By Stuart Leuthner

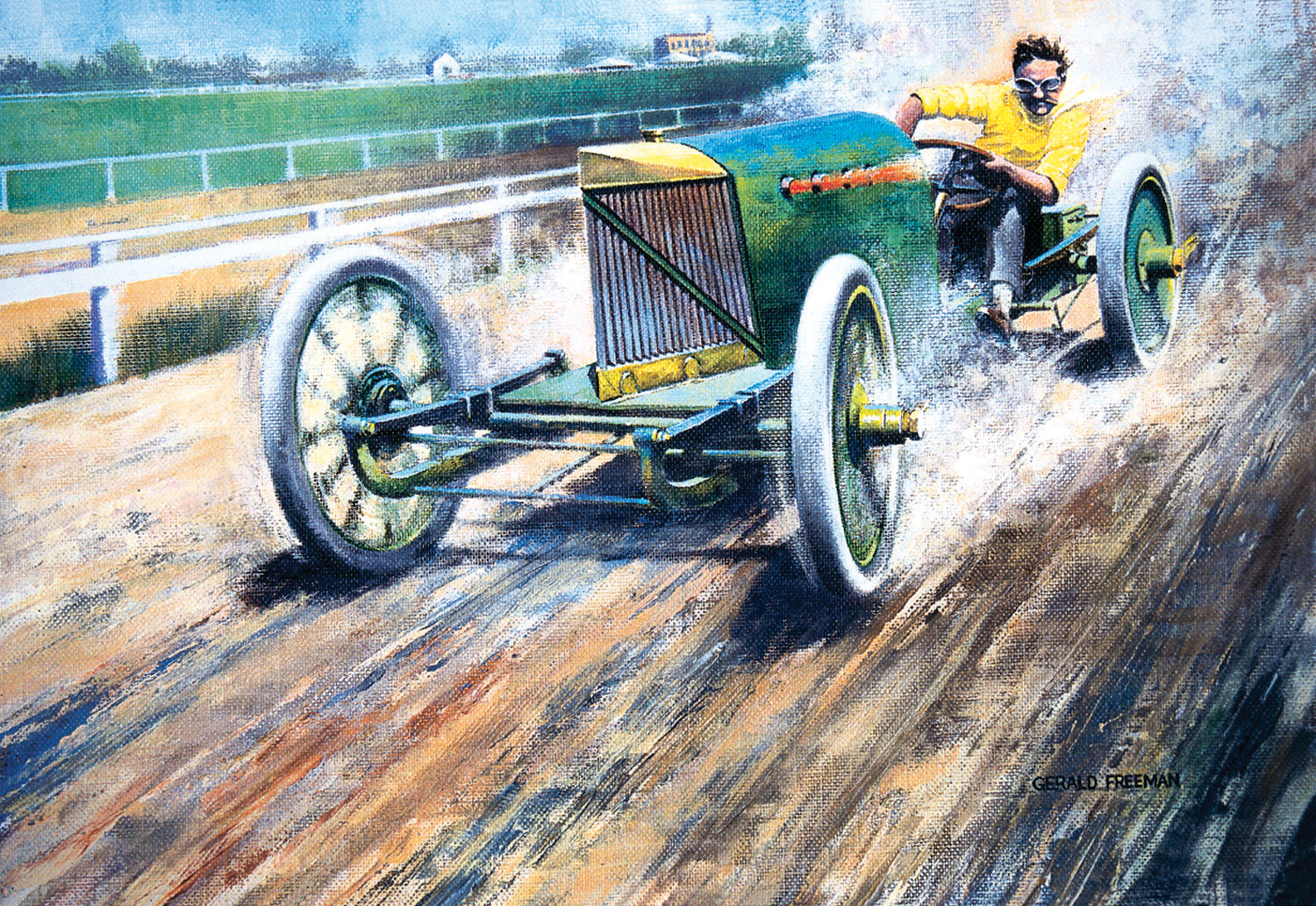

The daredevil driver tests the Peerless Green Dragon. Barney Oldfield’s style of skidding through the turns under full throttle thrilled spectators and unnerved his fellow drivers.

