By Di Freeze

While Lt. Arthur “Tex” Anders was in China, assigned to Yangtze River patrol, his wife Muriel gave birth to William Alison Anders, on Oct. 17, 1933, in Hong Kong. The family later spent time in Annapolis, Md., where Lt. Anders instructed math at the Naval Postgraduate School, before returning to China. In 1937, when the Japanese attacked Nanking, Muriel and Bill Anders fled.

“We escaped first by a troop train,” recalled Maj. Gen. Bill Anders (USAF Reserve, ret.). “Trains full of young Chinese were going towards the battle. My mother and I and another woman found an empty car in a train heading the other way. I slept on a trunk. Nobody wanted to eat the Chinese food, so we ate Campbell’s noodle soup, boiled in a bucket.”

They eventually arrived at Canton (now Guangzhou).

“While we were in the hotel that night, the lights went out,” he said. “A Chinese porter with a candle scrambled us down a fire escape. The hotel served bullion tea on the porch to my mother while the Japanese came right overhead and dropped their bombs on the ships in the Pearl River, about 200 yards away. I thought, ‘Wow! Look at that.'”

Anders returned to that very building decades later.

“My son and I visited that hotel and found the same stairwell,” he recalled. “A bunch of apartments now block the view of the river.”

His awe of the aircraft that day didn’t cause Anders to instantly vow to be an aviator. His love for planes would come much later. That love would result in awards and decorations including Distinguished Service Medals from the Air Force, NASA and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission; the Air Force Commendation Medal; National Geographic Society’s Hubbard Medal for Exploration; Collier, Harmon, Goddard and White trophies; and the American Astronautical Society’s Flight Achievement Award.

At that time, though, he had much more to think about. The day after the bombing raid, he and his mother were loaded onto a ship.

“We were the first to go down the Pearl River, after the Chinese had mined it,” he said. “In those days, you didn’t expect them to keep careful records of where they dumped the mines. It was sort of like Russian roulette.”

Anders caused extra excitement when he pulled a “bandit alarm” on the ship, meant to warn against river bandits.

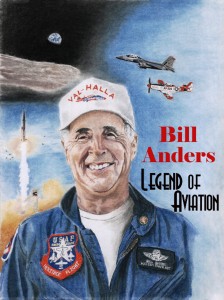

Maj. Gen. Bill Anders bases his P-51D Mustang, Val-Halla, and other Heritage Flight Museum aircraft, at Bellingham International Airport.

“On the ship, the Europeans were fenced off from the Chinese with barbed wire, because you never knew who was going to turn on you,” he said. “Alarms were all over the ‘genteel’ side of the ship. I climbed a fence and pulled one of them, which didn’t help the captain’s disposition.”

Anders and his mother would eventually make their way to the Philippines, where they would wait for word regarding his father.

Reunited

Bill Anders said that his father, assigned to the USS Panay, an American gunboat, never did like the movie that told the story about the men who patrolled the Yangtze River. In “The Sand Pebbles,” engineer Jake Holman (Steve McQueen) arrives aboard the gunboat USS San Pablo, assigned to patrol a tributary of the Yangtze in the middle of exploited and revolution-torn 1926 China. His iconoclastic and cynical nature soon clashed with the “rice-bowl” system that ran the ship and the uneasy symbiosis between Chinese and foreigners on the river.

“The movie showed the Chinese running those patrol boats,” he said. “Twenty years later, in the case of the Panay, the Navy had made sure the Navy was running the boats.”

Anders’ father was the number two in charge on the USS Panay when Japanese aircraft attacked the ship on Dec. 3, 1937, during hostile fire on the Yangtze River.

“The Japanese army had gone nuts, raping Nanking and shooting at random,” Anders said. “The ship’s mission, besides just showing the flag up and down the river, was getting missionaries, journalists and military people out of China.”

A bomb hit the bridge, wounding the captain and leaving Lt. Anders in charge of the ship.

“He was the gunnery officer, so he wasn’t on the bridge at the time, although subsequent bombs wounded him badly,” Anders said. “The captain was down in sickbay, badly wounded and suggesting they abandon ship. My dad said, ‘No, he’s not in charge anymore. I am.’ We think he was the first American naval officer to order open fire on the Japanese.”

Eventually, the Panay sank.

Bill Anders received the good news on his 30th birthday that NASA had selected him as part of the third group of astronauts.

“They stayed until the water got up to their knees,” Anders said. “My dad was one of the last off. Japanese fighters machine gunned them as they were going ashore. They hid in the reeds and later were helped by sympathetic Chinese villagers, for two weeks, before the British finally rescued them.”

Lt. Anders received the Navy Cross for his actions, but also had to be retired medically.

“He developed a staph infection,” Anders said. “In those days, that was nearly lethal. They didn’t have penicillin or even sulfur, and they couldn’t stop the infection.”

The wounded officer was sent to the San Diego Naval Hospital.

“He was called back to the military, even though somewhat impaired, during the Second World War,” Anders said.

During that period, Lt. Anders was a personnel officer of the Naval Training Center.

Bill Anders enters the Naval Academy

For a time, Lt. Anders was stationed in Vallejo, Calif. Once again, his son took notice of aircraft flying overhead.

“I’d see the P-38s out of Hamilton flying around,” Anders recalled. “I thought, ‘Boy that looks fun.'”

The aircraft attracted him, but not anymore than other military modes of transportation.

“I made a few aircraft models, but I also made models of tanks and Jeeps,” he said.

Anders attended Grossmont High School, in El Cajon, Calif., for his sophomore and junior years. There, he developed several friendships, in particular with fellow members of the tennis team. But his grades weren’t good enough, so he was sent to Boyden’s School, a military academy prep school near Balboa Park.

