In December 1947, Aviation Week leaked the news that a military pilot had broken the sound barrier. The Air Force didn’t confirm it until the following June. When Chuck Yeager’s achievement was finally declassified, he quickly became known as “the Fastest Man Alive.” To mark the occasion, President Truman awarded him the prestigious Collier Trophy. According to Truman, the project’s accomplishment was “the greatest since the first successful flight of the original Wright brothers’ airplane.”

While growing up in the Appalachian foothills of West Virginia, Chuck Yeager never dreamed of flying.

“I run into guys that say, ‘I hung on a fence and looked at airplanes; I really wanted to be a pilot,'” he said. “Airplanes meant nothing to me.”

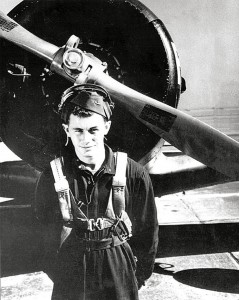

Charles Elwood “Chuck” Yeager, born on Feb. 13, 1923, spent his early years in Myra, W.Va. When Yeager was in preschool, he moved with his family to Hamlin, population 400. At Hamlin High School, he excelled at anything requiring dexterity or mathematical aptitude. Money was hard to come by, so after graduating in 1941, he never considered going to college. Instead, he enlisted for a two-year hitch with the Army Air Corps.

“I thought I might enjoy it and see some of the world,” he said.

The AAC trained him as a mechanic. Stationed at Moffett Field, California, he was crew chief on T-6s when a bulletin board notice regarding the Flying Sergeant program caught his eye.

“Cadets had needed two years of college and had to be 20 years old,” he said. “They weren’t getting enough applicants, so they opened it up for ‘aviation students.’ If you had a high school diploma and were 18, you could apply for pilot training, but instead of being an officer when you graduated, you’d be a staff sergeant.”

Although Yeager wasn’t interested in flying, it sounded inviting.

“We were busting our knuckles working on airplanes,” he explained.

Yeager took his physical on Dec. 4, 1941. Up until that point, he’d never flown.

“I took a ride at Victorville, in an AT-11 twin-engine Bombardier trainer that I was crew chief on,” he said. “I puked all over; when I landed, I said, ‘Yeager, you made a big mistake!'”

He began pilot training six months later.

“When I started flying the airplane, instead of just riding in it, I had no problem,” he said.

Yeager completed primary pilot training at Hemet, Calif., followed by basic in BT-13s at Gardner Field in Taft, Calif., and advanced training at Luke Field, Ariz. He earned his pilot’s wings with Class 43-C on March 10, 1943.

Later that month, he joined the 363rd Fighter Squadron at the Tonopah Bombing and Gunnery Range, Nevada, and began training in fighter tactics in the Bell P-39 Airacobra. When he reported to the 363rd FS, it wasn’t as a flying sergeant.

“By then, the regulations had changed,” he said. “Those of us receiving our wings as enlisted men were made noncommissioned flight officers, wearing blue bars instead of gold.”

Yeager was among 30 pilots in the 363rd that began six months of intensive combat training. In late June, he began training in bomber escort and coastal patrol operations at Santa Rosa, Calif. After a temporary assignment at Wright Field, doing accelerated service testing on a new P-39 propeller, he returned to California the day his squadron flew to Oroville, Calif., the next stop on the training schedule. The final phase of training took place in Casper, Wyo.

In late November 1943, the 357th FG sailed for England. Based at Leiston, 60 miles up the coast from London, the 357th was the first unit in the 8th Air Force to employ the P-51 Mustang.

The group logged its first combat mission on Feb. 11, 1944. Yeager scored his first aerial victory on March 4, when he downed a Messerschmitt Me-109 over Berlin.

The following morning, 18 Mustangs escorted B-24s on a bombing run. Four flights of four P-51s provided air cover during the raid on Bordeaux, France. Yeager and another pilot were to join the mission in case of aborts. When a Mustang with engine problems turned back over the Channel, Yeager pulled in as tail-end Charlie.

When he saw three Focke-Wulf 190 fighters diving at him, he radioed a warning, and his flight turned to meet the enemy head-on. Soon after, a 190’s 20-millimeter cannon hit Yeager’s aircraft. His burning P-51 began to snap and roll and headed for the ground, but Yeager was able to bail out.

Once on the ground in occupied southern France, he limped off into the woods, pausing long enough to treat shrapnel punctures in his feet and hands. A map of Europe sewn into his flight suit told him he was about 50 miles east of Bordeaux.