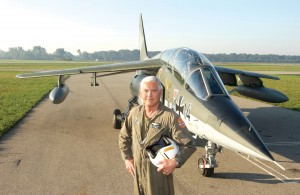

Bob Lutz said the Alpha Jet is a demanding airplane that requires a heightened state of awareness of the angle of attack at all times.

Bob Lutz, vice chairman of global product development at General Motors Corporation, says that throughout his career in the auto industry he’s been called a “car guy.” He said it hasn’t always been a positive label, but he at least came by it “honestly.” He adds that he’s never ceased to be amazed at the number of highly placed people in the auto industry who aren’t “car guys.”

Although he’s pleased with that label, there are others that are just as fitting; he’s definitely a “plane guy” as well. Evidence of both classifications can be found in his GM office, which is filled with car and airplane models.

The former Marine captain and jet attack pilot, who is also the author of “Guts: 8 Laws of Business from One of the Most Innovative Business Leaders of our Time,” a popular business management book, says he’s “never fit into the standard mold too well.” He not only flies a helicopter to work, but also gets as many hours as he can in his Czech-built Aero Vodochody L-39 “Albatros” and his West German Dornier A model Alpha Jet.

“Some people like golf and I like this,” he said.

He affirmed that he bought the L-39 jet trainer, a single-engine, two-seater, subsonic aircraft, because he missed the “adrenaline rush” of military flying.

“I’ve always longed for the experience of flying a single-engine tactical military jet,” Lutz said. “I used to dream about it at night. Whenever I saw an F-18 or an F-16, I had this thought of powerful nostalgia—and then this sinking feeling, the realization that I would never, ever experience that again.”

His dreams turned into reality, however, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when L-39 jet trainers, built as the successor to Czechoslovakia’s earlier trainer, the L-29 “Delfin,” suddenly came on the market.

“I saw an ad in Trade-a-Plane that International Jets had put in,” Lutz recalled. “It had a picture of an L-39 and it said, ‘Five in stock.’ Two were already crossed off with red Xs, saying, ‘Sold!’ I thought, ‘Whoa, I’d better hurry!’ I told my wife, ‘Look at this!’ She said, ‘Well, you know, if not you, who? And if not now, when?” So, we went down and got it.”

The L-39 kept him contented until last year, when he decided to vary his recreational flying a little and bought the Alpha Jet, a jet fighter. Lutz estimates that between the L-39, the Alpha Jet and his helicopter, he’ll probably be averaging about 180 hours a year.

“Before, I was getting about 100 odd hours in the L-39,” he said. I don’t think it can be possible to fly twice as much. It will probably be 80 hours in the helicopter, 50 in the L-39 and 50 in the Alpha Jet.”

Where the dream began

Robert A. Lutz enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps after a period of youthful restlessness and rebellion. Born in Zurich, Switzerland, on Feb. 12, 1932, he had crossed the Atlantic five times before he was 8 years old, due to his father’s business, and held both Swiss and U.S. citizenship by age 11. His father, a Swiss banker, was continually transferred back and forth between Zurich and Wall Street by his bank, Credit Suisse.

The reoccurring upheaval resulted in Lutz often getting behind his Swiss counterparts and being held back in school. His education suffered a further setback after his family finally settled down in the Zurich area following World War II, and he was booted out of the prestigious boarding school he was attending for his high school years.

Although the official reason was “academic and disciplinary problems,” Lutz said the real problem was he was more interested in romance than studying. His father’s solution was six months of manual labor in a leather warehouse. He also extracted a promise from his son that in exchange for one more chance at education, at a public school in Lausanne, Switzerland, he would enlist in the U.S. Marine Corps.

After 22-year-old Bob Lutz finally got his high school diploma, he made good on his promise to his dad. He didn’t even consider rebelling against that wish, since he had always had an admiration for the Corps, and because of an earlier desire to be a military pilot.

