Reprinted with permission from Clear Creek Courant, April 21, 1999

Reprinted with permission from Clear Creek Courant (April 21, 1999)

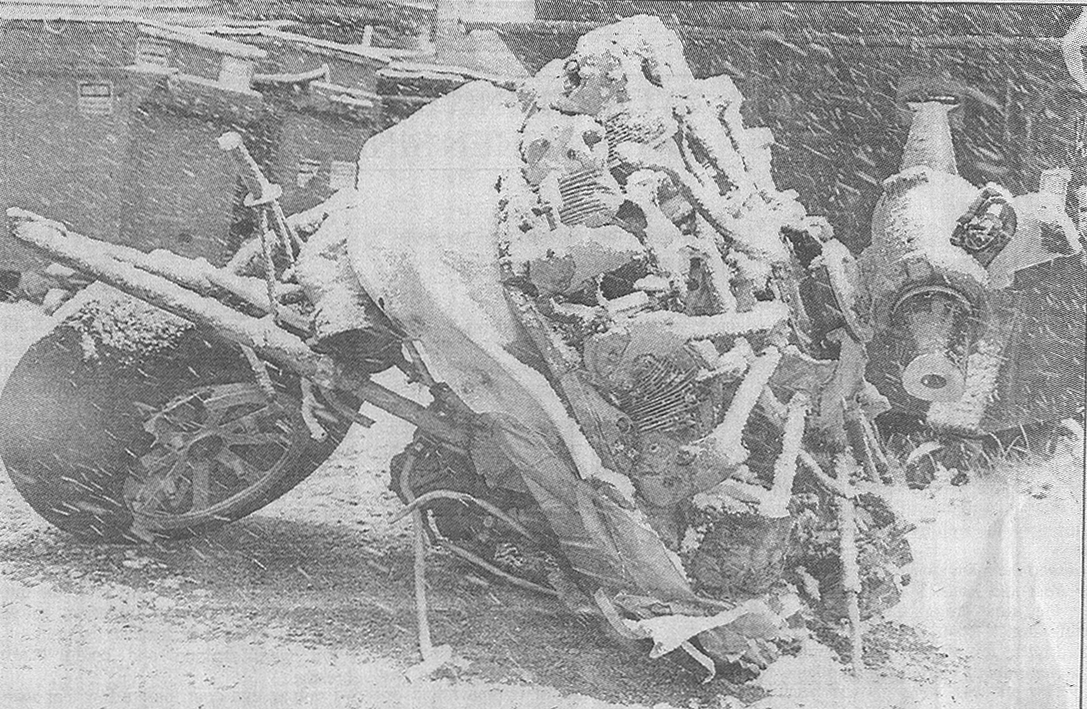

A snow storm put a fine white frosting on the few remaining pieces of a Navy plane which crashed 54 years ago in Clear Creek County, killing one and injuring another.

Before we reprint this fine article in our Airport Journals newspaper, I’d like to preface it by first saying that my Boy Scout Troop BSA 529 (Englewood, Colo.) played an interesting part in the recovery of the pieces of the small plane wreckage. As noted by Mr. Jensen, the helicopter pilot would only take several recovery loads due to the danger of the tall trees and cliffs in the area. One of my scouts, Daniel Tubbesing, made it his Eagle project to lead 16 scouts and myself, Richard Hansen (owner of Airport Journals) on a hike into this quite inaccessible area. We hauled out the final pieces in our back packs. The loads carried by each boy varied from 40 to 80 pounds. We now continue with the rest of Mr. Jensen’s article.

In September 1945, a BT-13 airplane operated by the United States Navy crashed into the Mount Evans Wilderness Area. Of the two-person crew, one man survived and one died in the accident. For 53 years the wreckage remained in the largely inaccessible forests of the Upper Bear Creek watershed. The airplane was a BT-13, a basic training airplane originally built for and purchased by the U.S. Army Air Force, but transferred to the Navy.

The BT-13, nicknamed the Valiant, was built by the Vultee Company. It became the most widely used trainer during World War II because it had a more powerful engine than its competitors. It also required the student pilot to use two-way radio communications, operating landing flaps and adjust the two-position variable pitch propeller, according to data from the UDAS Museum.

Its powerful engine and additional flight controls probably reduced the likelihood of smooth flights. In fact, student pilots nicknamed it the “Vibrator.” This valiant vibrator crashed on Sept. 16, 1945.

Forest fire provides access

The elements and treasure hunters had taken their toll on the plane’s carcass, but until last July (1998), local Forest Service Personnel had seemed willing to let it stay in the wilderness area forever.

The crash site was only accessible to hikers or to helicopters, but helicopters are banned from wilderness areas, “unless there happens to be a forest fire that needs fighting,” according to a Courant article written by Trevor McFee last summer.

One June 27, 1998, the Bear Track fire ignited in the wilderness area. Hundreds of wildland fire fighters were assisted by engine, tanker and helicopter crews.

Kris Heiny, a forestry technician with the Clear Creek Ranger District, arranged for one of those helicopters, on contract from Yellowstone National Park, to haul the debris to Idaho Springs.

Heiny said an Eagle Scout from Denver led the final salvage trip to the crash site. The scout had contacted Heiny in need of a project for his Eagle Badge. Heiny suggested he lead an expedition into the wilderness area to retrieve the smaller pieces of debris left behind by the helicopter.

The debris remained at the Forest Service Work Station at the east end of Idaho Springs until last week.

A crew from Peterson Air Force Base Air Museum (in Colorado) removed the final pieces of the airplane wreck Wednesday from Clear Creek County. Heiny had asked U.S. Sen. Ben Nighthorse-Campbell’s office for

assistance to “get it off our hands.”

The senator’s staffers put Heiny in contact with the Pentagon, and Pentagon personnel directed him to contact Peterson Air Force Base.

Representatives from the base air museum examined the debris earlier this month and Wednesday sent the three-person crew to haul it away.