By J. Ron Dickson

Surrounded by commercial buildings on land now owned by the Walt Disney Company, an empty ghost of a building sits—a building that was once the premier air terminal in the Los Angeles area. Glendale’s Grand Central Air Terminal was the official airport for Los Angeles, before Burbank’s United Airport and that bean field down in Inglewood called Mines Field (LAX) were built.

Located between the Los Angeles River (mostly dry, occasionally flooded) and San Fernando Road, just over the hill from the Hollywood land sign, the City of Glendale, Calif. (incorporated in 1906) was an early adopter of the new business of aviation.

It started with the Glendale Airport

In 1922—with prompting from the Aero Club of California, returning World War I pilots and local aviation enthusiasts who wanted to get in on the exciting new world of flying—the Glendale Chamber of Commerce purchased 33 acres adjacent to the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks, directly across the river from the Griffith Airdrome. They cleared a 1,200-ft. runway for the Glendale Municipal Airport. It opened in March 1923.

Soon after clearing the field, objections were raised for the City’s plans, and a bond issue was unsuccessful, so citizen supporters, led by Dr. Thomas Young, got together to form the Glendale Airport Association. This group bought the City out, and Glendale finally had an official airport.

The first hangar built at Glendale Airport was for the Kinner Airplane & Motor Corporation. Bert Kinner built Amelia Earhart’s first airplane, the Kinner Airster, in 1923. He also manufactured the first government-certified aircraft engine in 1928.

Early flying in Glendale

As early as 1906, citizens in the Glendale area had witnessed Roy Knabenshue (America’s first dirigible pilot and the manager of the Wright brothers’ flying team) flying his dirigible named California Arrow over the foothills of the Verdugo Mountains. Knabenshue had plans for regular airship trips from Pasadena to downtown Los Angeles and even accomplished a few flights, making his operation the first air passenger service in the country.

In 1912, the Griffith family donated acreage alongside the Los Angeles River to the Aero Club of California to be used as an area in which to promote flying. Enthusiasts were immediately attracted to this level, sandy flat inside a sharp curve of the Los Angeles River. Although technically outside Glendale’s border, but really just a hop across the mostly dry Los Angeles River, everyone in the hills of the city could look down on “their airport.”

Glenn Martin established an aircraft factory there in 1912, and he used the field for flight operations and manufacturing. In 1915, recognizing the shortage of good engineers in the still under-developed southern California area, Martin wrote to MIT professor Jerome Hunsaker asking for help.

Hunsaker recommended a young (but very bright) student assistant named Donald Wills Douglas. Douglas came out to the Glendale plant and was surprised to see how primitive Martin’s design and testing program was. Douglas introduced Martin to engineering and technical testing principals from the new world of aircraft structural design.

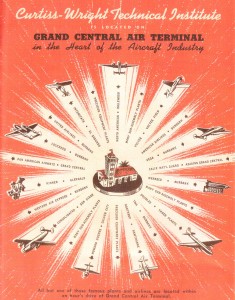

Curtiss-Wright Technical Institute is located on the Grand Central Air Terminal in the heart of the Aircraft Industry. All but one of these famous plants and airlines are within an hour’s drive of Grand Central Air Terminal

Floyd Smith was Martin’s chief test pilot. Smith and his wife, Hilder, flew stunts and parachute drops over Griffith Field.

A Washington state lumberman named William Boeing came to learn to fly at Griffith Park Airdrome. Boeing ordered a Martin bi-plane with pontoons added and had it shipped to his home in Seattle.

A wealthy Glendale real estate developer, Leslie C. Brand, looked down on the Los Angeles (Griffith Park) airport from his estate in the Verdugo Mountains (now the Brand Library). Seeing the flying activity below, he desperately wanted to fly himself. In 1919, he hired Waldo Waterman to build an airplane powerful enough to fulfill his dream of flying from his Glendale doorstep to his ranch at Mono Lake, Calif.

On April Fools Day 1921, Brand held the first “fly-in” party—no one was allowed entrance except by air. Landing on the steeply sloped area in front of the Brand home was tricky, but over 100 people arrived safely by airplane including film stars, business tycoons and military pilots from all over southern California.

