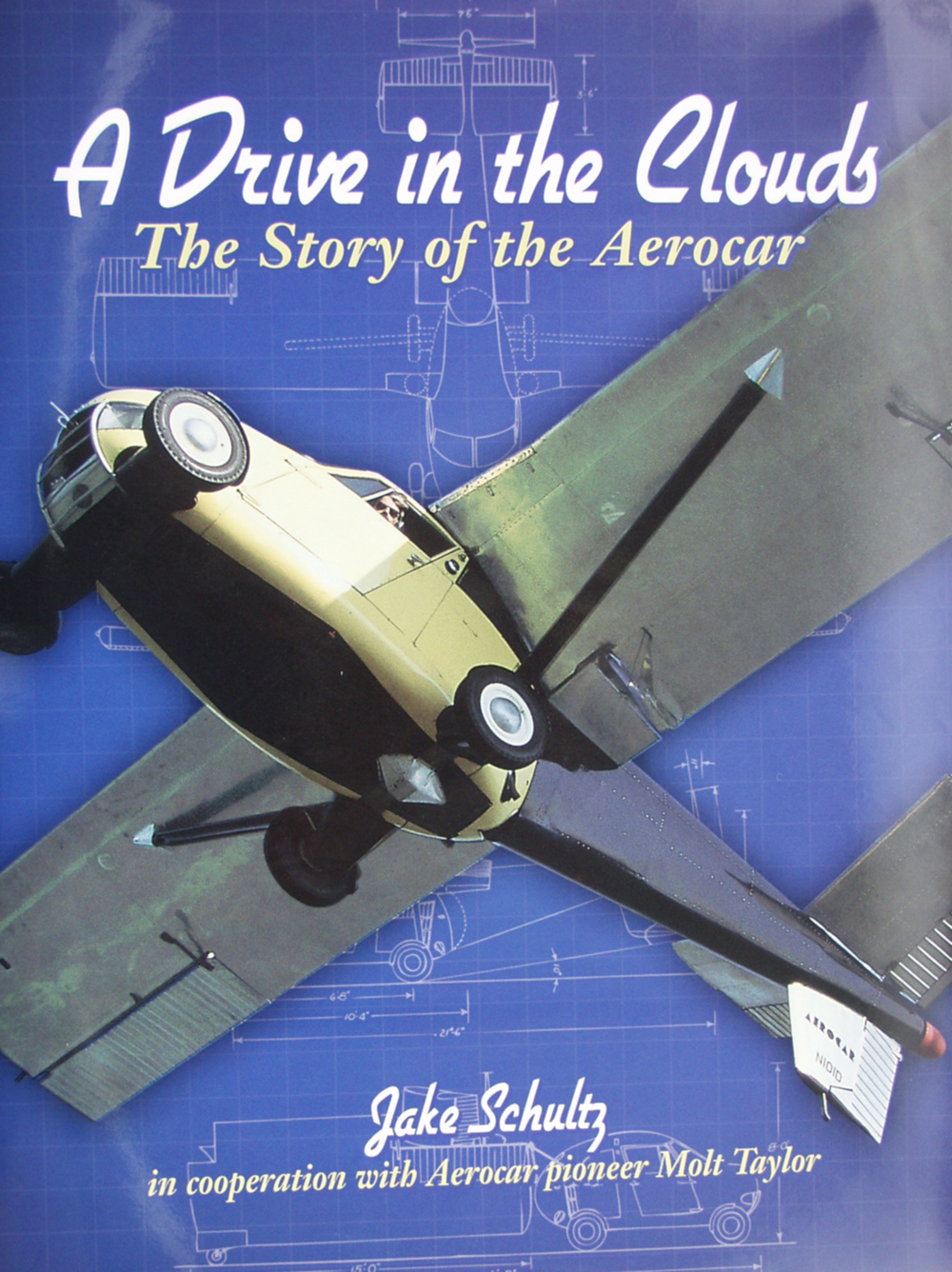

“A Drive in the Clouds” tells the history of the Aerocar and its inventor, Molt Taylor, of Longview, Wash.

By Terry Stephens

Traffic congestion on today’s highways has inspired more than one trapped motorist to wish their car could just fly over all of that gridlock. “A Drive in the Clouds: the Story of the Aerocar,” a book by Jake Schultz that was recently released, captures the fascinating story of a man who had that same dream and did something about it.

