By Di Freeze

In 1984, the Abbotsford Air Show, held east of Vancouver, drew so much attention that bumper-to-bumper traffic continued from the freeway to the airfield. In that traffic sat a pilot who was due to perform, and was now behind schedule.

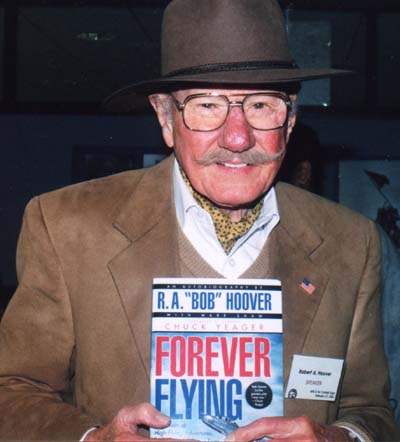

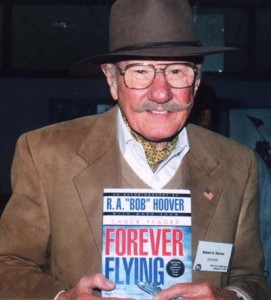

Bob Hoover, holding a copy of “Forever Flying,” which tells about five extraordinary decades of aerial escapades.

He constantly watched the sky, judging his launch time by who was now in the air. Suddenly, he rammed the car ahead of him, which had abruptly stopped, and that driver instantly leaped from his car and raced to the pilot’s window.

“Damn it, I just bought this brand-new Lincoln for my wife,” he exclaimed. “Worse than that, now I’m gonna miss seeing Bob Hoover fly!”

Although he was embarrassed, Bob Hoover introduced himself, apologized for the inconvenience, and invited the man and his wife to jump in with him. Soon, they were traveling through the VIP gate, towards the P-51 and Shrike Commander the legendary air show pilot would be flying that day.

Meet Bob Hoover

In more than 50 years of flying, Bob Hoover performed aerobatics in more different airplanes in more events in more countries and before more people than anyone in the history of aviation.

“I’ve performed in thousands of shows,” he says.

In “Forever Flying,” by R.A. “Bob” Hoover, with Mark Shaw, Chuck Yeager, Hoover’s good friend and sound-barrier-breaking teammate, refers to Hoover as the greatest pilot he ever saw and “a magician in the cockpit,” while astronaut Wally Schirra says he’s “the finest acrobatic pilot we’ve seen in our lifetime.”

“It’s like Bob’s wearing the airplane, instead of the other way around,” he said.

Fellow acrobatic giant Leo Loudenslager says Hoover set the “standard of excellence,” and Barron Hilton compares the pilot in flight to “poetry in motion.” Hoover’s even been praised by one of his idols, Jimmy Doolittle, who called him the “greatest stick-and-rudder man who ever lived.”

Hoover’s honors included being the first inductee, in 1995, of the International Council of Air Shows, which assists organizers with marketing and promotion over North America.

An introduction to the world of aerobatics

Robert A. Hoover entered the world on Jan. 24, 1922, in Nashville, Tenn., the youngest of three children born to Leroy Hoover, an office manager/bookkeeper at the local American Paper and Twine Company, and his wife Bessie, who ran a close-knit and religious family.

Hoover’s infatuation with aviation began with Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight in 1927.

“I was just five years old,” he recalled recently. “I saw pictures of him, and I started building little models.”

When he wasn’t building models of World War I planes, he spent time experimenting with anything mechanical. By high school, his love for aviation had grown to the point where he read everything he could about aviation, including newspaper clippings on Lindbergh, Roscoe Turner, Eddie Rickenbacker, Jimmy Doolittle, and other aviation heroes of the day.

“Doolittle was my idol,” he said. “I wanted to be just like him.”

He also read a remarkable book by an aviator named Bernie Ley. It introduced him to the world of aerobatics, detailing the aerodynamics involved and how each routine was performed.

“I studied the maneuvers until I knew every one by heart,” he said.

Often, Hoover would ride his bicycle to Berry Field, 15 miles from his home, where the Tennessee Air National Guard flew the Douglas 0-38, a biplane used for observation. One day he received an added thrill, when Roscoe Turner visited the field.

By then, Hoover was very familiar with stories of the pilot who often traveled with his lion, “Gilmore,” and he sought out an opportunity to be near Turner by wiping the windshield of his sleek Laird free of oil spots and bug stains. In return, Turner let him sit in the cockpit.

Turner’s flamboyance and attention to detail impressed Hoover.

“He always wore an immaculately tailored, bright British officer’s uniform, spit-polished black cavalry boots, a flashy tunic with gold buttons, sharply creased riding breeches, and a smart military officer’s cap,” he remembered. “He once said, ‘If you look like a tramp or a grease monkey, people won’t have confidence in you. A uniform commands respect; aviation needs it.'”

At 15, Hoover began taking flying lessons. He said it took him almost a year to build up the eight hours needed to qualify for solo flight, mainly because an hour’s worth of lessons cost eight dollars. Each Sunday, he pocketed his two dollars he’d earning for 16 hours of sacking groceries, and showed up at the airport for a 15-minute lesson in a Piper Cub.

