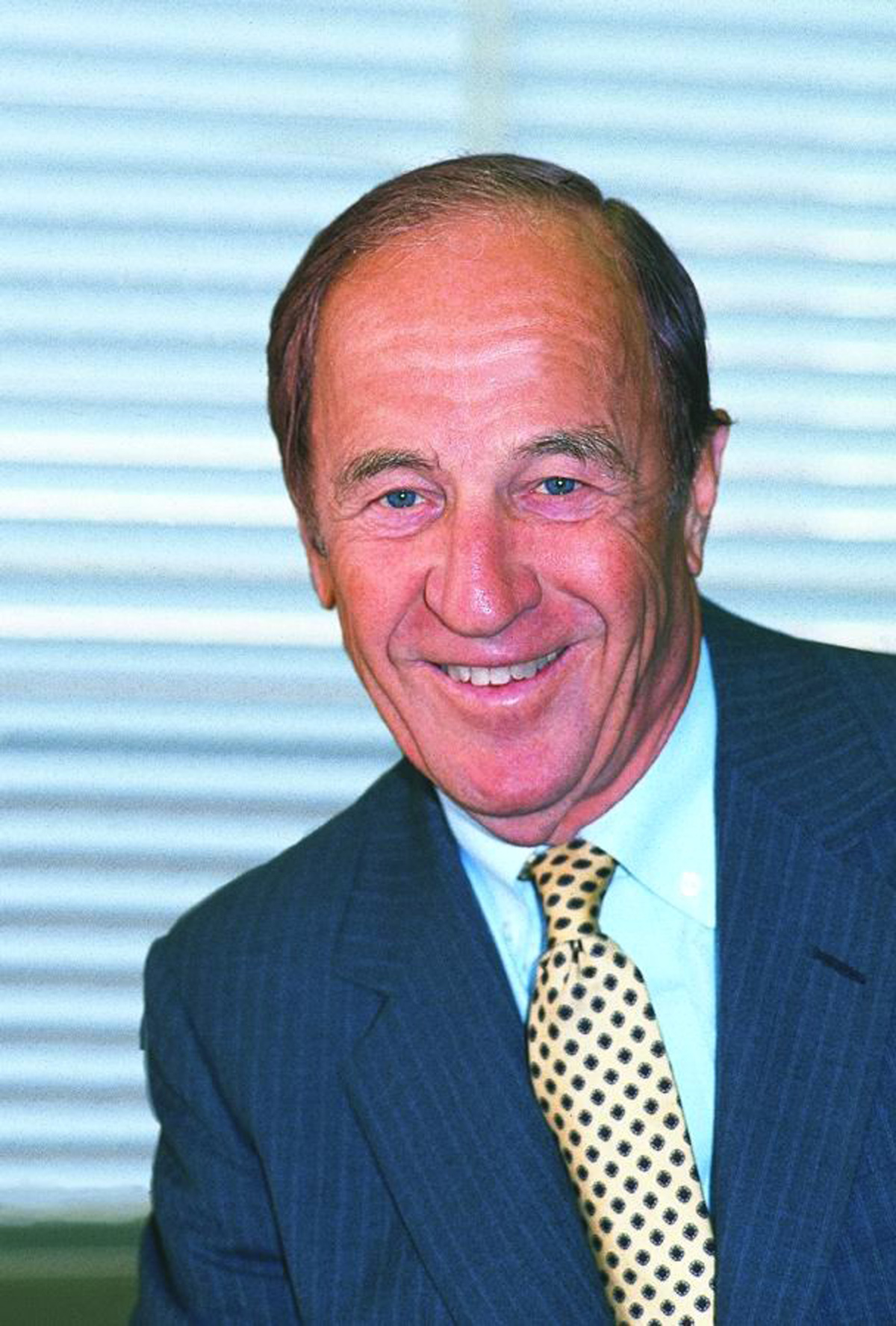

Two types of salvation are especially near and dear to the heart of A.L. Ueltschi. The first is the saving of lives. The other, equally important to him, is saving sight.

