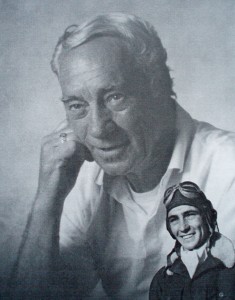

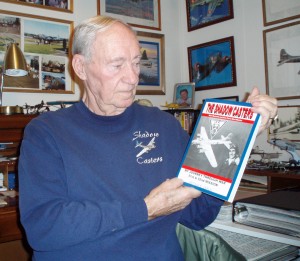

Arthur B. Unruh, who served as a B-17 tail gunner and waist gunner during World War II, published his memories in “The Shadow Casters.”

By Terry Stephens

Air Force SSgt. Art Unruh, 85, vividly recalls his 50 missions over Europe as a young B-17 gunner during World War II. Those memories are captured forever in “The Shadow Casters.” In his book, he talked about his missions and the plane he came to know so well—the B-17. He also recalled the people who served with him, including many who were lost.

He explained why he titled the book “The Shadow Casters.”

“When 1,000 B-17s fly overhead on a sunny day, they make a lot of shadows,” said the resident of Arlington, Wash.

Throughout his military service, Unruh kept diaries, took photographs and collected wartime memorabilia. The mementos, along with his military orders, now fill his office walls. The jacket of his brown U.S. Army Air Force uniform displays his staff sergeant’s stripes, World War II insignia and service ribbons, including the Silver Star, Air Medal, World War II Victory Medal and the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal.

Unruh also brought back a few of his bomber’s aerial photos of missions over a variety of European targets. With the Kodak Brownie camera he always carried, he even captured photos of his squadron’s B-17s flying in formation on a bombing mission, taken through the open waist gunner’s window. Models he’s built of B-17s, P-51s, Me-109s and many others fill his office ceiling.

He often takes models and pieces of world history from that war to Arlington area schools, where he shares his experiences at student assemblies. He also goes to classrooms, showing his photos, military decorations and insignia, uniforms and a red Nazi armband with its dreaded black Swastica. He still keeps all of the letters that students have written to him over many years.

Aerial combat

“When 1,000 B-17s fly over a country, they make a lot of shadows,” said former waist gunner Art Unruh, relating why he named his book of war experiences “The Shadow Casters.”

Unruh spent two years in uniform during WWII. His unforgettable 243 hours, 15 minutes of aerial combat spanned six months during 1944.

“I was a tail gunner for my first six missions, and then I was asked to take over the 50-caliber waist gun,” he said.

Remaining in Europe for his next 44 missions, Unruh later learned that B-17 waist gunners had the highest mortality rates.

“They shot standing up and were a clear target,” he said. “I remember one mission, when there seemed to be a pause in the fighter attacks. I started throwing thousands of American propaganda sheets out of the plane’s open waist gunner’s window while we were over our target. Just as I bent over to grab another handful, a German fighter plane attacked and one shell knocked a hole through the side of the plane. When I stood up, I saw it had come through where my head would’ve been if I’d been standing up.”

The danger on another mission came from deadly flak from antiaircraft guns near the target. As Unruh stood poised at his waist gunner’s position, the impact of a palm-size chunk of shrapnel from a nearby exploding shell suddenly knocked him off his feet. Underneath his heavily insulated flight suit that shielded him from 50-below zero temperatures was the 38-pound flak jacket that protected his life. He still has that shrapnel in his office as a reminder of his good fortune.

“I always thought that flak jacket was just too heavy to wear for the kind of active combat we were in, and I rarely wore it, but it saved my life that day,” he said.

Prior to one of his 50 bombing missions from Foggia, Italy, SSgt. Art Unruh (front row, second from left) poses with the 10 crewmen he became close to during World War II. He’s reconnected with three of the men in recent years.

He said those six months of missions with the 32nd Bombardment Squadron, 301st Bombardment Group filled his war memories with images of exploding and falling B-17s, all the more memorable because he knew many of his friends were on board those planes. Just as vivid to him today are battle scenes of Me-209s coming at his plane with blazing guns. In his last few missions in the fall of 1944, when German pilots ran out of ammunition, he saw them trying to ram their fighter planes into his B-17 and others in the formation, on orders given from a panicky German High Command.

“Many of them came as close as 50 feet,” he said. “That’s why we were able to shoot down many more planes than we usually did, although it was always hard to keep count. When they tried to ram us, I could see their faces. They looked like they were 16 or 17 years old.”

For months, Unruh had flown on B-17 missions that had targeted critical German resources and military positions, including the Ploesti oil fields in Rumania, estimated to supply 60 percent of Germany’s crude oil. Raids also bombed the Toulon submarine pens in France, Florisdorf oil refineries in Austria and an ordnance depot in Munich, Germany.

Unruh’s 50th mission, which was to be his ticket home, proved to be his toughest. On July 26, 1944, the 301st BG was targeting the critical and powerfully defended aircraft engine factory in Weiner Neudorf, Austria. According to the narrative for the Silver Star medals the Army awarded to Unruh and the rest of the crew for their heroism, the mission clearly tested their skills and resolve.

As the B-17 formations flew closer to their target at 24,000 feet, nearly 70 Nazi Me-109s and FW-190s swarmed over them in three waves of 18 fighters each, firing rockets, then 20-mm cannon and machine guns as they closed in on the bombers. In the first 15 minutes, 11 of the bombers were destroyed in the devastating attacks, while dozens more flew on toward their targets.