Besides the cost of the lessons, he had a problem.

“I was nauseated every time I got airborne,” he said.

When Hoover did finally fly solo, he was pleasantly surprised to find that without his instructor, the plane flew better and he didn’t get as sick.

“Every time I found I could handle one maneuver, I went on to the next one, until I conquered the airsickness,” he said. “I did all sorts of aerobatics with airplanes that weren’t designed for it. I didn’t know any better, but I managed to do it without hurting them.”

He found out quickly that he loved to perform various routines, and was soon practicing harder maneuvers, like Cuban 8s, Immelmanns and hesitation rolls.

Joining the military

Hoover, who graduated from high school in 1940, said college was never a consideration.

“I didn’t realize the importance of further education,” he said.

On his eighteenth birthday, he joined the Tennessee Air National Guard. Although he was a tail-gunner trainee in the 105th Observation Squadron, some of the officers let him fly the Douglas O-38s, which had dual controls.

“I wasn’t eligible to go to the Air Corps flying school, because I hadn’t turned 21 and didn’t have the requisite two years of college,” he explained.

Still living at home, Hoover continued to buy flying time with the few dollars he earned in the Guard as a weekend warrior. In the meantime, the war in Europe had broken out. Although the United States hadn’t officially entered the conflict, the Tennessee National Guard lived up to the state’s reputation as the “Volunteer State,” and after requesting the privilege, went on active duty in September 1940. Hoover’s squadron was soon transferred to Columbia, S.C. While there, his unit was meshed into the Army Air Corps.

A change in regulations first appeared to be Hoover’s answer to his dream of going to combat and ultimately, becoming an ace.

“They lowered the age to become a pilot from 21 to 18,” he said. “As soon as that happened, the commanding officer of the squadron gave me an opportunity to become a second lieutenant and a pilot in the Air Guard. That would waiver your military training, because you get a check ride from these instructor pilots and then they pass you off. However, I found out suddenly that if I went through that routine to become a military pilot, I would have an ‘S’ in my wings, which would mean ‘service’ pilot, not combat.”

Intent on combat, he asked for and received an assignment for military flight training.

Primary training took place at a flying school south of Memphis, Tenn., in the small Arkansas town of Helena. Hoover reported in December 1941, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, where he was soon training in the Stearman PT-17.

On his first orientation flight, his instructor did a roll, and then asked him to try one. When Hoover completed a perfect one, the amazed instructor asked what else he could do.

Hoover proceeded to do a four-, eight- and 16-point roll, as well as other advanced maneuvers. The instructor soon approached the commanding officer, and told him he had a student who could fly better than he could.

“They cogitated a little and the commanding officer said, ‘Well, why don’t you have him get check rides, as if he needed it, but when he’s getting the check rides, he can show all the other instructors what can be done with the airplane?’ That’s what happened,” Hoover recalled.

Hoover’s flying was so superb that on graduation day, the CO asked the 20 year old to put on a 30-minute demonstration for the benefit of the other cadets.

“I was absolutely excited about that,” Hoover said. “I thought, ‘Well, I’m on my way now to being a qualified fighter pilot.'”

However, he went to basic training, at Greenville, Miss., and then to Columbus, Miss., for advanced twin-engine training.

“That meant you were going to get transports or bombers, and I wanted to be a fighter pilot in the worst way,” he said.

Back then, he said, short pilots were likely to go to fighter training, and taller ones to bombers and transports. At six feet, two inches, Hoover definitely had a problem. After graduating from advanced training, a visit with a sergeant in the personnel office who handled all the assignments changed his course in life.

“I took a fellow with me who was short; he wanted to go to transports and he had a fighter assignment,” he said. “I slipped a 20-dollar bill into the hands of this technical sergeant, and I said, ‘He wants transports and I want fighters.’ I knew he liked booze; I said, ‘Why don’t you go get some spirits for you and just switch those names, and everybody will be happy.’ He said, ‘You got a deal.’ That’s how I became a fighter pilot.”

Fighters

Hoover soon reported to the 20th Fighter Group, stationed at Drew Field, Tampa, Fla. After training in the single-engine AT-6 trainer, he advanced to the P-40, and then the P-39 Airacobra. He was soon putting the “Widow Maker” through a series of loops, rolls, and spins.

Another pilot who flew the P-39 at that time was Tom Watts, from Globe, Ariz., who would become Hoover’s closest friend in the service. Orders of a transfer to the European theater soon came, and although he was just a sergeant, Hoover was placed in charge of 67 pilots, “both officers and enlisted men.”

Hoover arrived in England in December 1942. His unit was sent to a small town called Stone near Shrewsbury, north of London. Shortly after arriving in Stone, his outfit received orders to report to a nearby airfield called Atcham.

He said they didn’t have any airplanes over there yet, so the British gave them “reverse land lease.”

“We flew Spitfires,” he said.