“It was basically a school where you spent all day taking Naval Academy tests,” he said.

Anders commuted to Boyden’s from La Mesa, Calif.

“It was kind of a tough commute,” he said. “I had to do it by bus.”

He thought the instruction was good, but he missed his friends at Grossmont. Again, aircraft interrupted his concentration.

“Consolidated Vultee was building the huge B-36, a 10-engine airplane,” he said. “They would come in from Fort Worth and fly over our school. We were right under the flight path. All the pencils would jump up and down on the desks, and that’s all you could hear.”

L to R, seated: Buzz Aldrin, Bill Anders, Charles Bassett, Alan Bean, Gene Cernan, Roger Chaffee. Standing: Michael Collins, Walt Cunningham, Donn Eisele, Theodore Freeman, Dick Gordon, Rusty Schweickart, David Scott, Clifton Williams.

When it came time for Anders to go into the service, it wasn’t a tough decision.

“It was sort of decided,” he said. “I had appointments to West Point, the Maritime Academy and the Naval Academy, but I selected the Naval Academy.”

Anders entered the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md., in 1951. He came home for summer vacation after the first year. It could have been a disappointing summer. He’d had his eye on a friend’s sister for years, but it was looking like she’d never return his affections. However, she did end up introducing him to his future wife, Valerie Hoard.

“She lined us up on a blind date,” he said.

Anders and Hoard were still dating when he took a Navy indoctrination cruise after his second year at the Naval Academy. That cruise caused Anders to give more thought to aviation.

“The ‘carrier cruise’ had a negative effect,” he said. “They had so many accidents and destroyed so many airplanes. But after I flew a couple of times in a Navy airplane, I liked it. The Air Force didn’t have an Air Force Academy at the time. The Navy was allowing 25 percent of the class, both from the Naval Academy and West Point, to be commissioned in the Air Force. Ten thousand feet of Air Force concrete runway seemed to be a lot better than a short carrier deck.”

He was further encouraged to look at the Air Force when a young general visited Annapolis and spoke of better advancement opportunities in that area.

“I went Air Force, and have been happy ever since,” he said.

The Air Force and marriage

Anders graduated from the academy in 1955, with a bachelor of science degree. Shortly after that, Anders and Hoard were married.

After being commissioned in the Air Force, Anders began flying the T-34 Mentor, which had a tricycle landing gear.

“I graduated to the Air Force T-28A,” he said. “Then I was in the first ‘all jet class,’ which meant we went to the T-33, the offshoot of the Shooting Star.”

After advanced training, Anders was assigned to one of the Air Defense Command’s all-weather interceptor squadrons. Stationed out of Hamilton Air Force Base near San Francisco, he flew F-89 Scorpions with the 84th Fighter Interceptor Squadron.

The Apollo 8 crew poses on a Kennedy Space Center simulator in their spacesuits. L to R: Jim Lovell, Bill Anders and Frank Borman.

“We were flying F-89Ds and F-89Js,” he said. “The F-89Js, in my opinion, were the best weapons for the Cold War, ever. They were heavy, sluggish fighters, with high tails, resembling Scorpions. They carried two nuclear-tipped, air-to-air missiles.”

The missiles could be very easily deployed.

“You had this first lieutenant and captain flying around over Santa Rosa with two nukes under the wing,” he said. “To launch it, the guy in the back just had to throw a switch; you pulled a trigger, and off it would go—a five-kiloton yield. It would have blinded everybody north of Ft. Bragg.”

While stationed at Hamilton, Anders became a father. Valerie Anders gave birth to the couple’s first child, Alan, in 1957.

“In those days, we had none of this Lamaze stuff,” Anders said. “You’d show up with your wife when her water broke, and the delivery nurse kicked you out, saying, ‘Come back later; we don’t need you.’ When I got kicked out, I decided to go flying. I was doing practice intercepts when I got a call from ground radar, saying, ‘Go afterburner to home plate.’ I asked, ‘What for?’ They said, ‘Your wife just had a baby boy.’ I said, ‘I still have half a load of fuel; why don’t I shoot a few more intercepts before I go?'”

Anders would have a chance to do a lot more practicing while stationed in Iceland for a year. There, with the 57th Fighter Interceptor Squadron (“The Black Knights”), he took part in early intercepts of the Soviet bombers that were testing America’s air defense capabilities.

“We were chasing Russian bombers,” he said. “I think I’m the first guy to give the famous Tom Cruise gesture to the Russians. We came up alongside, and they were waving, so I flipped them the bird. They waved and smiled.”

Russian intelligence later figured out what that gesture meant.

“About six weeks later, one of my colleagues came up alongside the Russians,” he said. “They put this sign in the window, which was apparently the supreme Russian insult: ‘We did a dirty deed to your sister.’ They were all laughing about it.”

After returning to Hamilton Field, Anders flew the F-101B Voodoos again with the 84th FIS.

“The Voodoo was quite a nice machine, except it had a nasty habit of pitching up if you went too slowly,” he said. “It wasn’t as good a weapon as the F-89J.”

Reaching beyond

While at Hamilton Field, Anders decided he wanted to be more than a fighter pilot.

“I thought I’d like to be a test pilot,” he said.

In order to become a test pilot, he needed to be accepted at the Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base. He made a trip to the base to talk to Chuck Yeager, who ran the school.

“He looked at my record and said, ‘Your flying time is good, but now the Air Force is looking for people with advanced degrees; why don’t you apply to the Air Force Institute of Technology?'” Anders recalled.

