By Deb Smith

Steven J. Hill says it’s nearly impossible to get the “farming gene” out of your blood, especially if you’ve come from a long line of Michigan farmers—five generations to be exact. But he tried. The youngest of two sons born to the fourth generation of Hills in Saginaw, Mich., he spent his childhood among the rich, fertile farmland, located near the state’s “thumb,” as the locals like to say.

This farm had been the only means of livelihood of the generations prior to my father,” explained Hill.

However, his father, William Hill, didn’t farm. By the time the farm was passed to him, the economy, among other things, made it necessary for the elder Hill to seek employment outside the home.

“My dad always had some kind of a 40-hour-a-week job,” Hill said.

Interestingly, the same fate would fall onto Hill and his brother and father’s namesake, William Hill IV.

“I was probably 13 and my brother was 15, when my dad said, ‘Son, the farm, and all of its working, are up to you and your brother,” Hill recalled.

Sadly enough, he said the most money the family ever made on the farm was the money the government gave them in agreement to not grow crops in order to keep the price of certain commodities high. Therefore, Hill began to look for his future in other directions. He eventually looked up.

It was the late sixties, and the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union was in full swing. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and American Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon all agreed that mastering the art of space travel was crucial to demonstrate scientific superiority.

Although Hill knew he was interested in engineering, and had applied to several colleges, he still wasn’t exactly sure which type of engineering he would study until July 20, 1969.

“I wasn’t always interested in aviation, especially having grown up in rural Michigan,” he said. “But what always did interest me and got me going in that direction was the space program—watching the television, and the repeated broadcasts of when we finally did make it to the moon. That event, more than anything else, told me that if I went down an engineering career, I wanted to work in aerospace.”

Hill said the moment was quite serendipitous, as his parents were beginning to ask him to start making decision about what he wanted to do with his life. In August 1969, Hill left his rural abode for the University of Colorado at Boulder. He would spend the next five years completing a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering.

To get to the university, the 17 year old would need to fly. That was something he’d never done before. He admits the plane ride in itself was memorable, but there were factors other than Bernoulli’s principle going on that made this particular flight stick in his head.

“I had this whole rebellion thing going on,” confessed Hill.

He said that even though his relationship with his parents was great, it was time to break away from home and the farm.

“I knew I wasn’t going to be a farmer,” he explained.

Anxious to be on his own, he said goodbye to his parents at the airport parking lot and headed into the terminal. The first thing he did once inside was buy a pack of cigarettes, signifying that he was now a “free man.”

“I had very strict parents, so smoking was never permitted whatsoever,” said Hill.

When a smiling ticket agent at the check-in counter asked, “Smoking or non-smoking?” he quickly responded, “Smoking.” Then, he made his way to the gate. He recalls sitting in the back of the United Airlines Boeing 727 with all the smokers.

“As soon as the smoking light came on, the blue haze started to appear,” he said. “It became so thick I couldn’t see the front of the plane from back there.”

Seated in the next to the last row, Hill lit up—and instantly began coughing.

“Other than a couple of drags with some friends under the bleachers at a football game in high school, I never had really smoked at all,” he said.

As he gasped for air, red-faced, a concerned gentleman next to him leaned toward him and said, “Smoke much, son?”

The BBJ is a high-performance derivative of the Next-Generation 737-700. Designed for corporate and VIP applications, the aircraft combines the size of the 737-700 fuselage (110 feet, 4 inches)with the strengthened wings and landing gear from the 737-800

The man’s question was eerily similar to something his dad might have said.

“I suffered through the rest of the flight,” said Hill. “I gave that pack of cigarettes to the man before I left.”

With his memorable first flight behind him, Hill began his studies with great enthusiasm. He even began taking flying lessons.

“My flying all took place in college in a Mooney,” explained Hill. “It was owned by a professor in the aerospace engineering department. He had a great philosophy; he wanted his students to have the experience of flying, so if we bought the gas, we could go on any weekend with Professor Kennedy and fly with him.”

Hill even accompanied his professor on a cross-country trip to St. Louis to present a paper during his junior year. However, he wasn’t able to continue his flight training. He opted to prioritize his studies over flying.