While at Atcham, the head of the reassignment group questioned why the enlisted pilots hadn’t received officer commissions.

“We had assumed we would be promoted before leaving New York, since we had learned that pilots preceding us, who were staff sergeants, had been,” Hoover said.

On Dec. 20, 1942, a brief ceremony was held. They were designated flight officers, a rank equivalent to warrant officer in the Army. It didn’t mean they were commissioned, but they got pay and privileges similar to those of commissioned officers.

Africa and testing aircraft, for the first time

The Allied invasion of North Africa occurred in November 1942. In January 1943, Hoover’s outfit was alerted it would be transferred there.

Hoover wasn’t happy when he found out he was headed to a supply depot in Mediouna. Even worse, they had been assigned to a replacement pilots’ pool.

“I thought I was going right to combat,” he said.

A few days after their arrival, the commanding officer, Col. John Stevenson, announced that a French major would be delivering and demonstrating a brand-new Lockheed P-38 Lightning. Although he had never flown the single-seater, twin-engine, twin-boom fighter before, Hoover was next to put the aircraft through maneuvers, since he had more twin-engine time than anyone else.

Determined to outperform the French pilot, on takeoff he put it through a series of low-altitude aerobatics.

“I was shutting down one engine and rolling into it, which is a no-no,” he said. “Then I started up again, and then shut the other one down and rolled in that direction; that’s a real no-no. Then I started to do things with just one engine.

“When I landed, everyone crowded around the airplane. The colonel reprimanded me in front of everybody, as he should have. He said, ‘Young man, I want to see you in my office, immediately.’ I thought, ‘He’s going to ground me.’ When I knocked on the door, he yelled, ‘Come in,’ and by the time I got through the door, he was out of his seat and he had his hand stuck out. He said, ‘Young man, I’ve never seen anything like that in my life! I have 300 hours in that airplane; I’d kill myself if I tried to do that!”

Hoover said he was officially grounded from that airplane, but told he could fly others.

“He said he couldn’t have pilots trying to duplicate my flight,” Hoover said.

Hoover took the opportunity to bring up the subject of a possible transfer to a combat unit, not only for himself, but also for Watts. Stevenson said he would get the first set of orders. However, when they came through, he found himself testing aircraft.

At places including Oran and Oujda, Morocco, he became familiar with the new P-40, as well as the P-39, and tested Spitfires and Hurricanes.

“I was so unhappy I could hardly stand it, but as I have looked back on it afterwards, it was the greatest learning experience in the world,” Hoover said. “I was flying so many airplanes that it gave me invaluable abilities to fly, because I had every kind of emergency you could think of and I learned to be so quick in my thinking.”

Part of Hoover’s job was to test-fire weapons as well. To do so, he would often fly in and hit a series of ground targets.

“I became so skilled that I could hit targets upside down as well as right-side up,” he said.

He also practiced until he could do four perfect consecutive round loops, and accurately fire the guns at the targets at the bottom of them.

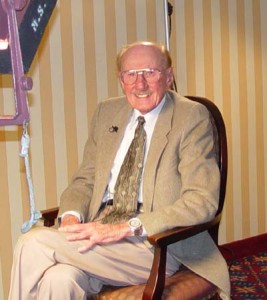

At the Society of Experimental Test Pilots’ symposium and gala last year, which celebrated a century of flight, Bob Hoover told his story for the record. That day under the spotlight wasn’t the first time he’d been “interrogated.”

Although he had a couple of narrow escapes before, Hoover’s most serious incident at the time occurred in the Vultee Vengeance A-3 1, a light attack bomber. During a routine test flight, each time the landing gear was lowered, and the throttle was reduced to idle, fire spewed out around the cowling next to the exhaust stacks.

Worried that this condition (known as torching) might occur when the plane touched down, Hoover did a flyby, but when the ground crew didn’t notice any problem, climbed a few thousand feet and completed his tests. When it was time to land, a large explosion jolted him in his seat, and blew away the bomb-bay doors.

Completely engulfed in flames, Hoover told his mechanic to jump. After briefly hesitating, he did, but when Hoover looked back to make sure he was safely out, he was dangling over the side of the plane.

“His parachute harness had caught on the stowed .30-caliber machine-gun mount in the rear cockpit,” Hoover said.

Hoover rolled the plane to shake the sergeant loose; as he floated off, knowing he was too low to parachute, Hoover added full power and rolled the plane from its inverted position, to extinguish the fire. Then he climbed to 10,000 feet and shut off the fuel supply, before dead sticking back toward the field. On final approach, the aircraft burst into flames. Hoover set it down, jumped out and ran.

The Distinguished Flying Cross

By early 1943, Watts was already with the 52nd Fighter Group, in Palermo, Sicily, and Hoover was anxious to be off as well. One day, he thought he might have a chance to plead his case, when he spotted a major he thought he had met while in England.

However, when he slapped Major Melvin McNickle on the back, he initially received a blank stare, before the man grinned. It turned out he was Marvin McNickle, the major’s twin brother. That didn’t stop Hoover from sharing his disappointment about not being in combat with him, once he discovered the mistaken identity.