He applied to the Air Force Institute of Technology, at Wright-Patterson Air Force, hoping to take aeronautical and aerospace engineering courses. Instead, because of his excellent math grades at the Naval Academy, the Air Force was interested in him for the Airborne Nuclear Propulsion program and shuffled him into nuclear engineering.

Bill Anders participates in a training exercise in the Apollo mission simulator in building 5, in the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston.

“They had this wild idea of putting reactors in P-36s and flying forever on nuclear alert over the North Pole,” he said. “They envisioned me being one of the possible test pilots for that, so I became a nuclear engineer, specializing in radiation shielding. But when I graduated, they had already cancelled the program—thank God.”

Anders received a master’s degree in nuclear engineering in 1962 and was assigned to Albuquerque, N.M. He took over technical management of nuclear power reactor shielding and radiation effects programs at the Air Force Weapons Laboratory. That same year, he returned to Edwards to talk to Yeager.

“I said, ‘I’m ready; sign me up,'” he recalled. “Yeager said, ‘We’ve changed the criteria; now we want flying time.'”

By then, the school had made some changes. The United States was in a race with Russia to put the first man in space. The Soviets had already launched the first satellite and orbited the first human. In 1959, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, a civilian agency, had selected seven veteran test pilots as Mercury astronauts. In May 1961, Alan Shepard had become the first American in space. Shortly after that, President John F. Kennedy had challenged the U.S. to commit itself to landing a man on the moon, and in 1962, another group of nine astronauts joined the original seven.

In 1961, the Test Pilot School had begun a space course and the school’s name was changed to the Aerospace Research Pilots School. NASA began recruiting from the school’s graduates for its corps of astronauts.

Anders continued to wait for his chances at the school. One day in 1963, while he was driving his Volkswagen bus home from work, he heard on the radio that NASA was looking for a third group of astronauts.

“I didn’t pay much attention, because up until then, you had to be a test pilot,” he said. “But then I thought I heard them say you had to be a test pilot or have an advanced degree. I immediately pulled over to the side of the road. It was one of these 15-minute news things, interspersed with music. I sat there and listened to 12 minutes’ worth of music and advertisements, and sure enough, they came back on and said it was advanced degree or test pilot school.”

When Anders got home that Friday evening, he told his wife what he’d heard.

“Valerie has always been a real trouper and supporter,” he said. “We had four kids by that time. She was still nursing Gregory. She said ‘OK.'”

That evening, Anders wrote a letter to NASA and sent it to the address given on the radio.

“I told them I was just the guy for them—the world’s greatest pilot—and that I could solve their radiation problems,” he said. “I sent it registered that Saturday.”

On the following workday, after the usual Monday morning staff meeting, his boss made an announcement.

“He said, ‘Oh, by the way, for you pilots, NASA’s requesting applications for a third group of astronauts; here’s the form, if you want to fill it out,'” Anders recalled. “I thought, ‘Form?’ I went up to him later, and I said, ‘Boss, I’d like to fill out the form, but I’ve already sent a letter.’ He said, ‘Don’t worry about it; just fill out the form.'”

On Nov. 9, 1967, Apollo 4, the first test flight of the Saturn V, launched from Kennedy Space Center. On Dec. 21, 1968, Apollo 8 launched aboard a Saturn V. The crew was the first to ride on a Saturn V and to fly out of Earth’s orbit and around the moon.

Anders filled out the form and sent it in. He was surprised when he was asked to report for a physical.

“To my further surprise, I was asked to come back, and then, to my much, much, further surprise, I was asked to come back for a final interview,” he said.

Astronaut candidates were interviewed in San Antonio and in Houston, where the Manned Spaceflight Center would be built. Out of several thousand applicants, 30 were eventually selected for final screening.

“We figured they were going to at least cut that number in half,” Anders said. “We were all looking around at each other, wondering who it would be. I thought my chances were small.”

In 1963, Anders received a fantastic birthday present.

“On my 30th birthday, I got a call from Deke Slayton, saying, ‘How would you like to come work for us?'” Anders remembered. “I said, ‘I’ll be there!'”

NASA had selected Anders and 13 other men. Three days later, he got a call from Yeager, with news about his application as an aerospace research pilot.

“Yeager said, ‘I’m sorry to tell you that you didn’t make it, but you almost did; try again next year,'” Anders recalled. “I said, ‘Thanks, but I got a better offer.’ Yeager asked, ‘What do you mean?’ Keep in mind that Edwards’ test pilots looked down their noses at the early astronauts. They were taking a lot of the glory, but Edwards was doing a lot of the hard work. I didn’t know all that, so I said, ‘I got a call from Deke Slayton to come and join the astronaut school.’ Yeager said, ‘That’s not possible!'”

Anders said the conversation started “getting a little tense.”

“At the time, I thought he’d already sent me down the wrong road, costing me three years out of my life,” he said. “But it turned out it was the right road. I found out later that NASA was interested in the radiation work. When I told Yeager I’d been selected, he said, ‘I was the head of the Air Force screening committee. I reviewed all of the applications. We threw out any of our Air Force applicants who hadn’t been to the test pilot school.'”

Anders said that’s when he made a big mistake.

“I said, ‘Sir, it must have been that letter I sent them,'” he recalled. “Yeager asked, ‘What letter?’ I told him and he said, ‘You went out of the chain of command; I’m going to have that decision overturned.'”

Anders immediately called Slayton.

“I told him, ‘You’re going to get a call from Chuck Yeager; he wants me to get kicked out of the program,'” Anders remembered.

Anders believes that the friction between the Air Force and NASA helped his cause further.

“That just locked me in even tighter,” he said.

Gemini

In January 1964, Anders reported to Houston. His responsibilities included dosimetry, radiation effects and environmental controls. To prepare for space, the astronauts were subjected to courses in spacecraft systems.