Bill Waterhouse and Lloyd Royer built the Romair bi-plane for Pacific Air Transport and the Cruizair monoplane at Glendale Airport. The Cruizair drawings were purchased by T.C. Ryan in San Diego and were modified into The Spirit of St. Louis.

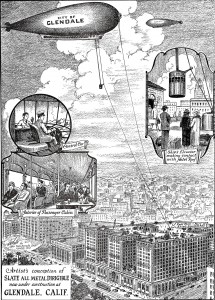

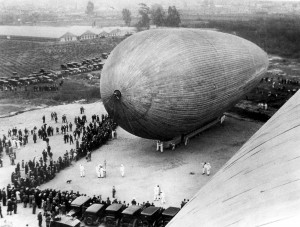

In 1926, Thomas B. Slate leased space at Glendale. The Slate Dirigible Company was organized to create a sheet metal dirigible made of ribbed and crimped aluminum panels. The craft was 212 feet long and 58 feet in diameter and was expected to carry a five-man crew and 35 passengers.

It had one small propeller on the nose driven by a steam engine. The principle was that air would flow over the teardrop shape and create forward motion. The ship was christened The City of Glendale in December 1929. When rolled out of its hangar in January 1929, the sun hit one side, heating up the metal and distorting it enough to burst a seam and cause it to lose lifting gas—a deadend on the evolutionary trail of aviation.

Maj. Corlis C. Moseley had established the 115th Observation Squadron, 40th Division Air Service at Clover Field in Santa Monica in April 1924. Lacking proper armory and training facilities, Moseley (or “Mose” as he was often called) found the abandoned airfield at Griffith Park and decided to make it his own. He had to fight the City of Los Angeles—it wanted to build a golf course there, but he won the battle.

In October 1924, he received permission from the Board of Park Commissioners to establish a “flying operations base” there. One of the board members was Van Griffith, the man who had originally donated the land to the Aero Club of California in 1911. This was the first unit of the National Guard, and because of its relaxed atmosphere and its proximity to Hollywood, it was considered by some to be a country club for the air services.

The California Air National Guard (CANG) used the field until March 1941, when they were activated for the war and sent to Paso Robles, Calif. They reorganized at Van Nuys Airport in 1946 as the 115th Bombardment Squadron. Their stay at spacious VNY was short—in April 1948, the unit was relocated to the southwest corner of Lockheed Air Terminal in Burbank where they joined the 62nd Air Wing. In 1950, the 62nd was replaced by the 146th Composite Wing, which is still the command wing for the 115th today. In January 1960, the 115th (along with the 146th) moved back to VNY. They are now at the Channel Island Air National Guard base, which is built on the North end of the Point Mugu Naval Air Staiton.

Jack Northrop came to Glendale in 1927 after working for the Lougheed brothers in Santa Barbara. Northrop was developing metal wing structures, replacing the wood and cloth commonly used. Using “multi-cellular” metal construction design, his Avion Company made a prototype called the Avion EX-1. This novel aircraft (mostly wing with twin trailing booms) was the forerunner to Northrop’s flying wings of the late 1940s. When test flown by Eddie Bellande, it demonstrated that, as Northrop said, “The cleaner the airplane, the better it will fly.”

In 1927, Zenith Aircraft Corporation built the Albatross. With a wing span of 90 feet, it was the largest aircraft in the West.

Wally and Otto Timm, in 1928, had a shop near the airport. They built aircraft for Al Wilson to use in movie shoots, and they also modified aircraft for use in the Howard Hughes film “Hell’s Angels.” They built the Golden Shell Special for Shell Oil and the Collegiate, a two-place, high-wing monoplane.

A short distance up San Fernando Road from Glendale Airport, Al Menasco established a business rebuilding WWI surplus engines. Menasco’s own Pirate engines would soon make history in the air racing arena, and his company would eventually make landing gear and assemblies for Lockheed and other companies.

When Menasco brought his friend, William Boeing, over to see Northrop’s work at Glendale in 1930, Boeing was impressed and purchased Northrop’s Avion company. Boeing moved the business to the new United Airport in Burbank.

