Part of the starting field in the impound area at Ciudad Juarez the day before the start of the first Carrera Panamericana.

By Daryl E. Murphy

It was summer 1945. Hershel McGriff sat in his father’s prewar Hudson on the damp clay track that was Portland Speedway, hoping that no one would recognize him; he had told his father that he was taking the car for a Sunday date.

World War II had ended just a month earlier. Many things inaccessible during the war were available again, although gas, tires and particularly automobiles were still scarce. But the local race promoter was celebrating Japan’s surrender by staging a “race-what-you-bring” event, open to all comers.

Though he was just 17, McGriff had been working for a logging company for three years, driving heavy trucks in the mountains near Portland. He developed a feel for speed and handling on the tricky, winding Oregon dirt pathways. A race against other drivers would help him decide if he was as good as he thought he was.

Starting on the outside of the sixth row—slowest in the field—McGriff avoided a crashed Ford at the gun and flung the Hudson around the track. By the 10th of a scheduled 25 laps, he was in sixth place, but when a wheel came off, the field lapped him. Then, on the last lap, the battery fell out of the car, and he had to coast across the finish line in 11th place.

It wasn’t an auspicious beginning, but it was fun. McGriff Sr., however, wasn’t amused and demanded $180 from his son for repairs to the family car.

By spring 1946, young McGriff had saved enough money to buy a used 1940 Ford, and Portland Speedway had paved its oval for a scheduled 100-lap opening race. Preparing his car with the help of friend Ray Elliott, McGriff entered the race, knowing he could go the distance. He watched the veteran drivers and local hotshots battle for the lead during the first 40 laps, only to retire against a wall or smoke into the pits. Pacing himself to his best speed, by lap 80 he was in second place by a straightaway. By the time the checkered flag had fallen, McGriff had passed the leader and won the second race he had ever driven.

A contest of heroic proportions

In 1950, Mexico was, to some, an ancient and backward country stuck in the wrong century. It had given the United States tremendous economic support during the war, but the average American’s view of the land south of the border was of an unstable and uneducated nation, with a population that filled its days lazing in the shade under sombreros and its nights robbing tourists at gunpoint.

Texans thought even worse. Their prejudice had historic roots; once a part of Mexico, the Republic of Texas and later the Lone Star State had been created amidst bloody battles just over a century earlier. Texans hadn’t forgotten the Alamo. As stated in T.R. Fehrenbach’s Texas political history research, by the middle of the 20th century, economically superior Texans looked upon Mexicans as a “useful underclass.”

Postwar prosperity had, among other things, allowed the Americas to resume grand plans for an international road to be known as the Pan-American Highway. As Americans laid asphalt and concrete across Middle America, Mexicans were rushing to make more of their country accessible to both trade and tourist, hoping to bring a new economic and social awareness to the country.

Two of the roads in Mexico—the Central Highway from the Texas border to Mexico City and the Cristobal Colon (Christopher Columbus) from the capital to the Guatemalan border—had been under construction since 1935 and were nearly complete. By the time they were done, the two highways would represent about one-fourth of all the paved roads in the country and cost 500 million pesos, or about $58 million.

With the anticipation of a link across Mexico connecting North America with Central America, the Asociacion Mexicana Automobilistica and the Asociation Nacional Automovilistica began to talk about an event that would prove and publicize the nation’s new artery. Their perfect answer was a race. No race of any significance had been held in the country since 1939. And it couldn’t be just a little race, either. It had to be an event that would make the world sit up and take notice. A contest of heroic proportions and vast distances. A race that would bear witness to what Mexico had accomplished and what it was capable of doing.

Committees were organized, inquiries were made, and in March 1949, the ANA magazine began publishing a series of features about the new highway and European road races—without making a connection between the two. Mexican President Miguel Aleman and Secretary of Communications Agustin Garcia Lopez nonetheless offered their support—should such a race ever be scheduled.