“We were also given opportunities to learn geology, which I really thrived on,” he said. “Geology’s always been one of my hobbies. I loved that and volunteered to go on extra geologic field trips. That might have cost me, because that wasn’t considered quite the ‘right stuff.'”

While in lunar orbit during Apollo 8, Bill Anders took this famous picture of earthrise. Although it’s displayed here in its original orientation, it’s more commonly viewed with the lunar surface at the bottom of the photo.

While in training, Anders’ assignments included capcom duties for Gemini VIII.

“We were given increasing responsibility for our assignments,” he said. “I was in charge of the environmental control system engineering and designed the radiation dosimeter. But not being a test pilot in a gang of test pilots, I was a bit of a second-rate citizen. They treated me alright, but I wasn’t at the top of everybody’s list to fly.”

Initially, Anders was teamed with Neil Armstrong to back up Pete Conrad and Dick Gordon on Gemini XI. The main objective of Gemini XI was a high-altitude rendezvous and docking with a Gemini Agena target vehicle. Secondary objectives included practice docking and performing an extra-vehicular activity. Being on the backup team was disappointing, but the presumption was that Anders and Armstrong would rotate around and fly on Gemini XIII.

Gemini XI launched on Sept. 12, 1966. Gemini XII launched two months later, on Nov. 11, with the primary object of rendezvousing, docking and evaluating EVA. It would be the last Gemini flight.

“The Gemini program was so successful that they decided to terminate it,” he said. “They were satisfied the objectives had been met and shifted to Apollo.”

Apollo

Various factors went into who would fly which mission. However, not all those factors were known, so the astronauts constantly tried to figure out criteria for selection.

“We knew Deke Slayton would put guys on a list, and then he would just rotate them, from prime crew to backup crew and from backup crew to prime crew,” Anders said. “The non-test pilots generally were the last to rotate. It turned out that they put the more experienced crewmembers as either commanders of the flight or as command module pilots. The command module pilot would be by himself in lunar orbit and then come pick up the lunar module, after they had been on the surface.”

Anders said that in retrospect, the more junior you were, the better the chance you had of landing on the moon as a lunar module pilot. Being lower on the list didn’t mean you wouldn’t have an illustrious career.

“Alan Bean, although he was a test pilot and was the last assigned to a crew, ended up being on the second landing and flew one SkyLab,” Anders said. “He had a very distinguished career. Jack Schmitt and Charlie Duke were way down on the totem pole, and they landed on the moon.”

Anders’ position on the totem pole resulted in what appeared to be an early lunar landing position. Due to the cancellation of the Gemini program, Armstrong and Anders were the first two astronauts to check out in the lunar landing training vehicle. Anders really enjoyed the short helicopter-like flights. However, a mishap one day resulted in the LLTV program being put in abeyance for a while.

“One morning, I flew it in a successful flight,” he said. “Neil is a perfectionist, so he trained a little longer. He was trying to get it set up just right in a strong crosswind. Unbeknownst to him, one of the fuel sensors was out of whack, and just as he was about to touch down, he ran out of control fuel. He powered up and got altitude, and it started going around like a ruptured balloon at a birthday party. He managed to eject just as he was hitting the ground; he came right up out of the fireball.”

Apollo 8 splashed down on Dec. 27, 1968, in the Pacific Ocean, approx. 1,000 miles south-southwest of Hawaii. Frank Borman (left foreground), Jim Lovell and Bill Anders (right) are shown in the doorway of the rescue helicopter, aboard the USS Yorktown.

The program had many other delays and plan changes. The launch date of Apollo 1 was to be Feb. 21, 1967. But on Jan. 27, the U.S. space program came to a standstill when a fire on the pad took the lives of the prime crew: Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee.

Beyond the delay, the tragedy meant more shuffling. Among the changes, the backup crew of Apollo 1—Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele and Walt Cunningham—became the prime crew of Apollo 7. Anders and Armstrong were no longer teamed.

“Neil was down the line with Buzz Aldrin and Jim Lovell,” Anders said. “I was assigned to Apollo 8 with Frank Borman and Mike Collins.

Apollo 7, which launched on Oct. 11, 1968, tested the command and service modules on a Saturn 1B.

“Apollo 8 was an all-up test of the Apollo command, service and lunar modules,” Anders said. “We were going to be the first to ride on a Saturn V, but we were going to be in Earth’s orbit. We were to demonstrate rendezvous with the lunar module in high earth orbit.”

Borman would serve as commander, Anders as the lunar module pilot and Collins as the command module pilot.

During Apollo 8 training, however, the CIA and NASA worried that the Russians might try a circumlunar flight.

“They’d completed two unmanned ones, and we thought they were ready to do a manned one,” Anders said. “Much later, Alexei Leonov, who was going to be the commander of that flight, told me he was enraged at the Russian bureaucracy, because they didn’t have the guts to do it.”

That worry, and the fact that Apollo 8’s lunar module was behind schedule, resulted in NASA’s gutsy decision to change Apollo 8’s earth orbital mission to that of a circumlunar flight.

“That screwed my chances of being a lunar module pilot and landing on the moon,” Anders said. “I could see that coming. The booby prize wasn’t all that bad, though—being on the first flight out of Earth’s orbit and around the moon.”

Another change occurred when Collins developed a bone spur and Lovell took his place as command module pilot. On Dec. 21, 1968, Apollo 8 launched aboard a three-stage Saturn V. After traveling three days to get there, Borman, Lovell and Anders orbited the moon 10 times, during a 20-hour period.

While in lunar orbit, Anders took one of the world’s most famous photos.