Cal-Aero Academy purchases Grand Central Airport from Curtiss-Wright Corporation of New York. Cal-Aero Technical Institute is recognized as one of the best CAA approved technical schools of aviation n the country – August 1944

Grand Central Air Terminal

In 1929, Glendale Airport was purchased by investors, enlarged to 175 acres and reorganized to become Grand Central Air Terminal (GCAT), the first well-funded, dedicated commercial airport in the West. GCAT was to become:

• the western birthplace of the scheduled airlines,

• an operational P-38 fighter base during WWII,

• a source of thousands of pilots and mechanics for WWII and the Korean War,

• the western source for Curtiss-Wright engines, and

• a service and refurbishment center for thousands of surplus aircraft.

GCAT opened on Feb. 22, 1929, with a single 3,800-ft. concrete runway aligned with the prevailing northwest/southeast winds, the first concrete runway on the West Coast. It also had a grass area for crosswind landings. Among the original backers of GCAT were Charles Spicer and Jack Maddux of Maddux Airlines.

Opening day saw thousands of local citizens in attendance. As Glendale is only 15 minutes from the San Fernando Valley where the Hollywood elite maintained their ranches, the crowd included Tom Mix, Wallace Beery, Gary Cooper, Mary Pickford, Jean Harlow and many other elite. The governor of California, C.C. Young, was flown in by Roscoe Turner to mark the occasion.

Over the years, other Hollywood names would pass through Glendale, many learning to fly there. These included Jimmy Stewart, Clark Gable, Carole Lombard, Knute Rockne, Louis B. Mayer, Mary Aster, Jack Warner and Charlie Chaplin.

In May 1927, Charles Lindbergh made his solo flight across the Atlantic, and the world caught fire with aviation madness. The Spirit of St. Louis that Lindbergh flew was based on plans of the Cruizair originally designed by Waterhouse & Royer at Glendale Airport in 1926.

The terminal building

The terminal building at Grand Central was designed by Henry L. Gogerty in the Spanish Colonial Revival style with zigzag modern elements. It was a large and beautiful two story structure with direct access to the ramp. Its elegant lighting and metal railings were works of art, and decorative plaster detailing made the inside shine. There were colorful tiles set into the stucco, the roof was red Spanish tile and pristene landscaping and lighting made for a rich atmosphere.

It had ticketing, a sandwich shop and coffee counter and a check room and waiting area on the first floor. Large arches lined the runway side of the building while visitors watched the aircraft come and go. Upstairs was a fine dining room, offices and another large waiting room with an even greater view of the airport and the San Fernando Valley farmland.

There were several long hangars running south from the terminal building. Two of those hangars remain today—one has been repurposed as a frozen food service and the other is used by Walt Disney Imagineering to work on new ride systems and effects.

Breakfast Club

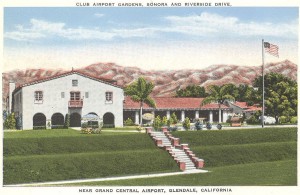

There was a two story Spanish hacienda-style building constructed across the field in the southwest corner of the airport, just a few hundred feet from the Los Angeles River. Imagine the large dance floor, a swimming pool, palm trees and shade on the verandas and tennis courts. It was a perfect place for the elite to meet, close to air activity, but definitely for the upper crust. There were rumors of a tunnel leading from this party palace to the banks of the river, something to do with possible liquor and gambling activities during the Prohibition era.

The aviation business was evolving quickly in the late 1920s. The Curtiss Airport Corporation, heavily capitalized by the Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Company, was purchasing airports across the nation in preparation for the new passenger air age. By May 1929, GCAT was owned by Curtiss Airport Corp. When the Wright Aeronautical Corporation finally ended a 20-year battle with the Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Company, they joined forces to form Curtiss-Wright Corporation. Within months of its opening, Grand Central Air Terminal was owned by Curtiss-Wright.

The company operating the airport was named Curtiss Flying Service, managed by Maj. C.C. Moseley. Moseley had been managing Curtiss operations in the western states and became the leading figure at Grand Central until its demise.

Birth of the scheduled airlines

Grand Central technicians constructed mobile training units to be flown to combat theaters all over the globe. These units were made of aircraft parts and were used to show pilots and crew members proper proceedures and how systems worked.

With a reliable airport, a modern terminal building, and larger, safer aircraft, adventurous individuals were scrambling to establish air service from Glendale to various locations in the West. This was the beginning of scheduled and reliable air service in the western states.

