By Greg Brown

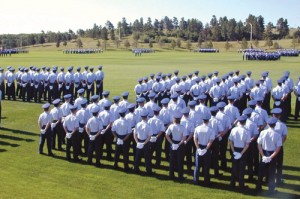

Sweat drenched our collars as we chased blue-suited cadets across the parade ground.

“Imagine how hot they must feel, marching in those uniforms,” huffed Jean. “At least we get to wear shorts. Can you see Austin?”

“No,” I replied. “I’ve lost sight of him.”

Warm memories of that sweltering Colorado day would reawaken years later, when Erik Primosch returned from Honduras. Erik has been best friends with our son, Austin, since moving to our neighborhood at age 8. Together they navigated the adventures and traumas of youth—games and sleepovers, girls, arguments and homework parties.

The two pals could hardly be more different. Austin is slight with brown hair and grey-blue eyes, while Erik is tall, blonde and muscular. Erik starred on the state championship baseball team, while Austin earned his pilot’s license and lettered in cross-country and track. One sport they did share was tennis; on-court rivalry consumed many a Saturday morning.

But boyhood can’t last forever, and for these two, the separation was drastic. Shortly after high school graduation, Austin departed for the Air Force Academy to pursue his dream of flight; two months later, Erik headed for a religious mission in Central America. I thought I’d be the one crying when we dropped Austin at the airport, but instead it was 6’3″ Erik who burst into tears while hugging his buddy goodbye. Fueled by years of father-son flying adventures, my own turmoil gnawed silently from within.

During that first summer of “beast”—basic cadet training—Austin was allowed to communicate through letters only. We’d heard from an older cadet, Adam Keith, that mail call was the bright spot in a basic cadet’s rigorous day, so Jean and I wrote often.

“Remember, address my mail as ‘Basic Cadet,’ or I’ll get in trouble,” Austin had warned us. “And Mom—no perfume or pink envelopes!”

In place of Austin’s voice, we now learned to treasure his letters. In them, he shared tales of hardship and humor: about the physical challenges, the aptitude tests, the camaraderie and the emotional pressures.

“I never thought I’d say this, Dad, but I’m sure glad Mom taught me to iron,” he wrote one day. “The other guys will do anything for me to press their uniforms.”

Like all cadet parents, Jean and I eagerly awaited “Doolie Day Out,” the appointed day for Austin’s first phone call. Finally it came.

“I’ve completed ‘first beast!'” he boasted. “But the hardest part is yet to come. Tomorrow we march to Jack’s Valley to begin military training and the obstacle courses.”

“We believe in you, Austin!” proclaimed Jean.

She proceeded with motherly questions about health and clean clothes until Austin interrupted, “Sorry Mom, but I have only a few minutes left to call Erik. Gotta go. See you on Parents Weekend!”

That eagerly anticipated event beckoned from faraway September, but Erik was departing mid-August.

“If only I could see Austin once more before leaving,” said Erik when we later shared notes. Although doubtful, I promised to keep him posted.

Early in August, I heard about something called the “Acceptance Parade” and phoned Adam for information.

“It’s a big deal, celebrating the cadets’ completion of basic training,” he said. “Afterwards they get their shoulder boards and are accepted as full-fledged cadets.”

“Sounds important, Adam!” I said. “Why hasn’t anyone told us about it?”

“It’s really more for the cadets than for outsiders,” he explained.

“Can parents attend?” I asked.

“Yes, but there’s no provision for visitors to meet with cadets,” he said. “You might fly all the way from Phoenix to Colorado Springs and get just five minutes with Austin or worse yet, not see him at all.”

Jean and I didn’t intend to miss this mission, nor did Erik. Within days, we winged northeastward in the Flying Carpet. But how strange it seemed, after so many years flying with Austin, navigating those Colorado mountain passes without him at the controls.

Jean, Erik and I were sharing a hotel room. We pursued that swarm of marching cadets across the Academy parade ground.

“Amazing how similar they all look in uniform,” said Jean. “Was that Austin?”

“I think so!” said Erik.

“Where?” I asked.

We ran to keep up, but lost sight of Austin. Then, to our dismay, we were herded with other parents away from the cadets to the chapel overlook. Now we’d never find him.

Just at that most discouraging moment, Adam Keith showed up.

“I hoped you’d be here,” he said, pumping our hands. “I’ve just pinned on Austin’s shoulder boards. If his squadron gets released from duty, he’ll meet us here. Cross your fingers.”

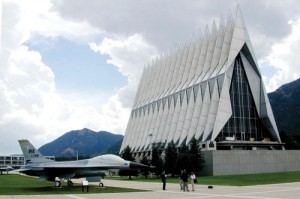

Intently, we scanned amongst soft green mountains and stiletto-nosed fighter planes for a single blue cadet among legions of 4,000. Then we heard it.

“Mom! Dad!” Up the hill rushed a painfully thin young man, resplendent in service hat and uniform. “And Erik! I can’t believe you came, too!”

“You four get out of here, before some upperclassman orders Austin back to the dorms,” said Adam.

“But I can’t leave base!” said Austin.

“Then go to the visitor center,” he ordered. “But get moving!”

Nervously, Austin led us up the wooded trail behind the famed chapel to the visitor center. There, on a shady bench, we relived adventures old and new over warm soda and cold hotdogs.

“First ‘normal’ meal I’ve had in six weeks!” said Austin, excitedly.

“No wonder you’re so thin,” replied his mother.

“How was Jack’s Valley?” asked Erik.

High school buddies Austin and Erik say their goodbyes. They will not see each other again for two and a half years.

“It was tough and so dusty that everyone got a cough called ‘Jack’s Hack,'” said Austin. “But something really cool happened. When we marched to Jack’s Valley, our squadron leader told us to look back at the chapel. ‘Next time you see that chapel, it will mean one of two things,’ he said. ‘Either you couldn’t cut it and are dropping out, or you’ve conquered ‘beast’ and are bound for the Acceptance Parade. For those who make it, that will be the proudest moment of your life.’ Sure enough, I had a lump in my throat when we cleared that hill yesterday and saw the chapel. And here we are at the parade!”

Already it was time for Austin to go. We snapped pictures of the two best friends—one in uniform, the other sporting shorts and a backwards baseball cap—then hugged goodbye and split for the overlook to watch noon formation. There, we met less fortunate parents from across the country, who had missed seeing their own sons and daughters. Silently, we blessed our good fortune.

It was a long flight home that afternoon, dodging summertime thunderstorms over the high country of Colorado and New Mexico. Weather forced a detour south over Santa Fe. But despite bumps, heat, and headwinds, we were at peace. Austin’s spirit flew with Jean and me while Erik slept in the back seat. Now, it was two and a half years later, and Erik and Austin hadn’t seen each other since. With Erik home and Austin’s leave coming up, I was reminded of another basic training letter that likely spoke for them both.

“It’s pretty crazy here,” Austin wrote. “Something wonderful and something terrible happens every day.”

Those guys would have plenty to discuss.

Author of numerous books and articles, Greg Brown is a columnist for AOPA Flight Training magazine. Read more of his tales in “Flying Carpet: The Soul of an Airplane,” available through your favorite bookstore, pilot shop or online catalog or visit [http://www.gregbrownflyingcarpet.com].