“On our third orbit, we saw the earthrise,” he said. “We hadn’t seen it before. There was a big scramble for cameras. Borman was yelling, ‘Hand me a camera!’ I handed him a black and white camera, but not by design. I had the color camera. He shot the first earthrise picture, but I shot the color picture that became iconic. It’s credited with kick-starting the environmental movement.”

In lunar orbit on Christmas Eve, the crew made a memorable live telecast to a worldwide audience.

“One of Borman’s friends had suggested that if we wanted to do something serious, we should read the first passages of the book of Genesis,” he said. “We did that. It wasn’t really as a religious thing, but Madalyn Murray O’Hair sued us anyway.”

On the tenth revolution of the moon, the crew again lit off the service propulsion engine.

L to R: Apollo 7: Walt Cunningham, Donn Eisele and Walt Schirra; Apollo 8: Bill Anders, Jim Lovell and Frank Borman Standing: Charles Lindbergh, Lady Bird Johnson, Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson, NASA Administrator James E. Webb and Vice Pres. Hubert H. Humphrey

“That gave us the velocity to escape the grasp of lunar gravity and sent us back on a trajectory to Earth,” Anders explained. “We didn’t have to make a single correction, all the way back. In my view, that’s staggering, considering the puny computer we had, which was a fraction of what you have sitting on your desk.”

The crew splashed down in the dead of night on Dec. 27.

“We hit the water so hard, it temporarily knocked Borman out,” he recalled. “It knocked his hand off the jettison switch for the parachutes. We had quite a surface breeze; it pulled the spacecraft pointy-end down. Here we were, great lunar conquerors, hanging in our straps, showered by debris. Eventually, we inflated a couple of balloons up near the apex, and the spacecraft righted. When the sun came up, the crew in the recovery helicopters could shoot the sharks that were circling. The frogmen came in, picked us up and put us on the Yorktown.”

The Apollo 8 crew was given tickertape parades in Chicago and New York. Then Anders and his wife went to Acapulco, Mexico, for a little relaxation.

“I got some bad food and spent three days with my head in the toilet,” he laughed.

At the end of February 1969, the Soviets sent up their huge N-1 rocket, for its first unmanned test launch. But after several malfunctions, the N-1 blew apart, firmly putting Moscow out of the game.

Apollo 9, a 10-day Earth-orbital mission, launched on March 3, 1969, as the first manned flight of the Apollo lunar module. During the flight, commanded by Jim McDivitt, lunar module pilot Russell Schweickart performed a 37-minute EVA. David Scott was the command module pilot for the mission.

Although there had been a chance that it would touch down on the lunar surface, it was later decided that Apollo 10 would instead be a full dress rehearsal for Apollo 11. Apollo 10 launched on May 18, 1969, carrying Tom Stafford as commander, Gene Cernan as lunar module pilot and John Young as command module pilot.

Anders had been assigned to the Apollo 11 backup crew. Apollo 11 launched on July 16, 1969. Commander Neil Armstrong and LM pilot Buzz Aldrin landed in Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility), on July 20, while Michael Collins continued in lunar orbit. After triumphantly planting the American flag, Armstrong and Aldrin set up scientific experiments, took photographs and collected lunar samples. The LM took off from the moon on July 21 and the astronauts returned triumphantly to Earth on July 24.

Anders had rotated from Apollo 11 backup crew to prime crew of Apollo 13, but like many, he believed the U.S. had won the space race, and he thought that the Apollo program would consequently be truncated.

“When Buzz and Neil put that flag on the moon—and that’s what Kennedy said it was all about—my opinion was that the race to the moon had been won,” Anders said. “Why run around the track a few extra times? It was risky; if we lost somebody, it would wash out the success of the landing. I thought we needed to figure out how to bring this thing down to a soft landing.”

He voiced his opinion, and NASA Administrator Thomas Paine agreed.

“He asked me to come to Washington to work for the National Aeronautics and Space Council and shape a program to follow Apollo,” Anders recalled. “I did, right after the Apollo 11 flight was back.”

Fred Haise was chosen to replace him on Apollo 13. Lovell would serve as commander and Ken Mattingly as CM pilot. However, two days before the launch, Mattingly was removed from the prime crew because of exposure to German measles, and Jack Swigert replaced him.

Apollo 13 launched on April 11, 1970, but the mission was aborted after nearly 56 hours of flight. The loss of service module cryogenic oxygen led to the consequent loss of the capability to generate electricity or provide oxygen or water. When breathable oxygen began to run out in the command module, the three astronauts were forced to seek shelter in the small lunar module. With the help of Mission Control, the crew was able to gain control of the situation and return safely to Earth on April 17.

Apollo 14 and 15 launched in 1971 and Apollo 16 in April 1972. With the cancellation of Apollo 18 through 20, Apollo 17 would become the sixth and last Apollo mission in which humans would walk on the lunar surface. That crew would be Gene Cernan as commander, Ron Evans as CM pilot and Jack Schmitt as LM pilot. Cernan would take the last human steps on the moon on Dec. 13, 1972.

Life after space

Anders served as executive secretary for the National Aeronautics and Space Council from 1969 to 1973. The organization was responsible to the president, vice president and cabinet-level members of the council for developing policy options concerning research, development, operations and planning of aeronautical and space systems.

“I was with the council until we got the post-Apollo program,” he said. “That program included the shuttle. I was pushing for a small shuttle. With Nixon’s second election looming, a key staffer, Bob Haldeman, called me and asked, ‘Which shuttle will give us the most aerospace jobs in California?’ I said, ‘Sir, the big one.’ He said, ‘That will be it.’ The advertisement on the shuttle was that it would reduce the cost to orbit by a factor of 10. It increased the cost by a factor of 10. That’s a hundredfold error. So, we had a very powerful machine that didn’t nearly meet its objective, servicing a space station.”