Barney Oldfield met Henry Ford for the first time during the summer of 1902. Although the two men couldn’t have been more different, their relationship would result in one man creating an automobile empire and the other becoming known as the “Master Driver of the World.”

Ford, like other pioneer auto makers, realized that victories on the race track translated into sales in the showroom—race on Sunday, sell on Monday. Early in his career, Ford wrote a letter to his brother in which he stated, “My company will kick about me following racing but they will get the advertising and I expect to make $ where I can’t make ¢ at manufacturing.”

During 1901, Ford built a race car he called No. 999, named after a New York Central locomotive that pulled the Empire State Express at 112 mph in 1893. Ford’s machine was no beauty; in fact, one writer described it as “a brute.” No. 999 was powered by a four-cylinder engine that developed somewhere between 70 and 80 horsepower. The engine was unique in that it was mounted in the front of the car instead of under the seat, where most early engines were located.

No. 999 was nine feet, nine inches long, had one forward speed, no springs or shock absorbers and was fitted with one seat. Describing the car, Ford said, “…the roar of those cylinders alone was enough to half kill a man. There was only one seat. One life to a car is enough.”

Ford drove the car himself on several occasions (he set the world’s speed record of 91 mph on a frozen lake in 1904) but wisely decided his skills were better used building cars rather than racing them. One of Ford’s early associates, an ex-bicycle racer named Tom Cooper, suggested that Ford should hire his friend and fellow bicycle racer, Barney Oldfield, to drive the car. “Nothing’s too fast for him,” Cooper told Ford. “He’ll try anything once.”

Berna Eli Oldfield was born Jan. 29, 1878, in Wauseon, Ohio. He spent his early childhood on the family farm and displayed his flair for showmanship orchestrating a circus act with a neighbor’s trained pig and an old horse.

Times were hard and the Oldfields left the farm and moved to Toledo. Berna’s father, Henry, managed to find a job in the state hospital for the insane and his wife, Sarah, worked as a milliner and ran a boarding house.

Berna Oldfield did anything he could to make a few bucks. He sold newspapers, carried water for railroad labor gangs, cleared tables at the hospital his father worked at, bused tables and ran the elevator in a downtown hotel. He picked up his nickname when one of the residents at the hotel began to call him “Barney.”

Oldfield managed to save up enough to buy a bicycle and by the time he was 17, he was an accomplished bicycle racer, riding professionally for the Stearns Bicycle Company. The League of American Wheelmen were appalled that “paid amateurs” were involved with bicycle racing. Threatened with being blacklisted, Oldfield outfoxed the league by forming his own team, Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles.

Bicycle racing in the early 1900s was extremely popular, but it was not a sport for the timid. Speeds were closing in on 40 miles per hour and racers would often kick another rider in the shins or, if that didn’t work, simply force them off the road. In self defense, Oldfield soon developed his trademark hard-charging style that would serve him so well in the future.

At one point, Oldfield put away his bicycle and stepped into the boxing ring, a sport that promised a bigger paycheck. Billed as the “Toledo Terror,” his career as a pugilist was cut short by an attack of typhoid fever and he returned to bike racing.

Oldfield was living in Salt Lake City when Cooper called and asked him if he would like to drive No. 999. He had been married and separated, the bicycle craze was beginning to fade and Oldfield was scratching for what little money he could racing motorcycles. With nothing to lose, Oldfield immediately bought a train ticket and headed for Groose Pointe.

When he saw No. 999 for the first time, Oldfield admitted to Ford and Cooper, “I’ve never driven a car!” The automaker realized this could be a problem, so Oldfield spent the next week learning how to drive. Ed “Spider” Huff, a Ford employee who had helped build the race car, would crouch behind Oldfield as they careened around the track, shouting out advice. When Huff told Oldfield that Ford was concerned for his driver’s safety, Oldfield shrugged and told Huff, “I may as well be dead as dead broke.”

