By Di Freeze

Robert A. Hoover, born in 1922, began taking flying lessons when he was 15. After graduating from high school in 1940, the Nashville, Tenn., native, who had by then overcome his nausea at being airborne, by practicing aerobatic maneuvers, joined the Tennessee Air National Guard.

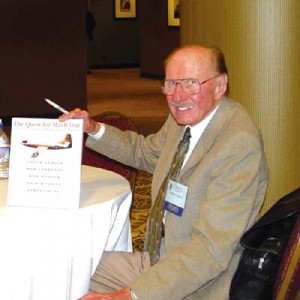

Bob Hoover, holding up a copy of “The Quest for Mach 1,” at the Society of Experimental Test Pilot’s annual symposium, 2003.

Ineligible to go to the Air Corps flying school, because he hadn’t yet turned 21 and didn’t have the requisite two years of college, Hoover trained as a tail-gunner in the 105th Observation Squadron. In September 1940, after the war in Europe broke out, the Tennessee National Guard was called to active duty, and Hoover’s squadron was transferred to Columbia, S.C. While there, his unit was amalgamated into the Army Air Corps.

After the age limit to become a pilot was lowered to 18, Hoover received an assignment for military flight training. He reported for primary training in Helena, Ark., shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and then went on to basic training, at Greenville, Miss., and subsequently to Columbus, Miss., for advanced twin-engine training. Greasing the palm of an impressible technical sergeant manning the personnel office with a 20-dollar bill put the six-foot-two-inch pilot in fighter pilot training, instead of on a path toward transports or bombers.

Hoover soon reported to the 20th Fighter Group, stationed at Drew Field, Tampa, Fla. Shortly after that, Sergeant Hoover was on his way to the European theater, in charge of 67 pilots.

Soon after arriving in Stone, England, in December 1942, Hoover was designated a flight officer. He moved on to Africa in January 1943, to a supply depot in Mediouna, and then tested aircraft such as the P-40, P-39, Spitfire and Hurricane, in Africa and Morocco. He next reported to the Twelfth Air Corps headquarters in Algiers, which was organizing a ferry command, as operations officer. He finally got his wish to enter combat when he had a chance to express that desire to a two-star general.

Nearing his twenty-second birthday, in September 1943, Hoover reported to the 4th Fighter Squadron, 52nd Fighter Group, at Palermo, Sicily, and later, at Calvi, Corsica. On Feb. 9, 1944, the 22-year-old flight leader, flying a Spitfire Mk. Vc, was leading a four-plane-formation of Spitfires patrolling the waters off the Italian and French coasts, when he first shot down a German Focke-Wulf 190, and then was himself shot down by another 190.

Hours later, the pilot who had flown 58 successful missions floated in the water off the coast of Nice, France, until a German corvette picked him up. Wounded, he was now on his way toward the Continental Hotel in Cannes, which was the headquarters for German officers, and then the German Luftwaffe interrogation headquarters, at Oberursel, near Frankfurt, and eventually, toward the Baltic Sea, and Barth, the location of Stalag Luft I.

During the next 15 and a half months, Hoover tried to escape at least 25 times; because of that, he spent a lot of time in solitary confinement. In April 1945, disregarding the orders of Allied Supreme Commander Gen. Dwight Eisenhower to POWs to stay put (he believed the war was nearly over), Hoover and two other POWs took advantage of lax security and made their escape. One of the men, a Canadian airman, soon went his own way. As they continued on, Hoover and Jerry Ennis, also from the 52nd Fighter Group, witnessed the atrocities of Russian soldiers. Eventually, their travels took them to an abandoned Luftwaffe base, just inside the border of Germany, deserted except for a few ground crew.

There, Hoover climbed into the cockpit of a Focke-Wulf 190, which although riddled with bullet holes, looked airworthy. Then he suddenly realized that the Germans could start shooting at him as he took off.

“I just opened the throttle full power,” he said. “I didn’t taxi out. I just went straight out across the grass field without going on the taxiway to the runway. I got airborne and pulled the gear up. Then, the stupidity of what I was doing hit me. I thought, ‘Here I am in a German airplane, no parachute; some second lieutenant right out of flight training could wipe me out in an instant.'”

He was flying a plane with a swastika on the side, so the Allies might take aim as well.

“It happened to be overcast, at about 4,000 feet, I guessed,” he said. “I pulled up to the bottom of that overcast, so I wouldn’t be a target for anybody on the ground or any Americans that didn’t know it was me.”