By August, the complete list of committees was publicized and work began, still without a formal date for the start of the race because of uncertainty about when the road would be completed. A successful Mexico City Pontiac dealer, Antonio Cornejo, was appointed the race’s general manager. Stanford-educated, the upper-class Cornejo was fluent in both English and Spanish, and was a man used to getting things accomplished.

One of his first tasks was to find financing. The Mexican government provided a 250,000-peso ($28,900) seed fund, and Cornejo raised twice that amount from the individual states through which the race would pass and from contractors and manufacturers of cars, accessories and tires. Of the 750,000-peso fund, half would be designated as prize money.

Needing outside help, Cornejo contacted the American Automobile Association, then the biggest and most powerful race sanctioning body in the U.S., to loan technical assistance in organization. Press releases were sent to hundreds of North American newspapers. Copies of the rules and entry blanks were sent to 600 registered AAA race car owners, drivers and mechanics.

By mid-December 1949, Mexican Public Works engineers were able to forecast that by February 1950 the highway would be open and all river crossings would have either permanent bridges or fords proper enough to permit a high-speed race.

The date for the start was set for May 5, Cinco de Mayo, the national holiday commemorating the 1862 Mexican victory over the invading French at Puebla. The place would be Ciudad Juárez, across the Rio Grande from El Paso, Texas.

El Paso was relatively remote from the rest of the state. In 1950, it was a hard day’s drive from any other large city in Texas: 560 miles from San Antonio, more than 600 miles from Dallas and 750 miles from Houston.

This meant that the racers and their crews headed for Mexico would be virtually inaccessible, so would need to have everything they needed before they left home.

For you a rose in Portland grows

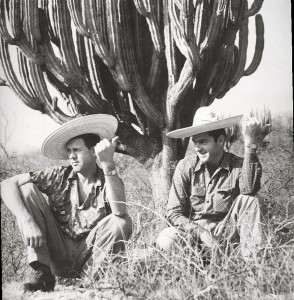

Bill France (left) and Curtis Turner almost had to hitch a ride back to Dixie after wrecking one car and disqualifying another.

In the five years since his first race, McGriff had done well in Northwest stock car racing. By the spring of 1950, he had entered 12 races and won eight, capping the 1949 season as the Northwest stock car champion. At 22, he was a talented and already experienced oval-track racer. He had married his high school sweetheart in 1948, and between races still drove a truck for the lumber industry.

One of his biggest fans was Roy Sundstrom, a Portland neighbor who helped McGriff and Elliott maintain the succession of Fords that McGriff campaigned and reveled in the pit life at the racetrack.

Elliott was the one who brought the news of the Mexican road race. He belonged to the AAA, and showed the two the race promotion letter he’d received. Sundstrom and McGriff often discussed the contest over the next several weeks, but realized that running in the race would require a great deal of money—which neither had. The planning was fun, but without backing, they couldn’t swing an entry.

Then one Saturday in March, McGriff heard the honking of a horn in his driveway. He went to the door and saw Sundstrom and Elliott in a brand-new Oldsmobile 88 two-door coupe, smiling and motioning him to the car.

“Think this’ll get you to Mexico, Hersh?” asked a beaming Sundstrom.

An elated McGriff slid into the driver’s seat and started the V-8 engine.

“Sounds like a stuck lifter,” he said solemnly as he listened. “We’ll need lots of tires and a bigger fuel tank. … Good, it’s got a stick shift; that Hydramatic could be trouble in the mountains.”

The three partners spent the rest of the weekend planning their great adventure. They all agreed that McGriff and Sundstrom, the car’s owner, would split the first 80 percent of any winnings; Elliott would get the rest. Sundstrom posted their entry fee, and the trio went to work preparing the Olds.

Sundstrom hired a sign painter to decorate the side of the Oldsmobile with roses on its doors and the slogan, “For you a rose in Portland grows.” With a rush of civic pride, he named the vehicle The Spirit of Portland.