On Oct. 25, 1902, under threatening skies at the Groose Pointe horse track, Oldfield, driving in his first race, not only soundly defeated the field, including Alexander Winton in his Bullet, but also set a new American speed record. On Memorial Day in 1903, at the Empire City Track (now Yonkers Raceway), Oldfield drove a mile in a minute flat and two months later, covered a mile in 0:55.8.

Oldfield used the same techniques in race cars that made him a winner on bicycles. He would swing wide in the turns, sometimes actually scraping the rail. This not only allowed him to maintain his speed, but also tended to intimidate other drivers. Oldfield also perfected the rolling start. He would lurk behind the other cars, and then, stomping on the throttle, time it so he hit the starting line at full acceleration, just as the flag dropped.

The Automobile magazine described Oldfield’s performance at the Empire City Track: “The rear wheels slide sideways for a distance of 50 feet, throwing up a huge cloud of dirt. Men were white-faced and breathless, while women covered their eyes and sank back, overcome by the recklessness of it all.”

After watching Oldfield continue to leave the competition in his dust, Winton offered him a deal he couldn’t resist—a salary, an expense account and free cars. But Oldfield’s relationship with Winton was short lived. Although his performance on the track was never questioned, Oldfield liked to gamble, brawl and make uncouth pronouncements.

Later in his career, Firestone hired him to promote a line of Oldfield tires, but Harvey Firestone, upset by the driver’s bad-boy reputation, ended up canceling the deal. In 1904, Oldfield was hired to race the Peerless Green Dragon. During the early 20th century, Peerless automobiles were among the finest cars built. The vehicles featured a host of innovative features including a driveshaft with floating rear axle, a stamped steel frame, a tilting steering wheel, the use of aluminum to save weight and the first enclosed body.

The original Green Dragon was powered by two 40-horsepower engines joined together. The square hood was painted green and short exhaust pipes belched fire—hence the name Green Dragon.

Oldfield scored his first victory in the Green Dragon during August 1904, beating Herb Lytles in his Pope Torpedo on a track in Buffalo, N.Y. That same month, he competed in the Louisiana Purchase Trophy Race at the St. Louis World’s Fair. Wearing a jaunty green driving suit and helmet, Oldfield was closing in on the leader when his goggles were shattered by a rock. Blinded by the dust, he hurtled off the track. Two spectators were killed, and 12 were injured. Oldfield was also severely injured and the Green Dragon was destroyed.

Peerless built a second Green Dragon, but opted for a single, straight-eight engine that produced 90 horsepower. Oldfield, now healed, drove the car to a series of dramatic victories on the nation’s tracks during 1904. On December 17, he established a new record, covering a mile in 54 seconds at Agricultural Park (the present Exposition Park) in Los Angeles.

The Los Angeles Herald gushed, “When Barney came onto the track in the famous Green Dragon, the hearty reception he received proved that the people of the West were with him and appreciated his nerve in driving this death-dealing machine, which tears off the miles at such terrific speed, belching fire and smoke the while and making the air tremble with the explosions from its eight cylinders.”

Oldfield won a few races driving the Green Dragon during 1905, but he was plagued by a series of mishaps. A wheel collapsed during a race in Connecticut and a blown tire in Chicago sent him through a fence. On August 9 in Detroit, Oldfield hooked wheels with the Reo Red Bird and crashed.

In a rather bizarre turn of events, Oldfield and the Green Dragon now headed for Broadway where he and his old friend, Tom Cooper, appeared in the “Vanderbilt Cup,” a play loosely based on the famous races held on Long Island during the early 1900s. Oldfield played a poor mechanic who saves the day, behind the wheel of the patched up Green Dragon, and Cooper, in the Blue Streak, another Peerless race car, would actually recreate a race on the stage. As the revolving, painted scenery flashed by behind them, the two drivers would rev their engines—the cars were sitting on rollers—and appear to be jockeying for the lead. It must have been a memorable experience for theatergoers in the first few rows. Although Oldfield drove a third Green Dragon during the summer of 1906, Peerless made the decision to drop out of racing and Oldfield ended up buying the Green Dragon #3 and the Blue Streak. He hooked up with an extremely shrewd agent, Will Pickens, and was soon traveling from town to town in his private railroad car, challenging anyone who was brave enough to race him.