Hoover headed north until he hit the North Sea.

“I didn’t know where I was; I didn’t have any maps, charts or anything,” he said. “I had decided that when I got to the North Sea, if I turned west, followed the shoreline, I would know I was in safe territory when I saw windmills, because the Dutch people hated the Germans.”

He followed the coastline to the Zuider Zee in Holland, which had been liberated. When he did see the windmills, his fuel gauge was getting low.

“I knew I had to see if one of the fields looked safe enough to land,” he recalled. “I had passed over some airfields that appeared to be deserted. But as the war moved along, we had learned that they would mine the fields, so a deserted field wasn’t somewhere you wanted to land. If they had the runway mined, you’d blow up as soon as you touched down for any distance. I found this field, and circled it maybe once, because the fuel gauge was bouncing off empty. It looked like I could land wheels down, so I did.”

But when he got closer, he spotted a ditch he hadn’t seen from the air.

“I thought, ‘If this thing flips upside down and catches fire, that’s the end,'” he recalled. “I ground-looped it and wiped the landing gear out. The airplane was on its belly. I had wanted to get it back to England; I just thought that would be the greatest thing in the world.”

As darkness approached, he remembered seeing a road on the other side of some trees.

“I thought if I walked to that road maybe I could find somebody, a military vehicle coming along,” he said. “I’d stop them and I’d be okay. Just as I got ready to go into the trees, farmers came at me from all sides. They thought I was a German. Here I am going through one dumb thing after another; here they are, with pitchforks!

“They couldn’t speak English. I kept pointing over on the other side of the forest, and they eventually took me there. We’d no more than gotten up on the road and an English truck came along. I was waving my hands, and he stopped. I said, ‘I’m an American, and they think I’m a German!’ This fella said, ‘Well, you just get in here with us; I don’t think they’ll give you any trouble.'”

Hoover grins and says that later on, everybody made him out to be a hero.

“It was just lousy planning and not being very smart,” he said. “People exaggerated it and made it sound like it was a great escape, but without the guards deserting us, no way. Before then, we never got anybody out of there. We got outside the fence, but they’d be waiting for you. It was impossible until they started deserting.”

According to Hoover, in the last two weeks before the Americans took the camp, on April 30, 1945, about 200 POWs actually got out.

“But General Eisenhower was correct,” he said. “We would’ve been so much safer to stay there. It was actually the dumbest thing I’ve ever done in my life.”

Although he isn’t the only one that escaped from the camp during that period, Hoover says he doesn’t know of anyone else who flew an enemy plane out of the country.

For personal reasons, Hoover didn’t talk about the incident for a long time, even though they did tell the story in his local Nashville paper shortly after the incident. It wasn’t until he was performing at an air show at Redding, Penn., 20 years later, that he talked about it publicly.

“A security person came up to me and said, ‘There’s a man over here that said he was in prison camp with you.’ My narrator said, ‘There must have been a hundred thousand people in that camp with you, because everywhere you go somebody shows up and says they were in the same prison camp with you!'” Hoover recalled.

This time, it was Jerry Ennis.

“He told the story to everybody that was sitting there,” Hoover said. “My announcer said, ‘I’ve known him for all these years and didn’t even know it happened.'”

When his narrator asked if Ennis would be willing to take the microphone and tell the story, he did.

“Once it was told, I tried to tell the truth about it,” Hoover said. “I wasn’t very smart, but without his help, it couldn’t have taken place.”

The journey continues

After hitching that ride, Hoover hooked up with a former fellow POW.

“He had gone over the fence in another direction,” he said. “We were both headed for somewhere near Le Havre, where they had set up camps like Lucky Strike, or some other name like that.”

Once France had been liberated, the U.S. Army established a series of camps just outside of that harbor city, bearing names such as Lucky Strike, Old Gold, Philip Morris, Twenty Grand, and Chesterfield.

“We were skin and bones,” Hoover said. “They’d get you back to your normal weight and give you a thorough physical examination and de-lice you.”

The men hitched rides on military vehicles and trucks, until they reached Le Havre. Hoover said they knew they most likely would be there for three to four weeks, but his companion had a better idea.

“He said, ‘Bob, we got out of that prison camp. I think we can get out of this camp!'” he recalled. “Neither of us wanted to turn ourselves in. We got on a train heading for Paris, because they let the military go for free. We were sitting in a booth with a bunch of gals—Americans who were called Sunshine Girls. They were something like the Red Cross. They had fresh fruit, and we hadn’t been eating well at all. Nelson said, ‘Would you be so kind as to give us an apple? We haven’t eaten one in years.’ They said no. So we moved to another compartment.”