In August 1973, Anders was appointed to the five-member Atomic Energy Commission.

“I had recommended that the Space Council be shut down, because we had done our job,” he said. “The Nixon gang was impressed by that, so they sent me on to the AEC. They were unhappy with the commission, because they had a lot of lawyers. I was the only engineer.”

Chairperson Dixie Lee Ray surprised several on the commission, including Anders, when she appointed Anders lead commissioner for all nuclear and non-nuclear power R&D. Anders was also named as U.S. chairman of the joint US/USSR technology exchange program for nuclear fission and fusion power. When some charged that there was a conflict of interest between the nuclear regulatory side and the nuclear development side, the AEC was split.

Following the reorganization of national nuclear regulatory and developmental activities, the Energy Reorganization Act established the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, in 1974. President Nixon named Anders to become the first chairman of the NRC. In January 1975, the agency took over the role of oversight of nuclear energy matters and nuclear safety from the AEC.

“I wanted to go into the development side, and all the lawyers wanted to go into the regulatory side,” Anders said. “The Nixon White House, in its perverse but maybe correct way, said, ‘What we don’t want are a bunch of lawyers institutionalizing this new Nuclear Regulatory Commission around themselves, so we’ll send Anders over there, because he’s not a lawyer and has shown some leadership and organizational talent.'”

Anders agreed to do it for the next two years. Following that period, a new opportunity presented itself.

“By that time, Watergate had happened, and Gerry Ford was president,” he recalled. “He was one of the best presidents we’ve ever had, but he couldn’t get reelected, because Chevy Chase made him look like a dope. One day, I was with a friend who worked at the White House. His job was to get ambassadorial appointments approved by the Senate. He said, ‘Bill, you’ve been confirmed three times already and are non-political. We need to fill some of these. How would you like to be an ambassador?’ I didn’t really want to, but I said I’d ask Valerie.”

After the Apollo 8 flight, the State Department had sent the couple around the world, and Valerie Anders had particularly enjoyed Norway.

“Valerie asked me to inquire if Norway was available,” Anders said. “My friend passed the information to Larry Eagleburger (who later became secretary of state). Although that ambassadorship wasn’t open, Eagleburger offered it to me anyway.”

Anders accepted the position and held it until 1977. That year, he left the federal government, after 26 years of service. He soon took a job at General Electric.

“Back when I was with the NRC, I had shut down 10 General Electric reactors in one day, because we had a deadline and the company hadn’t provided some information we needed,” he recalled. “I guess they thought I had backbone, because when I left the government, GE hired me to run its Nuclear Energy Products Division at San Jose.”

Anders joined GE in September 1977 as vice president and general manager, responsible for the manufacture of nuclear fuel, reactor internal equipment and control and instrumentation for GE boiling water reactors at facilities located in San Jose, Calif., and Wilmington, N.C. In addition, he had responsibility for the GE partnership arrangement with Chicago Bridge and Iron for the manufacture of large steel pressure vessels in Memphis, Tenn. In 1979, GE sent Anders to Harvard Business School’s advanced management program, to acquaint him further in financial management.

In January 1980, he was appointed general manager of the General Electric Aircraft Equipment Division, with headquarters in Utica, N.Y.

“I told them I really liked aviation, so they assigned me that division, which we made very successful,” he said.

Anders said he was in charge of all things related to aviation at GE except engines.

“Radars, guns, instruments, flight controls,” he said. “It was a multibillion dollar business.”

Then, Textron made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. Although somewhat reluctant, he joined the company as senior executive VP of aerospace.

“It turned out to be a mistake, because the CEO and I didn’t get along,” he said. “Making the company more profitable would have been relatively easy, but he wouldn’t give me the freedom to do what I’d learned to do at GE. The only good deal was that I was able to fly Bell helicopters, since that was one of my companies.”

In 1988, while at Textron, Anders retired from the Air Force Reserves, at the rank of major general. In late 1989, he left Textron, after General Dynamics Corporation offered him the position of vice chairman, with the promise of being chairman within the year, after the present chairman retired. As chairman, he had the authority to appoint himself “assistant test pilot” for the F-16.

“In December, the Berlin Wall came down, and then the market collapsed,” he said. “I showed up the first of January 1990, for this dream job. To his credit, the prior chairman had spent a lot of effort cleaning up some real scandals, but the financial situation had deteriorated.”

Anders became chairman in January 1991. By using relatively simple management techniques like selling low-performing divisions that weren’t doing well, General Dynamics started turning around.

“Warren Buffet liked what he saw and decided to invest in the company,” Anders said. “Before long, we became the darling of Wall Street. Warren gave me his proxy. I used that to pressure the other shareholders to follow on the Anders Plan. They all made a lot of money and the government was very happy, because the products were so good. But I was wounded from fighting, after three or four years of firefights, I decided to let my number-two guy run the place. I set up my replacement and then retired.”

Jim Mellor, the chief operating officer, took over as CEO. When he retired, Nick Chabraja, who had been outside general counsel, became CEO.

Anders retired as an employee of the corporation in 1993, but remained chairman of the board until May 1994.

“I gave them one year for the transition, so that Warren Buffet wouldn’t think the company was in trouble,” he said. “We made Berkshire Hathaway quite a bit of money.”

Home and the Heritage Flight Museum

Bill and Valerie Anders have called the state of Washington their home for more than two decades.