His most popular performances were a series of races with the daredevil aviator, Lincoln Beachey. Beachey, who began his career flying dirigibles, mastered aerobatic feats that no man had attempted or even dreamed of before. Orville Wright wrote, “An aeroplane in the hands of Lincoln Beachey is poetry.”

The “races” between Oldfield and Beachey weren’t real contests, since the two men were partners, but crowds would be mesmerized as Oldfield, clenching his trademark cigar between his teeth (he had chipped several teeth in an accident and the cigar acted as a cushion) would roar around the track with Beachey in his airplane, a few feet above. On several occasions, Beachey would actually knock Oldfield’s hat off with his landing gear as they sped by the grandstand at 70 miles an hour.

Oldfield was now so popular he would be paid $1,000 to show up for a race and he began to hobnob with the rich and famous. He also starred in several movies, including a 1913 Mack Sennett silent film, “Barney Oldfield’s Race for a Life.” In the film’s dramatic climax, Oldfield races a train to save heroine Mable Normand, who has been tied to the tracks by the black-hatted villain played by Ford Sterling.

He co-starred with Patsy Ruth Miller and a young William Demarest in “The First Auto,” a comedy contrasting the horse-reliant oldsters of the turn of the century and the auto-mad youth of the Roaring ’20s.

On Oct. 10, 1914, Oldfield drove a Stutz to victory in the “Cactus Derby,” a race from Los Angeles to Phoenix. Oldfield later described the 673-mile race “along canyons and precipices full of treacherous turns” as “my toughest race.”

To commemorate his success in that event, Oldfield was awarded a medal that included an inscription, “The Possessor of the medal has won the Los Angeles to Phoenix Road Race, thereby proving himself to be the Master Driver of the World.”

Barney Oldfield and the second Green Dragon dominated the nation’s race tracks during 1904. On December 17, he covered a mile in a record-breaking 54 seconds.

Oldfield went on to set more records driving a variety of cars including the “Blitzen Benz,” a Maxwell, a Fiat, a National named Old Glory and the famous Golden Submarine. Built in 1917 by Harry A. Miller, the streamlined car’s enclosed cockpit was an attempt by Oldfield to improve safety after his friend and fellow racer, Bob Burman, was killed.

Racing was very good to Barney Oldfield and he enjoyed both the fame and fortune it brought him. He often wore thousands of dollars’ worth of jewelry, including a four-carat diamond pinky ring. He was extremely generous to friends and fans and was known to be an extravagant tipper.

The endless traveling and his constant drinking put a strain on Oldfield’s family life and he was married four times. Bess Holland Oldfield, who married him twice, sent her husband a telegram after he won a race that admonished him to “Please save booze party until you get home.”

On more than one occasion, his popularity, rowdy behavior and bending of the rules resulted in Oldfield’s being suspended by racing’s sanctioning body of the day, the American Automobile Association. The wealthy overseers of automobile racing, determined to maintain the sport as their exclusive enclave, often excluded Oldfield from events for trivial transgressions. Because of this, Oldfield never competed in many of automobile racing’s most important events, including the Vanderbilt Cup and the Gordon-Bennett Trophy.

Much to the chagrin of racing’s elite, however, Oldfield’s “outlaw” reputation only added to his fame and popularity with the public. Always the showman, Oldfield would sometimes play with another driver, holding his car back, only to step on it during the final lap and cross the finish line first, waving at the cheering crowd. He would then bellow out, “You know me, Barney Oldfield,” a tag line that became so famous he used it to sign his personal correspondence.

Barney Oldfield officially retired from racing in 1918, but on occasion would still climb behind the wheel. In 1927, he averaged 76.4 mph in a 1,000-mile nonstop stock car event at Culver City in California. Oldfield was living in Beverly Hills when he died in 1946.

During the 1930s, Henry Ford visited Oldfield at his home in California. During their conversation, Ford told his former driver, “Barney, I made you and you made me.” Oldfield shook his head and said, “No, Henry, old No. 999 made us both.”