“Basically, I went deeply into debt to finish my degree,” said Hill. “I owed a lot to my parents and to others, and really couldn’t afford to finish the lessons.”

In 1973, Hill earned a bachelor’s degree. Just 12 months later, he earned a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering. Now it was time to find a job.

“When I graduated, I had an offer from Boeing,” said Hill. “But I also had a number of other offers as well.”

One of those other offers was from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. What really helped Hill make up his mind was something more than money.

“I actually spent a week back in Boston at MIT, trying to feel comfortable in a major city,” he said. “The Pacific Northwest is really a beautiful area; it was more me—more like the country side of me. You have the mountains and the sea, and Boston is just a major metropolitan area. I personally didn’t feel comfortable there.”

Although MIT had offered Hill more money, he chose to start his career with The Boeing Company.

“I really went with my heart on this one,” he said.

He began his career with Boeing in 1974 as an aeronautical engineer for the Boeing Defense Group. In that position, he worked on airborne warning and control system stability and control flight testing, U.S. Air Force flight simulator acceptance programs, and flow field analysis for advanced cruise missiles.

From 1980 to 1988, he served as a manager in Boeing’s flight operations division. There, his organization provided vital technical flight operations assistance, training, and manuals in support of all of Boeing’s commercial models. For the next decade, Boeing placed Hill in Europe as its director of sales for Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

In July 1996, Boeing announced a joint venture with General Electric called Boeing Business Jets.

“It started out between a former Boeing CEO, Phil Condit, and Jack Welch, CEO of GE,” explained Hill.

Hill explained that since each had a company that had VIP airplanes of a smaller nature, they both did a lot of business flying.

“We saw an opportunity to do it better,” Hill said. “We saw that we had a product in the 737 and that we could build a high-quality, spacious, long-range VIP airplane that would let us capture a good share of the market.”

Boeing Business Jets was established as a marketing arrangement in the form of a contract venture. Boeing manages the day-to-day operations, manufactures the planes, and is responsible for sales and marketing activities, with support from GE. GE provides the airplane’s engines. Both companies are involved in customer support and decisions affecting pricing and market applications.

The first Boeing Business Jet rolled out of Boeing’s Renton, Wash. factory on July 26, 1998, and received FAA and JAA certification on Oct. 29, 1998. The BBJ is a high-performance derivative of the Next-Generation 737-700. Designed for corporate and VIP applications, the aircraft combines the size of the 737-700 fuselage (110 feet, 4 inches) with the strengthened wings and landing gear from the larger and heavier 737-800. The tailored combination provides owners with a business jet platform having maximum range capability (6,200 miles) while requiring less than 6,000 feet of runway.

The BBJ cruises at speeds of up to .82 Mach (541 miles per hour) and serves such routes as Los Angeles to London or Paris; New York to Buenos Aires, Argentine; and London to Johannesburg, South Africa.

The BBJ cruises at speeds of up to .82 Mach (541 miles per hour) and serves such routes as Los Angeles to London or Paris; New York to Buenos Aires, Argentine; and London to Johannesburg, South Africa. The same CFM56-7 engines used on the Next-Generation 737 power the BBJ. CFM International, a 50/50 joint company between Snecma Moteurs of France and GE, produces the engines.

In 1998, Hill returned from Europe to join Boeing Business Jets as vice president of operations. By 2002, he would be deputy vice president of Boeing Aircraft Trading. He was named president of BBJ in August 2004, replacing Lee Monson.

Hill proudly said that this year Boeing Business Jets will hit the 100-plane mark.

“We’ve really been quite successful selling this concept, although we don’t have a huge number of large corporations using them,” he said. “It’s a big thing for a company like us, especially for the short amount of time we’ve been around.”

He adds that 100 is a “good clean number.”

“We try to be extremely clean in the fact that we’ve sold 95 firm sales,” said Hill, referring to the fact that often industry numbers can mix and match commercial and private aircraft sales, especially in the VIP market. “These are BBJs that have been sold only into private aviation.”

According to Hill, what has really helped the BBJ become successful is not only the private individual market, but also its ability to answer the very unique needs of heads of state.

“It makes a great mini Air Force One for smaller countries,” said Hill.

As for changing the marketplace, Hill said BBJ has done more than just deliver the right product to market.

