of what he symbolizes! It’s a metaphor for what I’m really trying to do here. Like Dorothy, each and every one of us is on a journey. And like Dorothy, each and every one of us has all the tools we need at our disposal to realize our dreams and get back home. The Wizard bumbled along with a different perspective of his world and a fascination for flight. In the end, he helped others realize their dreams and get back home.”

Kermit Weeks has come a long way since 1979, when he bought his P-51D, Cripes A’Mighty, at the age of 25. He now has the largest private collection of vintage aircraft in the world.

Unlike the characters of Oz, Weeks seems to have it all: a family he adores, more aircraft than he’ll ever fly and a life he’s living to the fullest. With all that, what continues to drive him?

“I don’t have to do this,” he said. “I could easily just play and not share any of my talents and good fortune, but I know what I came here to do. I absolutely know, beyond a shadow of a doubt, I can and will create something that will have a major, positive impact on this world.”