A gentleman—who did share his fruit with them, as well as a plan—occupied that compartment.

“He’d just gotten off a ship,” Hoover said. “He’d been in the flight school training I was in and washed out, and went to the Merchant Marines. He asked us how long we planned on being in Paris, and I told him I hoped long enough to get some clothes and some money. He said, ‘If you’ll meet me at the railroad station where we get off, I’ll take you with me back to La Havre, and I’ll smuggle you on board the ship I’m on; we’re heading for the U.S.'”

They would later find out that, without his knowledge, orders had been changed.

“He smuggled us on, and we were going to England!” Hoover said. “We thought we were going home. He put us in nice accommodations on the ship.”

Their new friend worked out a code, and told them if anyone knocked, not to answer for anyone but him. He also left them with plenty of food, but Hoover’s companion was antsy.

“Nelson just couldn’t sit still,” he said. “He unwisely went to the place, like a commissary, where you buy candy bars and cigarettes and stuff like that. You had to have a coupon to be able to get anything.”

When he was asked for his coupon, and responded that he didn’t have one, an Army captain standing behind him, who was also an intelligence officer, overheard the exchange.

“He followed him back to the room,” Hoover said. “When Nelson opened the door, he walked right in behind him. He said, ‘I want to interrogate you two.’ Here we are in these old raggedy clothes. We told him we were prisoners of war and we were trying to get home; we thought the ship was going to the U.S. He said, ‘I don’t believe you; I think you’re German spies.’ I said, ‘Would a German spy talk like I do?’ He said, ‘They’ll disguise themselves in anyway possible.'”

He left, but a few minutes later, military policemen and the captain were at the door. After being told they were under arrest, Hoover and the other former POW were taken to the lowest deck they had on the ship, now serving as the brig.

“The third mate, who had gotten us smuggled aboard, learned very quickly what had happened,” Hoover said. “He came to the cell and said, ‘I have some old stevedore clothes I’m going to bring you. I’m going to figure out a way to get that cell unlocked. You get in these clothes and I’ll have bags for you to carry down to the truck down at the gangplank. Next to the truck will be a small car; the person in that car, a friend of ours, is going to drive you wherever you want to go in London.’ By golly! We picked up these bags and went right down that gangplank, right into that car.”

Later, Hoover’s traveling partner got in touch with a wealthy and titled family friend, who gave them money for uniforms, and anything else they might need.

“We lived pretty high on the hog,” Hoover said. “We stayed at some real nice places.”

While he was in England, Hoover went to visit his brother Leroy.

“One of the reasons I went to Paris earlier was that I thought he was stationed there,” Hoover said. “I found out through somebody in the military where he was located in England.”

At that time, Hoover found out their mother was gravely ill.

Members of the X-1 team, responsible for the breaking of the sound barrier in 1947, included flight engineer Ed Swindell, backup pilot Bob Hoover, B-29 pilot Bob Cardinas, X-1 pilot Chuck Yeager, Bell engineer Dick Frost and Air Force engineer Jack Ridley

“I went back to Nelson and told him I was going to turn myself in, because I had to get home,” Hoover said. “He said, ‘I’ll go with you. We got on the boat, and guess what? It was the same boat we had taken from Le Havre to England. They treated us royally all the way back. We had a first-class cabin. There was a bunch of nurses on board—Heaven without dying!”

By the time Hoover caught that ship for New York, he had spent nearly two and a half years overseas.

Back in the U.S.

Upon reaching the U.S., Hoover was sent to San Antonio, Texas, where he was debriefed and given several physical exams. Then, he took a train back to Nashville. It wasn’t long before Col. Marvin McNickle, his former commanding officer in Corsica, now assigned to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, called with a hopeful message.

Knowing Hoover wanted to be assigned to Wright Field, he said he thought he had secured an assignment for him, which wasn’t an easy task. Although Hoover’s experience with testing aircraft overseas would be a plus, he didn’t have the educational background or engineering knowledge necessary. Still, McNickle wrote Gen. Fred Dent, the commander at Wright-Patterson, asking him to give Hoover a chance.

“He was absolutely wonderful,” Hoover said. “I immediately got an enrollment to the test pilot school. Sometimes you’d sit around at Wright Field for six months or a year before you could get a slot. He was always there to help me if I got into trouble.”

