By Deb Smith

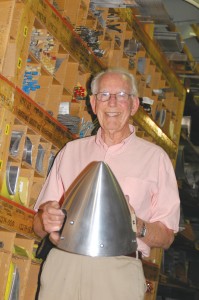

At 84 years young, Bob Williams still plays an active role as vice president of Aurora-based Univair, working eight hours a day, four days a week.

To most people, the sky is the limit, but for Bob Williams, the sky is just simply home.

The high art of barnstorming thrived in North America during the early 1920s. Orville and Wilbur Wright’s magic flying machine—-now in full-scale production–had literally captured the hearts of the American public from coast to coast, manifesting the promise of the future in a few yards of fabric wrapped around a lightweight wooden frame.

Leather-clad birdmen that soared above the grassy fields in these magnificent contraptions called airplanes drew homemakers from their chores, children from their play, and farmers from their tractors. Each hoped to get just a glimpse of what would eventually become modern aviation.

In the midst of all the barnstorming fuss, George and Gertrude Williams made their home in Kennedy, N.Y. It was a quiet little corner of the world just outside the city of Jamestown. Gertrude was a homemaker and George, who was a bit of an entrepreneur, owned a small fleet of dump trucks he hired out to the county highway works.

On a frosty December morn in 1920, the couple warmly welcomed Robert Mason Williams into the world. Because the town of Kennedy was so small-—barely more than 500 citizens—-there was no local hospital. According to Williams, his parents had to make the trek to the nearest “big city,” which at the time was Jamestown.

The younger Williams spent the majority of his childhood in rural New York, working with his father in a variety of moneymaking adventures.

“At one time, my father had a sawmill,” recalled Williams. “I spent an awful lot of time around the mill. … I was driving logging trucks at 15.”

During the 1930s, about the same time Williams was busy jamming gears at the sawmill, barnstormers were feeling the pressure of competition. Countless daredevil aviators had entered the market, and with so many taking to the skies performing loops and rolls, crowds were starting to demand something different, more complex, and increasingly dangerous.

The general public wanted more thrills. But with added risk and cost standing between them and a paycheck, many barnstormers chose not to push the envelope with aerobatics, and instead opted to travel the country and simply sell rides.

It was safe. It was profitable. And most importantly, they could still be the center of attention. One such barnstormer made his way to rural New York.

On a sunny summer day in the late 1930s, Williams’ father noticed a dancing speck in the skies above and watched closely as it winged its way to a nearby grassy field. Taking his son by the hand, the elder Williams rushed toward the field where a magnificent bi-winged twin-engine Curtiss Condor had just rolled to a stop.

“We made it up there and it was the most wonderful machine I had ever seen,” said Williams. “Having been around all those trucks and the sawmill, I had a bit of an eye for anything mechanical and this was beyond anything I had ever imagined.”

Robert Williams was ecstatic when his father purchased a ride for him. Spellbound, he climbed into the cockpit.

With a summer breeze at their back and nothing but blue sky ahead, Williams and the unnamed pilot roared down the makeshift runway, clipping the tops off the tall grass along the way. The pilot pulled back on the stick, the plane rotated and Williams was in love.

“I said to myself, ‘This flying stuff feels pretty good,'” chuckled Williams.

Decisions, decisions

While Williams readily admits his summertime flight with the mysterious flyer had a deep impact on his life, he didn’t recognize it as the pinnacle event that placed him on the path to becoming a pilot.

In high school, he excelled in music, participating in band, orchestra and choir, and was even an accomplished bassoonist. It appeared as if music might be his life’s calling.

“We had a little jazz band in high school,” he recalled. “We got permission from the principal of the school on every Friday night, to earn some money, and we’d have a dance in the gym. I think kids paid ten cents or something.”

When Williams graduated in 1939 from Falconer High School in Falconer, N.Y., he was still undecided which direction in life to pursue.

“It was a big toss up at the time to know what to do,” he said. “Back at the time I was about to graduate, the Coast Guard was looking for musicians to play in their bands. However, I decided that the musician’s life was not really what anybody ought to get into—-and I’m glad I made that decision.”

Nevertheless, Williams acknowledged he had to do something.

“At that time, things were still pretty hard up,” he recalled. “So I went down to Alfred University and went to school there for just about a year. New York State had an agricultural school on the premises, but it was more than just agricultural studies. It was also a technical school. What you really got was the last two years of your college education.”

