By Captain Bernard L. Brookes

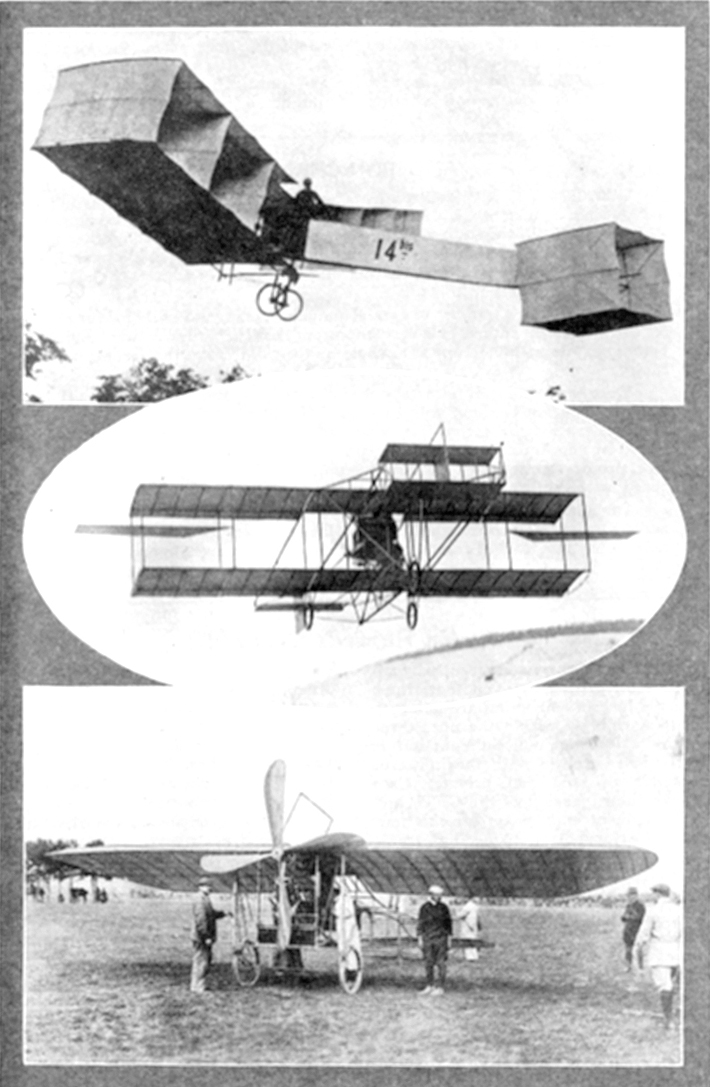

Top: Miracle of Flight! The Santos Dumont biplane (box kite) of 1906. Center: This Curtiss biplane of 1909 won the First Gordon Bennett International Race at a speed of 48 miles per hour! Bottom: A rare photograph of the Bleriot monoplane (1909).

It takes a backward look now and then to chart the long route aviation has come as a measure of the distance yet to be spanned. We approach the 37th anniversary of the first flight at Kitty Hawk on Dec. 17, 1903, with every evidence that the conquest of the air is complete.

Huge Stratoliners climbing seven miles above the storms; dinner in New York, breakfast in Los Angeles; three days to the farthest airport in South America; 24 hours by Clipper plane to Europe; hundreds of little Cubs darting from field to field; pilots braving all weather to see that the mail goes through.

In these things, America has outdistanced the world. But aviation never stands still. Our present race to gain military supremacy in the air gives daily proof of the continuing advance of aviation, as new planes become obsolete almost before the blueprints are dry.

With a backward look we see that the point we have reached is not a goal, but merely the 37th milestone with thousands ahead.

Off the ground

When we see pictures of the queer contrivances in which men first flew, the “miracle of flight” seems even more miraculous. On that first day, the Wright brothers got their ship up a few feet off the ground at 20 miles per hour for only 12 seconds. And even then, it was years before the newspapers would believe that the Wrights had really flown, as it had been the desire in men’s minds to do for so many centuries.

In the seventeenth century, a French tight-wire walker attempted flight with artificial wings. In 1678, Besnier, another Frenchman, built a pair of oscillating wings with which he could leap from elevated positions. At about the same time, Boreilli constructed wings that for years were used as the basis for experimentation.

In 1809, Sir George Cayley in England experimented with gliders. A stream engine driving two aerial screws mounted on a machine supported by a single surface was used by Henson of England in 1842. Twenty-five years later another Englishmen, Wenham, built a model multiplane using several superimposed supporting surfaces. His associate, Stringfellow, added aerial screws.

Other experimenters of the early days were Prof. S.P. Langley, who almost made the grade; Sir Hiram Maxim of England; Ader of France: Otto Lilienthal of Germany; Chanute of our own country, and many another.