Elliott found a 50-gallon saddle tank from a wrecked International truck, and by Friday, he had modified and mounted it in the Oldsmobile’s trunk. The trio found that a local General Tire dealer had squeegees on sale for $12 apiece, so they bought eight. They all tinkered with the car, and although none of them knew much about serious mechanics, they did learn to mount the tires, a skill that would come in handy in Mexico.

On April 15, McGriff paid all his bills, bought groceries for his young family and left Portland with Elliott in the right seat and Sundstrom perched unceremoniously on top of a pile of tires in the cramped rear seat. The first night out, they stayed in Reno, Nev., primarily because of motel rates that were among the lowest in the country. McGriff, who had left home virtually broke, put a dime in a slot machine and hit the jackpot.

“Damn! With luck like that, we’re bound to win the race,” he said as he struggled to carry the 1,500 coins to the cashier.

When the Oregon Oldsmobile arrived in El Paso, the men found the race headquarters and checked in.

Help from California

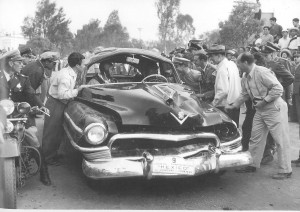

Rudolpho Castaneda drove a Cadillac sponsored by the Mexican presidential staff. He crashed twice before reaching Parral on the second leg. Bravely continuing on, he finished the race in 26th place.

The 2,178-mile race would be in nine legs, varying in distances from 84 miles to 334 miles each, over a period of five days. It would cover the entire length of Mexico, from Ciudad Juárez on the Rio Grande to the tiny village of El Ocotal on the Guatemalan border.

Cars would start the race in numerical order at one-minute intervals, with five minutes between each group of 20. On subsequent legs, they’d start in the order of finish from the previous leg. Each team would be furnished a route book to record leg and accumulated times.

Cash prizes offered for each leg were 2,000 pesos ($232) for the win, 1,000 pesos ($116) for second and 500 pesos ($58) for third. The first three places at the end of the race would receive 150,000 pesos ($17,442), 100,000 pesos ($11,630) and 50,000 pesos ($5,815) in prize money. In the perspective of the time, the average price of a new 1950 Oldsmobile 88 was about 16,800 pesos ($2,100). The narrow prize money structure put competition on an all-or-nothing basis; many U.S. drivers hesitated to post the $290.75 entry fee, after assessing their chances.

Bob Estes, a California-based Lincoln-Mercury dealer and race car owner, was interested in sponsoring AAA driver Johnny Mantz’ Lincoln in the race. The two appointed themselves as ambassadors of the Southern California racing fraternity and went to Mexico. They drove nearly the entire course in a 1949 Lincoln borrowed from Estes’ lot, inspecting and practicing. They used the Pemex race gasoline, talked to race manager Cornejo and even checked out the race committee’s books. Satisfied that everything was on the up-and-up, they returned to Los Angeles and took out an ad in the Los Angeles Times sanctioning California entrants.

Rules for car preparation were simple: keep it strictly stock. Allowable modifications included a 0.030 in. overbore for 1949-50 models and a 0.060 in. overbore for older models, replacement of shocks with stronger units, and removal of the rear seat to install extra gas tanks and to carry spares and tools. An open exhaust was specifically forbidden, and seatbelts and helmets were encouraged but not required.

The organizing committee was even going to provide room and board for all participants during the race—along with free gas and oil. At the start of every leg, each crew would be provided a sack lunch and three warm Coca-Colas, plus the racers could look forward to a banquet each night at the stopover city.

A potpourri of cars

The American concept of fast cars had always been two-ton luxury behemoths popularized in the twenties by Duesenberg, Packard and the like. So the mindset, even among the racers, was that bigger cars were faster and more stable. That was partly true. The most expensive—ergo the biggest—American automobiles of 1950 coincidentally had the most horsepower.