“When I was 4, my dad was on a battleship that went into the Bremerton Naval Yard,” he recalled. “They had to have the barnacles scraped off or something. We lived right on the water. It was in the summer, and it never rained. I had all the clams I could dig, all the berries I could eat and all the garter snakes I could catch. It was heaven for a 4-year-old. We left, but the vision of this place grew with me.”

In the mid-1980s, the Anders returned to the area.

“I found that the vision had shrunk; it wasn’t nearly what I remembered,” he said. “I was a little disappointed. We went up to the San Juan Islands and fell in love with the area. We eventually went back and bought some property. We were going to build a house, but then one that was right on the water came on the market. We really liked it, so we bought it.”

He said they still love the house and the area, but don’t like the area as much during the winter.

“We bought another house in Point Loma, California, near our daughter,” he said.

The Anders family spends a lot of time together, but that time isn’t spent at a golf course.

“We don’t play golf,” he said. “We’re a formation-flying family on the weekends.”

Bill and Valerie Anders have raised six children: Alan, Glen, Gayle, Gregory, Eric and Diana. Not all of the family members participate in that particular hobby, but they all work together on a project close to Anders’ heart: the Heritage Flight Museum. Anders’ commitment to preserving and flying yesterday’s warbirds, as well as his role in helping lead the Apollo space program to success, led to Anders’ enshrinement in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 2004.

Shortly after retiring from General Dynamics, Anders and his family established the Anders Foundation. Anders and his foundation have essentially been the sole supporters of the Heritage Flight Museum (www.heritageflight.org), a 501c (3) founded in 1996, dedicated to the flying and preservation of historic military aircraft.

The Anders family established the museum to help the public understand and appreciate the contribution that military aircraft and the people who flew them have made to American heritage, national security and freedom. The flying museum is presently located at Bellingham International Airport. The focus right now is to develop a permanent home to display and operate the museum’s aircraft. The Port of Bellingham, in conjunction with the staff at the museum, is working to keep the museum at BLI.

The museum is definitely a family affair. Bill Anders serves as president, Valerie Anders as secretary, Greg Anders as VP, executive director and webmaster, and Alan Anders as VP and director of maintenance.

“We drafted our children to get it off the ground; some of them work in the museum,” he said. “Some of them really don’t have much interest in aviation.”

Glen, Eric and Diana Anders serve on the board with their parents. Gayle Anders Nuffer and her husband, Carl, are also board members, as is Valerie’s nephew, Steven Hoard. Anders said they’ve started to get outside directors as well. He explains that when they go out of the family, they stick with aviators, such as Merrill Wien, the director of safety and training; Dr. Dydia DeLyser, curator and archivist; and Doug Johnson, a lawyer.

Anders’ vintage collection began after he coveted an aircraft owned by Borman.

“I bought a beautiful Beaver from Frank; he’d restored it in military colors,” he said. “Then Frank bought a Mustang. I said, ‘Gee, I’d really like to have one of those as well.'”

One day, as he flew over Borman’s house in Las Cruces, N.M., heading for Houston, Anders called Borman from his cell phone.

“He said, ‘Hey, Anders, I found a Mustang for you; get your ass down here!'” Anders recalled. “It was a few miles from Las Cruces. We drove there and I said, ‘I’ll buy it if you test it.’ So, he did; fluid was coming out of every old hose. He flew it over to El Paso, where it was restored.”

Anders raised eyebrows when he decided to race his North American P-51D, Val-Halla, during the 1997 Reno Air Races, for museum exposure. He raced it as race #68 (the year of the Apollo 8 flight).

His goal was simply to have some fun and get his feet wet by racing in the bronze races that weekend. To have better luck qualifying, they made one modification from stock: they installed a spray bar. Three five-gallon jugs of water, placed behind the seat, got them through the two qualifying laps.

“People laughed, because here was this old guy, a rookie, expecting to race with these ‘experienced’ guys,” he said. “I was sneered at, but I found out that some of the Reno Air Race guys aren’t very good pilots; they just have money.”

The remarks spurred Anders to make a further change. Overnight, his mechanic re-plumbed the Mustang, turning one wing tank into a water tank.

“After we qualified, he said that if we put water in one of the wing tanks, we’d have enough for all eight laps,” Anders recalled.

By the final race day, Anders had qualified to race in the silver class.

“It was an extremely rough day,” he said. “But to me, an old fighter pilot, it was just like a low-altitude bombing mission. You just tied everything down and held on. We started spraying water even before the start and continued all the way around. I came in third. Everybody was amazed.”

Anders raced the Mustang again in 1998 and 1999, but the best they did in those three years was the first race. Before the 1998 races, he acquired an F8F-2 Bearcat in England. In Wampus Cat, he placed second in unlimited bronze that year and fifth in 1999. He particularly recalls the fun he had racing David Price and Howard Pardue.

“David had a F8F-1; I had an F8F-2, which meant I had a bigger radiator,” he recalled. “David was a better race pilot, but he knew he was good for only a few laps. After that, he’d pull over, salute, and let me go by. Then I’d chase Howard Pardue, who had nitro in his F8F-2. Howard would just toy with me. I’d catch up with him, and he’d make the Tom Cruise maneuver and pump the nitro in there, and get a hundred yards ahead. Then a Sea Fury would just go ambling by, no matter what any of the Bearcats did. I thought it was ridiculous to continue racing a valuable and rare Bearcat.”

Anders put quite a bit of thought into naming his Mustang and Bearcat.

“When I was in Iceland, which is Viking country, my call sign was ‘Viking.’ Valhalla is Viking heaven,” he said. “I had told my wife I was going to name the airplane Venomous Valerie, but she didn’t go for that. So, we called it Val-halla. We dedicated the aircraft to the 57th Fighter Interceptor Squadron that had been stationed in Iceland until recently.”