During the ferocious fighter attacks on that last mission, Unruh’s plane received 600 cannon and machine gun hits to its fuselage and wings. The aircraft’s radio equipment caught fire, nearly all of the oxygen system was destroyed and half of the aircraft’s rudder was blown away, including the left elevator and elevator trim tab, leaving those flight controls jammed.

Model planes and historic photos, including Art Unruh in World War II flying gear, are prominently displayed in Unruh’s office.

Prevented by fighters, flak and worsening weather from completing its primary bombing mission, the crew dropped its bomb load on an alternate target, banked the plane to the south and headed for home. With the loss of the aircraft’s rudder, it took the combined strength of the pilot and copilot to maneuver the damaged aircraft, now separated from the rest of its formation.

As the pilot headed for safety, another 20 German fighters dove at the crippled plane, guns blazing. Although five of the bomber’s seven gun stations were damaged, the crew continued to fight off the attacks until the pilots were able to lose the enemy planes in the clouds. For two tension-filled hours, the bomber strained to remain airborne for a successful flight to the 15th Air Force’s base in Foggia, Italy.

Only recently, as Unruh exchanged emails with others who had flown and fought that day with the 32nd BS, did he realize why the losses were so high on that mission. One of the B-17 pilots who survived had discovered that worsening cloud cover had made it nearly impossible for the planes to hit its target accurately, so headquarters ordered the mission canceled. Unruh’s group, however, never got that message and flew into a waiting ambush that destroyed 12 of the 28 planes.

Once on the ground, the impact of the dangers they had been through began to penetrate. “All the time you’re in the air, you’re busy shooting at enemy fighters,” Unruh said. “You don’t think about anything else much until you get back on the ground and see your butchered airplane. That’s when you fall apart. I was fortunate; I got to come back to the states and grow up. The chance of anyone making it through all 50 missions was only 27 percent. My flag goes up every day for my buddies who didn’t make it.”

Unruh said he believes that many more planes and crews would have been lost on those B-17 raids if it hadn’t been for the squadron of familiar “red tailed” P-51s and the skilled Tuskegee Airmen who flew them.

“Those planes were a welcome sight whenever they flew cover for us,” he said.

In 2007, Art Unruh served as a tour guide at Paul Allen’s Flying Heritage Collection at Arlington Municipal Airport.

In 2001, Unruh met one of the Tuskegee Airmen, William Holloman III of Kent, Wash., at the Northwest Experimental Aircraft Association Fly-In at Arlington Municipal Airport (AWO).

“Bill and I compared our mission experiences, and we realized that 57 years earlier, he and I were together 25,000 feet in the air over the Ploesti oil fields in Romania,” Unruh said.

Life back home

After the war, Unruh returned to his boyhood home in Hutchinson, Kan., where his wife, Maxine, whom he’d married in 1942, was waiting with their young son, Arthur Jr. Taking the job Carey Salt Co. had saved for him, he returned to spending his days working 600 feet underground in the mines. Later, he found work in the fresh air and sunshine with a local car dealership, handling auto parts.

Although Unruh vowed after the war that he’d never fly again, he decided in 1947 that he was ready to get his pilot’s license. He soloed at Sparks Aviation Enterprises in Hutchinson and enjoyed flying to many places in Nebraska, Iowa, Texas, Oklahoma and Missouri.

In 1952, after their second son, Jerry Wayne, was born, Unruh moved his family to Everett, Wash., where their daughter, Mary Lou, was born. He continued flying there, even buying two single-engine planes of his own over the years, each based at Arlington Airport. Until his retirement in 1984, he continued working for local auto parts dealers, leaving Piston Service Auto Parts after 23 years.

For many years, he was commander of Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 2586 in nearby Stanwood. Well known for his music, he played guitar and sang for 14 years with the Rhythm Wranglers, his country and western band that became one of the most popular in the area. After Maxine, his wife of 46 years, died in 1989, he married his present wife, Leona Mae. Today, he and Lee live only two blocks from Arlington Airport, where Unruh keeps his license active by flying with others whenever he can hitch a ride.

Sharing experiences

Unruh’s third edition of “The Shadow Casters” includes his 51st and 52nd missions, as he calls his flights in two restored B-17s that stopped at Arlington Municipal on their national tours. In 2003, Unruh’s friends surprised him with a flight on the Commemorative Air Force’s Sentimental Journey. The next year he flew aboard the Collings Foundation’s Nine-0-Nine, as it toured the Pacific Northwest.

Unruh’s love of aviation and history led him to become an active member of the Arlington Air Station group of local history enthusiasts working to preserve the few remaining buildings, including a large hangar used by the Navy when the airport was a WWII training base. There he met Jeff Thomas, a commercial airline pilot who became the first executive director of Paul Allen’s Flying Heritage Collection. The meticulously restored World War II planes, from several nations, are all in top flying condition.

“The collection was first displayed in hangars at Arlington Airport,” Unruh said. “I didn’t know what a docent was at that time, but I became one at Thomas’ suggestion. I spent the next three years, through 2007, telling visitors about the planes and their history.”

This summer, the aircraft collection will permanently relocate to Paine Field (PAE) in Everett.

“I won’t be following them, but it was a great opportunity for me to share aviation information and some of my B-17 experiences,” Unruh said.

For more information about “The Shadow Casters,” email artlee@maxxconnect.net.