As a youngster in the waning days of WWII, he sketched fighter planes in his school notebook and dreamed of being an ace and flying a P-51 Mustang or a Chance Vought F4U Corsair. His heroes included Joe Foss and Pappy Boyington.

Lutz began his decade of service in the U.S. Marine Corp in 1954, after the cessation of hostilities in Korea. At boot camp at Parris Island, S.C., he said he acquired a sense of discipline that tempered his previous “unbridled bent.”

“It’s a form of brainwashing,” he said. “They deprogram the civilian and create an entirely new ethic and outlook for you.”

Lutz entered the Naval Aviation Cadet Program (NAVCAD), which was then open to promising enlisted men from the Navy or the Marine Corps, as well as civilians. He received his Wings of Gold as a Marine aviator in 1956, and served on active duty until 1959.

The first aircraft Lutz flew during U.S. Navy flight training was the North American SNJ-4.

“I have about 125 hours in SNJs,” he said. “It’s a very interesting aircraft to fly—certainly not easy. It was, as you know, in WWII, considered an advanced trainer, and yet after WWII, it became a primary trainer. It was quite a challenging aircraft.”

Lutz, who has about 2,500 hours in military aircraft from that period, said the popular trainer was the last propeller-driven aircraft he ever flew. In flight training, after the SNJ, Lutz flew the Lockheed TV-2 (T-33) and the Grumman F9F-5 Panther. Once out of flight training, he flew aircraft including the McDonnell Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and the McDonnell F2H Banshee.

“I also flew the Grumman F9F-8 Cougar with swept wings,” he said.

The aircraft he unquestionably enjoyed flying the most was the Douglas A-4.

Bob Lutz boards a GM corporate jet at the GMATS terminal at Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport.

“It was the highest performance,” he said. “It was a very simple and incredibly agile aircraft. It was just wonderful the way that thing could yank and bank, and when it was flying, it would climb like crazy.”

Trained to be a conventional or nuclear weapons attack pilot, Lutz served in Korea for a time as the air liaison officer of the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marines, based on Okinawa. Following his tour in the Far East, he returned to northern California, the site of one of his earlier assignments, to become a Reserve aviator.

Lutz was intent on making the military his career, but needed a college degree to advance as an officer. So, while flying in the reserve out of the Alameda Naval Air Station, he entered the University of California at Berkeley.

Although he served as a jet-attack aviator until 1965, eventually attaining the rank of Marine captain, while at Berkeley, Lutz made a different decision regarding his future. He found himself becoming “totally fascinated with the world of business, particularly the whole bundle of human psychological constructs involved in marketing.”

And he started thinking seriously about combining a career in business with his “second” burning passion in life—cars. Like aviation, that love can also be traced to his youth in Switzerland. A couple of rich uncles drove “great, crazy cars,” including a ’34 Alfa Romeo Zagato, a ’38 Talbot Lago Pourtout, and a ’48 Delahaye, and his father wouldn’t think of having a “dull car,” driving models including an SS Jaguar and an Aston Martin DB2.

At age 29, Lutz received his bachelor’s degree in production management, in 1961 (earning distinction as a Phi Beta Kappa). He received an MBA (with highest honors) in 1962. Soon after that, he got into the auto industry with a series of marketing and, later, management jobs.

Lutz began his automotive career in September 1963 at General Motors, where he held a variety of senior positions in Europe until December 1971. There were several reasons why Lutz left GM that year. One was that BMW offered an eightfold increase in pay. Another was that he’d grown increasingly frustrated with the kind of direction that GM was giving its Opel division in Europe, where he was then the head of sales and marketing. A third reason was his displeasure at being told that “riding a motorcycle and racing cars on weekends didn’t fit the pattern of well-regarded executive behavior.”

For the next three years, he served as executive vice president of sales and marketing at BMW in Munich and as a member of the board of management. There, he also had the opportunity to indulge his love for “two-wheeled transportation by acting as the godfather to the company’s organizationally scattered motorcycle operations.”