Packard and Lincoln were producing plenty of power from their old L-head engines. In fact, Packard had the most efficient of the group, with a better horsepower-per-cubic inch figure than the rest, but the flathead engine was nearing the end of its usefulness.

Cadillac and Oldsmobile had independently introduced two new, modern overhead valve V-8s in 1949. These V-8s had shorter, more rigid crankshafts than their competitors and were lighter, higher-revving and yet more stressed for elevated compression ratios. The 331-ci, 160-hp Cadillac unit was 220 pounds lighter and 10 hp stronger than the 346-ci L-head V-8 it replaced, and it had five main bearings instead of three.

When the smaller Olds Rocket—303 ci and 135 hp—was dropped into the light sedan body of the 76/88 series, its nimbleness and favorable power-to-weight ratio made it an instant hit with stock car racers. Oldsmobile had won five of the eight National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing Grand National races in 1949, and Olds driver Red Byron was national champion.

A drawing for the Carrera Panamericana starting positions was held in Mexico City on April 29, 1950, and entrants began arriving in Ciudad Juarez on May 2 for inspection. Entry fees were posted for 132 cars—59 by Americans, predominantly Californians and Texans.

Italian Formula One drivers Piero Taruffi and Felice Bonetto entered a pair of Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 coupes. Taruffi, whose specialty was road events, had been successful in the Mille Miglia (third in 1933, fourth in 1934) and the Targa Florio (second in 1939 and 1948) and was undoubtedly the most experienced road racer in the field. Other European competition came from Frenchman Jean Trevoux, who entered a Type 175 Delahaye.

Hershel McGriff and Ray Elliott never won any legs but stayed consistently high in the standings. Their average speed for the 2,135 miles was 78.421 mph.

The field was filled out by Mexican truck and taxi drivers equipped with little more than a desire to compete, along with a group of middle-aged “gringo” tourists who viewed the race as a chance to drive at speed across Mexico without the distraction of oncoming traffic. Among the less serious were Marie Brookerson and Ross Barton, with Brookerson’s 1949 Lincoln Cosmopolitan. Brookerson lived near Wilcox, Ariz., and had met Barton when bad weather had forced the private pilot down onto her ranch. Both single and in their sixties, they fell in love and decided to get married if they finished the race.

Arthur and Marie Boone, a retired couple from New York City, entered their new Buick for the high-speed trip across Mexico, and Mrs. H.R. Lammons of Jacksonville, Texas, used the sides of her 1948 Buick as a billboard for the brassieres she sold.

The oldest cars in the race were a 1937 Hudson, driven by Ismael Alvarez of Mexico City, and Chicagoan Hugh Reilly’s 1937 Cord 812.

“The boys from Thunder Road” made up the southern contingent. Bill France was their ersatz leader. A racer since the first Daytona Beach race in 1936, France was denied sanction by the AAA contest board in 1947 to stage stock car events. The AAA was interested only in the open-wheel, oval track racing it had always controlled, so France formed a dedicated group: NASCAR.

Accompanying France as the co-driver of a 1950 Nash Ambassador was consummate wild man Curtis Turner. Reformed moonshine drivers Bob and Fonty Flock from Atlanta, Ga., entered a Lincoln. Fonty, called “the funniest man in racing” by his NASCAR buddies, would later gain notoriety as the only person ever to win Darlington while wearing Bermuda shorts. Johnny Mantz’ co-driver was California engine and chassis wizard Bill Stroppe.

Thomas A. Deal, a portly El Paso Cadillac dealer, had tested all the cars at his lot and selected a 1950 four-door to enter. C.R. Royal, an El Paso Chrysler dealer, hired Bill Sterling, a tall and lanky local truck driver and amateur racer who was familiar with Mexico’s roads, to drive a Cadillac.