After the first flight of the Wright brothers, a number of those who had been experimenting at the same time made progress that cannot be forgotten. Between 1903 and 1910, “Doc” Henry Walden experimented with a series of monoplanes. He was a dentist with a hobby for flying, dentistry keeping him going and flying experiments keeping him broke. Before Walden’s work, the double-wing models had held all attention. In 1909, he built the first successful American monoplane. About the same time, Bleriot perfected a French monoplane.

Early records

Other distinguished names were beginning to emerge, notable among them, that of Glenn Curtiss. His business was running a bicycle shop. Curtiss’ model was a biplane, which in 1906, he equipped with a single high-speed propeller and movable wing tips at the end of the supporting planes. In this machine he won the Gordon Bennett international prize at Rheims, France, flying 12.42 miles in 15 minutes and 56 1/2 seconds.

Later, in 1910, when cross-country flying was getting under way, Curtiss flew from Albany to Governor’s Island, N.Y., a distance of 142 miles, averaging 49 miles per hour and stopping three times for oil and fuel.

A little later, Hamilton, flying a Curtiss biplane, flew from Governor’s Island to Philadelphia and back in an hour and 45 minutes. Farman in Paris won $10,000 for a flight of 118 miles in three hours. Paulhan won the Daily Mail prize for a flight from Paris to London. Bleriot and Moisant crossed the English Channel, flying from Paris to London. Chavez reached an altitude of 1794 meters and later flew across the Swiss Alps. Legagneaux came next with an altitude record of 3100 meters.

Sopwith won the British Michelin Cup with a flight of 100 miles and Cody passed his record with a flight of 185 miles in 4 hours and 47 minutes. Tabetau won the International Cup doing a flight of 361 miles in 7 hours and 48 minutes, and Captain Bellenger of France followed with a flight of 428 miles in 5 hours and 10 minutes. Fourney established a new duration record, covering 447 miles in 11 hours.

The first practical hydroplane flight was made March 2, 1910, by Fabre on the Seine in France, three floats being attached to his monoplane. Glenn Curtiss was experimenting in San Diego at the same time with floats attached to his biplane. In 1911, he received the Aero Club of America trophy for the development of the hydroplane and in 1912, the same club trophy for the Curtiss flying boat.

Pilots and barnstormers

Inventors would have been helpless without that daring lot of test pilots and barnstormers, many of whom gave their lives to the progress of aviation. Ralph Johnston was killed on Nov. 17, 1910. Six weeks later, on Dec. 31, 1910, John Moisant and Arch Hoxey were killed. Others who cracked up and who never will be forgotten were Lincoln Beachey, Lawrence Sperry, Tod Shriver, Tony Badger, Howard Gill and Miss Quimby. Old-timers whose good fortune and the good fortune of the industry have permitted to survive include Bud Mars, Bert Acosta, Harry Atwood, Glenn Martin and Dr. Henry Walden.

The first monoplane accident causing death occurred in Europe on Jan. 4, 1911. M. Leon Delagrange, one of the leading aviators of Europe, while testing his monoplane at a height of 65 feet on the outskirts of Bordeaux, France, was thrown to earth and crushed to death.

Pleasanter dates to remember

But here are other date lines which make better reading.

Charleston, S.C., Jan. 6, 1911: Jimmy Ward, aged 18, thrills thousands of spectators and troops at Fort Moultrie and gains a prize of $5,000. He rose to 5300 feet, the highest point attained in a small 24-hp Curtiss.

San Francisco, Calif., Jan. 15, 1911: History in aviation in this country is made when a real bomb was dropped from the aeroplane on Camp Selfridge Field and exploded. Lt. M.P. Crissey of the Coast Artillery made the experiment. Flying with Philip Parmalee in a Wright biplane at a height of 475 feet, Lieutenant Crissey released a shrapnel shell. On the same day, Lt. John C. Walker of the 8th Infantry was carried aloft to take what was believed to be the first aerial photograph and make observations from a height of 1,000 feet.

San Diego, Calif., Jan 26, 1911: For the first time in the history of aviation, Glenn Curtiss took off from water in his biplane specially equipped with appliances to float the machine and allow it to attain sufficient speed on the surface of the water before lifting. This was the first hydroplane tested and inspected by the Army and Navy. Lt. John C. Walker Jr., of the Army, and Lt. T.G. Ellison of the Navy received instruction at North Island.

Steps toward progress

Feb. 2, 1911: The first Army Appropriation Bill for Aviation was for $25,000. Brig. Gen. James Allen, chief signal officer, said before the Military Affairs Committee, “It is my intention to advertise for bids for 12 aeroplanes for the Signal Corps and establish a number of Aerodromes or hangars—one, of course, to be near Washington, probably at College Park, Md.”