The late Molt Taylor designed and built the Aerocar, five models of car-and-plane hybrids that all flew and all exist today. This book about how Taylor’s dream became a reality—and why people still can’t fly over gridlocked traffic in their own vehicles—shows how much a dream can accomplish, and how the most surprising things can stall even the best of ideas.

In the mid-1940s, in Longview, Wash., Taylor began thinking about a sky full of flying automobiles that could quickly convert into road cars after landing. A Navy pilot and aeronautical engineer who once designed military drone aircraft and developed early versions of air launched cruise missiles, Taylor began experimenting with his Aerocar model in 1945 when he tested his first flying-car design in the University of Washington’s wind tunnel. At that time, one of the tunnel operators was famed aviator and X-15 pilot Scott Crossfield, who became good friends with Taylor and a lifelong supporter of the Aerocar concept.

After proving the feasibility of his model, Taylor moved on to full-scale development of his first Aerocar, planning and building for nearly four years before making his first flight over Longview on Dec. 8, 1949.

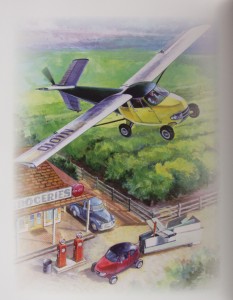

Taylor believed his vision of building a flying automobile that could soar above traffic jams on the nation’s two-lane highways, then return to the roadway at its destination, would promote aviation in new ways, appealing to people who had never dreamed of being able to fly—particularly in their own cars.

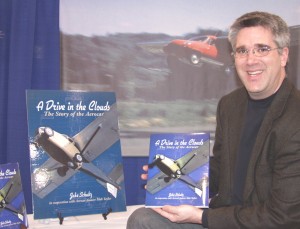

Part of the Boeing 787 production team in Everett, Wash., Jake Schultz has written the first book covering the history of the Aerocar and its inventor, Molt Taylor.

As his test flights continued, the locals began to notice. A few months and a few flights later, newsreel cameras began lining the runway to record the Aerocar’s soaring flights over the airfield and perfect four-point landings.

Soon, Taylor was demonstrating his flying car on a popular 1950s television show, “You Asked for It,” with host Art Baker. Driving the Aerocar on stage, Taylor showed off its car-like interior, the padded bench-seat equipped with two seat belts and a standard steering wheel. The dashboard held two sets of instruments: a speedometer and gas gauge for driving and an altimeter and compass for flying. Hooked to the rear of the car, like a trailer, were the folded wings and fuselage, with an inverted tail for the rudder.

Taylor told the television audience that the car’s four-cylinder, pressure air-cooled aircraft engine at the rear of the car also powered the Aerocar in flight. Unfolding and connecting the wings and tail took about five minutes. As an automobile, the Aerocar would easily reach 60 miles per hour, and flying as an airplane, it would cruise at around 100 miles per hour. If necessary, it could fly very high above traffic, to an altitude of 12,000 feet.

After Taylor’s presentation, the television cameras focused on a studio screen, which showed a recent film of Baker and Taylor at the local airport attaching the fuselage and wings to the Aerocar, buckling into their seat belts, taxiing down the runway, taking off, flying past the camera, landing and then converting the airplane back into a land motor vehicle.

Five Aerocars flew but the project crashed

Navy pilot and aeronautics engineer Molt Taylor hoped his Aerocar would revolutionize civil aviation across America, but production problems ended his dream.

For years, photos of the unusual Aerocar in flight generated extensive media coverage. The plane was featured in scores of magazines, including a 1961 Popular Mechanics cover story. From “You Asked for It” to “The Tonight Show,” promotion of the Aerocar seemed to be everywhere. In the early 1960s, television star Bob Cummings bought one. He liked the car-plane so much that he even worked it into several scripts for his comedy show.

Despite building and flying five models of the Aerocar, Taylor was never able to find the success he wanted. The vehicle attracted numerous supporters and buyers, but the burden of new government automobile regulations cost him the interest of Ford Motor Co., just as the giant auto manufacturer was about to launch sales of the Aerocar at its 4,000 dealerships.

Discouraged, Taylor gave up promoting his Aerocar, turning instead to designing sport-aircraft kits at his home and business in Longview, where he had designed, built and flown all of his revolutionary Aerocars.

It was the sale of those kit planes that connected him with Jake Schultz, a technical analyst on Boeing’s 787 program in Everett. Schultz had bought one of the kits and drove several hours south to Longview to pick it up in 1992. While talking with Taylor, Schultz became fascinated by the Aerocar saga. He visited the inventor several times, and the two men became good friends.