As luck would have it, this McNickle, also a major, was on his way to take over the 52nd. After listening to Hoover’s story, he said that if he succeeded in getting a transfer, he’d back him from the other end.

But Hoover was ordered to report to the Twelfth Air Corps headquarters in Algiers, which was organizing a ferry command. Their commander, Colonel Eppwright, had requested Hoover for his operations officer. Hoover was bitterly disappointed to be checking out pilots in airplanes they had never flown before, and later, leading them in a North American B-25 Mitchell bomber to where he wanted to be—airstrips on the fighting front. He also brought pilots back to Algiers to pick up planes that would replace those lost in combat.

Months after his encounter with Major McNickle, he flew a B-25 bomber to lead six P-40 fighters to Licata, immediately after the invasion of Sicily. His mission was to escort the fighters over and then transport the pilots back to their home base at Algiers.

While he was in the operations tent filling out paperwork, a two-star general, Joe Cannon mistook him for one of the combat pilots and asked him how his mission had gone.

“I said, ‘Sir, could I take you outside and tell you about the mission?’ Hoover recalled. “We got outside the tent and I told him I had just led these airplanes over here from Africa, and everything I’d done. I said, ‘All I ever wanted was combat. I have enough time now to go home, but I don’t want to go home. I came here to fight.’ I told him how skilled I had become.”

He added that he really wanted to join the 52nd, and that Maj. McNickle had invited him to join him if he could get a transfer.

“He said, ‘Young man, you’ll have your orders within two weeks, if you told me the truth,'” Hoover recalled.

About three weeks went by without any word.

“I thought somebody must have told him I fibbed to him,” Hoover said. “Then finally, a corporal who was a clerk for the colonel I was reporting to told me he had been sitting on orders for me to go to 52nd Fighter Group for over two weeks.”

Hoover confronted Eppwright, saying he’d received a call from headquarters, wanting to know why he hadn’t reported for duty in Palermo.

“He told me he knew there was a big chance I’d be shot down, and that he was just trying to save my life, and that if I stuck with him, I’d be quickly promoted, and before the war was over, I’d have any assignment I wanted,” Hoover remembered.

Finally, Eppwright told him he could leave after he checked someone out in the B-25 to take over his responsibilities.

The next day, as he was preparing to check out two pilots, that same corporal raced up with copies of his transfer orders. Not wanting to hang around and give Eppwright a chance to reconsider, Hoover headed straight for Boco de Falco Air Base at Palermo.

“Palermo had just fallen into our hands,” Hoover said. “I put my footlocker in the back end and I got in the pilot seat. These fellas said, ‘Where are we going?’ I said, ‘Palermo.’ I wheeled up in that B-25, took my footlocker out and said, ‘Fellas, you’re checked out. So long!'”

Fourth Fighter Squadron, 52nd Fighter Group

Nearing his twenty-second birthday, Hoover joined the 52nd Fighter Group in September 1943. Assigned to the Fourth Fighter Squadron, his initial duties involved escorting Allied ship convoys carrying much-needed supplies. To the newly designated combat pilot’s disappointment, those excursions never resulted in any dogfights with the enemy, and he soon became restless again.

Then one day, Colonel Blair, his commanding officer in Casablanca, called McNickle to see if he would be interested in retrieving a B-26 Martin Marauder that had been shot up, and had bellied in on a short stretch of beach in the Straits of Messina. The forces back at the base needed the damaged plane, which had been repaired, but no one felt they could get it airborne since it was in a small, narrow, obstructed place. Also, there was no equipment in the area with which to disassemble the bomber.

The challenge intrigued Hoover, who had never flown the Marauder. He and a mechanic flew an L-4 reconnaissance plane over to look at the bomber, which they found on a crescent-shaped stretch of sand just a little more than a thousand feet long. A 12-foot drop-off to the water at one end meant it would be a challenge to lift the aircraft off the uphill-grade portion of the beach before it plunged over the drop-off into the Straits.

Hoover, who had studied several manuals describing the plane’s capabilities, knew they would need to lighten the aircraft. Two days later, the mechanic and a crew of 10 men began removing the copilot’s seat, most of the instruments and everything else that wasn’t essential to flying the plane.

Getting everything right for the recovery effort took more than a month. Finally, Hoover took off, with less than a hundred gallons of fuel in the tanks. He only had about four feet of clearance on each side of 600 feet of steel matting that now covered the sandy beach, as well as a 300-foot extension of chicken wire beyond that, so he had to get up to speed and steer the aircraft straight ahead. The slightest drift to either side would’ve been disastrous, but with the end of the beach quickly approaching, Hoover lifted the nose of the B-26 upward, and was soon on his way toward Palermo.

His mission was victorious, and Hoover would soon be rewarded with the Distinguished Flying Cross for his effort.

When orders came for the 52nd to relocate to Corsica, it was decided that Hoover would fly an Italian Fiat to the new base. When the Boco de Falco airfield had been captured, the vintage World War I aircraft had been discovered behind a damaged hangar. Hoover and some of the base mechanics soon began restoring the single-seat, high-wing monoplane.