Joel Thorne, whose Art Sparks-built Thorne Engineering Special had won the Indianapolis 500 in 1946 under George Robson, entered his personal 1949 Cadillac. Thorne, a full-time California playboy and sometime millionaire, had also competed at Indy, finishing ninth in 1938, seventh in 1939 and fifth in 1940. Brothers and Pikes Peak Hill Climb champions Al and Ralph Rogers also entered a Cadillac.

The 132 starters assembled promptly at 6 a.m. on May 5, and while waiting for the start, heard news of the race’s first accident. A Mexican official, zealously speeding ahead of the racers toward his post in Chihuahua, failed to negotiate the only curve on the 233-mile leg and rolled his Pontiac station wagon. Unhurt, he was assisted by soldiers guarding the course, who righted his car and sent him on his way, a sadder but wiser driver.

Havoc

After four hours of festivities and speeches, the governor of the state of Chihuahua waved the Mexican flag to start car number one, Mexico City’s Luis Iglesias Davalos, driving a 1950 Hudson.

The first section of the Carrera Panamericana was a high-speed run across a flat, hot desert, and tires began blowing like popcorn. Thorne wasn’t quite out of sight of the starting line when he wrecked his car. Another Cadillac, entered on behalf of the Mexican presidential staff, set the dubious record of crashing twice on the leg but bore bravely on, its top caved in, its windshield missing, and its driver’s arm encased in plaster. The race’s only fatality occurred 19 miles outside Juarez, when Guatemalan Enrique Hachmeister lost control of his Lincoln and crashed.

At Chihuahua, 113 cars were still in the running. After the tabulations were gathered, Sterling was declared leg one winner. He had made the run in 2:19:12, with an average speed slightly over 100 mph. One minute back was Anthony Musto of Chicago in another Cadillac, then Mantz in the Estes Lincoln. McGriff was seventh.

Taruffi said that no American stock car could sustain high enough speeds to average 100 mph over that distance; Motor Trend had managed to coax only 95.44 mph out of a new Cadillac in testing earlier that year. But most of the serious owners and drivers in the race were experienced hot-rodders, race car preparers and dealers, any of them capable of some “creative tuning.”

The proclaimed top speed of Taruffi’s Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 was 90 mph; it averaged 89 mph on the leg. He hoped to make up for the big sedan’s slower speed in the desert with its agility in the mountains.

The next morning, Sterling’s Cadillac had a new sign on its sides, proclaiming that it held the World’s Stock Car Record.

On leg two, a 186-mile run to Parral, the race moved into the foothills. Miraculously, no accidents occurred, and only three cars dropped out. George Lynch won the leg, driving a Cadillac at 95 mph. Mantz and Sterling followed.

The bookkeeping begins

At this point, racers had to start keeping track of their leg times and positions, as well as total elapsed times and standings in the race. Sterling, who had won leg one and was third on leg two, was leading in overall time, one minute ahead of Mantz. Lynch moved into third, Bud Sennett was fourth and McGriff was fifth.

Legs two and three were run on the same day, with a short mandatory layover in Parral. Tony Musto reached the finish line in Parral in good enough time to remain among the leaders, but ignored the checkered flag and tore on through town toward the finish of leg three at Durango. He was summarily disqualified for failure to present his logbook and make the compulsory stop at Parral, but it was all academic after he and his co-driver were found sitting atop their wrecked Cadillac 12 miles short of the finish line at Durango some hours later.

With a fifth-place finish, Trevoux moved his Delahaye Type 175 to 13th overall. Taruffi had tire problems that held him to 28th on the leg, and Alfa Romeo teammate Bonetto finished 31st. Alvarez maintained last place in his 1937 Hudson and would be mercifully forced out on the next leg with transmission trouble.

More mountains, less speed and numerous position changes were recorded after the 110 survivors reached Durango at the end of the 250-mile leg three.

A national event

Hershel McGriff passes Lewis Hawkins on the torturous final leg in the mountains near Guatemala. As he crossed the finish line at El Ocotal, McGriff hit a dip in the road and ripped holes in the Oldsmobile’s crankcase and fuel tank.

