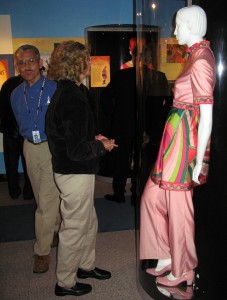

Visitors to The Museum of Flight in Seattle view its exhibit, “Style in the Aisle,” a look at the roles and fashions of flight attendants.

By Henry M. Holden

A new exhibit premiered in February at The Museum of Flight in Seattle. “Style in the Aisle,” on view in the Great Gallery through June 2, draws upon the museum’s extensive collection of airline flight attendant uniforms and artifacts, including flight bags, accessories and glamorous photographs, to help tell the story of the flight attendant.

Annie Mejia, exhibit developer, interviewed about 60 flight attendants and searched through Boeing archives for photographs. She also received research assistance from U.S. Airways, United and other airlines, which led to a deluge of people wanting to donate their uniforms.

The exhibit covers the history of flight attendants through their fashion, stories and roles in creating new standards for aircraft usefulness.

Of the more than 100 uniforms received, Mejia picked 12 uniforms and matching accessories that display styles ranging from the 1930s through the flamboyant 1960s and 1970s. The collection includes creations designed by Parisian Jean Louis, Italian Emilio Pucci and artist/designer Mario Armond Zamparelli. Trans World Airlines, Hughes Airwest and Braniff International represent a few of the airlines that flew the groovy garb featured in the exhibit.

“Shoes were missing from most of the uniforms,” said Mejia. “I had to go on eBay to buy them.”

Mejia explained that the exhibit is temporary to protect the history represented by the collection.

The progression from conservative uniforms to colorful and flamboyant fashions and back to conservative mirrors the public image of the flight attendant’s role. These PSA stewardesses are wearing the trendsetting uniforms of 1974.

“Our building is all glass, and the sunlight would quickly fade the garments,” Mejia said.

Mejia explains that the exhibit isn’t simply about fashion, although the project began that way. That changed when she began interviewing some of the women who had been “stewardesses.”

“Last September, I started my research by interviewing four women from United Airlines; three of them are retired,” she said. “Back when they were hired, they were in a profession that included only women. They were treated differently than other professional workers. It made me realize that having an exhibit just about fashion would be an insult to them; the scope of the story had to be the history of the flight attendant profession.”

The exhibit covers flight attendants through their fashion, stories and roles in creating new standards for aircraft usefulness. It also illustrates their vital involvement in the development of equitable working conditions for women in the United States.

United Airlines honored the eight original flight attendants by putting their names on a Boeing 747.

For more than 75 years, flight attendants have worked to make airplane passengers feel safe and comfortable. Often romanticized, admired and sometimes underestimated, they’ve been the public face of air travel.

In 1930, Boeing Air Transport hired eight young nurses to fly as cabin attendants to add a sense of safety to concerned passengers. The move was prompted by a letter from a Boeing Air Transport employee, who saw value in hiring young women to “serve food and look out for the passengers’ welfare.” The flight attendant soon became a fixture in both commercial aviation and popular culture. In the early days, they wore nurse-like gray uniforms in the cabin and military-style wool suits and caps outdoors. Passengers welcomed the extra service and friendliness of the cabin attendant onboard.

Alaska Airlines flight attendants wore “Golden Samovar Service” uniforms in the early 1970s. High fashion and fancy food were used to lure the passengers.

“Up to World War II, the rules said they had to be registered nurses, female and unmarried,” said Mejia. “If they got married, or were 32 to 35, considered old then, they had to retire. They had to be a certain height and weight, and that led many women to go on severe diets. Most of them lasted only two or three years, because they’d meet pilots or wealthy passengers, get married and have to give up their careers.”

The progression from conservative uniforms to colorful and flamboyant fashions and back to conservative mirrors the public image of the flight attendant’s role over the years. The airline hostesses of the late 1940s and 1950s were expected to be feminine but modest. Conservative uniforms, white gloves, hats and spectator shoes, notable for their two-tone color, gave the cabin attendants an attractive and professional look.

“The 1964 Civil Rights Act began to change that,” said Mejia. “It was slow at first, but then airlines raced to stay ahead of the competition by hiring artists and fashion designers to create distinctive images for their flight attendants. The modest suits of earlier years gave way to colorful outfits.”

Between 1972 and 1977, Hughes Airwest flight attendants wore go-go boots, hot pants, fake eyelashes and bouffant hairstyles.

Mejia said that by the early 1970s, courts decided airlines couldn’t force flight attendants to retire because of age, marital status or pregnancy. Also, airlines had to start hiring men for those positions.

In the 1970s, competition became more intense among airlines. Before jets, passengers had few choices; only one or two airlines serviced certain routes. When jets became popular, passengers had more choices, because many of the airlines began overlapping routes.

Fancier food and fashion lured passengers; flight attendants became marketing icons. Skirts got shorter, and attendants wore go-go boots, hot pants, fake eyelashes and bouffant hairstyles. When airlines flew similar aircraft on similar routes, at comparable prices, the menu and the flight attendant’s uniform became a means of differentiation.

A visitor reads about the now-rare helmet hat from the Braniff Airlines flight attendant uniform of the 1960s. Pastels were popular then, but styles would evolve into daring uniforms.

“The 1970s also saw the price of oil go up, and deregulation came along in 1978,” said Mejia. “To keep the ticket prices down, the airlines had to drop the exotic food and lavish lounges to make room for more seats for passengers.”

The airlines also dumped the flamboyant fashions.

“That’s when they decided to make the uniforms look homogenized and more businesslike,” said Mejia. “To inspire loyalty among passengers, they offered frequent flyer clubs. That’s when passengers became customers.”

Times were changing quickly in the airline industry.

“The 1990s had air rage issues,” Mejia said. “Overbooking flights and making people wait for hours in airports or on airplanes became common. Of course, since the flight attendant is the first person the passenger sees, the flight attendant becomes the target of passenger wrath.”

After 9/11, the focus of the flight attendant again became security and safety.

“The flight attendant is once again the bastion of safety, and the passengers’ welfare takes precedence,” said Mejia. “They’re no longer ‘sky waitresses’ as they were in the past.”

For more information about the exhibit, visit [http://www.museumofflight.org].

Displayed in the exhibit is a colorful Braniff Airlines uniform from the late 1960s. Designers who added to the haute couture of the day included Parisian Jean Louis, Italian Emilio Pucci and artist/designer Mario Armond Zamparelli.