One of the earliest efforts was Western Air Express, incorporated in July 1925 by Moseley and Harris “Pop” Hanshue to fly from Los Angeles to Salt Lake City. They set up at Vale, then Alhambra, Glendale and Burbank.

The Curtiss-Keys Group, the Wright Aeronautical Company, the Pennsylvania Railroad and some St. Louis bankers came together to form Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT) in May 1928. They established a combined airplane and train trip across the country which could take up to 48 hours to complete.

Charles Lindbergh was technical advisor for TAT. As he surveyed possible routes for them, he chose Glendale as their western base. Lindbergh flew the first scheduled passenger flight from west to east from Grand Central in July 1929, flying for “The Lindbergh Line.”

Curtis-Wright Technical Institue offered an Aeronautical Engineering Degree in 14 months and a Master Aviation Mechanic Degree in one year (February 1941).

Jack Maddux, a car dealer in Los Angeles, created Maddux Airlines and began flying between Los Angeles and San Diego in Ford Tri-motors in July 1929. Later he would include flights to Aqua Caliente, Mexico and San Francisco. Maddux was the first to use multi-engine aircraft, adding greatly to the public’s confidence in flying.

In November 1929, Maddux Airlines merged with TAT to become TAT-Maddux, with Jack Maddux in charge of western interests.

The government was getting involved in all this also. In 1930, the Watres Act authorized Postmaster Gen. Walter Folger Brown to merge airmail routes down to just three, with one company flying each route. His decree caused TAT-Maddux and Western Air Express to merge into one entity and Transcontinental & Western Air (TWA) was born.

Pickwick Stage Systems, an established busline to San Francisco, introduced airline service from Los Angeles to San Diego in March 1929, flying Bach Air Yacht tri-motor planes. They added a San Francisco run in May 1929.

The fastest airline of the time was Nevada Airlines. This specialty air service was the dream of Carl Squire of Lockheed, and it flew the Lockheed Vega, which was the fastest passenger ship of the day.

The first run was from Glendale to Reno, Nev. Later they added flights to Las Vegas and Tonopah. Nevada Airlines only lasted for a short time—too few travelers would pay $50 per flight only to suffer landing on dirt fields and stay in barely adequate overnight accommodations. Its pilots included race pilot and self-made celebrity Roscoe Turner, with Marshall Headle and Wiley Post (both Lockheed test pilots) making occasional runs.

Hawley Bowlus had worked on The Spirit of St. Louis at Ryan. He eventually ran the mechanics school at Grand Central and was the first American to master the art of soaring. He designed and built sailplanes and home-built glider kits.

Many movies were shot at Grand Central including “Bright Eyes,” “Sky Giant” and “Central Airport.” Other local movie sites were the United Airport in Burbank, with Wilson Aero Service just to the west; Metropolitan Airport in Van Nuys; and Caddo Field, site of Howard Hughes filming of “Hell’s Angels” just west of VNY.

In 1927, Roy Wilson was a movie stunt pilot, and his brother Tave flew camera ships for movie makers. They worked from Glendale Airport, and some of their hired help included Frank Clarke, one of Hollywood’s most fearless stunt flyers, and Roscoe Turner. As with anyone else in aviation at this time, they were involved in Hughes “Hell’s Angels” movie shoot.

Varney Speed Lanes (or Lines) flew the Lockheed Orion to San Francisco. They could top 230 mph and were the fastest ships available in 1932.

By 1932, Joe Plosser had established the Grand Central Flying School in the northwest corner of the field, away from the more stable airline operations. Students at “Plosserville” included Howard Hughes and Douglas “Wrong Way” Corrigan, who learned instrument flying there. Edgar Bergen and Errol Flynn (from the Hollywood group) also learned how to fly from Plosser.

Howard Hughes set up in a small building on the edge of Grand Central Airport in 1934. He and Dick Palmer, with a crew of Cal-Tech engineers, began work on the Hughes A-1 Racer. They used the Guggenheim Wind Tunnel at Cal-Tech (formerly the Throop College of Technology) in Pasadena. In 1935, Hughes set a speed record of 352 mph in the sleek new racer.

Moseley leased the field in 1934 from the corporate owners and began operations under the name Aircraft Industries Company. Later he purchased the airport outright and changed the name from Curtiss-Wright Technical Institute to Cal-Aero Technical Institute.