Hoover’s first assignment in the Flight Test Division at Wright Field was to perform compressibility tests on the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, as well as captured German and Japanese aircraft. However, it wasn’t long before Hoover called on McNickle for assistance. Gus Lundquist, the fellow POW at Stalag I who had familiarized Hoover with the FW-190, had returned to his pre-war job at Wright Field as a test pilot. One day, in the summer of 1945, the two men got into an intense, and forbidden, dogfight near the field.

Wright Field had the only jets in the Army Air Corps fleet. On that day, Lindquist was flying one of those jets, a Bell P-59; Hoover was flying a Lockheed P-38 prop fighter. Neither knew that their commanding officer, Lt. Col. Bill Counsel, was watching.

When the men landed, the no-nonsense CO called them to his office and told them they were being reassigned to fly B-17 bombers in Florida.

“That assignment was the bottom rung for a test pilot,” Hoover said.

Lindquist quit the program without an argument, but Hoover went to Counsel’s base quarters later to plead for mercy. Although Counsel appeared unmoved by the impassioned plea, his wife convinced him to give Hoover another chance.

Although grounded, Hoover remained at Wright Field, as a clerk. He stayed behind a typewriter until Col. Albert Boyd, who assumed command of the Flight Test Division in October 1945, replaced Counsel.

When the chief of fighter flight test recommended that Hoover check out Boyd after his arrival at Wright Field, it led to questions as to why he was a clerk typist. Satisfied that Hoover had been grounded long enough, Boyd soon released him from typing up operational orders.

That wouldn’t be the last time Hoover would be grounded. The next time, it was Boyd clipping his wings. In that case, it had to do with a harrowing flight in the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, the first operational U.S. jet fighter, and a test of wills.

Hoover’s tribulations with the P-80 included a flight in September 1946 he made to Beverly, Mass., in which the jet turbines failed at 42,000 feet, forcing him to cut the engine. Without an ejection seat or a working oxygen supply, Hoover had to decide whether to ditch the plane and parachute over the side or somehow try to stretch the glide and land at a military base.

Ready to bail out at 7,500 feet, he realized he was close to an airfield (Westover Airfield, Chicopee, Mass.), hit the switch, and was relieved when the P-80 started. With fore and aft fire-warning lights illuminated, the 24-year-old first lieutenant finally landed. He ended up in the hospital for four days recovering from hypothermia and frostbite.

“The P-80’s skin was burned off all the way from the engine back to the tail,” Hoover said.

Hoover also worked on a project with a test P-80 that would be the first jet to be powered by gasoline. Prior to that, the Army Air Corps had always used either jet fuel or kerosene in jet aircraft. Hoover said that when they got the jets they couldn’t fuel them, because the two options weren’t available at bases across the country.

Because of lead deposits, and since gasoline has a lower flash point than kerosene, making it more combustible, it was unknown if the jets faced a fire hazard. Initially, an engine powered by gasoline was set up on a test stand. When that was successful, the engine was installed in the test aircraft.

“They took the tail off the airplane so the backend would be exposed,” Hoover said. “They took the canopy off the airplane and they put fire trucks all the away around it, except for behind it. I had to sit in the cockpit hour after hour, before they finally felt it was safe. The first few hours I was worrying about the thing blowing up, with all those fire trucks there, but everything checked out fine.”

Shortly after that, with no other jets available except for Hoover’s test plane, Boyd asked him to perform aerobatic maneuvers in the P-80 for Mediterranean Theater Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Joseph McNarney.

“All of the test pilots were going to fly some kind of a different airplane, and the general would see all of them fly by,” Hoover said.

Everything went well during the first part of Hoover’s flight, but at 10,000 feet, the engine flamed out. As he tried to come in for a landing, the landing gear wouldn’t lock down. A small side-stick that provided a manual auxiliary pump for the hydraulics, permitting the wheels to extend when pumped, wouldn’t work, no matter how hard he pumped the stick.

“I knew I couldn’t make the runway with the altitude and airspeed available, and I had to come up over the highway to get to it,” he said. “There were cars parked all along the highway. I thought, ‘I’d better just dive straight in and kill myself.’ At the last minute, I decided I could get a wing between two cars. My main wheel crunched the hood of one of them; that’s all the damage it did to the car. When I rolled out, the runway was about 30 feet below the road.”

But Hoover never made it to the runway.

“It stalled out,” he said. “I just didn’t have any air speed left.”

Hoover was fine, but the aircraft had suffered damage.