Mexico’s citizens were beginning to take notice of the race. Running commentaries on the radio and in the newspaper featured sensational—and often inaccurate—accounts of the events.

“The newspapers killed us on two successive legs, on two successive days,” complained McGriff.

With highways closed hours before the racers were to pass, spectators brought picnic lunches and lined the road. A crowd of 40,000 gathered a few miles from Durango and witnessed Sterling—now nicknamed “El Vaquero” (The cowboy)—win the leg ahead of Mantz and Deal, who observed publicly, “I didn’t know these guys were going to go so fast!” and privately, to co-driver Sam Cresap, “Let’s get our butts in gear!”

France and Turner, in their 1950 Nash Ambassador, moved up to third overall, with McGriff in fourth. Taruffi finished 19th on the leg and was 23rd overall.

When the third day dawned, 103 cars were ready for the longest grind of the race: 340 miles to Leon, then 278 more to Mexico City. Texan Lonnie Johnson, in a 1949 Cadillac, won leg four, beating out Sterling and Mantz.

Jack McAfee had been plagued with fuel system problems in his 1949 Cadillac since the start and stopped twice on leg four with vapor lock. During the layover between legs four and five, he and co-driver Ford Robinson effected hasty modifications to the reserve tank and set out to make up time. McAfee finished third into Mexico City.

The real hotshot coming into the capital was Deal, who turned in a 93-mph win to move to third for the race. Mantz had started the leg in front of the rotund Deal, who had acquired the moniker of “El Gordito” (the little fat boy), but Deal passed him as they approached the finish line. They came storming into the outskirts of Mexico City with Deal’s Cadillac two car lengths in front of Mantz’ Lincoln. It was exciting to watch, but in reality, Mantz was already eight minutes behind on the leg, even though he had moved into first in the race.

Sterling suffered two blowouts and finished the leg in 16th, dropping to second in the overall standings. McGriff managed to keep his Olds fourth in the race, despite a dismal 14th-place finish on the leg.

“An incident south of Leon slowed us some,” he explained. “A horse was standing on the highway, and a soldier patrolling the course threw a rock at it as we approached, trying to scare it away. The horse fell down! We barely brushed by it at about 90 mph!”

The more favorable hazards of curves and hills allowed the Europeans to improve their standings, as Bonetto and Taruffi finished eleventh and seventeenth on the leg.

After crossing the Mexico City finish line, drivers turned in their route books and Mexican police escorted them to an impound garage in the heart of downtown. No one was prepared for the delirious reception that awaited them on the Paseo de la Reforma, the city’s beautiful central boulevard.

More than one million people crowded the streets for a glimpse of the racers. Fifteen hundred police officers were no match for the crowd, and one driver noted that so far, the toughest leg of the race had been from the finish line to downtown Mexico City.

Mexico’s revenge

Leg six, the 84 miles from Mexico City to Puebla, was the shortest but hardest section for everyone but the natives. Razo Maciel won the leg in his 1949 Packard, followed by Mexico City Packard dealer Jose Estrada Menocal, in an identical car.

“I’ve driven to Puebla so many times that I know every curve without having to look at it—the way you cross your living room in the dark and automatically avoid the chairs you cannot see,” explained Menocal.

McAfee finished third, followed by Mantz, who still held onto the race lead while widening the gap between himself and Sterling, in second-place, to 12.5 minutes.

Mantz may have been in first place overall, but his troubles were only beginning. Feeling ill when he left Mexico City, by the start of the seventh leg in Puebla, he was succumbing to the Mexican malady known as the turista, or the “Mexican two-step,” convinced he’d have to start feeling better before he could die.

Mantz lost his brakes in the mountains and got sick, at the same time. Co-driver Stroppe made a quick repair that allowed the Lincoln to run with front brakes alone, but he couldn’t do much about the driver’s health. After the impromptu pit stop, Stroppe took over the wheel, but in a few miles, Mantz decided that Stroppe’s driving was worse than his own sickness and moved back into the left seat. The two dragged into Oaxaca 69th out of the remaining 75 cars and had dropped from first to ninth in the race.