“We put a second seat in it,” Hoover said. “I told Colonel McNickle, ‘We don’t have any way to get the mail. I can put another cockpit—baggage area—in the airplane and we can haul the mail to the different squadrons.'”

Hoover told McNickle that traveling to Corsica in the aircraft would be tricky, since he only had a float compass and no navigational aids, and if he missed the island, he’d be in “German territory.”

“He said, ‘I know how we can overcome that. We’ll just make a fingertip formation and that way we’ll be spread out so far you’ll see us go over and know which way to go,'” he recalled McNickle saying. “Because the wind’s going to shift while I’m out there at sea.”

When Hoover finally saw land, it was the southern tip of Sardinia.

“I started looking for some place to land and I found this big airfield,” he said. “The Italian Air Force had surrendered. But these people didn’t have anybody to surrender to.

I landed there, and they greeted me royally. They said, ‘We surrender.’ I said, ‘I can’t accept this. I have to be up in Corsica; all I’m asking for is some fuel and something to eat.’

Hoover estimates he was near the edge of the island of Corsica when a flight of P-38s thought he was an enemy plane, and came toward him, but overshot him.

“They were going so fast they couldn’t slow down to shoot at me,” he said. “I was just wagging the wings, and pointing to the American insignia on the side of the airplane by the cockpit.”

It won’t happen to me

On Jan. 24, 1944, Hoover’s twenty-second birthday, he lost his roommate and best friend. After being shot down near the coast of Calvi, Corsica, Tom Watts had successfully bailed out of his Spitfire, but the force of the high winds dragged him into a reef of rocks offshore.

“He bailed out and the wind was blowing so strong it drug him until it drowned him,” Hoover said. “The chute finally sunk with his body. I went out and flew over where he went down.”

Although this loss hit Hoover hardest, it wasn’t the first for his band of men. Still, Hoover was confident he could never be shot down.

A little over two weeks later, on Feb. 9, 1944, Hoover, who had been promoted to flight leader by that time, took off from Calvi, heading a four-plane-formation mission of Spitfires to patrol the waters off the Italian and French coasts, between Cannes and Genoa.

Hoover was flying “Black 3,” a supermarine Spitfire Mk. Vc, on a “harassment mission” to search and destroy attacking enemy ships, and shoot up trains. After Hoover and his fellow pilots had successfully destroyed a German freighter in the harbor near Savona, Italy, they flew to home base to refuel, and then returned to patrol.

A little while later, Hoover caught sight of four German Focke-Wulf 190s. Once he had identified the enemy, he quickly called out their position. When he saw that one of the FW-190s was on the tail of James “Monty” Montgomery, a friend who had been shot down a few months earlier, and had spent three days in a life raft before being rescued, Hoover frantically called out for him to break left to avoid gunfire.

Then, knowing he would need all the speed he could get, Hoover quickly pulled the handle that would rid his aircraft of its external fuel tank, but it came off in his hand.

“That’s high drag,” he said. “It really slows the airplane down. I was flying one of the early Spitfires, the Mark 9s, before, but the British took the 9s back and replaced them with 5s. It only had 1,100 horsepower; the other one had 1450. It’s a lot of difference. It was only capable of doing 215 mph and the airplanes that I was engaged with had a capability of 350 mph. It’s like racing a Model T Ford with a Cadillac.”

With the Spitfire’s superior turning ability now his only defense, he headed straight for the German fighter, spitting out a burst of .50 caliber gunfire, and then saw billows of smoke streaming through the sky.

He excitedly realized he had hit the FW-190’s engine, resulting in his first kill of the war. However, there was no time to celebrate. Montgomery had been hit, and Hoover watched his aircraft burst into flames and spiral toward earth.

And now, two FW-190s were after Hoover. As he dove left to avoid them, he noticed that his two other friends nearby, which he had been counting on to help him, had veered off and left him to fend for himself.

Although it had seemed unlucky at the time, the external fuel tank that wouldn’t jettison made Hoover’s Spitfire so slow that the F-190s overshot him. Unfortunately, two more turned in toward him.

Able to turn inside them, Hoover fired and hit one of the FW-190s. Just when he thought he was going to escape, shells hit his engine cowling from underneath. An FW-190 pilot had hit him with a high-angle deflection shot.

“Every time someone would come at me, they’d have so much speed they’d just go right on by, and they couldn’t hit me,” he said. “Well, these fellas were all running up my backend. Then they’d have to brake again. So, I saw this airplane, 90 degrees out here, and I just ignored it; how could you ever get an angle shot like that?”

As soon as the shells hit, Hoover felt severe pain shoot through his lower body. When he glanced in the rearview mirror, he saw another FW-190 closing in on him. After swooping in underneath him, the enemy pilot—most likely believing he had no firepower—pulled up in front of his nose, and Hoover hit him with a burst of gunfire.

However, he never knew whether he hit him or not, because seconds later, his engine exploded, and a ball of flames engulfed the nose of his Spitfire.

