By Fred “Crash” Blechman

Captain Ernie Bankey, “The Tiger of Bonn,” and his P-51 Mustang, “Lucky Lady VII.” The 17 symbols under the canopy represent the 17 aircraft he destroyed on the air and on the ground.

You’ve probably heard of the radio call by an American fighter pilot in World War II that began, “I’ve got 40 Messerschmitts cornered…”

The fact is, that was not exactly the way it was worded, according to retired Air Force Colonel Ernest E. Bankey Jr., who became an ace-in-a-day soon after making that famous radio call.

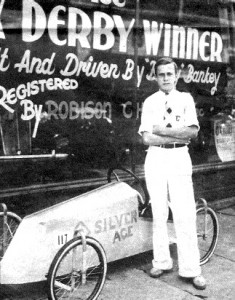

Ernie Bankey was born on Aug. 28, 1920, in Cleveland, Ohio, and raised in Toledo. A pilot friend-of-a-friend from Germany interested Bankey in flying, and starting at about eight years old, he went through years of building model airplanes. He was also the only youngster to win the Soap Box Derby in both 1935 and 1936 in Toledo.

Bankey’s mother passed away when he was nine years old.

“During the summer months, I would go to Cleveland and stay with my aunt. They were right next door to the Cleveland Air Races,” recalled Bankey. “I watched them flying around the pylons as a youngster, and I guess that stimulated me.”

Although he had never actually flown in an airplane, when he graduated from high school, Bankey wanted to fly, so he signed up with the Army Air Corps, on April 1, 1941.

“They wanted unmarried college graduates for pilot training,” he said. “I wasn’t a college graduate, but I wanted to be near airplanes, and I heard they were going to have staff sergeant pilots. I signed up so I could go to a mechanics school, but they were full, so I took my second choice, which was armament school.”

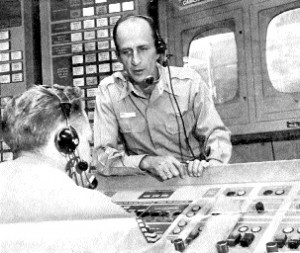

Official Air Force photo shows all five Atlas engines roaring at full power as it struggles upward from Vandenberg Air Force Base, where Ernie Bankey was site commander for the first military ICBM launch into the Pacific.

Working his way up to staff sergeant, Bankey taught aerial gunnery at Las Vegas, Nev., then applied for air cadet training. He flew primary flight training in the PT-13 Stearman at Tulare, Calif., then basic training in the Vultee BT-13 in Modesto, Calif., and advanced in the North American AT-6 in Phoenix.

He then trained in the twin-engine Curtiss AT-9, before transitioning into the Lockheed P-38 twin-engine fighter.

“The version of the P-38 we first flew was the RP-322,” he said. “It was a P-38 without the turbos (turbo superchargers for high-altitude flight). A flock of these aircraft was being built for the British. Although it was being built as a high-altitude interceptor with turbos for our people—two 1,200-horsepower Allison engines could get up in a hurry—somewhere along the line, they decided it could become a fighter without the turbos. The British refused them because it was not effective above 10,000 feet, so it became a training plane.”

Bankey earned his pilot wings and second lieutenant commission with class 43G at Williams Air Force Base in Arizona, in July 1943, and was assigned to the 383rd Fighter Squadron of the 364th Fighter Group for a month of gunnery and bombing training in the P-38 at Muroc, Calif. (now Edwards Air Force Base). Then they went to Van Nuys Airdrome, as Van Nuys Airport was then called.

“We were the first military on the base,” he said. “From there we would go over and pick up our aircraft at nearby Lockheed Aircraft, where the planes were being manufactured. We were at Van Nuys about 45 days, doing our training, flying formation and acrobatics, and were then assigned to Oxnard Flight Strip, which is Camarillo Airport today. We were there for about 45 days, doing more gunnery, bombing, and flying patrol over Los Angeles during a submarine scare.”

The 383rd Fighter Squadron then moved to Santa Maria Airport, where they joined with the other two air group squadrons (the 384th and the 385th).

“We left from there by train cross-country for five days,” Bankey relates, “and then we had our paperwork and physicals taken care of at Camp Shanks, New York. We left from New York Harbor on the Queen Elizabeth, with first class accommodations for five days, arriving at Liverpool, England, on the fifth of February, 1944. Then it was by train to Bury St. Edmunds, near Birmingham, and finally to where we were based, Honington Royal Air Force Base in East Anglia. It had pierced-steel planked runways, but the rest of the accommodations were first class—like permanent two-story stucco buildings with seven-foot tubs!”

Major Bankey in a Vandenberg Air Force Base control room for the launching of an Atlas ICBM Missile in 1961.

Bankey flew on the group’s third combat mission in a P-38, as well as the last in a North American P-51. He flew 110 sorties, with over 350 combat hours in the P-38 and 150 in the P-51. During two tours of duty (February to September 1944, and October 1944 to May 1945) he was reassigned to the 385th Fighter Squadron and the 364th Group Operations Section.