Bonetto won the leg in his Alfa Romeo and jumped to fourteenth overall. Deal’s Cadillac suffered from a clogged carburetor and stuttered in, in 31st place, still holding onto second place in the race because of Mantz’ bad luck. Deal’s misfortune, in turn, was McGriff’s opportunity; he moved up to third, only 18 seconds behind Deal but 16 minutes back of Sterling, in the lead.

When Stroppe finished working on the Lincoln around midnight, he went to the hotel and found that Mantz had taken a turn for the worse.

“I went looking for a doctor,” he recalled. “The police helped me round up one in a saloon. He took out a hypodermic needle that looked big enough for a horse, and Johnny saw it and fainted dead away. The doctor seemed to know what was wrong with him; the next morning I woke up and looked over at Mantz, expecting to find him dead, and there he was, sitting up and feeling fine!”

Sterling’s bid ended on leg eight when he lost his brakes and plowed into a hillside hard enough to wreck his Cadillac’s suspension. As Sterling limped the car back to Mexico City to await the awards banquet, Royal accused Deal of “paying Sterling more to lose than (Royal) was paying him to win.” He still stubbornly held to that allegation 35 years later.

Leg eight started with 25 miles of straight, level highway, which then turned into 125 miles of mountain roads up to 6,500 feet elevation, before finally descending to 196 miles of hot, flat and rolling country that dipped to near sea level and then roller-coastered back to the finish at a 2,500 feet elevation.

Mantz took off in pursuit of a hopeless cause. He won the leg but was still 28 minutes behind first-place Deal in the race. Tommy Francis came in second on the leg in a 1950 Ford, and Deal third. McGriff was now second overall. Taruffi was ninth and Bonetto 11th.

Truth is more interesting than fiction

Miguel Aleman, president of the Republic of Mexico, presents the trophy and check to winner Hershel McGriff.

If the entire race up to that point had been handed to a Hollywood writer to finish, the created ending wouldn’t have been half as good as the real one.

Only a few stray goats, assorted Indians and a scattering of soldiers standing by the side of the road witnessed what went on between Tuxtla Gutierrez and El Ocotal. Had it been filmed, it would’ve made one of the great racing movies of all time.

The cast of characters included Mantz, who had 160 miles of twisting mountain roads to make up 28 minutes on the leader, and Deal, who just had to hold on and finish in a moderate time to win the race. Turner, with France in their Nash, was so far out of the money that he had to count on a miracle. McGriff was 8:42 out of first place but safely in second and 18 minutes ahead of the Rogers brothers. Taruffi, probably the best mountain driver in the world, was driving plausibly the best mountain car in the world.

The stage was set. Leg nine was so treacherous that the cars were started at four-minute intervals.

Mantz had seen all but the last 90 miles of the Pan-American Highway during his spring scouting trip with Estes. Mantz had heard that the rest of the course was paved with gravel, which would be no problem for the old dirt-tracker.

For half the leg, Mantz and Stroppe roared along in great style, pulling further ahead of the field. Then, below them, they spotted a gleaming white road stretching across a valley.

“Got ‘er made now!” Mantz yelled as they tore ahead. But when they got to the white road, they found that instead of gravel, it was paved with crushed rocks—each the size of a man’s fist.

In a matter of minutes, they had blown all four tires. They changed the tires and proceeded at a slower pace, but soon blew three more. By the time they reached El Ocotal, they had run out of spares and were driving on three tires and one rim, which had wrapped itself around the Lincoln’s brake drum. Thirty-five cars had passed them, and they had dropped to ninth for the race. Their only consolation was about $800 earned in leg prizes.

