Bob Hoover spends time with Bea Khan Wilhite, Colorado Aviation Historical Society president, and CAHF honoree Carl Williams, a cable pioneer who has a passion for aviation.

By Bill Stansbeary

The Colorado Aviation Historical Society held their 37th annual Colorado Aviation Hall of Fame banquet on Nov. 3 at the Lakewood Country Club. Aviation legend R.A. “Bob” Hoover was guest speaker.

Jerry Lips provided the introduction for Hoover, who was presented with Airport Journals’ Freedom of Flight award during the 2007 Living Legends of Aviation event earlier this year.

Hoover, considered by his peers as a “pilot’s pilot,” has served America in war and peace, as a fighter pilot, test pilot and master of aerobatics. His military awards include the Distinguished Flying Cross, Soldier’s Medal for Valor, Purple Heart and French Croix de Guerre. An inductee of the National Aviation Hall of Fame and the International Council of Air Shows Hall of Fame, he’s received many civilian awards, including the Lindbergh Medal and Bill Barber Award for Showmanship. His contributions to aviation include two terms as president of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots.

Born in Nashville, Tenn., in 1922, Hoover was old enough to be fascinated when Charles Lindbergh made his historic transatlantic flight in 1927. His love for aviation grew, resulting in flying lessons at age 15.

Jerry and Laurie Lips visit with Bob Hoover, honored by Airport Journals with the Freedom of Flight award earlier this year.

He joined the Tennessee Air National Guard on his 18th birthday, and went on active duty with the unit in September 1940. After asking for an assignment for military flight training, he began primary training in December 1941, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

He arrived in England in December 1942, as part of the 20th Fighter Group, where he was given the rank of designated flight officer. He moved on to North Africa, before reporting to the 12th Air Corps headquarters in Algiers, and then joining the 4th Fighter Squadron, 52nd Fighter Group in September 1943, soon to be located in Corsica, France.

On Feb. 9, 1944, while heading a four-plane-formation of Spitfires on a mission to patrol the waters off the Italian and French coasts, Hoover was shot down. Hours later, a German corvette picked up the wounded pilot as he floated in the water off the coast of Nice, France.

Hoover would eventually be taken to Stalag Luft 1 in Barth. He made many attempts to escape, before fleeing in the early spring of 1945. He ended up at an abandoned Luftwaffe air base just inside Germany’s border, where he discovered an airworthy Focke-Wulf 190, which he flew to Holland.

I-Jet co-founder Lynn Krogh (left), who provided transportation to get Bob Hoover from California to Colorado, and Bea Khan Wilhite point out the motto of the Colorado Aviation Historical Society, “Balloons to Ballistics.”

Hoover was later assigned to the Flight Test Division at Wright Field. He flew the chase plane for Chuck Yeager’s historic flight in the Bell X-1 on Oct. 14, 1947, to break the sound barrier, flying at a speed of 700 mph (1.07 Mach). From his chase plane, he took the very first photographs of the diamond-shaped shock waves from the exhaust plume behind the X-1 rocket ship. Those pictures were on President Harry Truman’s desk the next day.

During the banquet, Hoover spoke about one of his greatest disappointments: he never got the chance to fly the X-1 because of a serious accident that broke both of his legs, just a month after the breakthrough flight at Muroc Air Force Base (now Edwards AFB) in California.

Hoover recalled that he got into trouble when the jet engine of the F-84 Thunderjet he was flying failed and caught on fire high over the Antelope Valley. He called “mayday,” giving his location while diving out of control because the linkage to the flight controls had burned away. He pulled the “next-of-kin handles” on the ejection seat while in a steep dive at high speed, but they didn’t fire the seat. Quickly, he unfastened the safety harness and oxygen hose and then jettisoned the canopy. After being sucked out of the cockpit, his body slammed into the aircraft tail with tremendous force on the back of his knees.

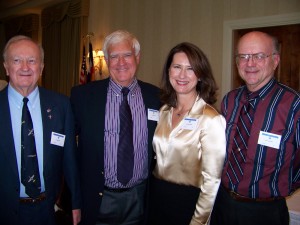

L to R: Attendees who were riveted by Bob Hoover’s story included Mike Bertz, Joe Thibodeau, Julie Blankenship and Allan Lockheed.

He floated to the ground miles away from the burning plane wreckage. A ranch hand in an old pickup truck finally located Hoover, suffering from two broken legs and multiple facial injuries, and drove him to the Antelope Valley Hospital. However, the civilian staff couldn’t treat him, so they called officials at Muroc, who sent an ambulance to bring him to the small hospital at the base.

After six weeks of rehabilitation, Hoover received clearance to get back in the cockpit, but by that time, another pilot in the X-1 program had replaced him.

Hoover left the military in December 1948, and joined General Motor’s Allison Division as a test pilot. Three years later, he left to work for North American Aviation, located at Los Angeles International Airport. He remained with the company for 36 years.

In the mid-1950s, Hoover began flying North American Aviation’s civil and military aircraft at air shows. In the early 1960s, he helped Bill Stead set up the Reno National Championship Air Races and Air Show. He served as the first official starter in 1964, in a P-51 Mustang, and continued that role for more than three decades.

In 1973, he began flying aerobatic demonstrations in a Shrike Commander 500S (N500RA). Ten years later, he began flying both the P-51 and the Shrike for demonstrations.

Over the years, audiences particularly enjoyed his signature “Dead Engine Energy Management Maneuver.” Performing from 3,500 feet above the ground, Hoover would dive the plane, with both engines shut off and propellers feathered, and then pull the nose up into a loop and complete an eight-point hesitation slow roll. Upon recovery, he’d maneuver the plane through a 180-degree turn before heading toward the runway. He ended by landing one wheel at a time.

In April 2000, Hoover flew his famous Shrike to Sun ‘n Fun, and then donated the plane to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. The Smithsonian’s Stephen F. Udvar-Hazy Center was still under construction, so the plane was loaned to the International Sport Aviation Museum in Lakeland, Fla. On Oct. 10, 2003, he flew the aircraft to Washington Dulles International Airport, in preparation for the center’s December 2003 grand opening.

Bill Bower, one of 11 remaining flight crewmembers from the Doolittle Raid over Tokyo, Japan during World War II, meets with Bob Hoover, who was a good friend of Gen. James “Jimmy” Doolittle.

The experiences he talked about during the event, as well as many others are included in his autobiography, “Forever Flying.” Hoover will also be one of the featured legends in “Living Legends of Aviation,” a compilation of biographies by Airport Journals editor Di Freeze.

Bob Hoover gets to know Allan Lockheed Jr. (left) and Emily Howell Warner, who helped open cockpits to all women when she successfully petitioned Frontier to hire her as a pilot in 1973.