He left BMW when he was offered the position of chairman of Ford of Germany. He spent 12 years at Ford Motor Company, where his positions included chairman of Ford of Europe and executive vice president of Ford’s international operations. A member of Ford’s board of directors from 1982 to 1986, for his last position with the company, he was moved to Detroit to serve as executive vice president of truck operations.

In 1986, the 54-year-old executive found himself unable to escape the gnawing feeling that he’d started “running in place” and that he’d “risen about as high as he would go.” The solution was to jump ship and “cast his fortunes with the swashbuckling crew at Chrysler.”

He said that in those days Chrysler was seen as “sort of the last refuge of automotive malcontents,” and that he pretty much fit that description. He remained with Chrysler Corporation until 1998, becoming a member of the board and ultimately reaching the position of vice chairman. He also served as president and chief operating officer, responsible for Chrysler’s car and truck operations worldwide. He led all of Chrysler’s automotive activities, including sales, marketing, product development, manufacturing, and procurement and supply.

Flying to work

His time at Chrysler prompted Lutz to write the first version of his business management book, titled “Guts: The Seven Laws of Business That Made Chrysler the World’s Hottest Car Company,” which was published in 1998. That period was when he also developed the habit of commuting to work in a helicopter.

“I started flying to work when Chrysler moved from basically downtown Detroit out to Auburn Hills, which made a very, very long commute for me by car,” Lutz said. “Tony Bryan, one of our board members at Chrysler, had been the only American Spitfire pilot in the Battle of Britain. I was moaning to him during one board meeting about the long drive I was going to have, and he said, ‘Why don’t you get a helicopter?’ I said, ‘I’ve never trained in helicopters.’ He said, ‘Get yourself trained!’ I said, “But they cost so much money.’ He said, ‘No, they don’t. You can get a Robinson R-22 for about $90,000.’ I said, ‘Really? Is that all?'”

Lutz trained on a Schweizer 300 before getting a Robinson R-22.

“I followed the Robinson R-22 with an Agusta 209, because I thought I wanted a twin-engine helicopter,” he said. “Turned out I didn’t like flying that at all. It’s like driving a bus, and then the fuel systems and everything were so complicated; the post-start, pre-takeoff procedure was so time-consuming. I sold that, and luckily broke even on it.”

Lutz decided next on a McDonnell Douglas MD500, which he still has, and bases in Ann Arbor. He’s not the only helicopter pilot in the family; his wife, Denise, has a fixed-wing certificate, but prefers to fly her Bell 206B JetRanger.

“I think she’s under 1,000 hour’s total time,” Lutz said. “I think she now has more helicopter hours than she does fixed wing.”

Although he still flies to work, the commute is slightly different now. His distinguished career with Chrysler ended in 1998, within months of the company’s merger with Daimler-Benz AG, which resulted in DaimlerChrysler. Previous to that merger, Chrysler broke their rule that required executives to retire at 65.

On the days he’d prefer not to be too challenged, Bob Lutz flies his L-39, which he compares to “a horse that’s very easy to ride and very predictable.”

Lutz stayed on in the position of vice chairman until July 1998. Bob Eaton, CEO of Chrysler following Lee Iacocca, would later express that Lutz was largely responsible for a “monumental transformation in the way Chrysler develops, builds and markets its products.”

Not yet ready to accept a well-deserved “life of ease,” soon after leaving Chrysler, Lutz, 66, became chairman and CEO of Exide, the world’s largest maker of lead-acid batteries. He served as chairman until his resignation on May 17, 2002, and as a member of Exide’s board of directors until May 5, 2004.

Lutz rejoined General Motors in September 2001, as vice chairman of product development. In November of that year, he was named chairman of GM North America. He served in that capacity until April 4, 2005, when he assumed responsibility for global product development.