“I called and told the British patroller, “I’m going to have a mayday, because even if I get out of this battle okay, I won’t be able to get home. I’m going down at sea, so alert the Dumbos (walrus amphibian rescue plane) to start flying,” he recalled saying.

Then, he opened the cockpit, released his shoulder and seat straps, rolled the plane, and pulled his parachute’s ripcord. He continued to try to open his parachute, to no avail, until, only three or four hundred feet above the water, it blossomed.

His luck didn’t hold out, though, because his life vest, riddled with shrapnel, wouldn’t inflate, and when he hit the cold water, he felt immense pain on his wounded legs and buttocks. As he floated in the icy water, about 20 miles off the coast of Nice, France, he saw four Spitfires approach, and began to wave and splash. However, his enthusiasm died down when a group of FW-190s swooped down on them, and one was shot down and the others took off.

About four hours after he’d been shot down, Hoover had hope when he heard a faint sound in the distance. That hope was shattered when he realized the vessel was a German corvette. He would later learn it had been searching the icy waters for two Luftwaffe pilots.

Prisoner of War

After being pulled into the corvette, Hoover was strip-searched, and then given dry clothes. Later that evening, the ship docked at Nice.

Bob Hoover in front of the Martin B-26 Marauder he rescued from the beach at the Messina Straits in Sicily during World War II. Hoover was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for that remarkable feat.

Onshore, the German guards escorted him to a waiting car, and he was taken to a local jail. Even though he had been searched, no medical attention had been given to his shrapnel wounds.

“I was hit from the bottom and some of the rounds came in through the cockpit and out the top,” he said. “Fragments of metal got into the backs of my legs and my private parts. It wasn’t anything at that time; they were just flesh wounds—nothing that could be serious at all.”

Hoover was transported to the Continental Hotel in Cannes, which was the headquarters for German officers. There, when the commander asked him about his wounds, he answered as he had been taught, and as he would continue to answer to all other questions: “Robert A. Hoover, Flight Officer, 20443029.”

After the lengthy, futile interrogation, Hoover suffered the humiliation of being strapped to a marble column in the lobby, where civilians passing by spat at him, or physically abused him.

Two days later, he was transported down the southern coast of France toward Marseilles. There, he made his first of several escape attempts, but all that attempt did was get him confined to a dark basement cell.

The next morning, he was herded into a train compartment, with two guards, and was soon heading north, toward Switzerland. Again, Hoover tried to escape. Near the Swiss border, he slipped out a small bathroom window, dropped into a huge snow bank, struggled to his feet, and made his way along the tracks. But when he heard gunshots, he put his hands up, and guards soon surrounded him.

When they arrived at the German Luftwaffe interrogation headquarters, located several hundred miles north of Mulhouse at Oberursel, near Frankfurt, Hoover was put in solitary confinement. Over the next week, he would be questioned several times. Due to his obstinacy in refusing to provide information, he was finally taken to a cement wall riddled with bullet holes in a small courtyard, where a frustrated German captain addressed him.

“He said, ‘You still have a chance,'” Hoover recalled. “I said name, rank and serial number. They stood me against the wall and I thought, ‘Well, it won’t hurt for very long.'”

As the captain began a countdown, Hoover’s eyes began filling with tears, as he thought how he was going to die alone—and humiliated. He heard “ready” and “aim,” and then waited for the inevitable “fire.”

“Then, the captain said, ‘Drop your guns,’ to the Germans, or whatever he said,” Hoover recalled. “They took me back in and he said, ‘I don’t know why you’re so stubborn. We have all the information on you and the gun camera film shows your airplane. I’ve already told you your code signs and everything, and you haven’t acknowledged any of it. Why are you torturing yourself?’ I just kept saying name, rank and serial number. They put me back in the cell.”

Hoover said the Germans eventually did learn additional information about him, but he wasn’t the one who gave it to them. He was furious knowing someone wasn’t able to hold his tongue.

“I learned a lot from the British,” he said. “They were real disciplinarians about how to conduct yourself. For one thing, you’d just sit there with your head pointed to the ground, so they couldn’t see the expression in your eyes.”

After realizing the courtyard episode had just been a ruse “for the weak at heart,” Hoover was even more determined to escape, and he continued to try. After one attempt, he was kicked repeatedly, resulting in head and facial injuries that left permanent scars.

Up until that point, the Germans still hadn’t offered to treat his injuries, which, although not serious in the beginning, were now infected. Finally, his interrogator did ask about his injuries, and told him to drop his trousers. When Hoover obeyed, it revealed that his testicles were swollen and his groin was red and inflamed.

“He said he thought I had syphilis, but that they weren’t going to treat me. I thought, ‘Well maybe I have!’ I had been having a lot of fun,” Hoover chuckled. “But it was actually blood poison. They didn’t treat me until I got to the main prison camp.”

The next day, Hoover was taken to the train station, for a trip toward the Baltic Sea, and Barth, the location of Stalag Luft I. He and other POWs were stuffed into a boxcar in the marshaling yards near Frankfurt.