In 1937, Hughes set a transcontinental record of seven hours, 28 minutes from Glendale to New York, a record that would stand against all other aircraft including military for the next decade. This small, secretive organization at Grand Central was the beginning of Hughes Aircraft.

Hughes flew the Lockheed Model 14 Special around the world in 91 hours for a new record in 1938. He landed at Glendale.

Hughes then leased Jacqueline Cochran’s Northrop Gamma and installed a new Wright Cyclone-G 1,000-hp engine at his own expense. From John Underwood’s book “Madcaps, Millionairs, Mose,” after winning a bet by flying from a lunch in Chicago to a dinner in California, “Eight hours and 10 minutes later he landed at Glendale utterly exhausted. Hughes heaved himself out of the cockpit, shuffled wearily to the terminal dining room and ordered a hamburger and a bowl of soup.”

Prewar

The Civil Aeronautics Administration started the Civilian Pilot Training Program in 1938 to create college-educated aviators. Glendale College was among the first schools chosen. Their program was started by Huston Crawford in 1929 and lasted for 60 years until it closed in 1989. The Vintage Aeroplane Association of California still has monthly meetings at Glendale College, even though the two-year A/E program ended a few years ago.

As the Battle of Britain decimated the Royal Air Force, Americans trained in Glendale joined up to fly in the Eagle Squadron in defense of England, all while America was still officially isolationist and uninvolved.

In 1939, Maj. Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold’s Army Air Corps asked Mose to organize civilian contract schools to train pilots. Using Plosser’s flying school as a start, Mose established a 12-week flying course through the Grand Central Flying School (GCFS) which later evolved into the Cal-Aero Flight Academy (CAFA). Cal-Aero established schools at three locations: Cal-Aero at Ontario, Mira Loma at Oxnard and Polaris at War Eagle Field near Lancaster in the Antelope Valley north of Los Angeles.

Thousands of pilots and mechanics learned their trade at the Glendale field, with ground school provided by Glendale Junior College. They flew training missions all over the western San Fernando Valley, which was largely farmland and very sparsely populated. As flights increased, trouble with their neighbors began.

According to Underwood’s book “Madcaps, Millionairs & Mose” (page 109), movie studio moguls complained about airplane noise spooking their high-blooded horses and interrupting their shoots. Farmers claimed their chickens were laying fewer eggs. Defending the noises as the sounds of “the birth of an air force vital to our national well-being” did not stop the outcry. By 1941, practice flying had been moved over the hills to the less developed Newhall area.

When Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941, Grand Central Airport was immediately closed to civilian aviation, along with all other West Coast airports. The Army Air Corps established an important defense base for Los Angeles at Glendale, and the airport was painted to look like streets, fields and houses from the air. For pilots, this made landing very challenging, especially in the hazy air of Los Angeles.

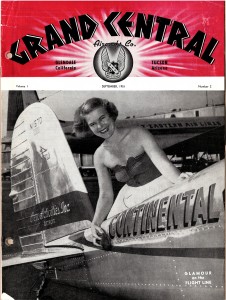

Grand Central captured the essence of the aviation community. Grand Central Aircraft Company – September 1951

The 318th Fighter Wing was stationed and trained there for the immediate protection of the Los Angeles area. Barracks and concrete revetments were built on the west side of the airport near the former home of the Aero Club Southern California.

The single concrete runway (which originally ended at Sonora Ave.) was lengthened to Western Ave. (adding 1,200 feet to the original 3,800 feet) to accommodate the hot new P-38 fighters coming over from Lockheed Air Terminal, just four miles away in Burbank.

The Los Angeles Air Raid occurred one night in 1942, sending bullets and tracers up and into the air over a nervous city.

Not long after the Pearl Harbor attack, 40 Wright R2600 engines were received at Cal-Aero for inspection and modification. Unknown at the time, those engines powered Doolittle’s Raiders on their mission to Tokyo early in WWII.

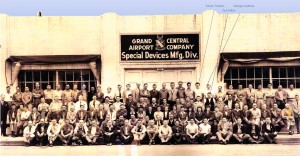

Grand Central technicians constructed mobile training units for the Western Technical Training Command to be flown to combat theaters all over the globe. George Crabtree, a long-time employee of the Specialty Devices Manufacturing Division at Glendale, describes designing and building rolling boards with schematic systems built of actual parts from aircraft, but with truncated lines and cables. He added graphics to describe just how the various parts and pieces worked. These were a great aid to pilots and crew members while trying to learn proper procedures—better done on the ground than in the air.