The L-39 “Albatros” and Alpha Jet

Lutz said he’s never regretted that decision he made at Berkeley that led him away from the military and toward the world of business, but as mentioned earlier, he did at one time suffer “occasional anguish” over not flying military aircraft.

“For a while, it just seemed impossible for a civilian to own a tactical aircraft,” he said. “Now that I’ve got the L-39, and the Alpha Jet, I’m having my cake and eating it, too.”

He says he doesn’t prefer either aircraft over the other.

“I love them both; they’re totally different,” he said. “Some days you feel like being challenged; other days you want to relax and have fun.”

On those days he’d prefer not to be too challenged, Lutz flies the L-39, which he acquired in November 1994 from International Jets, Inc. Former Soviet Air Force Major Alex Makarenko trained him in Gadsden, Ala.

“He was the transition pilot for Rudy Beaver,” Lutz said. “He had been an L-39 instructor pilot in the Soviet Air Force, and he had also spent a lot of time in Iraq, training Iraqi pilots, so he was a very skilled instructor, and a great guy. He would have made a fine addition to any U.S. Marine Corps fighter squadron. He was very meticulous and very thoughtful.”

Lutz acquired about 18 hours of dual instruction before soloing the aircraft in May 1995.

“My last flight in a military jet had been in May 1965,” he said. “So, here we were, almost 30 years to the day.”

He said the L-39 is easy to fly, very good at yanking and banking, and is a very forgiving airplane.

“It’s like a horse that’s very easy to ride and very predictable,” he said.

Lutz currently has about 600 L-39 hours. He acquired his German Alpha Jet last summer from Abbatare Inc., located in Arlington, Wash., at Arlington Airpark. Abbatare, founded by developer Hans von der Hofen, is the only company to have imported German Alpha Jets into the U.S.

After acquiring the jet fighter, Lutz trained at von der Hofen’s Alpha Jets USA. He took his first flight with von der Hofen, and then continued training and got his check ride with the company’s chief pilot, Rick Millson, who served two tours in Vietnam and a tour with the U.S. Navy Blue Angels and is now a corporate pilot.

Lutz said he acquired the Alpha Jet for a few reasons, including the simple fact that it was available, it was “almost new,” and it has a reputation for being a very rugged and reliable airplane. Another big reason is that he’d always wanted something that offered higher performance than the L-39.

“The L-39 is a wonderful airplane, but frankly, other than being a pleasure to fly, very maneuverable and very reliable, let’s face it, it isn’t very fast,” he said. “The Alpha Jet is much more what I’m used to; it’s swept wing and it’s very fast. I’ve got a great power-to-weight ratio. It’s actually very close in performance to the late model Douglas A-4s, like the N models, with the J-57 engines, or with the J-52 engine.”

Lutz said the Alpha Jet is a much more demanding airplane that requires a heightened state of awareness of the angle of attack at all times.

“The angle of attack indicator is almost your primary instrument,” he said. “For high-G, low-altitude flying, and low-altitude yanking and banking, you would need to be at an illegal speed to be able to pull three and four-G turns below about 5,000 feet. Whereas with the L-39, with its straight and very thick wing, you could be at 220/230 knots, and you can do a five-G turn. The Alpha Jet definitely will not let you do that. So, when you’re legal at under 10,000 feet, 250 knots indicated, you’ve got quite a bit of nose-up.”

Lutz bases his L-39 at Ypsilanti’s Willow Run Airport.

“That’s because it requires lots of runway on a hot day,” he said. “The Alpha Jet is at Ann Arbor, because it requires very little runway.”

Lutz said he tries to get as much time as he can in both the Albatros and the Alpha Jet.

“If I can, I try to fly on both Saturday and Sunday, weather permitting,” he said.

With his military background, few would question his ability to fly these jets. But some have questioned if a civilian pilot can fly the same craft safely and proficiently.