“The impact with the ground forced the landing-gear struts through the wings and broke the fuselage back of the cockpit,” he said. “The nose was broken.”

The impact had also jammed the normal and emergency canopy release mechanisms.

“Of course, I’m worried about fire,” Hoover said. “The fuel tank had ruptured, but there was no heat. The engine was cold.”

After releasing his safety harness, Hoover repeatedly tried to press his shoulders and back against the canopy to force it off.

“I was trying desperately to get out of the airplane,” he said, simulating his actions that day. “I wasn’t able to force the canopy up, because it was twisted.”

Hoover was relieved when he heard rescue teams approaching.

“They asked me if I was hurt, and I said, ‘No, but my back is bothering me.’ They took me over and X-rayed me, but there was nothing wrong,” he recalled. “I just strained all the muscles in my back. They gave me a clean bill of health.”

His relationship with Boyd would be strained as well that afternoon, when they argued over his ability to complete a project.

“They had ramjet engines on the wingtips of a P-51,” he said. “I was the project pilot on this other program as well. I was sitting in the cockpit ready to go, and the engineers were there with me, telling me what I needed to do, when Boyd drove up the ramp in his staff car.”

When Boyd saw him in the cockpit, he stopped.

“He came over and said, ‘Young man, you just had a hairy experience. I want you to take some time off.’ I said, ‘Colonel, I’m not hurt! I’m only hurting because I lost an airplane. This is the last flight we have to make on the project, and I can finish it. Engineering is eager to get this data,'” Hoover recalled.

When the colonel repeated his command that he get out of the cockpit, Hoover asked Boyd to give him one good reason why he shouldn’t fly the plane.

“He got mad,” Hoover said. “He said, ‘You’re grounded.’ I said, ‘Yes, Sir.’ I goofed. If I had been Al Boyd, I would’ve court-martialed me. I insulted him—in front of other people.”

After Hoover had been grounded for nearly two weeks, McNickle, who was head of one of the labs that owned the airplanes, called Boyd and told him that although he had good reason to get rid of Hoover, he was a superb pilot, and he wanted him to test his lab’s aircraft.

“Boyd had no choice,” Hoover said. “Marvin called the general above Boyd first, and told him what he was going to do. The general said, ‘Well, you work it out, and if you can’t, come back to me.’ Boyd finally accepted, reluctantly, but he was watching me like a hawk, just trying to find something to criticize.”

Hoover received a temporary assignment flying test aircraft for McNickle’s lab, until Boyd relented and put him back in the flight-test program.

The need for speed

In 1946, besides evaluating and testing the Heinkel 162, a German jet fighter, Hoover was assigned to a program involving the Messerschmitt 163 Komet. The German rocket plane had reached nearly 600 miles per hour, after World War II.

“It was faster than anything we had in our country, and we wanted to learn as much as we could about their technology,” Hoover said.

Lundquist had performed the glide flights before leaving the program, and Hoover was to make the first rocket-powered flight, but that flight was cancelled.

“They had it up to .92 Mach number before hitting compressibility,” he said. “When we got ready to do the powered part of the flying with a rocket motor, everybody in the power plant division decided the volatility of the fuel and the kind of losses that Germany had suffered wasn’t worth the risk. When they canceled my flight, they probably did me a favor.”

By 1946, several aviators had died trying to fly faster than Mach 1, or the speed of sound, including Geoffrey De Havilland Jr., a British pilot who attempted to pass through the “sound barrier” in the Sparrow. It was beginning to look like Hoover would get a chance to attempt the feat as well.

America and the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (forerunner to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration) were pinning their hopes on the Bell Aircraft Company’s X-1, a bright orange, $6 million rocket-propelled craft, with 6,000 pounds of thrust, which had to be dropped from the belly of a B-29 mother ship, at 25,000 feet. Then, without fuel, it would glide back and land on the lakebed. A civilian test pilot, Chalmers “Slick” Goodlin, had made over 20 flights in the aircraft, eventually taking it to .8 Mach.

A big concern was whether the structural integrity of the X-1 could withstand the extreme stress loads likely to be encountered at Mach 1. Although it was considered a highly dangerous test flight, Bell, and the military, balked at Goodlin’s $150,000 demand—if he successfully exceeded Mach 1. That led to a search for a qualified military pilot, in May 1947.

“Until the news broke at Wright Field that they were looking for a volunteer to break the sound barrier, none of the test pilots there knew much about it,” Hoover recalled.