The red wingtips and tail of the silver aircraft reflect the color scheme of the Nevada Air Guard’s first airplanes to Iceland.

DeLyser’s fiancé, Paul Greenstein, a western swing musician and historian, helped name the Bearcat.

“Paul said, ‘You need to call it Wampus Cat,'” Anders remembered. “In the early 1930s, Gene Autry had a song called ‘Bear Cat Papa.’ It’s about a rough-and-tumble guy—Bearcat Poppa—looking for a rough-and-tumble girlfriend—a Wampus Kitty. Wampus means crosswise or mean.”

Wampus Cat is no longer part of the museum’s collection.

“We recently sold it because it didn’t really fit our core theme,” Anders said.

That theme is U.S. Army Air Corps and Air Force vintage warbirds, including fighters, trainers and liaison aircraft. The museum’s signature aircraft is Val-Halla, but Anders said they’re not really focusing on World War II planes.

“We’re really concentrating on the largely unrecognized aircraft of Vietnam and Korea, like the O-1 Bird Dog, the O-2 Skymaster and the A-1 Skyraider,” Anders said. “We have aircraft flown on Sandy missions and by the Ravens. Our main emotional thrust is for those aircraft and pilots who flew them that don’t get enough credit.”

The museum’s aircraft include a PT-13 Stearman Kaydet, PT-19A Cornell, H-13 Sioux, L-13 Grasshopper and L-39C Albatross (Red Bandit). A Vietnam-era A-1 Skyraider, named Proud American, is dedicated to Bill Jones, a Medal of Honor winner.

“We’re checked out in all of them, and all of them are flyable,” Anders said. “Because of insurance, we delay annuals on some of them, but we can crank them up fast. I kid my friend Bonnie Dunbar, the Museum of Flight director, that more people see our airplanes than hers. They have a wonderful museum, but we do air shows; that’s our shtick. We also do flyovers for things like veteran burials and medal ceremonies.”

Once a permanent facility is established, the HFM will add exhibits highlighting elements of the U.S. space program—mainly the Apollo program. The museum plans to feature aviation restoration projects and models as well as aviation and space flight memorabilia, historical presentations and educational material. The museum also plans to develop youth education programs.

Anders, who has logged more than 9,000 flight hours and holds several world flight records, participates in both USAF Heritage Flight and USN Tailhook Legacy Flight programs. The Heritage Flights, part of the USAF aerial demonstration team’s air show programs, combine old and new aircraft in spectacular flybys. Witnessed by millions of aviation fans, the program has become a great recruiting tool for the Air Force.

Anders is one of the original and very few civilian Heritage Flight pilots that Air Combat Command has cleared to fly in formation with the Air Force’s modern fighters at air shows. He’s one of two pilots approved by the military for both programs.

The Air Force recently approved flying the museum’s A-1 Skyraider in its program.

“Greg and I both fly the Mustang and the Skyraider in the Heritage Flight program, and Alan and I fly the Skyraider in the Navy’s Legacy program,” Anders said.

For formation training, the Anders men fly North American T-6/SNJ trainers.

“I think T-6s are the best deal for formation flying,” Anders said.

Bill Anders usually flies the museum’s SNJ-4 that displays the number 55 (his Naval Academy class number), while Alan Anders flies the AT-6F Texan and Greg Anders pilots Hogwild Gunner, an AT-6D Texan painted in Idaho National Guard colors.

Greg Anders, assigned to the Idaho National Guard’s 190th Fighter Squadron, is the “new family fighter pilot.”

“He was a B-52 aircraft commander,” the proud father said. “He flew the F-15E Mud Hen and the A-10. He shot up tanks in Iraq and fought in the battle in Nazaria with the Marines.”

The family’s personal collection of planes includes the de Havilland Beaver, a Columbia 400 Anders recently acquired and two Brossards (French light military transport).

“Beavers are the world’s best beasts, but they cost more than a quarter of a million dollars,” he said. “A Brossard is stronger and flies almost as good, but it’s down in the $85,000 range. It’s a great airplane. We bought two of them, but we’ve decided now that’s one more than we need, so we have one up for sale. It’s really handsome.”

Anders also has a love for helicopters.

“I have a lot of helicopter time—that’s from NASA and getting ready for the lunar module,” he said. “We had our own JetRanger for a while. Now the museum has this little H-13 MASH-type helicopter. It’s really a nice replica; you can almost see Alan Alda standing next to it.”

Like many others who visit Barron Hilton’s Flying M Ranch frequently, Anders credits—or in this case, possibly accuses—his good friend for encouraging him to gain time in sailplanes.

“I go to the annual Hilton Cup event at his ranch. Thanks to Barron, after about six years of training, with about two flights a year, I was able to check out in sailplanes and get my rating,” he said, tongue in cheek.

Anders is proud of that achievement, but says he just isn’t a “great lover” of sailplanes. He has a simple reason for that.

“I like afterburners,” he said.

- This USAF Heritage Flight includes Bill Anders in Val-Halla, the HFM’s P-51 Mustang (middle), as well as Frank Borman in Su-Su II and an F-16 Viper.

- Shown at the Arlington Air Show in his WWII captain’s uniform, with his AT-6D Texan and the museum jeep, Greg Anders flies the HFM’s Mustang in the USAF Heritage Flight program.

- The HFM’s freshly painted Douglas A-1 Skyraider, The Proud American, sits on the snowy ramp at Bellingham International Airport.

- Alan Anders flies the museum’s Skyraider in the USN Tailhook Legacy Flight programs.

- The Proud American, flown by Alan Anders, unites with an F/A-18 E/F Super Hornet in a Legacy Flight formation.