“Of all of the fatal accidents in L-39s since they started coming to the United States, I don’t think a single fatal accident involved a former military jet pilot,” Lutz said. “It is possible for somebody with no military experience to be very well-trained and very safe, but I would say the odds are stacked against it.”

In order to fly one of these aircraft, the FAA has several requirements.

“You must have 1,000 hours total, and 500 hours in, quote, ‘aircraft of an equivalent type,'” Lutz said. “So, an air transport pilot or a corporate pilot who flies Learjets or Citations would qualify.”

He added that nowadays, you no longer get a letter of authority.

“You now have to be type certified,” he said.

Memorable flights

Lutz says that much to his wife’s chagrin, he does not use his L-39 as an “executive jet” for going on trips.

“I use it purely the way one would use a sports motorcycle, which is, go out for an hour and a half, do some high-speed stuff, go out over Lake Michigan and do some fairly low-level stuff over the lake,” he said. “I hit my fuel bingo, pull back off, climb back to altitude, do a series of acrobatics, and maybe shoot the simulated flame-out approach. That’s in the L-39. I don’t bother in the Alpha Jet, because it has two engines. Then, I come back, shoot a couple of touch and goes, and I’ve had a workout.”

Because of that scenario, he says a particularly memorable flight occurred last summer when he flew the L-39 up to northern Michigan with his wife to visit friends.

“The trip was great,” he said. “It was a gorgeous weekend and we landed at a field way up near the tip of Michigan.”

He said the Alpha Jet will be perfect for a trip to Mackinac Island, a resort island near Sault Ste. Marie, where the couple also has friends.

“With the car, it’s about a six-hour trip,” he said. “With the Alpha Jet, I figure it’s about 40 minutes. It’s absolutely just below the Canadian border, up in the very northernmost tip of Michigan. It’s a beautiful, peaceful island. No cars are allowed—only horse-drawn buggies. But they do have a three-and-a-half-thousand-foot landing strip up on the high ground. It’s a lot like landing on an aircraft carrier.”

He said that with the Alpha Jet, three and a half thousand feet is plenty, both for takeoffs and landings.

Other loves

In “Guts,” Lutz tells how his love of interesting cars, “no matter what their price or pedigree,” was something he learned not only from those uncles and his father, but also at his mother’s knee. He explained that his father chose vastly different cars for his wife to drive than what he drove.

For example, when his father acquired the SS Jaguar, he acquired a ’37 Czechoslovakian-built Skoda for his wife, believing the Jaguar was “too much car.” Although a “great little car,” Lutz recalled that the clutch and brake pedals were on flimsy castings that came up through the floorboard, resulting in his courageous mother having to stand on the brake pedal on many occasions.

Lutz’s extensive car collection of modern and vintage automobiles includes some sentimental favorites, such as two Vipers, and going further back, his father’s 1952 Aston Martin DB2 Vantage. Vintage cars in his eclectic collection include a 1934 La Salle convertible, 1941 Chrysler convertible, 1952 Citroen, 1934 Riley MPH (semiautomatic, aluminum-bodied sports car) and a Steyr-Pinzgauer, a former Swiss military vehicle he got surplus from the Swiss army a few years ago. The list continues with two 1952 Cunninghams, a 1953 C3 Coupe, a 1952 C4R Le Mans racing replica, an Autokraft Cobra, a 1955 Chrysler 300, a 1978 Dodge Little Red Express pickup, a 1971 Monteverdi High Speed and a 1962 Buick Skylark convertible.

Lutz said he raced briefly, but that it wasn’t a “glorious” racing career.

“I did a little bit in Europe in the ’60’s and ’70’s, and I did some in California and Texas, with the SCCA, in 1954, ’55 and ’56, while I was in the military,” he said. “Then in Europe, I usually ran various corporate cars at events, including doing some racing with the GM France team.”

Lutz smiles and says that professional drivers always told him, “You’re pretty good for a guy who only does this occasionally.”