Bankey’s most memorable flight—and the one with the now famous quote—was on Dec. 27, 1944, during the “Battle of the Bulge,” Germany’s last major World War II attack. Bankey was flying his patched and battered P-51 Mustang, “Lucky Lady VII.”

According to Bankey, “We were getting our tails pushed back. The Germans were making a concentrated effort. The weather was so bad that no planes from England could get over there. But when it cleared there was an all-out effort by fighters. We were not directed to escort bombers; we were scheduled for a “rhubarb”—looking for targets of opportunity. I was flying with the 385th, but I was leading the 383rd squadron that day. I was a captain, and known in both squadrons.

“We spotted some 200-plus aircraft down below us who were giving ground support to the enemy and chopping up our guys, coming on in like waves. Seeing them, I gave directions quickly to the squadron: ‘Pick out your targets. Tally-ho!’ So we jumped the whole flock of them and they busted up. My wingman stayed with me through two victories—as I recall, they were (Messerschmitt) 109s—and then he lost me in the combat confusion.”

Bankey said he spotted three stragglers down below, identified them as 109s, dove down and picked out the leader.

“My policy is to get the lead and add confusion to the rest,” he said. “He exploded and the other two quickly separated. I followed one and I was surprised to get in on him because he made such a sharp turn, so I had to make a very sharp turn or go past him. Without seeing him, I figured he was underneath my nose at about 25 yards. I pulled my trigger while pulling about seven G’s and felt a large explosion underneath me. I winged up and, sure enough, my shells hit him, blew him up, and I went through his concussion.

“After that one I figured I better get out of there, so I climbed back up again, and that’s when I saw this whole gaggle of (Focke-Wulf radial-engine) FW 190s. The German forces usually flew in a V line—not like our type of four-plane formations. When I saw this line of 20-plus aircraft—they usually flew in 20s or 25s—I saw that they were flying with the sun behind, a fatal mistake. So I dove down on that line, intending to cut into the end of it. They saw me, gave it the gun, holding their positions, and started going down. I kept after them, and we got down pretty close to treetop level—at least steeple-level, because I was glancing where am I at on the ground. I was able to trigger-in on one.”

That was the fifth victory that day, making Bankey one of those rare “ace-in-a-day” fighter pilots.

Bankey was flying an inline engine P-51, and had not noticed about 25 inline engine planes behind him. The Germans ahead of him, looking back, thought that Bankey was a P-51 leading another 25 P-51s. Actually, the planes following Bankey, he soon realized, were German inline (Messerschmitt) Me 109s! Bankey was alone, sandwiched between two groups, each of about 25 German fighters!

This is when Bankey got on his radio and said, “This is Sunkist Two. I’ve got 50 Jerries cornered over Bonn. Will share same with any P-51s in the vicinity. See me at smokestack level. Over and out.”

“It was just one of those things. Anxiety, I guess, overruled my train of thought,” Bankey explained. “So it’s been quoted as 40, and that’s okay. But I figured there was a line of 25 front, 25 behind. I did get a relief quickly. A flight of four P-51s came down over my left wing. They had heard the call and saw the action.”

In the ensuing melee, he shared one more victory with another P-51, for a total of five and a half victories on one flight.

“After that, I started back home,” he continued. “I was low on ammo; I knew my fuel was coming down low with all the combat, so I found Y-87, our base up in Belgium. I landed and after the base commander treated me to a little Scotch, I refueled, and took off for home base. It was a mighty long flight, all by myself, with the sun going down. But hey! I was glad I was alive.”

For this mission, he earned the unofficial title of “The Tiger of Bonn.”

As of Dec. 1, 1946, mission reports credit Bankey with 10 and a half air-destroyed, one probable, five ground-destroyed, and five ground-damaged enemy aircraft. In addition, he is credited with the destruction of 44 locomotives. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for shooting down five and a half aircraft on one mission, when the group was awarded the Distinguished Unit Citation. Additional combat awards include the Silver Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross with Cluster, Air Medal with Nine Clusters, and the French Croix De Guerre with Palm.

Bankey left the service in January 1946, and was a general contractor until returning to the service in 1953. He served as fighter/bomber officer/chief USAF Europe, stationed in Germany and Libya, North Africa.

Assigned to Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, in August 1958, Bankey served as site commander for the first Intercontinental Ballistic Missile launch into the Pacific by an Air Force crew on Sept. 19, 1959.

“I was a major at that time,” he recalled. “We went down to Convair at San Diego for training on the five-story Atlas missile. After that first Atlas Vandenberg launch we became kind of the ‘daddies’ of the ICBMs. We wrote the book—”Air Force Regulation 80-14.” The atlas was later used in Florida as the booster for the Mercury and Gemini space flights.”

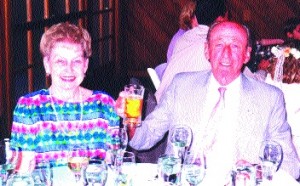

Bankey retired from the USAF at SAC Headquarters, Offutt AFB, Nebraska, in 1968, as a colonel, and now resides in Woodland Hills, Calif., with “Ginny,” his “one and only for the past 62 years.” They have two sons, two daughters, eight grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.