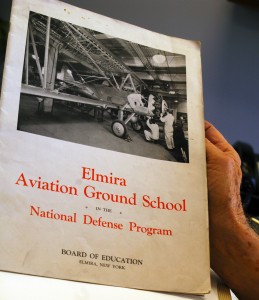

That sounded like a good plan, until he heard about an aviation ground school in Elmira, N.Y.

“It was only about 150 miles down the road from where we were,” he said.

A honey of a deal

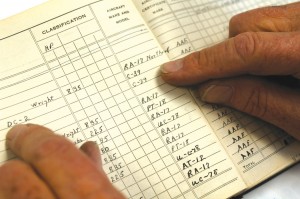

With a logbook that reads more like an Army Air Corps inventory list, Bob Williams chuckles that he got to fly a different airframe almost everyday.

Williams transferred to pursue an aircraft and engine certificate.

The school had everything he’d been looking for-—plenty of mechanical courses and lots of hands-on training. It was part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s National Youth Administration program.

According to Williams, that was what made the option a possibility. Because of the growing numbers of unemployed youth of the 1930s, conservatives saw disillusioned young people as a fertile ground for bad politics. Eleanor Roosevelt worried that long-term unemployment and borderline poverty would undermine young Americans’ faith in democracy.

“I live in real terror when I think we may be losing this generation,” she said in an interview with the New York Times. “We have got to bring these young people into the active life of the community and make them feel they are necessary.”

Educators also feared that without some type of financial support from the government, college enrollment would suffer. Working closely with educators and relief officials, she pushed her husband, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, to sign an executive order in June 1935 establishing the National Youth Administration, a New Deal program designed specifically to address the problem of unemployment among Depression-era youngsters.

“It was great,” said Williams. “Nobody had any money back then, and the National Youth Administration was what helped a lot of us make it during some really rough times.”

For Williams, the deal couldn’t have been any sweeter.

“While we were going to the school, which was a 2,000-hour complete engine course, and took about two and a half years to complete, we had to earn room and board,” said Williams. “We’d cut grass, clean the school, wash windows, clean bathrooms and all that kind of stuff to earn $30.”

National Youth Administration students at the Elmira school earned $30 for 80 hours of work. A deduction of $21.99 was made by the school to cover room and board, leaving each student with $8.01.

“Isn’t that something?” asked Williams with a smile.

The other value-added factor for Williams was the fact that the Elmira Aviation Ground School was located in an old knitting mill near the Harris Hill primary glider area. In addition to his National Youth Administration wages, Williams also worked part time at the Schweizer Company, which was conveniently located upstairs from the school.

“I did a lot of welding on Schweizer fuselages up there,” he explained. “It was great.”

Williams recalled that Harris Hill was the site of several international soaring meets in the 1930s and 1940s.

“While we were in school we’d often go up to the meets and do the ground handling of the gliders,” he said.

A nation calls

It was 1942 and World War II was starting to wind up. Allied troops were on the move and Bob Williams wanted to help. He also wanted to be a flyer.

“Although it didn’t really hit me at the time, I realized the airplane ride I had when I was a kid always stayed with me,” said Williams. “I never really forgot it.”

At that time, the fastest way into a cockpit was though the Aviation Cadet Program. In the early 1940s, the Army Air Corps faced a second war and was once again short of pilots. In June 1941, Congress created the grade of aviation cadet, and the Army launched an extensive flight-training program, producing thousands of pilots, bombardiers and navigators.

“I signed up and took the entrance exam while I was still in school,” said Williams.

He was called to duty before he could finish his final exam at the Elmira school. He was accepted into the Aviation Cadet Program, where he graduated with class 43-E at Albany, Ga., earning both his wings and a commission.

“Then came my first assignment,” said Williams. “When you’re still a cadet, you pretty much live every day in fear–of getting washed out at anytime for just about anything. I was no exception.”

With graduation just a day away, Williams and his buddies had gone into Albany, Ga., for the night to celebrate their long-awaited pinning ceremony.

“I’m standing on the street corner waiting to catch the bus to go back to the field for graduation and the base commander came by in his car,” said Williams. “It scared me to death. He stopped the car and said, ‘Are you going out to the field?'”