He was among several pilots who signed up for the mission. After he had been interviewed several times, Counsel told him he was his choice, and to start preparing.

“I did my first centrifuge rides,” Hoover said. “That was before Colonel Boyd took over the flight test division.”

But the first lieutenant soon discovered that sometimes it takes a while for consequences from actions to catch up with you. One day, Boyd called Hoover to his office, to inquire about an incident that had occurred months earlier.

Bob Hoover and German fighter pilot ace Eric Hartman, In World War II, Hartman shot down 352 Allied planes.

“A friend who had family and friends in Springfield, Ohio, asked me to buzz the Springfield Airport,” Hoover said. “He was going to say that he was flying the P-80, but he wasn’t checked out in jets. I said whenever I came back from a test flight with enough fuel to do it, I would. One day I had enough fuel and I buzzed it—upside down. The numbers were so small back in those days that you couldn’t have read it anyway, especially if you were upside down.”

When Hoover admitted to the deed, Boyd said, “Well, I know one thing about you. You’re honest.'”

Then, Boyd told him how they knew it was him. Only one jet had been flying in the U.S. on that day, and a Civil Aeronautics Administration official had witnessed his two inverted flybys and filed a “safety violation” report. After telling him that, Boyd said there was a second thing he knew about him.

“You can also be irresponsible,” he said. “I’m pulling you off the number one slot on the X-1 program.”

Hoover was absolutely devastated. One reason, he said, was that it wasn’t often that you got the chance to be the “first” to do something. The second, and maybe even worse, was that he was now going to have to back up someone else.

“I didn’t respect the people that were in this pyramid to get to the top,” he said. “I thought, ‘If I have to back up someone whose skills I don’t have any appreciation for, the next several months are going to be miserable.'”

Weeks went by before Boyd told Hoover he had selected a 24-year-old captain named Chuck Yeager, and asked if he knew him.

“I could hardly keep a smile off my face,” Hoover said, with undoubtedly the same smile on his face. “I said, ‘He’s the greatest aviator I’ve ever known; you couldn’t have made a better decision.’ I came out of his office a happy person, after being down in the dumps for so long.”

Decades later, Hoover still says Yeager is “the best.”

“I respect and admire him,” he said. “We have a wonderful friendship. We were already good friends before that. We were fighting buddies in the air. He was the only person I had ever encountered that I couldn’t ‘shoot down.'”

Hoover recalled that the first time they “hassled” was from altitude down to the deck. Hoover, who had arrived at Wright Field about the same time as his new and worthy opponent, was flying a P-38 prop fighter, and Yeager, a maintenance officer, was flying a Bell P-59 jet, over Wright Field, in early fall 1945.

Yeager would later recall that sometime during the dogfight, he whipped the jet around, pulled straight up into a vertical climb—and then stalled while going straight up.

“I started spinning down and that damn P-38 was spinning up, both airplanes out of control,” he said.

They went by each other less than 10 feet apart, before it was decided to break it off, while they were both still alive. Yeager landed shortly after Hoover did, parking next to him.

“He says, ‘You could sure fly the hell out of that airplane,'” Hoover reminisced. “I said, ‘Well, look who’s talking! I’ve never met anybody as skilled as you.’ At that point, we became good friends.”

Number 2

Hoover said that his and Yeager’s selection to the program was a cause of debate. Some said since they were both among the most junior pilots in the flight test section at Wright, they were chosen because they were the most expendable.

“I think the rumor may have been right,” Hoover grinned. “We were both young pilots, only 24.”

He added that if things went wrong, their inexperience could be blamed. Since Hoover would take over if Yeager became ill or incapacitated, he was present in all the meetings with Yeager, Jack Ridley, who was the flight engineer assigned to the program, and a handful of others on the program.

“I think I was prepared to go as much as anyone could be,” Hoover said. “People jokingly said I was keeping my finger crossed, but our friendship was stronger than that.”

Yeager and Hoover had been close before, but they were now inseparable. Both were involved in several experiments NACA’s medical team felt necessary.

“Chuck and I had some real severe centrifuge testing to establish how much we could handle,” Hoover said. “The airplane was good for 18 positive g’s. That’s a lot more than we could handle physically.”

Wearing capstan pressure suits that looked like “something a primitive deep-sea diver would wear,” manufactured by the David Clark Company of Worchester, Mass.—at the time manufacturing bras and girdles—the men were locked in altitude test chambers and strapped to various centrifuges. The equipment exposed them to high g’s to determine their level of tolerance before blackout and unconsciousness. On one occasion, the chamber technician forgot to open the valve on Hoover’s oxygen supply.