Ueltschi accomplishes the first mission through FlightSafety International, the world’s largest provider of aviation services and training, and the second through ORBIS International, an international nonprofit organization dedicated to saving sight and eliminating unnecessary blindness worldwide.

The mission of FlightSafety International is to help its customers in their quest for safe, reliable transportation.

“In doing that, we’ve helped save lives as a matter of course,” said Ueltschi, founder and chairman of the company.

Ueltschi, who has accumulated more than 35,000 hours of flight over the years, says the best safety device on any aircraft, anywhere, remains a well-trained pilot. More than 75,000 pilots, technicians and other aviation professionals train at FlightSafety facilities each year. The company designs and manufactures full flight simulators for civil and military aircraft programs and operates the world’s largest fleet of advanced full flight simulators at more than 40 training locations.

Ueltschi’s interest in flight led him to spend more time in the air than at school after he enrolled at the University of Kentucky, at his parents’ request.

“I was out flying pastures,” he said. “No airports were around. I’d tell people, ‘Come out to Black’s farm’—or somebody else’s farm—’because we’re going to put on an air show.'”

A lack of funds was one of the reasons he readily accepted when George Wedekind, president of Queen City Flying Service, offered him a job in Cincinnati, Ohio. Although it was steady work and he flew almost every day, he still dreamed of flying “bigger airplanes” for an airline. So, after logging about 2,000 hours of flying time, he applied with various carriers, including Pan American World Airways.

In 1941, while most other carriers were struggling to maintain service between a few cities around the country, Pan Am was flying scheduled service to the far corners of the world. According to Ueltschi, Pan Am’s Clippers were the “most modern, luxurious and magnificent flying machines in the sky,” and its flight crews “were the most experienced and the most respected in all of aviation.”

Ueltschi was thrilled when Pan Am hired him as a general assignment pilot. After working in the training department for a while, he crewed briefly in the airline’s “flying boats.” Pan Am assigned him to its “air ferries” before transferring him to Brownsville, Texas, the airline’s principal base for Central and South American operations. The airline later sent him to Colombia to pick up a twin-engine Lockheed 10A Electra that was to be converted to an executive aircraft. Ueltschi became the aircraft’s pilot fulltime after the modifications were completed. He would be flying for Juan Terry Trippe, Pan Am’s founder and CEO.

Initially, Ueltschi’s assignment as Trippe’s personal pilot was supposed to be for six months, but that wouldn’t be the case. His tour lasted until he retired from Pan Am 25 years later. After the Electra, Ueltschi flew different aircraft for Trippe, including a DC-3, a converted B-23 bomber and a Falcon 20.

It didn’t take long for Ueltschi to come to believe that Pan Am’s approach to flying was superior.

“Pan Am had a great training program,” he said.

For that, he credited Andy Priester, Pan Am’s head of operations, who “demanded precision.” He said that pilot training at Pan Am was rigorous, exacting and never-ending. While waiting at fixed based operations around the country, though, and when communing with other business aviation pilots, he didn’t notice the same diligence.

“A lot of airplanes became surplus when World War II ended,” he said. “Companies were using DC-3s, Lockheed Hudsons, Lodestars and aircraft like that. But the pilots coming back from the war hadn’t gone through the kind of training the airlines provided.”

When airline pilots, who were used to operating airplanes “low and slow,” transitioned to pressurized, high-performance aircraft entering the commercial fleet, Ueltschi knew it would be challenging. Pan Am assigned him to help its older pilots transition to DC-6s and Constellations.

Although the government required airline pilots to demonstrate proficiency in training at least once every six months, no similar requirement was in place for business aviation pilots. Ueltschi was correct in assuming that as aircraft advanced in technology, those pilots would also have problems transitioning.

Even if corporate pilots wanted to do transition or proficiency training, they were on their own, because no training organization was available. Ueltschi saw possibilities in giving corporate pilots a training system similar to what the airlines had.