His office at the General Motors Design Center, in Warren, Mich., is evidence that Bob Lutz is a “plane guy” as well as a “car guy.”

“It’s just like any other sport,” he said. “You’ve got to train, and you’ve got to stay at it. If you’re not dedicated to it, if you sort of do two races a season, you’re just not going to be as good as the guys that do it every weekend.”

Lutz also has nine motorcycles, including one in California and two in Switzerland.

“Currently, the favorite is the BMW K 1200 RS,” he says. “But it’s soon to be displaced from the favorite list by the new BMW K 1200 S, which is probably—together with the Suzuki Hayabusa, and I have one of those, too—the world’s fastest legal, road-going conveyance. It’s the first time that BMW has ever done a super-bike. With speed probably in the area of 190 miles an hour, it’s a superb bike.”

In case you’re wondering

On March 31, Lutz arrived in Denver to be the keynote luncheon speaker at AutoVenture 2005. The fact that he exited the company Gulfstream V at Centennial Airport prompted a question as to what other aircraft General Motors utilizes. John McDonald, manager of communications for General Motors Air Transportation Services, said the fleet operates GVs and Citation Xs. He quickly added that Lutz stays out of these cockpits.

“He’s not type certified to operate those aircraft and he does not fly them,” said McDonald.

McDonald, whose position supports GM’s Economic Development and Enterprise Services Group, explains that the Enterprise Services Group includes worldwide travel, so corporate flight falls in their area of responsibility.

“The corporate aircraft that we have, as with other large, multinational corporations, are made available to our senior level executives for worldwide travel,” McDonald said. “That’s obviously for the convenience factor, but it’s also for the security factor. As a multinational corporation, we have security concerns and need to make sure that top executives are in a secure environment when they travel.”

He said that’s not only air travel, but ground transportation as well.

“We have aircraft available for them to use when they would like to use them, and we also have a travel service that provides an interface through American Express to provide corporate travel services that include flight ops, like other aircraft that are operated on commercial airlines,” he said.

He said GM’s corporate aircraft are also part of the Part 135 operation.

“We charter out to other folks,” he said. “There are people that come in that use these aircraft that are commercial customers as well. They’re not just dedicated to General Motors. That’s obviously because of the fact that these aircraft are very expensive to operate and maintain. We don’t have the need to have them 24 hours a day, so it helps to cover the expense.”

Although a top executive in the cockpit of one of the GM aircraft might be a concern, it doesn’t seem to be a problem this time around that Lutz’s “recreational” activities don’t fit the pattern of “well-regarded executive behavior.”

Bob Lutz, shown with Rick Millson, chief pilot for Alpha Jets USA and former U.S. Navy Blue Angels team member, acquired his German Alpha Jet last summer from Abbatare Inc.

“”I know Mr. Lutz is a very passionate aviator. He’s very committed when it comes to taking part in aviation activities, so it doesn’t surprise us he wanted to chat with you,” said McDonald.

Although GM seems to have gotten used to his maverick behavior, Lutz’s past, and present, has raised a few questions. He was recently questioned concerning some of GM’s powerful cars, in particular the Cadillac XLR-V, which will be enhanced by a supercharger that will increase its power to 440 hp.

Lutz was asked if that was “an environmentally safe road to take,” and if the reason for the innovation was that he was a military jet pilot who likes power and speed. His answer was, “No, it’s not because I’m a military jet pilot and like power and speed. It’s because even with all the hysteria over fuel prices, there’s still a segment of the population that wants big engines.”

“To turn your back to that and say, ‘I don’t think we should be doing that,’ just means that we wouldn’t be going where customers want to go,” he said, and then grinned. “Having said that, I like power and I like speed, but that’s not the reason we build powerful and fast cars.”