February 7, 1911: The first Airscout. Under orders from the United States War Department, Lt. Benjamin Foulois is to patrol the Mexican border in the vicinity of Juarez. He will be assisted by A.L. Welsh, Wright expert operator. This was the first military aviation patrol. Foulois is now a retired brigadier general.

The first Army message to be delivered by aeroplane was taken by Harry S. Harkness from Major McManus, commander of Fort Rosecrans, Calif., to Lieutenant Ruhlin in charge of the border patrol. He covered 45 miles in 56 minutes.

May 4, 1911: The first Air Meet. Lincoln Beachey circles the Capital Dome from Benning track. Others at the meet were J.A.D. McCurdy, Glenn H. Curtiss.

First orders

May 14, 1911: Order No. 1: The War Department announces arrangements are being made to build four hangars at College Park, Md., for the accommodation of the four aeroplanes, which will be operated over the aviation field at that place this summer. Bids for construction will be opened by the Department Quartermaster in this city on May 20.

A class of Army officers will be given instructionary training in aviation. Some of these officers have been designated. Others will be assigned later.

June 12, 1911: Order No. 2: Brig. Gen. James Allen, chief signal officer of the Army, expects that the operation of aeroplanes over College Park, Md., the Army aeronautic field, will commence on or about June 15. The U.S. Army has purchased a Wright, a Curtiss and a Burgess. The fourth has not yet been selected. Capt. Charles deForest Chandler, one of the aeronautic experts of the Signal Corps, who has been on duty at Fort Omaha, Neb., will be in charge of the class of young officers who will be given instruction at College Park, Md.

The class will include at least eight officers—two for each machine. Second Lt. Thomas DeW. Milling, 15th Cavalry, and Henry H. Arnold, 29th Infantry, who have been given instructions in aero flights and in aeroplane construction and shop work at the Wright factory, Dayton, Ohio. Lt. Benjamin Foulois and First Lt. Paul W. Beck of the 18th Infantry are among those ordered to College Park.

First Lt. Roy C. Kirtland, 14th Infantry, is already on duty. A detachment of 12 enlisted men of the Signal Corps is also on duty. (The author, Captain Brookes was one of the 12.) Other officers assigned are Lts. Rockwell and Spike Hennessy.

June 28, 1911: Lt. H.H. Arnold—now chief of the Army Air Corps—makes a 1,500-foot flight. Lt. Milling gives instruction to Lt. Kirtland and Captain Chandler. Brig. Gen. Allen is greatly pleased and says, “I hope to have one machine at every Army post.”

World War I planes

In 1914, World War I took over aviation. Speed records, stunt flying, guns fired from airplanes demonstrated in advance that here was another swift weapon of death.

Germany was the earliest developer of large planes carrying heavy guns. Other nations had regarded the airplane as merely a means of observation, but no equipment was provided for immediately conveying information. Even so, anti-aircraft batteries were devised and this in turn necessitated that planes be armed both for offense and defense.

Several types were brought out—the Curtiss “JN” army trainer using Curtiss 90-hp engines; the Glenn Martin Bomber with twin 400-hp Liberty engine; the de Havilland “4” with 400-hp engine. The French were using the Nieuport 28 with 9 cylinder 140-hp Gnome engine; the British, the Handley Page Bomber with twin Rolls-Royce 250-hp engine; and the Italians, the Caproni three-engined bomber.

Speed increased to 130 miles per hour and flying heights to over 20,000 feet. Bombing attacks went on day and night. Besides service to the Army for observation and fighting, the airplane became “the eyes” of the Navy in defense against submarines. The airplane had become the deadliest engine of war.

Those first World War planes were not armored. Pilots were completely without protection from gunfire. The jobs we flew in that war compared with the Flying Fortresses and lightning-swift modern pursuit planes in about the same ratio as the Kitty Hawk would compare with a Stratoliner.

The Mitchell plan

The late General Mitchell, as chief of the Air Service with the A.E.F., made his first recommendations to Washington on May 17, 1917. He estimated that America needed 5,000 planes at the front, 5,000 in reserve, and 10,000 to replace them in every four months of combat. The war was over before much progress was made. Only now—23 years later—is Billy Mitchell’s far-sighted program being executed.

Air mail starts

In 1918, the big impetus to commercial flying came. Otto Prager, a Texas newspaper man, appointed by Postmaster General Burleson as assistant postmaster general, conceived the idea of air mail, and long tried to get it over. The first try was a disheartening failure.

But failure was a word that neither Prager nor willing pilots knew. On May 31, 1919, a regular air mail schedule was established between Washington and New York.

The rest is history.

Like all other early aviation attempts, it required matchless heroism. More than one crack pilot gave up his life to make today’s air mail as sure as the sunrise and to set regular schedules for the passenger service that was to follow.

These are names and milestones that have made aviation great and which in retrospect give a measure of the distance that, with undiminished speed, aviation has yet to go.