“The whole concept of Boeing Business Jets was to not just put the right airplane together, but rather to put together the right company behind it,” he said.

While outsiders may think BBJ looks like a sales and marketing corporation inside of parent organization Boeing Commercial Airplanes, Hill said BBJ is actually a small VIP manufacturing and support organization for VIP clientele.

“What they care about is the fact there is a one-stop shop for them, that there’s somebody who cares for them, and there’s somebody to support their airplane after the sale,” he said. “We have developed unique programs that aren’t only competitive, but also satisfy the needs of the customers.”

BBJ has its own series of dedicated field representatives that focus only on VIP clientele and airplanes, Hill said.

“We have our own spares exchange program, and our own training program as well,” Hill said. “We treat the training side of the program much differently than our commercial side. It’s just part of a personal care kind of approach we use at BBJ. We also have our own warranty program, and it’s all handled in a one-stop shop.”

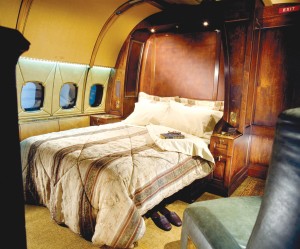

What makes the BBJ unique is the fact that it arrives from Boeing to the customer in a “green” configuration (no paint or interior). Then, arrangements are made to install a long-range auxiliary fuel system at PATS Aircraft, LLC, the Delaware facility of DeCrane Aircraft Systems Integration Group.

Next, the BBJ is sent to a completion center of the customer’s selection for interior completion. Currently there are five BBJ completion centers in the world, two in Europe and three in the United States.

Because the BBJ is both a business and lifestyle necessity, BBJ has now started aligning itself with many of the best-known yacht shows.

“The reason we’ve done this is that we’re both seeking the same clientele—the private, high-net-worth individual that’s looking at super yachts,” said Hill. “Because of their yacht getting bigger, their airplane needs to be bigger, too.”

As for the future, Hill has an optimistic outlook.

“Over the next five years, you’re going to see Boeing responding to a varied customer base with the right product, and continue to see us developing new technologies that enhance the comfort and productivity of owners and operators,” he said.

One of those developments is certainly the lower cabin altitude modification, which will be available soon for retrofit and standard on all BBJs in 2006. Hill said the new innovation will bring the inside cabin pressure down from about 8,000 feet MSL to about 6,500 feet MSL. That will result in a more normal and pleasant ride, particularly on longer trips.

Hill added that Boeing’s new Future Air Navigation System will make its way into a more prevalent place in the market. FANS is a system that streamlines communications between airplane crews and air traffic controllers. It provides controllers with real-time airplane position reports and clearance requests for in-flight changes. The crew receives the response via nearly instantaneous text messages displayed on flight-deck computer screens.

Using Oceanic Air Traffic control satellites and VHF radio data link networks, FANS reduces conversations between flight crews and controllers, reducing congested radio frequencies. Hill assures customers that even more innovations are coming in the future, but what’s important is the fact the BBJ has raised the standards for the VIP market.

The BBJ offers executives and VIPs not only the ultimate in range, space and flexibility, but also in comfort.

He said that before, the largest purpose-built VIP plane was the Gulfstream. What they’ve done is given people an option to step up.

“There wasn’t a step up before, unless you went thought an ex-commercial airline, or bought a used jet—or even a new one from Boeing,” he said. “Until BBJ, you were totally on your own to have it outfitted and have any type of support.”

Steve Hill’s dreams of touching the aerospace industry have come full circle. As far as that “farming gene,” it’s been more than 35 years since he left the 40-acre rural fields of Saginaw. His brother left, too, and in 1971, Hill’s father sold the family farm and settled in Colorado. Hill tried to get farming out his system, but hasn’t managed to do so yet.

“Oddly enough, farming never leaves your blood,” reflected Hill.

His brother would agree. Today, he owns a farm, which Hill says is actually “more like an apple orchard.” And Hill?

“About 22 years ago, I bought a 10-acre horse farm in the south part of Seattle,” he said.

The best of both worlds for Hill? Of course.

For more information on Boeing Business Jets, visit [http://www.boeing.com/commercial/bbj].