“In his preparation for closing his shop, I helped him sort through his documents and drawings for the Aerocar,” Schultz said. “I became keenly aware that all of his records were complete, right there in one place. I thought someone should do something to preserve them.”

For a few weeks, Schultz carefully considered taking on the daunting task of writing a book about Molt Taylor and his Aerocar.

“I had written primarily magazine articles before that,” he said. “But on my next visit, I offered to write a book on Taylor’s behalf. He gratefully accepted and we began our work.”

Molt Taylor shows off one of five Aerocars built at this factory in Longview, Wash.; all five can be found today at air museums or with private owners.

Taylor immediately went to a closet and began bringing out his drawings, handwritten notes, photos, negatives, Kodachrome slides and correspondence. Much of the material he discussed had never been covered in the hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles and numerous television programs that had featured the Aerocar.

Drawing on intense research from those records and rare interviews with the inventor, “A Drive in the Clouds: The Story of the Aerocar” documents the history, the people and the technology surrounding the Aerocar. One chapter in the book also explores other past and present inventors’ dreams of creating hybrid flying cars that perform as well on the road as in the sky.

This colorful book offers an unequaled collection of pictures and anecdotes, as well as the inventor’s intentions and insight into one of the most intriguing segments of American civil aviation history. In fact, Taylor’s pioneering efforts eventually led to his induction into the Experimental Aircraft Association’s Hall of Fame a few days before his death in 1995.

“A Drive in the Clouds” captures Aerocar history

Actor Bob Cummings, who bought one of the early Aerocars, loved to drive and fly it so much that he had it written into several of the scripts for his television show in the 1950s.

Schultz explained that Taylor told him the whole story of how the amazing vehicle was designed, built and flown, how it captured people’s imaginations and how the entire project became the victim of federal regulation.

“Ironically, the restrictive standards that grounded the Aerocar weren’t for aircraft but for automobiles,” Schultz said.

For more than 13 years, Schultz worked on the Aerocar story, which he published in January. During the course of his work, Schultz developed a great respect for Taylor’s vision and perseverance.

“I felt a real responsibility to tell his story before all of that material was scattered and lost,” he said. “I wanted to present Taylor’s dream about the Aerocar but also portray the kind of man and inventor he was. He had so much energy, so many ideas and so much humor.”

Another admirer of Taylor’s work is Paul Poberezny, EAA founder and chairman of the board. He wrote in the book’s foreword that Molt Taylor was a skilled engineer with a love for flying and a true experimenter who inspired future generations of inventors.

Today, Taylor’s Aerocar prototype is prominently displayed at the EAA’s AirVenture Museum in Oshkosh, Wis. The other Aerocars can still be found today, parceled out among private owners and aviation museums, including one on permanent display at Seattle’s Museum of Flight and another at Golden Wings Museum in Blaine, Minn., where it’s still flown occasionally by the museum owners.

Photos in “A Drive in the Clouds” show driver and pilot views through the windshield of the Aerocar, which provides a car steering wheel for both road and flight travel.

The remaining two car-planes are in Colorado. Grand Junction auto collector Marilyn Felling owns one and is looking for a buyer. Priced at $3.5 million, her model once flew traffic watches over Portland, Ore., but hasn’t been airborne since 1977. The other one, the last Aerocar built, is in Black Forest. Intrigued by the Aerocar, Ed Sweeney bought it in 1988, after taking a flight with Taylor, and still flies it at EAA AirVenture and other air shows around the country.

Schultz, too, had his chance to fly one out of Boeing Field (BFI) during the years he was researching his book on Taylor’s amazing engineering concept.

“I loved it; I was grinning ear-to-ear,” he said. “It didn’t have a lot of muffling on the engine, so it was a little loud. The concept, though, was great. You could drive it around like a normal car, attach the wings and tail if you wanted to fly somewhere, then land and drive again. It’s the most successful flying car ever built.”

Time to pass the torch

The prototype Aerocar, on an early flight over Longview, Wash., soon drew attention from news media film crews who contributed to the car-plane’s early popularity.

In his introduction to “A Drive in the Clouds,” Taylor wrote that he had spent the majority of his professional life and much of his personal resources and stockholders’ capital trying to introduce the concept of a flying automobile.

“I now feel that we can at least give a good accounting for the reasons we were not successful in our original objectives and suggest a possible future for the concept,” he wrote.