“I can’t express the helpless feeling of having your lungs locked in the middle of a breath unable to inhale or exhale,” he said. “I almost choked to death; I was turning purple. If Chuck hadn’t looked through the porthole window at that particular instant, I would’ve been asphyxiated.”

Muroc

Tests on the X-1 began at Muroc, Calif., chosen because of its isolation and miles of dry lakebed, perfect for landing, in late July 1947. There, Walt Williams headed the NACA team, in charge of the monitoring instrumentation aboard the X-1. The team was instrumental in determining the pace at which the program progressed.

“He wasn’t all that thrilled to be working with us,” Hoover said. “He and the other NACA officials made life difficult for us.”

Hoover said Muroc, consisting of modest World War II barracks, a Spartan headquarters building and two hangars, resembled an old Western ghost town. A general store near the base offered necessities and Pancho Barnes’ Fly-Inn Bar and Restaurant, later to be known as the Happy Bottom Riding Club, provided a place to wind down. Ironically, the hotspot at the edge of Rogers Dry Lake was also a constant reminder of the dangers test pilots faced; photos of pilots who had died hung on the wall behind the bar.

“Fatality rates were extremely high in those days,” Hoover said.

The first non-powered flights were in August. During those flights, after being dropped at 25,000 feet, Hoover would glide back and land on the lakebed. During the first glide flight, Dick Frost, Bell’s X-1 project engineer, flew low chase, while Hoover flew high chase (above 40,000). As Yeager, dangling from the B-29 over the Mojave Desert, waited for Maj. Bob Cardenas, piloting the B-29, to drop him, he went over his checklist. Hoover, in the P-80, took the opportunity to buzz him.

“He flew by so close, he almost knocked me loose from the B-29,” Yeager said, adding that the X-1 jumped three feet in the air.

“Bastard!” hollered Yeager, and then told Hoover that if his aircraft was armed, he’d shoot him out of the sky.

Yeager didn’t respond to Hoover’s challenge to “come and get me,” that time.

“My second glide flight, Hoover about shook me out of the airplane again,” Yeager said. “Cardenas cussed and then I cussed. On the third glide flight—my last one—when I dropped out of the B-29, Hoover had already buzzed us, and turned back in, so I turned back in to him.”

Their dogfight, down to the deck, resulted in Yeager almost stalling the X-1.

During his first powered flight, on the last day in August, Yeager reached .7 Mach, before diving for Muroc, and reaching .8 Mach, a dive-glide faster than most jets at full power.

On October 5, his sixth powered flight, at .86 Mach, he experienced shock-wave buffeting for the first time. The analysis of the telemetry after his seventh flight, on which he reached .94 Mach and lost elevator effectiveness (due to the loss of pitch control), revealed that a shock wave formed on the horizontal stabilizer at about .88 Mach.

As speed increased to about .94, the wave “lay down,” moving back on the horizontal stabilizer until it was at the elevator’s hinge point, resulting in the loss of the elevator’s effectiveness, and control of the X-1. The problem was solved when Ridley suggested using only the horizontal stabilizer. Because they had anticipated elevator ineffectiveness caused by shock waves, Bell’s engineers had built an extra control authority, a trim switch in the cockpit, into the stabilizer. This allowed a small air motor to pivot the stabilizer up or down, creating a “moving tail” that could act as an auxiliary elevator by lowering or raising the airplane’s nose.

With the belief that Yeager had gone up to .955 Mach on the following flight, the NACA team suggested a speed of .97 Mach for the next mission. However, what wasn’t known until the flight data was reduced several days later was that he had officially flown .988 Mach while testing the stabilizer, and, Yeager said, there was a possibility he had already attained supersonic speed.

A few days later, history “might” have changed. That Sunday, following dinner at Pancho’s, Chuck and Glennis Yeager relaxed on a midnight horse ride. While racing back in the moonless night, Yeager was unable to see that someone had closed the gate until the last moment, and then tried to veer his horse to miss it. It was too late; he hit the gate and tumbled through the air, cracking two ribs.

Yeager kept the accident a secret to all but those closest to him, and the local doctor who taped him up, to avoid grounding. The next afternoon, he drove to the base, knowing that since he didn’t have to move his hands at critical moments, he could fly with broken ribs; the X-1’s H-shaped control wheel was where the rocket thrusters and key instrumentation switches were located. Still, he needed to lock the cockpit door, which required considerable strength. Ridley suggested a 10-inch piece of broomstick to lift and lock the door handle, and it worked.