With pilot and mechanic training, aircraft repairs, special government and production projects, and the operational defensive air base, Grand Central was a 24-hour a day operation throughout WWII.

After WWII

As the war was winding down, Moseley purchased the airport from Curtiss-Wright in 1944. GCAT became Grand Central Airport (GCA). Curtiss-Wright Technical Institute, having finished its Air Corps training mission, became Cal-Aero Technical Institute, and Moseley established the Grand Central Aircraft Company

Grand Central Air Terminal was home to these and many other companies. It was the hub of aviation in southern California.

In 1947, Glendale City civic leaders shortened Grand Central’s runway to its prewar length, limiting newer and larger aircraft from landing there and relegating the field to civil aviation and non-scheduled airline work. The largest aircraft ever to land at Grand Central was a Lockheed Constellation.

After the war, thousands of P-51s, C-47s, B-25s and other aircraft transitioned through Grand Central Airport for updating and refurbishment. Accounts included the Nationalist Chinese Air Force, the Brazilian Aeronautical Commission, Uruguayan Air Mission, Standard Oil, Sinclair Oil and airlines too numerous to mention. The fields limited runway length would be its eventual demise.

The Korean Conflict

In 1950, Grand Central Aircraft Company leased two hangars at Tucson Municipal Airport in Arizona to rebuild the larger aircraft required for the Korean War. Jets and large aircraft (like the B-29) were sent to the Grand Central Service Center in Tucson, Ariz. Grand Central (in both locations) was recognized as the largest repair, overhaul and modification station in the country. With the end of the Korean War, the end of Grand Central, Glendale, was near.

The airport was relegated to private flyers and occasional emergency landings. The Sports Car Club of America sponsored races a few times during the 1960s. Lance Reventlows’ beautiful Scarab debuted there.

In 1955, Moseley formed the Grand Central Rocket Company to test solid rocket propellants in the dirt behind old concrete revetments left around the field. This effort became a sizeable producer of successful rocket fuels and was eventually sold off to become the Lockheed Propulsion Company. The old airport facility was too small to be current; the area was now completely surrounded by homes and businesses. The airport was closed in 1959.

An airport’s demise

The runways were torn out and replaced by a street named Grand Central Avenue. Over 70 new “tilt up” manufacturing buildings were constructed under the direction of the Grand Central Industrial Centre, whose chairman of the board and president was Moseley.

The redeveloped airport property was eventually purchased by the Prudential Insurance Company and leased out as an investment.

When Walt Disney was developing Disneyland in the early 1950s, he wanted a place away from the main studio where he could work on new ideas undisturbed. He rented an industrial building at 1401 Flower St. on the old airport property. WED (Walter E. Disney) Enterprises also rented the old terminal building during the busy years of Epcot and Disney World development.

Dreamworks was created in 1994, and their new buildings soon appeared on part of the old airport land just down the street from Disney’s leased building. The Disney Corporation soon purchased the remaining land from the airport and have announced a 15-year plan to turn it into a corporate “creative campus” behind security gates.

Disney has stated their intention to rework the old terminal by the year 2015 to its original look. Much of the original metal work, railings and lights have been stripped away over the years, but the Disney representative feels that their company can easily reproduce replacement pieces.

There are also two original hangars left—one very modified into a cold storage facility and the other is now used by Disney Imagineering for special effects mock-ups. These building are not mentioned in any proposals to preserve our aviation history.

The Grand Central Airport terminal building is still there at 1310 Air Way St., between Sonora and Grandview Ave. in Glendale, along with two original hangars a few blocks away. For many years, the terminal building sat abandoned, a curiosity from the past. There were holes in the roof and open windows allowing unauthorized access.

The Glendale Historical Society met with Don Chuchla, Disney’s project manager for the old airport area, in 2002 and pressed for action to prevent further deterioration or accidental loss by fire. The company acted quickly to preserve the building in a state of arrested decay and built a chain link fence around it. The building was damaged in the 1994 earthquake and is considered unsafe for inhabitants.