“We were taken there while it was still daylight,” he said. “We were locked up in the boxcars, and the British were bombing overhead; the marshaling yards were their target. There were little cracks in these old cars; one of the POWs in the boxcar, who was British, had been the lead navigator on some night flights a few weeks before. He said, ‘I say, old chaps, it looks like we’ve had it. We’re the target.'”

Hoover explained that prior to bombing, the lead Allied bomber would drop a spiraling flare, or “pathfinder.” Loads were then dropped as near to the pathfinder’s position as possible.

“He saw the flare fall, through the crack in the car,” Hoover said. “Everybody got down on the floor except this fella and me. I was asking him about his raid, and we just continued talking. Everybody was praying, bombs bursting all over the place. The guards all went to the air raid shelters and left us there to die. Part of my train was blown up, but there were no people in that part.”

Although those in his boxcar were unhurt, the fourth car down from them, packed with prisoners, was hit.

“It exploded, killing everyone inside,” Hoover said.

Finally, they arrived at Stalag 1. To discourage escape attempts, double 10-foot barbed-wire fences surrounded individual compounds, while another similar fence enclosed the entire camp. POWs were also aware that if they crossed a “warning wire,” they would be shot. On top of that, searchlights mounted on the guard towers illuminated the entire area.

Although guards boasted that no one had ever escaped from Stalag 1—or maybe because of that—Hoover, who would lose nearly 50 pounds during his stay there, and many fellow “Kriegies” continued what he called their “obsessive pursuit of freedom.” Hoover said he tried to escape at least 25 times. As a result, he spent a lot of time in solitary confinement.

Some of that time Hoover actually enjoyed, since the person in the cell next to him was Col. Russ Spicer, who became an inspiration to his fellow POWs, when, within earshot of German officers, he gave a bold speech regarding Nazi atrocities, and reminded the prisoners not to get too friendly with their captors.

Spicer was court-martialed by the Germans and sentenced to death, but the sentence wasn’t carried out.

“Russ was my hero,” Hoover said. “We spent long nights talking through the walls.”

In early spring 1945, believing the war was almost over, Allied Supreme Commander Gen. Dwight Eisenhower issued orders to POWs.

“He told the people that were going on missions to pass the word that we were not to escape after a certain point in time,” Hoover recalled.

By that time, said Hoover, there were 10,000 prisoners at Stalag I, a significant increase from the approximately 1,200 who were there when he arrived.

Despite Eisenhower’s directive, Hoover and others still kept trying to devise ways to escape.

“I had been on an escape committee. We’d been trying for so long that all I lived for was to get out,” Hoover explained. “We were dedicated, digging tunnels and running at the fence. I once got caught hanging on the barbed wire. Dogs were nipping at my feet; I really was scared. But I’d been working so hard at it, I wasn’t about to quit.”

In April 1945, Hoover and several others felt they had a good chance to escape.

“The guards started deserting, because the Russians were getting closer and closer,” he said. “We could hear the cannons going off.”

Hoover had been a POW for 15 and a half months when he made his last escape attempt. His partners in the scheme were an American named Jerry Ennis, from the 52nd Fighter Group, and a Canadian airman named George.

“We found a board underneath one of the buildings,” Hoover said. “I got a bunch of people that had worked on the escape committee to create a diversion. They started fighting on one side of the compound, and the guards were all looking over there. We ran out from under a building with this plank, put it up over the top of the fence and climbed out.”

Hoover said the three of them went through the woods on the peninsula where the prison camp was located, and began gathering dead wood and grapevines.

“We tied it all up and made a raft out of it,” he said. “Jerry was on the raft. The other two of us took off our clothes, and gave them to him to hold. The Baltic Sea is cold; we were in that cold water pushing this thing across. We had to go some distance, maybe 2,000 feet, before we could get to the other side of this little inlet.

“We got over there all right, and the Canadian fella thought he’d be better off by himself. Somebody had to make the decisions, and I was making them; he didn’t agree with me. He said, ‘I think it would be better if I went on my own.’ I said, ‘That’s your call.’ Off he went.”

That night, they stayed in a deserted German farmhouse, under hay in the barn. The next morning, they arrived at a small village.

“We stole two bicycles,” he said. “Now we were really mobile. We kept heading west; we got right in the middle of the Russian lines. They were still fighting the Germans and killing them like you can’t believe. Oh, it was just slaughter—the ugliest scene you could ever imagine.”

Since they were “considered” Allies, Hoover and Ennis, who spoke fluent French and could communicate with the soldiers who knew that language as well, spent the night with one group of Russian soldiers. The next day, another group, drunk and friendly, stopped them at a nearby village, and invited them to follow them toward a church.

When they entered the structure, they saw hundreds of German women and children huddled together. A little while later, Ennis told Hoover that the Russian soldiers expected them to each choose one of the women for the night. Hoover and Ennis worked out a plan, and Ennis told one of the women who spoke French not to be afraid; they would find a secluded corner, and if the Russians looked like they were coming over to “investigate,” they would “fake” the act expected of them.