Power and speed weren’t the only things on his mind back at Chrysler when Lutz dreamed up the Cobra-inspired Dodge Viper, which vastly affected the public image of the “dull, stodgy, beleaguered K-car” company, beginning with its appearance as a concept car at the Detroit auto show in 1989. In his book, Lutz spends quite a bit of time talking about right-brained (creative) and left-brained (rational) thinking, and said if ever there was a “right (and right-brained) product,” it was the Viper.

The retro car, the fastest and most expensive vehicle ever mass-produced in the United States, was brought to market in three years on a modest budget of $80 million. It became reality, with the help of Chrysler consultant Carroll Shelby, in 1992. Lutz said the Viper became a “potent symbol” of Chrysler’s new spirit, as well as its unconventional thinking and daring, and that the result was a beautiful example “of what can happen when the whole brain is engaged.”

Lutz didn’t need to look any further than Centennial Airport to find an example of a “right-brained” product in the aviation industry today.

“The Javelin—absolutely,” he said. “I mean, somebody said, ‘This is an object of pure lust. It’s completely unreasonable: ‘If I build it, they will come.’ And they surely will.”

Before flying out of APA, he stopped to admire the Javelin mockup, and to discuss the tandem-seat, twin-turbofan executive jet with Charlie Johnson, Aviation Technology Group executive vice president of operations and former president and COO of Cessna. His interest in the innovative jet prompted the question as to what Lutz considered the single most significant aircraft and aircraft designer.

Bob Lutz said he’s never regretted his decision to give up a military career for the world of business, but did at one time suffer “occasional anguish” over not flying military aircraft.

“I would say on aircraft design, other than the Wright Flyer, certainly the Messerschmitt 262, the world’s first high-performance jet fighter that flew in the late ’40s,” he said. “There are now re-creations or replicas being built. That and/or the SR-71 Blackbird, which is just an incredible airplane, especially when you think when that was designed and built.”

As far as aircraft designers, Lutz said that without question, Kelly Johnson gets his vote.

“I have unbelievable admiration for that guy,” he said.

That admiration goes back several decades. While at Ford in the early 1980s, for example, Lutz had an idea he thought would improve the company’s speed and lack of teamwork in product development. He invited Johnson, the head of Lockheed’s “Skunk Works,” to address the company.

“They produced America’s first jet fighter, sketch to flight, in just 100 days, partly by cutting his engineering group from 8,000 to 800,” he said.

Lutz had thought the message might help shake things up, but the response wasn’t what he had expected. Johnson’s hour-long talk on teamwork, elimination of waste, fast prototyping, and “all the other virtues that today’s product development experts hold dear,” got “hardly a rise out of Ford’s executives.” He says someone might have been influenced, though, because Ford, ultimately, did change.

Lutz has been called in more than once to help troubled automotive companies. When asked to name an aviation-related company that he would’ve wanted to rescue, he again has a quick answer.

“I actually was involved in an aviation-related company,” he said. “I was a major investor in Mooney, before it went Chapter 11, the most recent time.”

He’s also given some thought to what other aircraft he might consider owning in the future.

I think one thing that I would like is if something like a twin-seat Northrop F-5 became available,” he said. “There are some trainer versions. It never sold in the U.S., but some of them are being imported back. Or when the Swiss Air Force gets rid of their single-seat F-5s. A Northrop F-5, to me, is just one of the slickest, most beautiful, most desirable light fighters that the world has ever seen.”

Bob Lutz flashes those gathered at Centennial Airport shortly before his takeoff. Airport Journals Publisher Jerry Lips is in the background.

Lutz takes the longest time to ponder the question as to what aircraft he would change, if he could revamp even one.

“I enjoy looking at them so much,” he eventually says. “I think airplanes are so beautiful. That’s one of the thrills of the military jets; they’re so slick and the shapes are so intriguing and so dynamic that I love them all. I can’t fault them. I even love the Soviet stuff—the Sukhoi 27, the MiG-29. They’re just all beautiful.”

SEE ALSO “GM’S BOB LUTZ SETS THE RECORD STRAIGHT AT AUTOVENTURE 2005“