Meanwhile, Turner and France had found out at the start of leg nine that Roy Pat Conner—whose 1950 Nash Ambassador was in sixth place, 33 minutes out of first—had fallen ill. Being the enterprising fellows that they were, they simply bought Conner’s car—along with sixth place—and drastically improved their odds.

Turner, in the ill-handling, underpowered Nash, with its 115-hp six-cylinder engine, started 20 minutes behind the first car and four minutes behind Taruffi in his nimble Alfa. But Turner had no doubt that he would win.

In the course of the next few hours, he passed the Italian, and everyone else. France related years later that Turner said that when he tried to pass Taruffi on the narrow road, the Alfa driver wouldn’t move over, so Turner just bumped him a few times, Southern style, until he yielded. Then Turner got sidelined with a flat tire, and Taruffi passed him. Turner took off in pursuit, and actually had the Alfa in his sights when they crossed the finish line.

In elapsed time, Turner had beaten Taruffi by 3.5 minutes and Deal by five minutes, to win—almost. A hasty conference of officials revealed that the rules specifically prohibited changing a car’s crew, so Turner was disqualified. To make things worse, his former partner, France, who had kept campaigning their original Nash, ended up wrecking it in the mountains—although not seriously enough that they couldn’t drive it home and campaign it the entire 1950-1951 season on the dirt tracks of the South.

McGriff had set out at Tuxtla to make up the time he needed to beat Deal out of first place. Knowing what the road surface was going to be like, he and Elliott went shopping for some heavy-duty tires.

“We found some six-ply General Popo tires in Tuxtla,” McGriff explained. “The man who sold them to us said that we didn’t have to pay for them if we won the race, so we felt obligated.”

The road on the last 20 miles of leg nine had a high crown in the middle.

“If you kept astride it, it was like being on rails, but if you got to the side of it, you couldn’t control the car,” McGriff related. “Right before the finish, there was a big dip in the road. We hit it going about 100, and the car bottomed out with a crunch. An hour or so after we finished, I went to move the car and found that it was out of gas and had no oil pressure. We had torn huge holes in both the fuel tank and oil pan; we couldn’t have gone another 100 yards after the finish!”

Spoils to the victors

McGriff and Elliott had gone far enough and fast enough to make up almost 10 minutes on Deal and beat him by 1:16 to win the first Carrera Panamericana. The Rogers brothers, who had driven a smooth and careful race in their Cadillac, were in third.

At the awards ceremony in Mexico City, hardware was handed out to nearly everyone and race money awarded to the top three. McGriff pocketed $17,533, Deal $12,022 and the Rogers brothers $5,825, with another $2,700 in leg prizes distributed among 12 contestants.

Race officials decided that the trophy McGriff and Elliott were to receive should instead be awarded to the heroic driver of the “presidential entry”—the one that had crashed repeatedly. Although the move puzzled the Americans, McGriff decided not to complain to his hosts.

“That trophy was solid silver and about five feet tall, with a map of Mexico engraved on it; the race route was traced in emeralds,” McGriff remembered. “The one I got was only about three feet tall, but it was silver, too.”

McGriff’s strategy of driving a conservative race had paid off. He knew that if he couldn’t lead the race, he must stay within striking distance of the leaders and let them set the pace. His leg finishes were high and consistent throughout the race.

“General Motors wasn’t exactly overjoyed that I’d won in one of their products, because they were selling all the cars they could make,” he related. “They said they really didn’t need the publicity. But they did send us on an eight-day tour of eastern U.S. dealers. I raced the Olds the rest of that season without doing much of anything but tuning it up, then I ran the inaugural Darlington race that year.”

Carrera Panamericana, in retrospect, was kind of homey and a little naïve. It was the first great adventure, an excursion into what was to become an ultra-sophisticated specialty of winning in Mexico. Most of the drivers were woefully—if not criminally—inexperienced, the cars weren’t structurally prepared for endurance racing, and the officials were bureaucratic neophytes. But, in spite of itself, the race was a success.

How the Porsche Carrera Earned its Name – Part II