Later, Hoover and Ennis arrived in another German village, where a distraught elderly woman with a bloody cloth wrapped around her hand asked if they were Americans.

“She said, ‘Look at this,'” Hoover recalled. “Her finger had swollen, from her wedding band, and they couldn’t get the ring off, so the Russians cut her finger off and took the ring. She said, ‘I want you two young men to remember this forever.’ She took us in a department store and every person that was in there had his throat slit. Then she said, ‘I want you to hold this forever. I want you to go down the road with me.’ Here was a big thing, like what you capture water in and drain it off the city. There were hundreds of bodies in there; they all had their throats slit.

“They had no mercy. Later on, we went into a farmhouse looking for food, and the Russian soldiers were there. They didn’t pay any attention to us. I watched them; they were all sitting in the bathroom, and one was standing up pulling the cord. He’d never seen a toilet. The shock troops that the Russians had were totally ignorant.”

While Hoover and Ennis traveled on their bicycles from one place to another, they made sure to avoid revealing they had ever been POWs.

“The Russians never believed in being captured,” he said. “If you were captured, you were considered a collaborator. Those that were ever captured knew that they would be mistreated enormously when they got back to their country. We knew the philosophy of the Russians by then, so when they would ask us what had happened to us, I would say, ‘We were shot down over Berlin and we’ve been evading ever since.'”

Hoover said they eventually ended up at a compound of farmhouses, surrounded by large walls, where over 50 people were staying. Those people, he said, had been forced to enter conscripted labor when France fell to Germany, and were now trying to flee the Russians. Besides the French, a few Germans were staying there as well.

“These people were all trying to get back home,” he said. “They were all very friendly. Since Jerry could speak fluent French, they opened their arms to us. They had some food, so they fixed up a dinner for us. That night, we were sleeping in a hayloft and we heard this horrible noise and a tank came right through the wall of the compound. We could hear them talking in Russian; they went running around looking for people or anything they could take.

“They came into the barn and I heard somebody scream. They went into the hay with a pitchfork. When they finally came over near us, we stood up and held up our hands. Jerry started talking in French to see if any of them could understand. Eventually we found somebody who could understand a little bit. We explained to him that we were Allies and had been evading and were trying to get back to our lines. They didn’t kill us, but they killed most everybody else. I’ve never been so terrified in my life.”

Up, up and away?

Hoover and Ennis left that area as soon as they could. Hoover couldn’t have been more thrilled when they later came across an abandoned Luftwaffe air base, just inside the border of Germany, deserted except for a few ground crew.

All over the airfield were revetments, created to hide aircraft. As they went from one revetment to another, looking for an aircraft that might be flyable, they were surprised to be totally ignored.

“People didn’t pay any attention,” he said.

Although they discovered at least 25 Focke-Wulf 190s, things at first looked grim for an air escape.

“The airplanes were all shot up,” Hoover said. “I finally came to one that had a lot of holes in it, but not in any of the vital organs. The thing I was worried about most was finding an airplane that was serviced.”

Although he had never flown a Focke-Wulf 190, Hoover said he knew a little about the aircraft.

“There was a fella in the prison camp whose orders were to go to England and evaluate the captured German airplanes the British had,” he explained. “He talked one of the lead generals over there into letting him fly a mission, and was shot down on the first one.

“I got to visiting with him one day, and I told him that I wanted to go to Wright Field after I got out, and that my commanding officer at the time I was shot down assured me he would do everything humanly possible to make that happen. He said, ‘I’m from Wright Field!’ He told me his whole history. He had more experience than any of us in that camp, plus he’d flown those captured airplanes. So when we’d have an opportunity, he’d sketch in the dirt where everything was, because it was fresh in his mind.”

Hoover and Ennis sat in the revetment for some time making plans. They had already decided that Ennis would be leaving on foot.

“He never wanted to fly again, so he wasn’t going to go with me,” Hoover said.

After a while, a mechanic finally came near the revetment. With a gun in his hands that someone had recently given them for protection in their travels, Hoover motioned for him to enter.

“We couldn’t communicate because he didn’t speak English at all,” Hoover said. “Jerry decided to try his French, and he could speak French. He told him that if he didn’t help me get successfully airborne, he was going to kill him. The fella just turned white. I got in the cockpit. Jerry told him to show me how to start it and help me. He pulled some of the switches because they were all in German and I didn’t know what they were. I got the engine going. The fuel gauge was full and the engine ran up nicely.”

After telling the mechanic to get off the wing, Hoover closed the canopy. Suddenly, he realized that the Germans could start shooting at him as he took off.

“I just opened the throttle full power,” he said. “I didn’t taxi out. I just went straight out across the grass field without going on the taxiway to the runway. I got airborne and pulled the gear up. Then, the stupidity of what I was doing hit me.”

- Bob Hoover (fourth from right, front row) and fellow prisoners held at Stalag 1, near Barth, Germany, during World War II.

- Bob Hoover and German aircraft designer Willy Messerschmitt.

A Calm Voice in the Face of Disaster – Part II