On Oct. 14, 1947, Hoover was again flying high chase, when Yeager broke the sound barrier.

“Boy, he was whistling,” Hoover recalled. “He went by me as if I was standing still. He said on the radio to Jack, ‘You’re going to have to get this Machmeter fixed. It just jumped, and then it went off the scale.’ As soon as Chuck said that, we all knew he had broken the sound barrier. I hadn’t heard it, but those on the ground heard what they said sounded like thunder in the distance.”

When Yeager broke the sound barrier, traveling at more than 700 mph (1.07 Mach), Hoover took the first photographs of the diamond-shaped shock waves from the exhaust plume behind the X-1.

As for the knowledge that Yeager’s accident could’ve resulted in him making that flight, Hoover says he didn’t encourage him “not” to take the flight.

“I wanted to, but only because I was worried he couldn’t handle it,” he said. “I think he was so motivated to get there because this was ‘the big flight.’ He did a beautiful job.”

Hoover said that was a wonderful day for both of them.

“On our way down, I got back on his wing again,” he said. I said, ‘Pard, you got a steak dinner coming tonight at Pancho’s. She had told us that whoever got there first, she was buying steak dinners for that crew.”

Although the celebrating began, it didn’t last long.

“Somebody came in just as we were having a little fun and said, ‘This is top secret—classified,'” Hoover recalled. “I said, ‘It’s too late! We’ve already been talking about it.’ They said, ‘From now on, don’t open your mouth.’ Of course, by then, the horse was out of the barn.”

Another disappointment

One of the great disappointments in Hoover’s life was that he never flew the X-1. Before he had a chance to, he suffered serious injuries on another project involving the F-84 Thunderjet. The incident happened barely a month after Yeager’s historic flight, when the F-84’s engine caught fire over the Antelope Valley.

“The test called for doing what in flight test vernacular is ‘speed power,’ at different altitudes,” Hoover said. “I was at about 40,000 feet. In those days, we had no pressurization. I was all iced up; you couldn’t see out. No pressurization; no heat. When it quit, the first thing that happened was the fire warning lights came on. When they both come on, you know you better be ready to go, because it could blow up any minute.”

When the lights came on, he prepared to eject.

“I was sitting on the first ejection seat we had in this country. There was an ejection seat in one of the German airplanes I evaluated and we copied it to make this seat,” he explained.

Hoover called in a mayday, and prepared to bail out. When he noticed the fire warning lights had gone out, he thought, “I’m safe.” He would later find out the reason the aircraft was diving out of control; the intensity of the fire had burned away the push-pull rods to the flight controls.

Knowing the aircraft would be in a steep dive and traveling at a high speed when he bailed out, Hoover pulled the “next of kin” handles on the ejection seat, but nothing happened. Quickly, he unfastened his safety harness and oxygen hose, and jettisoned the canopy.

“I was sucked out, because I had already unfastened everything,” he said. “I went right into the tail. I hit on the back of my legs underneath my knees.”

The rubber oxygen mask he still had on gave his face a little protection when it hit his knees.

“It knocked out a couple of teeth and busted up my jaw, but I didn’t feel that until later,” he said.

Although the blow to his head stunned him, as he was free falling, the rush of air revived him, and he pulled the ripcord on his parachute.

“When I came to, I was looking around, and I thought, ‘I have to get on the ground quickly. I’m dying,'” he recalled. “I looked down and my legs were just dangling. I tried to spill the parachute and not lose my strength. It opened up again. It was an eternity to get to the ground. Finally, when I did, the wind had picked up to about 30 miles an hour.”

Although he was worried about how bad it would hurt to land on two broken legs, Hoover said he learned that once you hit the threshold of pain, it doesn’t get any worse.

“I landed crumpled up on the ground,” he said. “The wind kept the parachute inflated. It was dragging me across the desert through sagebrush. I tried to pull the clamps, but it was too much force for me.

- Gen. James Doolittle and former U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater present Bob Hoover with an Air Force Association award.

- Bob and Colleen Hoover with Charles Lindbergh, the first man to fly across the Atlantic, and Neil Armstrong, the first man to land on the moon. This photo was taken shortly after Armstrong returned from space.

- Avid aviator and hotel tycoon Barron Hilton with Bob Hoover.

A Calm Voice in the Face of Disaster – Finale.