Williams admits he thought that was a dumb question since it was graduation day.

“I said, ‘Yes, sir, I am,'” he recalled.

“Well, get in,” barked the commander.

“So we’re driving along and the commander asked me what my name was,” said Williams. “So I told him.”

“Williams,” pondered the commander. “You’ve got a great assignment.”

As part of FDR’s National Youth Administration Program, Bob Williams attended the Elmira Aviation Ground School in Elmira, N.Y. Williams earned $30 for 80 hours of work, of which $21.99 was deducted for living expenses.

“I couldn’t believe it,” remembered Williams. “There must have been a hundred guys in my unit, so how could he know that I had a great assignment simply by asking me my name. It just didn’t make sense.”

The commander didn’t elaborate, and his cryptic message raised Williams’ anxiety level even more.

“I was dying to find out,” he said.

After graduation, all the assignments were posted in a common area and Williams made his way to the front. The sign said, “WILLIAMS, ROBERT M., PATTERSON FIELD.”

“I found out that I wasn’t assigned to the next grade of pilot training like I should’ve been,” he said. “I was assigned to Patterson Field, Air Materiel Headquarters in Dayton. The reason they did that was they didn’t have any flying officers graduating at that time that had any maintenance experience.”

Williams enjoyed the assignment–and a corner office with a spectacular view of the hangar floor.

“I had a good time there, because being in the maintenance field I got to fly all the airplanes there were,” he said. “We did a lot of ferrying work and a lot of freight work in the C-17. We also ran a little airline there flying parts to all the surrounding bases using the UC-64 Norseman.”

Williams has 500 hours in just the UC-64 alone. In his position as a maintenance test pilot, he racked up the hours on just about everything the Air Force had. A short list would include the Douglas DC-2, DC-3 (C-47), B-23, A-20, and A-24, as well as the P-38, P-39, P-40, P-47, P-51 and B-17. Williams also has flown a variety of civil aircraft.

Charting a new course

It was 1946 and Captain Williams was ready to “punch out.” He left the service with an honorable discharge and went right back to the Elmira Aviation Ground School to take his final exam. He passed.

With his certificate in hand, he went back to work with the Schweitzer Company. But Williams had changed.

“They put me in the inspection department,” he said with a grimace. “I was a young guy, and had been flying all those airplanes in WWII. I wasn’t really cut out for factory work.”

A determined Williams walked across the field and landed a job as the fixed base operator. In 1947, he garnered a position as the executive pilot for William W. Sinclaire of the Corning Glass Works. One job led to another.

Sky Ranch Airport and Univair

While flying for Sinclaire, Williams got to know the friendly folks at the Sky Ranch Airport in Aurora, Colo. Rumor had it that the small field would soon be losing its mechanic and he fancied himself as a suitable replacement.

In 1949, he moved to Denver to fill that position, but once again, one job led to another. However, this would be more than a job. It would become Williams’ lifelong passion.

Eddie Dyer and Don Vest had a small aircraft company known as Universal Aircraft Industries, which would eventually become Univair Aircraft. Williams, with his extensive experience in maintenance, was hired as the manager for the repair division.

“We had a contract from Fort Carson to do maintenance work on L-19s and Beavers and helicopters for quite a few years,” said Williams. “I got a lot of time in Beavers.”

After the death of Eddie Dyer, Williams reluctantly left aviation and entered the asphalt paving business. But within five years, that company was sold.

He returned to Colorado–and to aviation. In 1967, Williams married Veda Dyer, Eddie Dyer’s widow and president of Univair. They injected their collective heart and soul into the company and the aviation community, making not only a business venture, but a partnership in the truest sense. Together they founded the Colorado Chapter of the Silver Wings Fraternity.

Veda Dyer Williams was an aviation pioneer in her own right, having soloed in 1943. Some say she accomplished more for Colorado aviation without a pilot’s license than many with licenses accomplished. Robert and Veda Dyer Williams were inducted into the Colorado Aviation Hall of Fame in 1980, becoming the only couple to be enshrined simultaneously. Six years later, in 1986, Veda Dyer Williams passed away following a long illness.

Today, Bob Williams remains at Univair as vice president. At the age of 84, he still plays an active role in the growing global company, working eight hours a day four days a week.

In July 1988, he married the former Genelle G. Cauthen. They reside in Castle Rock, Colo.