Successfully launching the Aerocar into America’s aviation and auto markets simultaneously certainly didn’t fail for lack of publicity efforts by Taylor, who proved to be a natural marketer at heart. Those who bought early models of his flying car eagerly helped in the publicity.

One of the most successful promotions came in the early 1960s when a Portland radio station used its Aerocar for a year for “Operation Air Watch.” The station’s promotion slogan stated that the Aerocar knew the traffic, because it had been there.

KISN logged 1,300 hours with the Aerocar, including memorable hours when it was airborne during the sudden 1962 Columbus Day windstorm. Buffeting winds devastated the Pacific Northwest that day blew the Aerocar backward, as it flew crosswind of the storm, heading for Hillsboro Airport (HIO) 14 miles away. The pilot watched the sights below, as roofs were ripped off buildings by the 100 mph winds.

While trying to land against 70 mph ground winds, the Aerocar’s airspeed wavered between 0 and 120 mph, as gusts repeatedly reversed its course. Suddenly, a downdraft plunged the plane toward the runway, then calmed just in time to allow the plane to pull out only 150 feet above the airport. Landing almost vertically at full throttle, the Aerocar’s four wheels came to an abrupt halt in the mud and grass adjacent to the runway.

After the storm, a tally found 56 light aircraft were heavily damaged at the airport, 16 planes were blown out of hangars and a twin-engine Beech was thrown across the field and became a pile of rubble on the runway. The Aerocar, however, suffered no structural damage, either in the air or on the ground, and by the next morning, it was flying its usual traffic-spotting mission.

Aerocar production came close, twice

Despite many successful efforts to sell and promote the Aerocar, Taylor’s dream of thousands of cars across the country being able to fly above traffic jams and park in private garages instead of hangars never came to be.

“At one time, Molt came close to having Texas aircraft manufacturer Ling-Temco produce 1,000 Aerocars,” he said. “But orders fell short of the number needed to start production.”

Then Lee Iacocca, then CEO of Ford Motor Co., showed interest.

“He assigned senior representatives of the product development staff to review the flying-car concept and estimate its popularity in the market place,” Schultz said. “The company’s survey found a potential for selling 25,000 Aerocars a year through its 4,000 Ford dealerships.

Certifying the Aerocar as a plane had already been accomplished. To further the deal with Ford, Taylor approached federal transportation authorities for certification of the Aerocar. But, they insisted he comply with all of the new environmental regulations being levied on the auto industry that year. Adding the prohibitive cost and complexity of meeting the new federal standards for noise, air pollution, fuel economy, mufflers and windshields cooled the ardor Ford officials had once had for the car-plane concept. With that insurmountable barrier, Taylor’s unique venture ended.

The dream of flying cars lives on

Schultz believes others may continue working to fulfill Taylor’s dream. In fact, one of the last chapters in his book explores the future of flying cars and the recurring vision that refuses to entirely fade away. He looks back at earlier attempts such as the Plane-Auto, SkyCar, ConvAIRCAR, Airphibian, Whirl Wing and Arrowbile, and then explores some thoughts about what happens next.

“Flying cars have tantalized people’s imaginations in movies such as ‘Chitty Chitty Bang Bang,’ ‘Back To The Future,’ ‘The Jetsons’ and ‘The Absent-Minded Professor,'” he said, adding that the effort to fulfill the dream sparked by Taylor’s Aerocar successes continues with such inventors and promoters as Colorado’s Ed Sweeney.

Working slowly but diligently in his retirement, Sweeney has been developing a modern version of Taylor’s vehicle, the Aerocar 2000. His design is based on a two-seat Lotus Elise that can be converted to add wings and a tail for flight. Inside the aluminum and fiberglass vehicle will be modern avionics for its flying mode. Sweeney said he expects to be flying the new car-plane in about two years.

As for Schultz, even though more than 1,000 copies of “A Drive in the Clouds” have sold in the first few months since it hit the marketplace, he’s not looking for a fortune from book sales.

“My greatest pleasure from the whole project has been succeeding as an aviation historian who has preserved an unusual chapter in American aviation,” he said.

“A Drive in the Clouds: The Story of the Aerocar,” published by Flying Books International, is available at the Future of Flight Aviation Center at Paine Field, the Museum of Flight at Boeing Field and Boeing Stores or by contacting the distributor at [http://www.historicaviation.com]. Contact Jake Schultz at jake.schultz@att.net.