Most who know of the building assume that it is under the protection of the National Registry of Historical Landmarks. While it is on the Glendale City list of historical places, it has no Federal or State protection. When Disney was asked about applying for National Registry protection, they replied that they would only seek that listing after completing any restoration work.

There are only four aviation-related locations listed by the Historic Preservation Office of California. They are the Hamilton Hangar at Burbank (torn down in 1994); Hangar One at LAX; the Dominguez 1910 Airmeet site in Dominguez Hills, Calif. (the 100th anniversary is coming up in January 2010), and the Portal of the Folded Wings in Burbank.

The San Fernando Valley is also home to the following:

• Grand Central Air Terminal,

• United Airport (BUR—home of the Bendix Races),

• Metropolitan Airport (VNY),

• several Lockheed plants (the birthplace of the Lockheed Skunk Works),

• Pacific AirMotive,

• Bandi,

• Menasco,

• AirResearch,

• Marquardt,

• Rocketdyne

• and many more, is now bereft of historic aviation buildings and sites.

With the loss of the Casablanca Hangar at Van Nuys Airport a few years back, progress has succeeded in destroying nearly all of our great aviation historical sites. The Grand Central Air Terminal building is the single remaining historic building from over 77 years of aviation history in the area. It would be the ideal place to establish an aviation history and research library representing the history of the San Fernando Valley.

About the author/ J. Ron Dickson

My father was a model and pattern maker for various industries in the San Fernando Valley area. He worked for companies like Lockheed, Space Labs, Cal-Tech, Xerox and many others from 1947 until his death in 1971. He sent me all over the San Fernando Valley, picking up supplies, dropping off models, picking up drawings, etc. The shops I visited were making aircraft, race cars, baby strollers, movie camera mounts, mechanical special effects and props for the studios, rocket engines . you name it.

If it wasn’t made within an hour’s drive of Burbank, you didn’t need it. Disney, Warner Brothers and NBC were the big guys, but there were so many small shops turning out great stuff. And then there was Palley’s Surplus on San Fernando Road—oh, the pallets piled with Army stuff (the real stuff), the smell of cosmoline and canvas—what a wonderland for a kid!

It was a great and productive time in our history, and I miss the feeling I got from doing something real. Now that our country doesn’t do much hands-on fabrication, I miss the old days when a person with an idea could draw something up and start to make it. Aviators seem to be the most like those guys that I respected so much.

Now that I am a gray beard (born in 1947), I teach hands-on fabrication at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. The students wonder why they need to actually touch materials and work them with their hands in order to learn how to design. They believe the real world resides inside microchips and monitors. By comparison, I think I am of another world.

When I worked at Walt Disney Imagineering in 1991, I could still look up and see peeling paint that revealed portions of the hangar sign that said “Curtis-Wright Technical Institute.” Unfortunately, someone thought the historic peeling paint was an eyesore, so they power-washed the old paint and made everything an irritating, bright white. That’s the way some folks do “vintage aviation” out here in California.

There is one very important bit of aviation history here in Burbank, a very little known site even to our local citizens. I went there as a kid to catch pollywogs, but like many important things, I didn’t recognize its significance until much later in life.

It is called “The Portal of the Folded Wings,” and it is a shrine to aviation. It is located just south of the runway at BUR in Valhalla Memorial Park. It was built in 1924 as the entrance to the cemetery, with wonderful sculptures and colorful ceramic tiles. It is a 50-ft. square building with arches on each side over 70 feet tall. Pilots taking off south from Burbank fly directly over it, about a quarter of a mile from the airport fence.

It was dedicated to “the honored dead of aviation” in 1953 on the 50th anniversary of powered flight. The ashes of Walter Brookins, Roy Knabenshue and Charlie Taylor (all active members of the Wright Brothers flying team) are buried there.

Bert Acosta, Carl Squire, Bert Kinner, Matilde Moissant, Bobbi Trout and many others also lay in rest under the sounds of aircraft from Burbank airport. I do not want to see this last connection to our great aviation history in the area be lost.

J. Ron Dickson is a historian who, along with his long-time friend John Underwood, deserve immense credit for documenting all this information in several books over the years. Many sources and the Glendale Historical Society contributed as well. You can contact John at: JRDickson@Earthlink.net